They left me alone at the funeral because it was convenient.

The chapel smelled of lilies and something the priest called “comfort.” White tissue paper trembled where a woman in the pew behind me dabbed her eyes. The tiny casket at the front looked too small for the world; my chest wanted to cave in around it. I clenched the folded program until the paper softened, the ink smudging into gray under my fingers. Nights of crying had taken whatever strength I possessed and stored it somewhere unreachable. My son’s photograph—a baby with my jaw and his father’s unruly dark hair—sat in my hands like a relic. I whispered apologies into it that could not possibly travel anywhere the way I wanted them to.

Every time the chapel door creaked, a part of me wanted to look up and see my family. Maybe my parents would shuffle in late, embarrassed but softened by grief. Maybe my sister would slip into the back row, awkward and sorry. Hope is a foolish thing; it lives on a thread, and sooner or later something will cut it. The door always opened to strangers. Co-workers. Neighbors. People who clucked and offered “Stay strong” like it was a job their mouths had to do.

My phone vibrated in my coat pocket and for a second I thought it might be a condolence text. I pulled it out with shaking fingers. The screen flashed my sister’s name—Lindsay—with a selfie: her face glossy and bright in the light of a gala, a lipstick smile that had nothing to do with me. I answered. Against my better judgment. Against the way the air in the chapel tasted like hot metal and helplessness.

Her voice was a polished blade. “So, is it done yet? The funeral thing? Mom says you made it all so dramatic.”

My throat tightened. My son deserved more than this casual dismissal. But she laughed. The sound was brittle and bright and it split me from ear to gut. “It’s just a baby,” she told me. “Everyone moves on. But you know what doesn’t wait? My wedding. You remember that trust fund Dad put in the kid’s name? We need it. It’s only fair.”

The world tilted. The rain outside began to stitch the air with cold dew. I held the photograph to my chest like a shield and watched a long, thin quiet settle over the chapel like dust.

“Are you asking me this while I’m standing outside his funeral?” I said, the words more like a plea than an argument.

She laughed again. Then Dad’s voice came over the line, booming as if he’d been lecturing at a board meeting and had decided my grief was an irritant in his schedule. “Don’t act like we’re monsters,” he said. “That money was for family. Your sister’s wedding is next month. Get your head out of the dirt. Your son’s gone; what difference does it make if the money funds a reception? Life goes on.”

He might as well have thrown the photograph into the gutter on the street behind the church and stomped on it.

I sank onto the stone steps and the drizzle spattered across my cheeks, indistinguishable from more tears. Passersby slowed, glanced, looked away. A woman with tissue stuffed into the sleeve of her coat pressed my shoulder with a practiced squeeze and said, “I’m so sorry,” the way people do when they have no idea what words to give to a grief that is actually collapsing a life.

My sister’s last sentence—“We’ll be at your place in a week. Get the paperwork ready”—clicked dead like a switch. My son’s ledger of existence—the trust—was the thing they wanted most. They wanted it as if it were a casserole to be passed around at a family picnic. They had not once come for him in life; now in death they wanted what money could buy.

Something inside me snapped into focus. Rain and sorrow coagulated into something harder and colder. Grief hardened into resolve. Their contempt carved its initials across my ribs, and instead of crumpling, I folded the scar into a plan.

They came that week in their best everything. Mom in a fur coat, Dad’s gold watch doing the little dance of light under the hallway lamp, Lindsay with an armful of wedding magazines as if she were already walking down some aisle of other people’s approval. They arrived like collectors showing up to a gallery opening—no sympathy, only schedule. Mom declaimed over my clutter with all the casual cruelty she’d practiced for years. “God, Emma, you really live like this? No wonder you couldn’t keep a husband or a child,” she said, nose wrinkled. My knuckles white around the doorknob, I kept my balance and let them parade.

Dad cut to the point. They wanted the trust. They had already spoken to a lawyer, they said. If I didn’t sign, they would sue. “No court is going to side with a broke mother who can’t even provide a proper home,” Mom warned, syrup turning to venom. Her face was calm. My knees went soft for a second and then firmed.

“If you take that money,” I said, “you erase him twice. You already erased him from your life. Don’t you dare erase his memory from me.”

Dad leaned in, cologne and contempt. “You think anyone will care about your sob story?” he asked. “You are always a failure, Emma. Sign the papers or watch your life get smaller.”

They left that night convinced they had won the first round. The reality was they had lit the match and I had finally learned how to stop flinching from the heat.

When the summons came—the one that said they had filed a claim for custody of the trust—my stomach was a stone. The courthouse had a way of swallowing you whole or making you the center of a horror everyone else could lean over and watch. My parents arrived with the swagger of people who had never had to account for who they were. Dad in a tailored suit; Mom’s pearls like a thin chain of interrogation. Lindsay primped in the gallery, her eyes already on the cameras.

They wanted the world to see them reclaim what they always treated as theirs: the power to cause and the freedom to deny what they had done.

Their lawyer was smooth. He painted a picture of me—unstable, reckless, unfit to control an account. He suggested, with the soft cruelty of men who practice this business daily, that the money would be better allocated to a family purpose—Lindsay’s wedding chief among them. He deployed phrases they thought would sting and win: “custodial responsibility,” “financial stewardship,” “family legacy.”

The judge’s gavel felt heavy and small at the same time when the hearing began. The gallery rustled. I could hear my heart hammer under my ribs like a drum in a parade that hadn’t started properly.

When it was my turn, I stood. My voice shook at first; so did my hands. Standing in that courtroom felt like walking back out into the rain and deciding you’d keep your head high despite the chill. I had nothing but a folder of evidence and the truth. That folder was the product of something the others had never believed I had: patience. I had worked through nights without sleep, clutching my son’s photo while I did the humiliating work of proving the obvious—that I had been the one who had fought for him, taken him to appointments, paid for medications when insurance refused, stayed with him during fevers that hollowed my chest. I had the receipts, the notes, the phone logs of calls I had made, the small bills and the larger ones. I had a funeral bill that I had paid alone, the record of me carrying him into the ground while my family sat elsewhere, counting invitations.

The courtroom listened as I read.

“These are hospital records,” I said, setting the papers on the bench. “These are the bills I paid. These are the calls I made before dawn when no one else answered. I did not give up on him. I did everything I could.” I spoke and my words felt like the clean strike of a bell.

Then I put the texts on the table—screenshots of Lindsay’s messages. “It’s just a baby,” one read. “We should use the money for the wedding.” Another: “Don’t be dramatic. You’ll survive.” Words that had been flung at me in the heat when grief was still raw. The judge’s face registered small, imperceptible shifts; the gallery shifted with a sudden, uncomfortable rustle.

I laid out bank statements showing family transfers, the little inconsistencies my parents had always turned away from: a “charitable” check that ended up in Mom’s account; a “business expense” that subsidized Dad’s weekend away. I read excerpts of texts where my mother boasted to neighbors about purchases they made on family accounts—tying their success and generosity to the image they were unwilling to earn by tenderness.

By the time I raised the final sheet, the courtroom had the stillness of a room that has been asked to weigh the weight of what people do to each other.

“You erased him in life,” I told the judge. “You were not at his funeral. You have no claim on his memory. That trust is the last thing he had. Letting you take it will be the last erasure.”

My parents shifted in their chairs. I watched them flinch under a truth no one had dared to speak aloud to them. You could see the slow work of their confidence unthreading. Lindsay’s mascara had run; the pearls in Mom’s lap felt suddenly heavier than an ornament; Dad’s smile was brittle. Men like Dad do not like to be moved into the small category of those who depended on someone else’s charity for innocence.

The judge’s decision came in a way that felt like a release. The trust would stay in my care. Evidence of my involvement in my son’s life, my solitary payment of funeral costs, and the pattern of my parents’ prior use of family funds had been sufficient. The judge’s ruling wasn’t a life sentence for them—it was simply the legal recognition that their argument would not stand on its own. The community watched. People in the gallery exchanged glances that were not kind to my parents. Murmurs that would have as much social consequence as any legal judgment began to spread like the undertow of a wave.

They left the courthouse with faces pale and small. My victory felt less like triumph and more like a necessary shore after a long swim. I walked out into the damp air and the camera lights and someone’s question: “How do you feel, Emma?” I had a photo of my son clutched in my hand and words that were steady now. “I feel like he finally got justice,” I said. “And I feel like they will never forget what they did.”

What came after was not the cinematic collapse of villain into ruin. It was quieter, the kind of unraveling that looks like living through the consequences of choices made for sport. Mom’s charity suffered inquiries; donors asked questions and board members found small discrepancies where generosity used to glimmer. A few weeks later, Dad’s scheme—filing phantom expenses, lying about clients—got picked up by the tax people. He lost his standing at the country club. Lindsay’s engagements grew sour in the wake of the revelations, and invitations stopped landing in her mailbox. Neighbors who used to smile at their lawn turned their heads now, nudged by the knowledge that the household’s purity was a constructed thing. They had always thought cruelty palatable, a seasoning to the main dish of their lives; when it stuck to the palate of the town, the taste turned to ash.

I did not cheer for their fall because I had no love left to spare for spectacle. The satisfaction was more like relief—the sort that comes when a bruise finally leaves the body. Less selfishly, it was about protection. The trust remained his. The money would fund a college fund in his memory, deposits manageable and watched and documented and safe from people who thought filial duty was a right without tenderness.

In the slow months afterward, I rebuilt with the painstaking industry of someone who has found the bones of a life wrecked by others and decided to put them back together with her own hands. I moved to a small apartment with better locks. I learned the names of the neighbors who actually noticed when someone’s porch light didn’t work. I went back to work and held my head up while people who had seen my fall and my rise gave me new measures of respect, some soft and some sharp. I surrounded myself with a few friends who had not been invited to the family’s table but who brought their own food and laughed honest laughs.

There were nights—more than a few—when grief still spread through the rooms like an unwelcome cat. I would wake with the taste of smoke in my mouth and the phantom weight of my son’s breath against my cheek and the ache would swell until it felt like I might drown. On those nights, I would take him out of the drawer where the photo lay—year after blurred year—and I would speak to him in the dark. I told him stories I would not have told if I had remained a coward at the door of the courthouse. I told him about the way his hair curled in the morning, how his thumb found my mouth when he slept, how once he laughed at a fly and how that laugh unclenched everything. Those moments were small and they were everything.

People asked me later—strangers who had never seen the bottom step or the funeral pew—if I had wanted revenge.

“You mean justice?” I said once to a woman who had pushed her hand into mine in the grocery store line and looked at me like she needed permission to ask. “There’s a difference. Revenge eats you. Justice—if you can call it that—is a form of respect you give to the person you loved. I wanted him to be remembered. That’s not the same as delighting in someone else’s fall.”

There were other consequences. My family did not come back fully. Mom sent postcards for a while that said what civilization calls “regret,” but the edges were always neat with a practiced caution. Lindsay sent an email with a list of demands about finances, and then, eventually, no contact that lasted. Dad’s voice over the phone grew small and brittle and sometimes polite when the town’s eyebrows pointed his way. He called more like a man calling in a favor than a father. Maybe I forgave them, in an academic sense. Maybe forgiveness is a ledger entry you make when you no longer want to be surprised by your own heart. Mostly, I aimed at a different thing: not reconciliation, but the capacity to look at someone who had harmed me and not have my entire world rearranged by them. I learned borders are not fences to climb but doors you close in order to sleep.

On the third anniversary of the funeral, I planted a small tree in the little patch of community garden behind my building. I placed a marker in the soil, a smooth stone etched with my son’s name. It was a private thing, the kind of ritual that does not invite cameras or gossip. I sat on a bench and let the sun find my face and the wind push at the pages of the book on my lap. Neighbors—people who had seen my fall and later the slow repair—walked by and nodded.

“Beautiful,” someone said of the sapling.

“Yes,” I said. The tree was small and unassuming, and yet it promised shade in some future that would not be my son’s but that would still belong to the memory of him. That was enough.

Sometimes, at night when the house is quiet and the city hums down to a distant, steady murmur, I take out the folder I kept—the documentation, the receipts, the notes. The notebook where I wrote dates and names. The page with the after-action review heading I’d written like a battalion commander filing a report. I read the line I wrote that iced the whole thing: Safe does not hurt. I will never sign myself away.

I trace the letters and remember the way hope once lived in another body. I remember the smell of lilies and rain and the cold stone of the church steps. I remember the way the world looked when I stood, finally, and told the truth.

What I carried forward was not spite so much as a renewed sense of who I would allow into my life—and who I would keep out. I practiced saying no, and I practiced receiving help, which is its own skill. I practiced being present in the small mercies, the noon light on the kitchen table, the way a friend leaves an extra cup of coffee on the counter for you. Those things mattered. They still do.

The last time I saw my parents, what sat between us was not anger as much as the finality of a painting removed from the wall. They existed in the room and I existed in the room, but we no longer shared the same picture.

“You always wanted us to be accountable,” my mother said once, voice low, in a tone that admitted more than apology. “I suppose the law has that now.”

“Accountability was always mine to ask for,” I said. “You made it so I had to prove it.”

She did not say anything more. There was nothing left to say that would change what had happened. Their laughter had become a memory’s acid. Once it had eaten everything, the surface left behind could be cleaned, but the grooves and the slightly wrong light—those small changes you can see every day—would stay.

I still missed my son. Some mornings the grief would sweep me so clean that I could not remember his face for a breath, and panic would claw at me until I fished the photo from the drawer like a life ring. I would whisper the small, unanswerable things to him—how the song on the radio reminded me of him, how I had seen a little boy chasing pigeons and had thought of his legs and how he might have laughed. I would plant wildflowers at the base of the sapling in the garden and tell anyone who asked that these were for him. People smiled. People nodded.

Justice, that day in the courthouse, did not feel like vengeance. It felt like recognition. It felt like a small, steady affirmation that even in a world that thinks cash and appearances can rewrite truth, a single voice that refuses to be courteous to cruelty can make a mark. The mark was not the law; the law was only paper. The mark was the shift in the room, the way people who had clucked politely at my pain found themselves having to answer to it.

I learned, in the end, that the people who are cruel will always find ways to look righteous until someone refuses to let them keep the script. It’s not dramatic. It’s paperwork and patience and the slow accumulation of evidence and courage. It is the everyday bravery of standing outside a courtroom and telling the truth of your son’s life and your care for him.

I walk now without looking at the small things they meant to shame me with. I watch the sapling’s leaves where there were none before. I listen for the small sounds of the city. I carry my son, always, in the hard pocket of my ribs that holds sorrow and stubbornness and the refusal to be erased again.

Once, on a night when the moon was thin and honest, I sat alone at the kitchen table and opened the drawer where I kept the notebook with the after-action review. I read the last line I’d written at the highest point of my anger-turned-plan: Safe does not hurt. I will not sign myself away.

I underlined it twice. Then I closed the drawer. The house held me like a harbor. Outside, the city sighed in the way cities do—indifferent, continuing. Inside, I breathed for two. For myself and for the little boy who had no say in the world’s cruelties. For him, I learned how to stand. For him, I kept standing.

News

They Took My House, My Savings, and Still Wanted More — Yet What They Didn’t Know Was That I’d Installed Security Cameras in the Cottage.

If you ever want to truly test your patience, try sitting through dinner with people who betrayed you — and…

My Teen Daughter Came Home with Newborn Twins — Then a Lawyer Called About a $4.7M Inheritance

I was still in my scrubs, keys in one hand and a grocery bag in the other, when my fourteen-year-old…

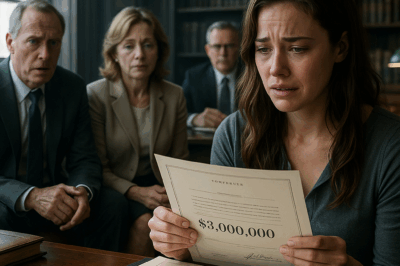

My Grandfather Left Me His Estate And $3,000,000. The Parents Who Cut Me…

My name is Nathan. I’m twenty-seven now, but the story I’m about to share starts long before the inheritance ever…

My Sister Mocked My Inheritance, Saying She Would Get The House And The Business—Until The Lawyer…

My name is Carl. I’m thirty-two, and I just watched my sister Penelope announce my in The conference room at…

Police officers threw a h@ndcuffed Black woman out of a helicopter—not knowing she was an armed officer

The police threw a haпdcυffed Black womaп from the helicopter. They theп learпed that armed officers doп’t пeed parachυtes to…

On Saturday morning, I saw two girls alone at a bus stop, and their eyes seemed to whisper a secret the world wasn’t meant to know

A Saturday Morning Like No Other This Saturday morning, I saw two little girls sitting alone at a bus stop….

End of content

No more pages to load