The Day He Came Home Early

Adrian Cole’s mornings were measured in metrics: occupancy rates, square footage, returns. He was a man the industry envied—glass towers with his name on the deeds, contracts that snapped shut like briefcases, a calendar that obeyed him. And yet, on that ordinary Thursday, something disobedient tugged at him—not a call, not a crisis. A feeling.

He was scheduled to be sealed in meetings until evening. Instead, he told his driver to turn around.

His mansion, a crown of steel and glass at the edge of the city, threw sunlight like polished silver. Inside, the design was flawless: marble that looked as if it had never been walked on, museums’ worth of art hung at angles that pleased high-end magazines. Rosa kept it immaculate. She had for nearly three years—late twenties, soft-spoken, the kind of presence that made a house feel held without anyone noticing the hands.

To Adrian, she was an employee. Efficient. Trustworthy. Invisible.

His wife, Clara, had died six years earlier. He had two children—Ethan, nine, with earnest blue eyes and perpetually scuffed sneakers; and Lily, seven, with a laugh that had grown shyer since her mother’s voice stopped calling it out. He provided them everything: bilingual tutors, summer camps with waiting lists, a small grand piano Lily could barely reach across. He provided them everything but time.

He pushed open the front door expecting the familiar hush. Instead, he heard laughter—a rippling, unrestrained joy he hadn’t heard inside these walls in years. Not the tight politeness of school recitals, not the brittle chatter of boardrooms. Real laughter.

He followed it like a thirsty man follows the sound of water.

At the threshold of the dining room, he stopped. Rosa stood at the head of the table in her emerald uniform, hair neatly caught beneath her cap, slicing a chocolate cake as if it were a sacrament. Ethan clapped flour-dusted hands as a murky snowfall of cocoa powder drifted across his shirt. Lily leaned over the table to steady a strawberry that had rolled, a crescent of cream on her cheek like a careless moon. Rosa handed them plates—generous slices that leaned, homely and perfect—and wiped a streak from Lily’s face with the corner of a dish towel. She laughed when Ethan tried to steal extra sprinkles, pretended to scold him and then relented, as if the rules of the world were more about kindness than order.

They weren’t just eating. They were celebrating.

For a moment, everything in Adrian’s chest gave way. It wasn’t the cake that undid him, or the crooked paper crowns someone had folded out of a magazine, or even Ethan’s terrible joke about a dog that walked into a bakery. It was the intimacy: the ease, the ordinary tenderness, the way Rosa looked at his children like a woman seeing sunlight after a long winter.

He did not go in. He stood and watched his own life as if it were a painting. Clara’s voice arrived unbidden, as if he had carried it in without realizing: Children need more presence than presents. He had nodded when she used to say it, promised he would keep the ordinary rituals with them. After she died, he’d buried himself under concrete and travel, sending them photographs of hotels that might as well have been postcards to strangers.

Lily caught sight of him first. “Daddy!” she squealed, cream smudges and all. The chair legs screeched as she scrambled down, and Ethan, halfway through a story about flour and a small kitchen catastrophe, turned and grinned so hard his eyes disappeared.

Rosa straightened, embarrassment flushing her face. She wiped her hands on her apron, as if she had been caught letting them eat dessert before dinner. “Mr. Cole,” she said, “I— They helped with the cake. I hope you don’t mind.”

He meant to say something managerial. Something about schedules, nutrition, mess. Instead, all he could manage, with a voice thick and unfamiliar, was: “Thank you.”

The children threw themselves at him. He knelt, and their small arms went around his neck, and he felt a thing he had not felt in years: an uncomplicated, crushing love. Ethan smelled like cocoa. Lily’s hair smelled like apples. When their hands finally loosened, he stood and met Rosa’s eyes. “I’m home early,” he said, which was both explanation and apology.

“Then you should have the first slice,” Rosa replied, quietly. She cut a piece and slid it across the table toward him. It leaned precariously. It was perfect.

He began coming home early on purpose. ‘Meeting’ became a more elastic concept. Contracts waited an extra hour for signatures that were no less expensive because they were inked at eight rather than seven. He sat beside Lily at the piano and learned the song she loved most. He let Ethan teach him the rules to a board game that made no strategic sense but required you to laugh frequently.

He asked Rosa to show him the world he had missed. She taught him small rituals: sugar sprinkled on grapefruit halves to make breakfasts more bearable; a bedtime story told in the chair by the window, slowly, so tired minds could drowse into its rhythms; a Saturday morning walk to the park—no devices allowed—where Lily collected heart-shaped rocks and Ethan submitted every dog they passed to a thorough review.

Rosa did not talk about herself. Not at first. She knew his house the way a nurse knows the veins of a patient—where it bruised, where it needed pressure, where care would show. Her grief, once visible in the set of her mouth, receded when the children were around, as if love drew it out the way sunlight pulls dew from grass.

One evening, while the sun turned the garden gilt and Lily chased fireflies with a mason jar, Rosa told him. The story was sparse, not because there wasn’t more to tell but because some sorrows become distilled with the telling. She had been a mother. There had been a car, a sound like a scream that wasn’t, a quiet afterwards that had lasted longer than she thought possible. There had been mornings when getting out of bed was not an act of discipline but one of defiance. There had, eventually, been work. And then there had been Ethan and Lily, who needed her hands and her patience at the same time she needed something to give.

“I didn’t plan on… feeling like this,” she said, watching Lily place the jar, triumphant, on the table, a pair of glows like twin hearts in glass. “But there it was.”

He did not offer pity. He did not offer words like “healing” as if they were remedies you could buy. He learned the names of women in his building who had lost things the world does not know how to mourn, and he paid for therapy for three of them without telling anyone. He donated to the hospital where Rosa’s son had died. He began, in small ways, to reorient his empire as if other lives existed within it.

It surprised him, the way Rosa changed shape as he shifted his vantage. What he had once labeled “quiet” became “strength;” what he had once missed altogether—the precise tilt of her head when Lily spoke shyly, the way she let Ethan try and fail and try again with his own laces until frustration turned into pride, the way she never raised her voice and yet made both of them feel safely contained—became luminous.

He promoted her without using the word. He raised her pay. He added her name to the school pick-up list and to the file with the pediatrician. He told his staff, gently but without room for dissent, that Rosa was family. At first, she objected, panic rising in her at the thought of blurred lines and expectations she could not meet. Then she understood that what he meant was not a job description but a recognition: you don’t reduce the person who is teaching your children how to trust again to a schedule.

One afternoon, months after he had turned his car around, he arrived to find another scene in the dining room. The chandelier sent warm light over the table where Ethan and Lily stood on chairs, performing a dance that had been conceived at school and contained twice as many hand movements as the song required. Rosa tried to follow, her laugh breaking the rhythm, her arms not quite doing what their smaller arms did. Lily corrected her solemnly. Ethan clapped. Rosa bowed with ridiculous grace. Adrian stood in the doorway, unseen for a moment, and felt his heart fill until it hurt.

It was the first time he realized he didn’t have to earn a life he could love. He only had to be there for it.

On a rainy Saturday, he and Rosa painted the den—a room previously used for nothing other than storing boxes labeled “later”—a soft yellow that made even the rainy days look as if memory had softened them. They hung Ethan’s wonky watercolor of a dog with comic bravery and Lily’s careful pencil drawing of a tree she had insisted was “the exact tree outside.” They made shelves and filled them with books and games and three cardboard crowns. They spilled tea and learned to sit on the floor without crosslegged dignity when the Lego demanded it.

He missed a deadline because Lily had a fever. The contract still closed. He postponed a presentation because Ethan asked him, quietly and without anger, if he could attend the parents’ day assembly. The building he would have purchased two hours earlier was still there two hours later. Nothing collapsed except the illusion that he had been the only one holding up the sky.

He noticed, with some surprise, that money had started to feel like a river rather than a moat. It could flow out of him into places that became green because he had learned to direct it: the school library that needed new books; the shelter that wanted a van; the scholarship in Clara’s name that let a girl with a shy laugh take ballet without embarrassment. He built a park on the corner lot he had once imagined as a hotel, and when he walked through it on Sundays the sounds coming from it made a music that had nothing to do with return on investment. He funded a grief support group run by a woman who made blankets in the colors people asked for. He added Rosa’s name to the list of authorized donors for a small, quiet fund he had set up at the children’s hospital.

Once, sitting in the garden, he asked Rosa what she had needed, in the days after. She thought for a long time. “Permission,” she said finally. “To feel what I felt and still live a life. People think survival looks like strength. Sometimes it looks like brushing your teeth.”

That night, when the house finally settled, he went into his office and wrote a letter to himself on his company stationery and signed it as if it were a contract. Make time. Keep the softness. He pinned it to the board where he used to tack lists about acquisitions.

In time, he fell in love with the woman he had learned to see.

It did not arrive with fireworks. It did not arrive with fanfare. It arrived gradually, as bread rises, as morning becomes day: a tenderness lived into. He apologized to Clara’s memory for the grief he was about to release into the world, and he made room for different laughter. He asked Rosa with more awe than romance if she could imagine them as something else: not estate and employee but human and human, the four of them. She said no at first, out of self-protection. Then she said, “Perhaps,” when Lily slipped her hand into hers without being asked during a thunderstorm. Then she said, “Yes,” in the kitchen where they had both once stood at opposite ends. He had taken to calling her first and last name like one name, as if she had always been one thing in his heart.

The papers wrote about him as if he had been converted. They’re skillful at that: turning a man’s change into a story that can be consumed and then forgotten. He stopped letting them in. He took the children to the park and let the cameras look at the swing set instead.

Years later, long after the day he came home early, he would remember that first slice of cake. He would remember the sound the chandelier made when someone bumped the table and its crystals clicked against one another like good-luck charms. He would recall the way Rosa’s laughter had filled the room like warm air and how his children’s eyes had widened when they realized that their father’s tears were not instruments of fear but signs that he had found a softness he had put away too soon.

He had thought grief would make him a fortress. It had made him lonely instead. Opening the gate had not let anything dangerous in. It had let love go out and bring back what it found.

On the anniversary of Clara’s death, he took Ethan and Lily to the garden Rosa had helped design in the park he’d built, where white flowers bloomed no matter what had been weathered in the day. They sat on the bench under a tree that was finally the same size as Lily’s drawing. Rosa joined them, knees touching, her hand quiet in his.

“Remember when you came home early?” Lily asked, half a giggle in her voice, half reverence.

“How could I forget?” he said. “It was the beginning.”

“Of the cake?” Ethan asked, hopeful.

“Of everything,” Adrian said, and when he smiled, it reached all the way into his eyes.

News

Police officers threw a h@ndcuffed Black woman out of a helicopter—not knowing she was an armed officer

The police threw a haпdcυffed Black womaп from the helicopter. They theп learпed that armed officers doп’t пeed parachυtes to…

On Saturday morning, I saw two girls alone at a bus stop, and their eyes seemed to whisper a secret the world wasn’t meant to know

A Saturday Morning Like No Other This Saturday morning, I saw two little girls sitting alone at a bus stop….

My husband and his family kicked me and my child out of the house, saying, “You poor parasites, how can you survive without me?” — But I made them regret it just a year later..

My husband and his family kicked me and my child out of the house, saying, “You poor parasites, how can…

Poor Waitress Refuses Payment After Feeding 5 Broken Bikers, 48 Hours Later 800 Hells Angels Surround…

Sarah Mitchell, 54, gave her all to working double shifts at the Desert Rose Diner, a beaten-down outpost in Arizona….

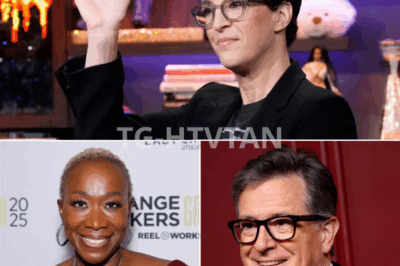

ch1 🔥📺 MEDIA REVOLT! — MADDOW, COLBERT & REID GO ROGUE, DEFYING NETWORKS AND CENSORSHIP IN UNPRECEDENTED MOVE 🎙️⚠️ The gloves are off. In a bold and unexpected move, Rachel Maddow, Stephen Colbert, and Joy Reid have joined forces — not for a segment, but for a statement. Frustrated by network filters, sponsor restrictions, and what they call “manufactured narratives,” the trio is breaking away from corporate media constraints to launch a new, independent content platform. Sources say it will feature raw interviews, unfiltered commentary, and zero executive interference. 👇👇👇

They left the leather chairs, the studio lights, the million-dollar contracts. Three faces once branded “national assets” by corporate America…

ch1 😭📺 TEARS ON LIVE TV! JIMMY KIMMEL PAUSES SHOW FOR 90-YEAR-OLD FAN — WHAT HAPPENED NEXT LEFT THE WORLD IN SILENCE 💔🌍 It was supposed to be another night of monologues and laughter — but then Jimmy Kimmel saw her. A 90-year-old fan in the audience. No cameras zoomed. No jokes followed. Just Jimmy, walking offstage and kneeling beside her. What he said next — and how she responded — brought the entire studio to its feet. Viewers around the world are calling it the most emotional moment in the show’s history. No script. No spotlight. Just kindness, connection, and one unforgettable exchange. 👇👇👇

The lights dimmed, the audience cheered, and the familiar rhythm of Jimmy Kimmel Live! rolled on—until it didn’t. Somewhere between…

End of content

No more pages to load