SHE MURDERED 52 NAZIS WITH A HOLLOW BIBLE – THE DEADLIEST NUN IN WW2

Part I — The Vows That Broke

A hollow Bible sits on a wooden table—its pages carved away with meticulous patience, edges smoothed, glue blended so carefully that no soldier with even the sharpest suspicion could notice. Inside the cavity rests a German Luger pistol and three glass vials, each clearer than water but deadlier than any bullet. No Nazi officer ever searched these pages. No German ever imagined that this sacred object concealed the instrument of their quiet destruction.

Belgium, 1943.

In a war defined by tanks, bombers, invasions, and mass graves, one nun—one woman in plain black cloth—eliminated more German command than an entire battalion. Her name would never appear in official archives. Her actions would be debated for decades. And her story, obscured by myth and fragments, became one of the most morally complicated acts of resistance in the European theater.

Her name, before the war reshaped her destiny, was Sister Alexandra.

But the world would remember her differently.

Some would call her a savior.

Some would call her an assassin.

Some would call her a contradiction of faith and violence.

History would eventually settle on a single phrase whispered among resistance testimonies:

“The Nun with the Hollow Bible.”

October 1938 — Louvain, Belgium

It began not with violence, but with silence.

Sister Alexandra stood alone in the monastery library at dawn, her hands brushing the spines of leather-bound volumes collected over three centuries. The Benedictine monastery held nearly five thousand works—scripture, medieval medical texts, naturalist treatises, illuminated manuscripts that glowed when the morning sun touched their gold leaf. Every book was a world; every binding a prayer made physical.

Her fingers paused on one particular margin—a faint pencil mark from sixteen years earlier. Her younger brother’s handwriting. Clumsy, uneven, written when he was no more than twelve. He had visited the monastery as a boy, running between the shelves, asking questions she could scarcely answer then. He had traced the letters of Latin titles with his fingertip, dreaming of becoming a priest, a scholar, a servant of something greater.

Six months later, he would be executed.

The Germans would arrive in Belgium with an obsession for documentation and punishment. They would interrogate priests, pressure parishes, demand collaboration. Her brother refused. A refusal in those days was not simply disobedience—it was a death sentence.

As Sister Alexandra stood in the morning light, the memory of him became inseparable from the rows of books around her. She traced his old annotation with trembling fingers, and a clarity—not divine, but deeply human—rose within her.

Vows made in peace did not apply in the presence of evil.

The monastery bells rang six times. Somewhere beyond the walls, German boots marched on stone streets. Families listened from behind shutters. Priests whispered hurried warnings. No place in Belgium would remain untouched.

The world was changing. And she, cloistered in vows of silence, obedience, and nonviolence, realized that the greatest violence would be to do nothing.

The Hollow Bible

The decision was not dramatic. It came upon her like breath, undeniable and immediate.

She selected the oldest Bible in the library—a seventeenth-century edition bound in cracked leather. Its spine had loosened from centuries of use; its pages softened by prayers and age. To choose such a volume was itself a crime of sacrilege, but crimes were becoming an unavoidable reality.

She carried it to her cell: a narrow room with a wooden desk, a straw mattress, and a crucifix that seemed to watch her with silent judgment. If she hesitated, even for a moment, she would not begin at all. So she opened the Bible and, with a monk’s practiced precision, began cutting.

Page by page.

Layer by layer.

Hour by hour.

Her hands never shook. A lifetime spent illuminating manuscripts—mixing pigments, restoring antique pages—had trained her for this. She carved a rectangular cavity three inches deep, four inches across, and six inches long.

When finished, she lined the hollow with a paste derived from medieval conservation manuals stored in the monastery vaults. She pressed the remaining pages until they sat flush, indistinguishable from untouched scripture. When she closed the cover, the Bible looked no different than it had that morning. Only she knew the truth—words had been removed to make space for the tools of killing.

She placed three things inside the cavity:

A photograph of her brother, taken before the occupation—a young priest with hopeful eyes.

Three vials: strychnine, cyanide, and a fungal neurotoxin refined by a French chemist hiding in the monastery basement.

A folded sheet of notes—names of German officers, their schedules, their routines.

There was no weapon yet. Not in the conventional sense.

The Bible itself was the weapon.

When she closed it, the faintest whisper of air moved between the pages, and she felt—as she would later describe in her private writing—that she had “closed the door on the woman I had been.”

The Shadow Ministry

The resistance in Belgium did not arise from army remnants or foreign influence. It grew from within: from teachers, doctors, priests, farmers, and women whose grief had turned to resolve.

In the basement of a house in the Jewish quarter, Sister Alexandra presented the hollow Bible to a small cell known only as The Shadow Ministry.

No greetings.

No oaths.

No ceremony.

She placed the Bible on the table. Four figures watched: a printer, a forger, a weapons smuggler, and a man whose identity was so sensitive that no one ever spoke his name aloud.

“Target?” the scarred man asked.

“Four,” she said softly.

Four German officers responsible for four separate atrocities. Four deaths that would seem natural. Four holes in the Nazi command.

Those four deaths would be only the beginning.

But she could not return to her old name. She needed a new self—one the Germans would overlook.

Thus Sister Maria was born. A name bland and harmless. A name designed to disappear.

May 10, 1940 — The Occupation Arrives

The Germans entered Louvain with 500 soldiers and armored vehicles, the thunder of metal against stone echoing across the medieval city. The Wehrmacht’s Sixth Army moved with frightening precision, using Belgium as a stepping stone toward France. Resistance was futile; Belgium fell in eighteen days.

Colonel Otto Lang—a veteran of the Polish occupation—claimed the monastery as his headquarters. He was meticulous, cold, and ambitious. The library, containing over 100,000 volumes, fascinated him not for its beauty but for its ideological value. Berlin believed medieval manuscripts could be weaponized to “prove” Aryan supremacy. Lang had orders to preserve the library for propaganda research.

Ironically, his presence—intended to safeguard the collection—would enable the woman who would later kill him.

Thirty German officers moved into the dormitories. Soldiers patrolled the cloisters. The abbott’s study became Lang’s office. The monastery—the most peaceful place Sister Maria had ever known—became the beating heart of Nazi control in the region.

Yet to the occupiers, a nun moving silently through hallways, carrying soup or linens or scripture, belonged so thoroughly to the background that she ceased to exist in their perception.

She became invisible.

And invisibility was her camouflage.

The First Kill

The first officer to die under her hand was Hauptsturmführer Ernst Becker, known for personally overseeing the arrest and execution of dozens of Belgians.

His death came on June 14, 1940.

No drama. No confrontation. No suspicion.

He consumed the communion wafer she had prepared—a wafer dusted with a microdose of a neurotoxin that mimicked the onset of cardiac failure. His death was recorded as “massive coronary event.” His body was shipped home with honors. His family never questioned the funeral.

Three weeks later, another officer died.

And then another.

And another.

Over the next four years, 41 German officers stationed in or around Louvain died quietly.

But the deaths were spread across years, locations, and units. Nothing connected them—except her.

To the Germans, they appeared as fate, stress, illness, or unfortunate coincidence.

To the resistance, they were strategy.

The Mathematics of Disruption

Sister Maria never aimed for numbers. She aimed for impact.

Each officer she eliminated forced the German command to reshuffle. A raid delayed. A deportation postponed. A planned execution rescheduled until the prisoners escaped. Every “natural death” disrupted operations for days or weeks.

In occupied Europe, the deadliest weapon was not a gun.

It was delay.

Delay saved lives.

Delay confused command.

Delay weakened the occupation.

By 1941, her actions had saved hundreds—if not thousands—of civilians, though she would never know their names.

But the silence that protected her would not last forever.

August 16, 1941 — The Photograph

She was summoned to Colonel Lang’s office.

Her blood chilled.

Six days earlier she had killed Major Wilhelm Hoffman. She expected arrest, interrogation, perhaps execution. Instead, Lang showed her a photograph: her speaking with a wanted resistance operative in Brussels.

“Do you know this man?” Lang asked.

“No, Colonel.”

Her voice did not tremble. Her pulse did not betray her.

Lang studied her with an unreadable expression.

“My officers believe you are resistance,” he said. “They have prepared a warrant.”

Her hand touched her crucifix—not for prayer, but for reassurance. Inside her own mouth, fixed behind a false tooth, a cyanide capsule rested. A plan for a quick death if ever captured.

But the guards did not enter.

Lang did not call for an arrest.

He closed the photograph in his drawer and spoke quietly:

“If you were resistance,” he said, “you would have killed me by now.”

Then he dismissed her.

He had asked the question not to expose her but to allow her to deny it. He wanted to believe her innocence—perhaps to avoid confronting the monstrous reality that a nun had outwitted his entire command.

That moment—his humanity or weakness—would save her life.

It would also doom him.

Part II — The Doctor Who Saw Too Much

In the months that followed Colonel Otto Lang’s unsettling display of selective blindness, Sister Maria operated with renewed caution. She had crossed an invisible threshold: the occupiers were not entirely oblivious. Some, like Lang, suspected but chose to look away; others, she feared, might not be so inclined.

The monastery breathed under a strange tension—German boots on old stone floors, radios crackling with coded transmissions, and beneath it all, the quiet rhythm of monastic life that persisted stubbornly through occupation. Psalms continued at dawn. Bells continued to ring. The gardens continued to grow herbs—some healing, some deadly.

It was in one of these gardens that the next shift in her war began.

The Arrival of Dr. Friedrich Gruber

In March 1942, a new figure entered the monastery: Standartenführer Friedrich Gruber, a 39-year-old medical officer of the Wehrmacht. He had a reputation for brilliance and for meticulous, almost obsessive attention to medical detail. Unlike other officers, he did not drink heavily, did not indulge in the comforts of occupation, and asked far more questions than was comfortable.

His job seemed simple: conduct a medical inspection of the facility, examine records, ensure no epidemics threatened German forces.

But his true purpose revealed itself the moment he stepped into the dispensary where Sister Maria worked.

“Tell me about Major Hoffmann,” he said without greeting.

She looked up from the shelf where she arranged herbal tinctures. “Major Hoffmann became ill in August. I provided comfort measures. He was transferred to Brussels. He died there.”

“Of pneumonia,” Gruber replied, flipping through his file. “Sudden onset. Aggressive. Four days from admission to death.”

“Yes.”

“And before that,” he continued, “Hauptsturmführer Becker. Heart failure.”

Her silence was steady.

Gruber stepped closer. His eyes—calm, sharp, trained to diagnose what others could not see—moved over her face, her hands, her posture.

“I have reviewed these deaths carefully,” he said.

“And I have found something interesting.”

She waited.

“I believe,” Gruber said softly, “that someone is killing German officers stationed in this monastery.”

Not an accusation. A statement of fact.

“And I believe,” he added, “that whoever is doing it is highly skilled.”

Still she did not speak. She allowed her breathing to remain slow, her eyes steady, her hands calm.

Gruber continued, “The deaths are natural in every clinical indicator. The pathophysiology matches textbook cases. The symptoms mirror biological failure. Yet the timing, Sister… the timing is too precise. Too consistent. Too purposeful.”

He placed the file on the table.

“Whoever is responsible is not merely killing. They are controlling the narrative of biology itself.”

He stepped back.

“For months, I have monitored the reports from this monastery. I requested this assignment specifically.”

His voice dropped to a whisper.

“I came to find the person who understands death as well as I do.”

Her hand grazed the tooth in her mouth—the cyanide capsule. If she bit down, her story would end here.

But then Gruber reached into his coat and removed something that changed everything:

A letter.

Handwritten. German. Dated March 12, 1942.

“To the one conducting these eliminations,” it began.

“I am a physician. I recognize your craft.”

He set the letter between them.

“I know what you have done,” Gruber said. “And I know why.”

The Offer

Gruber folded his hands behind his back.

“If I wished, I could have you detained within the hour. Interrogated. Tortured. You would be dead by nightfall.”

Her pulse did not change.

“But I will not do that,” he continued. “Because I no longer believe in the Reich I serve. I have treated men whose cruelty I cannot comprehend. I have watched what we have done in Poland. In Russia. To civilians. To children.”

He looked not at her, but at the bottles of herbs behind her.

“I cannot fight the Reich with guns or conspiracies. But I can choose which truths I report. And which I do not.”

He held out the letter.

“This is my permission,” he said. “Not my protection. Do not mistake the two.”

She did not reach for the letter.

“If you are caught,” he said, “I will deny everything. I will claim this is forged. I will assist in your execution. I cannot publicly betray my uniform.”

He met her eyes.

“But privately, I will keep the path open for your work. I will ensure no investigator examines the bodies too closely. I will ensure autopsies remain shallow. I will ensure Berlin sees coincidence, not pattern.”

The dispensary fell silent.

“For the next few months,” Gruber said finally, “you may operate with less fear. Not none,” he added. “Fear is your ally. But less.”

Sister Maria understood, in that instant, that she was looking at a man who had crossed his own moral threshold. He had not chosen resistance. He had chosen complicity with resistance.

She picked up the letter.

Then, slowly, she put it in her mouth, chewed, and swallowed it.

Gruber watched without expression.

“Very well,” he said. “Then our conversation never happened.”

He left the dispensary.

From that day forward, no autopsy in Louvain ever penetrated deeply enough to reveal the truth.

Perfecting the Craft

By mid-1942, Sister Maria’s operations evolved from necessity into precision. She was no longer simply poisoning; she was shaping death.

The French chemist hidden in the monastery basement continued to refine compounds—alkaloids, fungal toxins, cardiac disruptors—all derived from plants grown in the monastery’s herb garden. Brother Lucien, the elderly monk who tended the manuscripts, provided her with ancient treatises on herbal medicine used since medieval times. She combined this ancient knowledge with modern chemistry.

Death, she learned, was a sequence.

A choreography.

If the sequence was followed, death looked natural.

If the sequence was broken, it looked like murder.

She studied:

• Cardiac collapse

• Cerebral hemorrhage

• Allergic anaphylaxis

• Septic shock

• Neurotoxic paralysis

She memorized how each ailment unfolded from within.

Which symptoms arrived first.

Which organs failed last.

Which signs doctors searched for—and which they overlooked.

She learned to trigger strokes that resembled hypertension.

She learned to mimic heart failure in men whose stress made it believable.

She learned how to cause respiratory collapse that looked like influenza.

A week of microdoses.

A final dose.

A silent death.

Four hours of medical confusion.

A signature on a certificate.

A coffin.

War, she had learned, was not always fought with guns.

Sometimes it was fought with knowledge.

The Death Toll Rises

Between June 1940 and August 1944, 41 German officers died in or around Louvain under her hand. These deaths were spread thinly enough that Berlin never connected them.

The causes written on their death certificates included:

• myocardial infarction

• cerebral stroke

• pneumonia

• sudden febrile infection

• allergic shock

• complications of ulcers

All tragic.

All medically plausible.

All false.

Each death bought time.

Each time bought lives.

A planned deportation of Jewish families was postponed when the two officers organizing it died within days of each other. Their files were not in order. Their successors did not know the details. By the time new orders were issued, the families had vanished into the countryside.

A planned execution of partisans was delayed when the commanding officer suffered a stroke. His replacement postponed the operation, unsure of the protocols. The prisoners escaped with outside help.

A planned raid on a resistance hideout never occurred; the officer who commanded it died days before it was scheduled.

The Germans never realized they were fighting an enemy within their own headquarters.

To them, these were unfortunate coincidences in wartime.

To the resistance, they were victories.

The Gestapo Arrives

In July 1943, the first real threat to her anonymity emerged.

Six Gestapo officers arrived at the monastery. They were led by Sturmbannführer Klaus Müller, a specialist in interrogation—not the brutal kind practiced by common thugs, but the psychological variety that broke the mind before the body.

He had come for a single man:

Michel Verdier, a high-ranking operative in the resistance.

Someone had betrayed Verdier. The network scrambled, evacuated the hidden chambers, burned documents, and moved people out in hours. The monastery appeared clean.

But Müller suspected more than Verdier.

He suspected a pattern.

On his third day, he summoned Sister Maria.

Müller’s Interrogation

She entered the abbott’s study—now the heart of German authority—with composed steps. Müller sat behind the desk, his scarred face like a carved line across stone.

“Sit,” he ordered.

She obeyed.

He studied her for a long, uncomfortable moment before speaking.

“You have been here since before the occupation.”

“Yes.”

“You have access to the officers. Proximity. Privacy. Opportunity.”

“Yes.”

“You have been present,” he continued, “in nearly every instance in which an officer fell ill before death.”

She did not respond.

Müller smiled—not kindly, but knowingly.

“All evidence suggests you are the assassin.”

She folded her hands in her lap.

“Then arrest me.”

Müller leaned forward.

“I cannot.”

She looked up.

“If I arrest you,” he said, “and if you are innocent, the church will use you as a symbol. A martyr. Propaganda. I will lose more than I gain.”

“And if I am guilty?” she asked quietly.

“Then arresting you would inspire others. A thousand others. Women. Nurses. Clergy.”

He tapped the desk with two fingers.

“No. If you are guilty, I cannot expose you either.”

He stood.

“You are being transferred,” he said. “To Brussels. As a civilian nurse. Your papers are forged. Your assignment begins tomorrow.”

She understood.

He was removing her from his jurisdiction not as justice, but as strategy.

“Disappear,” Müller said. “Before someone less reasonable begins asking the same questions.”

As she left the office, he added:

“In another world, Sister Maria… you and I might have been on the same side.”

She did not look back.

Part III — The Mobile Assassin

The monastery that had been Sister Maria’s sanctuary, her crucible, and her battlefield was now behind her. Brussels awaited—a city woven with tension, surveillance, and a wariness that seeped into every café and alleyway. While the monastery had offered the illusion of cloistered walls, Brussels was open, sprawling, and far more dangerous.

Yet for her mission, it was perfect.

Her forged documents identified her as Sœur Marie-Claire, a civilian nurse from a monastery in Charleroi that had supposedly been bombed during an Allied airstrike. The story elicited immediate sympathy and zero questioning. War produced lies that resembled truth so closely that people rarely probed them deeply.

Her new place of work, Saint-Remy Hospital, was one of the largest medical facilities in German-controlled Belgium. Officers came through daily—wounded, sick, drunk, exhausted. Soldiers wandered the hallways. Gestapo agents came for examinations. SS commanders visited for the smallest cough.

Where there was illness, there was opportunity.

And where there were officers, there were targets.

The Hospital as a Hunting Ground

Saint-Remy had been gradually militarized since 1941. Wards were converted to German-exclusive sections. Civilian patients were relegated to older wings. The basement held medical stores that the Germans commandeered regularly. Yet in all of this chaos, the most invisible figures remained the nurses.

They were shadows in white.

Everywhere and nowhere.

Trusted and ignored in equal measure.

Sister Maria adapted immediately.

She learned the shift rotations of German medical officers.

She discovered which doctors were loyal to the Reich and which resented it quietly.

She catalogued which officers visited the hospital regularly and which arrived unannounced.

By her sixth day, she had identified seven potential targets.

By her twelfth, she had identified twenty-three.

The Shadow Ministry provided the final verdict: out of these twenty-three, four were deemed responsible for direct atrocities. These were her assignments.

Not every German officer was a target—she refused to kill indiscriminately. War had already soaked the continent in enough blood. Her killings were not vengeance; they were surgical.

Calculated.

Selective.

Necessary.

The First Death in Brussels

The first officer she eliminated in Brussels was Hauptfeldwebel Reinhardt Vogel, 42 years old, responsible for supervising deportation transports from Antwerp to Mechelen. From Mechelen, the trains went east—to camps whose names she did not yet know, but whose final purpose she understood too well.

Vogel visited Saint-Remy complaining of severe headaches, blurred vision, and nausea. The symptoms were not fabricated; he truly suffered from chronic hypertension. But when he accepted a sedative injection from Nurse Marie-Claire, thinking nothing of her soft voice and steady hands, he received something far more destructive.

She administered a compound that induced a micro-bleed in the brain.

Slow.

Untraceable.

Perfectly consistent with untreated hypertension.

Forty-seven hours later, Vogel was dead.

The German doctor in charge declared it a “fatal cerebral hemorrhage,” and Vogel’s body was shipped home.

No autopsy.

No investigation.

No suspicion.

The deportation transports were delayed three weeks—the time required for administrative replacement. In those three weeks, hundreds escaped into hiding.

The Mustering of New Allies

Sister Maria did not operate alone anymore. The network expanded around her like veins around a beating heart.

The Chemist—still hiding in Louvain—traveled sporadically to Brussels under forged papers. He refined her compounds further, developing ways to suspend toxins in saline, to mask their taste in wine, or to embed them in ointments.

The Deserting Soldier, once a Wehrmacht communications officer, helped her intercept German operational memos. He warned her when high-value targets were expected in Brussels.

The Doctor—a quiet Belgian surgeon who despised the occupiers—provided false medical entries, falsified charts, and ensured that death certificates reflected her narrative, not the truth behind it.

The Forger provided her with new identities should one ever become compromised.

Her world became a network of clandestine collaborators, each risking their lives to maintain the façade of normalcy within a machinery of murder.

But none of her allies knew the full scope of her work.

None knew the number of deaths.

None knew what she carried in her Bible.

Only one man besides her had ever glimpsed her true identity—Friedrich Gruber, the Wehrmacht physician back in Louvain. And even he only understood a fraction.

Twelve More Deaths

During 1943 and into early 1944, Sister Maria continued her operations across three cities: Brussels, Liège, and Antwerp. The mobility of her new identity made detection nearly impossible.

She worked as a nurse.

She worked as a caregiver.

She worked as a spiritual counselor for dying soldiers.

And through these roles, she orchestrated the quietest destruction the German command had ever suffered.

Twelve officers died during this time.

One succumbed to a sudden allergic reaction triggered during a routine vaccination.

Another collapsed during a bath, drowned in inches of water after a toxin weakened his cardiac rhythm.

A third died in his sleep after a slow-acting alkaloid mimicked natural organ failure.

Each death had a purpose.

Each death created delay.

She kept a private record in cipher—part of the “Shadow Ministry List”—stored in a sealed envelope in the Louvain monastery vault. It contained names, dates, methods, and consequences. She did not keep these records to boast or to memorialize. She kept them because history needed accuracy, even in darkness.

The list would eventually reach fifty-two names.

Fifty-two men whose violence justified her own.

The Unreachable Target

One name on the list tormented her.

Colonel Otto Lang, the man who had once stared at her across his desk and chosen not to destroy her. A man paradoxically dedicated to preserving the library for ideological reasons while simultaneously enabling the machinery of occupation that crushed her country.

He knew enough to be dangerous.

He suspected enough to be lethal.

He allowed her to live, and by doing so, he kept the war in motion.

She decided, sometime in late 1943, that Lang would eventually have to die.

But the opportunity never came.

He remained in Louvain.

She was in Brussels.

The Gestapo presence around him grew tighter.

And she knew: a natural death for Lang was impossible. He would never ingest a wafer from her hand. He would never accept a sedative from a nun. He would never allow her into his private quarters again.

If she ever killed him, it would not be quietly.

It would not be natural.

It would not be hidden.

But that moment had not yet come.

History would decide when.

1944 — The Year the War Shifted

By mid-1944, the war had changed. Rumors of Allied landings reached the occupied territories. Officers drank more, worried more, and trusted less. Resistance cells grew bolder. The Germans struck back harder. The cycle of violence tightened around Belgian civilians.

Sister Maria worked relentlessly, but the air felt heavier. The sense of impending collapse hovered over every German officer she passed.

Her operations continued, but the rhythm changed.

There was urgency now.

Not panic—purpose.

And then, in September 1944, she received a message from the Shadow Ministry that froze her blood.

It came in the form of a coded letter disguised as a religious donation request.

The message, decoded, read:

“BERLIN ORDERS: BURN LOUVAIN LIBRARY.

DESTRUCTION SCHEDULED WITHDRAWAL PHASE.

IMMEDIATE INTERVENTION REQUIRED.”

She read it twice, then a third time.

The Louvain Library—the collection she had tended, studied, loved—was to be destroyed in the retreating German scorched-earth strategy.

Over four hundred years of human knowledge would be reduced to ash.

The monastery that had raised her would become a ruin.

The manuscripts that had defined her life would vanish.

The memory of her brother, preserved in those shelves, would disappear forever.

This was not strategy.

This was annihilation.

This was evil enacted not upon people but upon history itself.

For the first time since the occupation began, Sister Maria felt something she had never allowed: rage.

Pure. Clear. Righteous.

If she did nothing, the library would burn.

If she acted as she always had—quietly, subtly—it would not be enough.

If she relied on delay, she would lose.

The time for subtlety had ended.

The Final Decision

She chose her path in a moment that felt simultaneously like revelation and betrayal.

She would kill Colonel Otto Lang.

Not with poison.

Not with microdoses.

Not with finesse.

Not with the elegance of her previous work.

She would kill him visibly.

Directly.

Explosively.

She would destroy the one man who held the authority to burn the library.

And she would do it in a way that removed all doubt.

She would take responsibility openly.

For four years she had been a ghost.

For four years she had been a rumor.

Now she would become a declaration.

She prepared a new hollow Bible.

Not for vials.

Not for documents.

But for a weapon.

A Yugoslavian F1 grenade, smuggled by the resistance.

She lined the hollow cavity with padding to reduce sound and friction.

She wrote a note in German—calm, unwavering, final.

“This is for every book you tried to burn.”

“This is for the future you tried to erase.”

“My name is Sister Maria of the Louvain Monastery.”

“I have killed 52 of your officers.”

“This is the only death I sign with my name.”

She folded the note and placed it beneath the grenade.

The Bible closed with a soft, almost reverent whisper.

Her transformation was complete.

Part IV — The Final Appointment

The night she returned to Louvain, the city lay in a muted hush. German convoys rumbled along distant roads, retreating westward in disordered columns. The sound of collapse had a rhythm of its own—metal clattering, boots pounding unevenly, officers shouting at soldiers who no longer believed in victory.

Sister Maria traveled under forged papers, her identity once again shifting to the role that fit the moment: a nun summoned to deliver urgent intelligence to the Colonel. None of the German guards questioned her. Few had the energy left to care.

Her hollow Bible—heavier than the others she had carried—rested in her bag. The weight felt symbolic, like a stone she had chosen to place upon her own chest.

As she walked through the monastery gate, she paused. Four years had passed since the occupation began. Four years since she had hollowed her first Bible. Four years since she had killed her first officer. And now she stood before the building that had shaped both her faith and her rebellion.

She had left it as a silent assassin.

She returned as something else.

Something final.

The monastery corridors were sparsely patrolled now. Many officers had redeployed to reinforce the collapsing defensive lines near Aachen. Colonel Lang, however, remained behind—one of the few senior men still orchestrating German operations in the region. He supervised the planned burning of the Louvain Library personally.

Her footsteps echoed softly on the stone floor as she ascended the stairway toward his office.

The Last Conversation

She knocked on the door.

“Enter,” Lang said without looking up.

His office—it once belonged to the abbott—was cluttered with maps marked with red arrows retreating toward Germany. Reports lay scattered. Two trunks sat by the wall, ready for evacuation.

Sister Maria stepped inside and closed the door behind her.

“Colonel,” she said. “I have information. It concerns the movement of a resistance cell operating in Brussels.”

Lang looked up, startled to see her.

For a moment he just stared, as though seeing a ghost from a time when he still believed the occupation was secure.

“Sister Maria?” he said quietly. “I thought you had been reassigned.”

“I was,” she said. “But what I bring cannot be entrusted to anyone else.”

She placed the hollow Bible on his desk.

Lang glanced at it, then at her face. Something flitted across his expression—curiosity, caution, perhaps a memory of the day he had warned her not to meet with the man in the photograph.

“What is this?” he asked.

“My report,” she said. “Inside.”

He reached for the Bible, but as his hand touched the cover, a realization rippled across his eyes. A flash of recognition, of something too complex to articulate: fear, betrayal, respect, inevitability.

He withdrew his hand slowly.

“Sister Maria,” he said softly. “What have you done?”

Her voice was steady.

“What I must.”

She pulled the pin.

The Blast

The explosion was contained by the room’s thick stone walls. The blast radius was tight, calculated, deliberate. Colonel Lang died instantly, his torso torn apart by shrapnel.

Sister Maria stood several feet back—exactly the distance required to survive, though not unscathed. The shockwave slammed into her. Pain tore up her left arm. Blood erupted across her cheek. Her ears filled with a piercing ring that would never fade.

When the smoke cleared, Lang’s desk was a splintered wreck. Papers floated like ash in the air. His body lay in ruin.

The note she had placed under the grenade fluttered to the floor, half-burned but still legible.

German guards burst into the room. They froze at the sight: a nun standing amid the carnage, face streaked with blood, eyes unblinking, hands lifted slightly away from her sides in surrender.

She didn’t resist.

She didn’t flee.

Her mission was finished.

Interrogation

She was dragged to the basement—formerly a storage area, now a Gestapo interrogation chamber. They bound her wrists. They tore her habit. They demanded names. They demanded networks. They demanded information about poisonings, grenades, collaborators.

For three days they tortured her.

Not with the refined psychological methods of Klaus Müller; he was long gone, reassigned weeks earlier. These interrogators were brutal and inexperienced. They beat her. They submerged her in ice water. They deprived her of sleep. They screamed in her face until their voices cracked.

She spoke only once.

When asked why she killed Lang, she whispered:

“To save the library.”

Her lips bled. Her arm throbbed. Her left ear no longer heard anything but a dull hum.

“Why the others?” they demanded.

She did not answer.

They threatened her with execution.

She did not answer.

They threatened to burn the monastery.

She did not answer.

She had won. Berlin received Lang’s death as evidence of chaos. The burning of the library was postponed while the command structure reorganized. By the time new orders could be issued, Allied forces were approaching.

The library would survive.

Her silence would protect those who remained.

Her torture was merely the final tax she paid for the lives she had saved.

Ravensbrück

She was transferred to Ravensbrück—the largest women’s concentration camp in the Reich—on October 23, 1944. The transport was overcrowded, dark, and suffocating. She arrived barely conscious, her arm infected, her hearing half-gone.

Ravensbrück was a crucible of suffering. Women slept stacked on wooden shelves. Food was watery soup. Guards beat prisoners for the smallest perceived offense. Disease spread faster than hope. Execution squads marched women to the gallows weekly.

Yet even here, she held herself with a strange serenity.

Her fellow prisoners remembered her not for her violence, but for her calm. She prayed not for rescue, but for others. She comforted women dying of exposure or disease. She blessed the bodies of the executed.

They did not know what she had done.

They knew only that she was kind.

By February 1945, her body began to fail. Malnutrition hollowed her face. Pneumonia filled her lungs. Yet she continued to move, to help, to bless.

On February 8, 1945, she collapsed. Prisoners carried her to the infirmary—a place where most entered but did not leave.

She died that night.

The official camp report listed her cause of death as “pneumonia aggravated by starvation.”

But the women who watched her final moments said otherwise.

The Last Walk

Two survivors—years later, in testimonies—claimed that she did not die lying down. They claimed that before her breathing failed, she stood, walked to the door, and paused as though listening to music only she could hear.

They said she moved like a woman returning to a chapel.

They said her face was peaceful.

They said her lips moved as though praying words they could not understand.

When her knees buckled, she did not fall abruptly.

She sank, gently, like a candle extinguishing itself.

They said the prayer she whispered at the end was not one asking for salvation.

It was gratitude.

Liberation and Revelation

Three months later, the war ended.

Ravensbrück was liberated.

The Louvain Library was found intact.

Not a single manuscript had been burned.

Not a single rare volume lost.

The Allies discovered German records detailing how, after Lang’s assassination, a wave of confusion seized the administrative network. The burning orders were delayed repeatedly. No one assumed authority quickly enough to carry them out before retreating forces abandoned the city entirely.

The Shadow Ministry emerged from hiding.

Survivors testified about a woman they called “The Silent Hand.”

Some historians dismissed the legends.

Others dug deeper.

In 1946, during the restoration of the monastery, workers found a sealed envelope in the vault. Inside were ciphered notes, records of names, dates, methods. Not glorification—documentation.

It listed 52 German officers.

And beside each name, a brief annotation:

“Delayed deportation.”

“Prevented execution.”

“Interrupted raid.”

“Protected civilians.”

A second document was found later—the letter written by Dr. Friedrich Gruber, the Wehrmacht physician who had quietly enabled her work. His handwriting confirmed what many had begun to suspect:

The nun with the hollow Bible was real.

And she had killed not out of hatred, but out of necessity.

The Debate

Her legacy divided post-war Belgium.

Some hailed her as a hero, a saint of resistance.

Others condemned her as a murderer who violated her vows.

Still others argued that her story reflected an impossible moral landscape—where no choice was truly righteous, only less evil.

The Catholic Church hesitated to honor her.

Governments debated how to classify her deeds.

Historians questioned whether morality could survive in a world where genocide was official policy.

But one truth persisted:

Without her, thousands would not have survived.

Without her, the Louvain Library would be ash.

Without her, Belgian resistance would have lost its most effective invisible weapon.

She did not live to see the world she helped preserve.

She did not seek recognition.

She did not ask forgiveness.

Her life asked only one question—a question that outlived her:

When evil becomes law,

what becomes the duty of the righteous?

Part V — The Weight of Memory

When the war ended in May 1945, Belgium staggered back into the sunlight like a bruised survivor emerging from years of darkness. Cities were half-ruined, families broken, records scattered, and justice—whatever that meant now—was slow, uneven, and incomplete.

Yet among the wreckage, something miraculous stood untouched:

The Louvain Library.

The Allies entered the monastery expecting to find a charred ruin. Instead, they found the shelves intact, manuscripts undisturbed, and the air smelling faintly of dust and old parchment rather than ash. Scholars wept openly in its halls. Soldiers, hardened by battle, stood in reverent silence at the sight of a treasure that had survived everything humanity threw at it.

No one knew why the Germans had spared it.

No one knew who had stopped the burning.

No one—not at first—knew the price paid in secret.

But soon, piece by piece, the truth surfaced.

The Hollow Bible Emerges

In 1946, as Belgium began restoring historical buildings damaged during occupation, the Brussels Museum of Resistance received an anonymous donation. It arrived in a nondescript crate, wrapped in cloth.

Inside was a single object:

A hollow Bible, its pages precisely carved, its cavity lined with resin, its binding left untouched.

No weapon remained inside.

Just a small folded slip of paper bearing a single sentence:

“Knowledge must survive even when we do not.”

The handwriting was identified—eventually—by surviving monks as belonging to Sister Maria.

The museum displayed the Bible, not understanding its full history. Visitors passed it daily, pausing only briefly, unaware that this quiet, unassuming artifact had once held life and death in equal measure.

It would take another decade before the first serious historian pieced together its significance.

The Cipher List

That same year, renovation workers discovered an envelope sealed in wax deep inside the monastery vault. The wax bore the imprint of the abbott’s ring, but the handwriting on the envelope was clearly feminine. Inside lay closely folded pages covered in cipher.

At first glance, it looked like nothing—scratched symbols, shorthand marks, numbers scattered like debris across the paper. But specialists from the Belgian resistance recognized the coding style. It matched a wartime cipher used only by one cell:

The Shadow Ministry.

It took six months to decode.

When the cipher was unlocked, it revealed a list:

52 German names.

52 dates.

52 causes of death—official and actual.

52 disruptions to Nazi operations.

Next to each name was a short note:

“Deportation delayed by 2 days — 17 escaped.”

“Execution force postponed — prisoners transferred.”

“Search order voided — underground tunnel evacuated.”

“High-value operative escaped capture.”

Each line was a ripple.

Each ripple expanded into a wave.

Each wave saved lives.

Historians counted the indirect consequences and estimated that Sister Maria’s operations were responsible for saving at least 2,847 civilians— Jews smuggled out of Belgium, partisans saved from execution, families shielded from raids, deserters guided to safety.

Some speculated the real number was far higher.

No one could prove it.

No one needed to.

The mathematics of mercy did not require precision to be profound.

The Gruber Letter

The most powerful piece of evidence surfaced unexpectedly in 1949.

When American intelligence declassified certain documents related to Operation Paperclip—the program that recruited German scientists after the war—one file included a personal letter found among the belongings of Dr. Friedrich Gruber, who had died in 1953.

It was the letter he had left for Sister Maria.

“I recognize skilled violence,” it read.

“You have selected only men whose hands were not clean.

Not even by the standards of war.

Finish what you began.”

Signed:

Standartenführer Friedrich Gruber

Wehrmacht Medical Corps

The letter stunned historians.

A Nazi officer, quietly enabling the most prolific resistance assassin in Belgium?

It was an impossibly complex moral curve—one that still baffles scholars today.

Did he regret his service?

Did he see in her a justice he himself could not enact?

Was he trying to salvage his own humanity, one secret at a time?

His motivations died with him.

But his complicity had saved countless lives.

The Scholars’ Debate

In the decades after the war, Sister Maria became a subject of furious academic debate. Conferences in Leuven, Antwerp, Paris, and London all hosted panels about her.

The central questions were always the same:

Was she a hero?

Was she a murderer?

Was she both?

Does motive outweigh method?

Do vows hold meaning during genocide?

The Catholic Church struggled most.

Some clergy argued she had violated sacred principles.

Others insisted her violence was a tragic necessity in a time when evil ruled by law.

The Vatican never officially recognized her actions but privately preserved testimonies about her, acknowledging that morality in wartime defies simple categorization.

Belgian resistance veterans spoke of her with reverence.

One described her as “the quiet rain that wore down the stone of German authority.”

Another called her “the whisper that drowned out the gunfire.”

Not all praised her.

Some believed victory purchased with murder—no matter how justified—was tainted.

But the most thoughtful observers concluded:

“She did what history demanded of her.”

The Prisoners’ Testimony

In 1961, a group of Ravensbrück survivors met in what was then West Germany to record their experiences for a documentary.

One of them—a Polish nurse named Ewa Tomczyk—spoke about “the Belgian nun.”

“She moved among us like light,” Ewa recalled. “Not the kind that warms. The kind that reveals.”

Another survivor, a French political prisoner, softly added:

“She prayed. But not for herself. Never for herself.”

When asked if Sister Maria ever spoke of her past, both women said no.

“She was silent,” Ewa said. “But not the silence of fear. It was the silence of someone who has completed her purpose.”

Her name appeared on the Ravensbrück death registry under prisoner number 45092.

Her cause of death: pneumonia.

Her reality: she had walked toward death with peace, knowing she had protected what mattered most.

The Library That Stood Because of Her

The Louvain Library, whose burning she had prevented, became a symbol of post-war renewal. Its preserved manuscripts became a testament not only to medieval scholars and monks, but to a nun who had chosen to violate every vow she had taken in order to save the written memory of humanity.

Today, historians agree:

Had Colonel Lang lived 48 hours longer, the library would have burned.

Had Sister Maria hesitated for a single day, the manuscripts would be ash.

Had she chosen subtlety instead of the grenade, delay instead of action, the flames would have consumed four centuries of knowledge.

Her final act—violent, undeniable, self-sacrificial—preserved a treasure that would outlive every soldier, every officer, every tyrant who had tried to erase it.

The Museum Display

In Brussels, a glass display case now holds:

The hollow Bible.

The burned edge of Lang’s final note.

A replica of her forged nurse’s identification.

And a detailed map of the deaths documented in the cipher list.

Visitors lean in closely, often expecting a weapon, a dramatic artifact.

Instead, they find an ordinary-looking Bible.

Plain. Worn. Quiet.

Only the placard reveals the truth:

“Used by Sister Maria of Louvain, 1940–1944.

Instrument of resistance.

Tool of survival.

Symbol of moral conflict.”

Children stare at it with wide eyes.

Adults read the placard twice.

Some weep.

Some shake their heads.

Some whisper prayers.

No one leaves unmoved.

The Last Note

In 1973, during an archival reorganization of the monastery, a final piece of her writing surfaced—a short note tucked into the back of a ledger. It was dated October 13, 1944, two days before she killed Colonel Lang.

It read:

“Peace is my vow.

But peace for whom?

For the killers?

For the indifferent?

Or for the ones who might yet live?

If peace demands silence in the face of evil,

then my vow was broken the day evil learned to speak louder than God.”

It was the closest thing she ever left to a confession.

Or a justification.

Or perhaps simply a truth she could not ignore.

Legacy

Seventy years after her death, Sister Maria remains one of the most complex figures in resistance history. Not a soldier. Not a spy. Not a martyr. Not a hero in the traditional sense. Her story does not fit neatly into any mold.

She was a woman of peace who used violence.

A woman of faith who committed murder.

A woman of silence whose actions spoke louder than any sermon.

Some say she saved Belgium.

Some say she saved only a library.

Some say she saved herself from despair by fighting back.

All agree she made history.

Because she understood a truth painfully rare in wartime and even rarer in peace:

Sometimes the only way to defend what is sacred is to be willing to stain your own hands.

The Final Question

Her life leaves behind no clear answers—only a question carved into history like the hollow carved into her Bible:

What will you do

when the world demands

that you become something

you never wanted to be?

This question, more than her kills, more than her methods, more than her sacrifice, is the heart of her legacy.

A legacy not of violence,

not of sanctity,

but of choice.

Choice under impossibility.

Choice under terror.

Choice when all other paths vanished.

And in that impossible corner of human existence, she chose to fight.

Not for glory.

Not for vengeance.

Not even for survival.

But for the lives of strangers

and the survival of knowledge

in a world trying to forget itself.

News

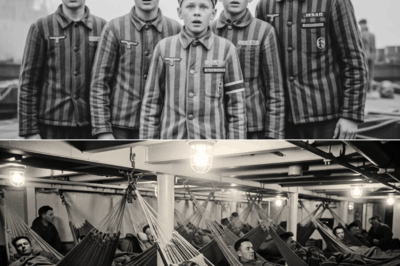

Ch1 “This Can’t Be True,” German Child POW Couldn’t Believe Their First Day in America

April 23rd, 1945. New York Harbor.The fog lifted like a theater curtain, revealing something impossible. 12-year-old Carl Hines Schneider stood…

I Told Her “If You Go On That Trip With Him I’m Out” She Went – And Posted A Bikini Pic With Her Guy Friend. When She Got Back And Saw Who Moved Into Her Place – She Started Trembling

PART 1 — The Line in the Sand If anyone had asked me a year ago whether my marriage would…

When I secretly won millions, I told no one—my parents, my siblings, not even my favorite cousin. Instead, I showed up in “help needed” mode, asked each person a small favor, and quietly watched to see who ignored my calls and who actually came to my house… because only one person said yes.

My name is Ammani Carter and I’m thirty-two years old. At our Sunday dinner last night, I finally worked up…

At my sister’s baby shower, I was nine months pregnant. My parents stopped me at the entrance: “Hold on—your sister isn’t here yet.” I asked to sit down; they told me no.

At my sister’s baby shower, I was 9 months pregnant. When we reached the event, my parents told me, “Wait,…

My daughter-in-law announced at Thanksgiving dinner, “Your late husband signed the house over to us. You get nothing.” Everyone sat in silence. I set my plate down and said, “You should tell them… or should I?” Her smile froze. My son whispered, “Mom, don’t say anything.”

My daughter-in-law announced at Thanksgiving, “Your late husband signed the house to us. You get nothing.” Those words still echo…

“Get Out Of The Pool,” My Mom Ordered — “This Party Is For Perfect Families Only.” And Fifty Guests Watched Us Walk Away In Silence.

THE BEACH HOUSE OWNER Fifty heads turned toward the shallow end. The sun was directly overhead, burning white against the…

End of content

No more pages to load