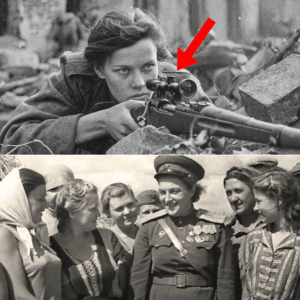

How One Female Sniper’s “CRAZY” Trick Eliminated 309 Germans in Just 11 Months

PART 1 — THE FIRST SHOT

At 5:47 a.m. on August 8th, 1941, twenty-four-year-old Ludmila Pavlichenko crouched behind the shattered remnants of a stone wall on the outskirts of Belailayka, Ukraine. The air tasted like dust and gunpowder. Smoke drifted across the ruined wheat fields, carrying the faint metallic scent of blood. Somewhere beyond the haze, a German sniper was preparing to kill a Soviet soldier — and Ludmila was the only person who knew it.

She had been on the front line for just six hours.

Six hours with no sleep, no food, and no certainty that she would live to see another sunrise. She had only her Mosin-Nagant rifle, forty rounds of ammunition, and a cold, focused fury that had been building since her university in Kyiv was bombed eleven days earlier.

Seventy-three students had died.

Her professor, Dr. Anatoli Vulov, was crushed under rubble.

Her friend Natasha burned alive in the library.

The next morning, Ludmila enlisted.

She did not enlist to be a nurse, although the recruitment officer insisted that’s where women belonged. He told her that combat was no place for a young woman. He laughed when she said she’d been shooting since she was fourteen and had earned top marks in youth competitions.

The laughter died when she put five bullets through a fence post at 100 meters without a single miss.

By the end of that day, she was assigned to the 25th Rifle Division as a sniper.

Now, four months later, she was crouched behind rubble, watching death unfold through a hairline crack in the destroyed wall in front of her.

Across the field, a German sniper lay concealed behind the blown-out corner of a farmhouse. She could see only a sliver of his helmet — barely more than a shadow. He was tracking a Soviet infantryman positioned forty meters to her left.

The Soviet soldier was Sergeant Dmitri Kravchenko, father of two, a man she’d met only yesterday. He had shared his bread with her when she hadn’t eaten for eighteen hours. He had laughed at her jokes. He had asked her about university life, about books, about the world outside the trench lines.

Now he was about to die because he didn’t know someone was aiming at him.

Ludmila inhaled slowly.

Her hands relaxed.

Her heartbeat steadied.

Her world narrowed until there was nothing left except the shot.

Her instructor’s voice returned unbidden from memory:

“Don’t think about killing. Think about solving a problem.

Distance. Wind. Movement.

Shooting is mathematics, not murder.”

She calculated.

Distance: 280 meters.

Wind: light, west to east.

Target: stationary, unaware.

Angle: slight downward elevation.

Her finger brushed the trigger.

This was the moment that would determine everything.

She would either kill — or freeze.

Be a soldier — or an imposter with a rifle.

She exhaled.

The Mosin-Nagant kicked against her shoulder.

The German’s helmet snapped backward. His rifle dropped. His body slumped into the shadows.

Kravchenko ducked instinctively, confused. He didn’t know he’d just been saved.

Ludmila chambered another round.

She expected to feel something — guilt, satisfaction, fear, triumph — but there was nothing. Only the cold clarity of the next task:

Find the next threat.

That morning, she became a sniper.

By the following spring, she would become something else entirely: a legend whose name terrified German soldiers across Eastern Europe.

But that would come later.

First, she had to survive.

THE COST OF FOLLOWING THE RULES

In the weeks after her first kill, Ludmila watched German forces tighten their grip on Ukrainian territory. Entire Soviet battalions were cut down. Medical units overflowed. The front lines shifted. Dozens of her comrades — people she’d eaten with, trained with, marched beside — were dead.

And the snipers were dying fastest of all.

The first she lost was Lieutenant Anna Morozova, an experienced sniper with forty-seven confirmed kills. Morozova was everything Soviet doctrine demanded: precise, disciplined, cautious. She followed every rule in the Red Army’s sniper manual.

Rule 1: Never expose your position.

Rule 2: Fire one shot, then relocate immediately.

Rule 3: Never stay more than thirty minutes in one location.

Rule 4: Always have two or more escape routes.

Rule 5: Avoid patterns at all costs.

On August 19th, Morozova positioned herself on the third floor of a bombed-out apartment building — excellent vantage point, multiple exits, total concealment. She shot a German machine gunner at 320 meters, then moved to her secondary nest on the second floor. She waited twenty minutes, took another shot at 280 meters, killing a German officer.

She was moving to her third position when a single bullet punched through the stairwell window and into her chest.

She died instantly.

The German sniper who killed her was Hans Becker, a Wehrmacht countersniper with eighty-nine kills. Becker specialized in hunting Soviet snipers. He wasn’t just good — he understood the Soviet playbook perfectly.

He knew that Soviet snipers would move after each shot.

He predicted Morozova’s relocation path.

He waited.

He took his shot.

He never missed.

Ludmila was in the same building when Morozova fell. She heard the crack of the rifle. She heard the thud of Morozova’s body. She heard German soldiers laughing.

She didn’t forget that sound.

Two weeks later, the second sniper she knew — nineteen-year-old Corporal Viktor Stepanov — was obliterated by artillery after taking two shots from a drainage ditch. He had done everything right. Perfect concealment. Perfect shooting. Perfect relocation timing.

He died anyway.

German counter-sniper teams knew exactly how Soviet snipers operated. They knew the doctrine. They knew the patterns. They could read Soviet movements like a chess grandmaster reading an amateur opponent.

By early September, seven snipers from Ludmila’s division were dead.

Every one of them had followed doctrine.

Every one of them had been predictable.

Every one of them had died because of it.

That was when Ludmila realized something that changed the course of her life — and the course of sniper warfare.

The Red Army sniper doctrine wasn’t keeping her safe.

It was getting her killed.

If she wanted to survive, she would need to do something so radical, so reckless, so completely forbidden that no instructor would ever teach it.

She would have to use herself as bait.

BAIT: THE UNTHINKABLE STRATEGY

Soviet sniper doctrine insisted that concealment was survival. Exposure meant death.

But German snipers were too skilled.

They hunted shadows.

They anticipated patterns.

They waited for movement.

Ludmila understood then:

If you always hide, the enemy always knows where to look.

If she wanted to kill German snipers, she had to reverse the dynamic. She had to force them to shoot first — and reveal themselves.

So she developed a technique that was not only discouraged, not only forbidden — but considered outright suicidal.

The Dual-Nest Trap

She built two firing positions:

one real, one fake.

Only six to eight meters apart — close enough for her to sprint between them in seconds, far enough apart that a German sniper couldn’t hit both with one angle.

In the primary nest, she placed a decoy:

A helmet on a stick.

A sleeve stuffed with straw.

A silhouette shaped like a sniper preparing to fire.

Then she hid in the secondary position, rifle ready.

She waited.

Sometimes for minutes.

Sometimes for hours.

And eventually — inevitably — a German sniper would take the bait.

A flash.

A crack.

The decoy would jerk backward.

And Ludmila would already be moving, rising, sighting, firing.

Before the German realized his mistake — before he understood the trap — he was dead.

She tested the strategy for the first time on September 3rd, 1941.

The decoy lasted forty-five minutes.

Then a bullet snapped through the helmet.

Ludmila saw the muzzle flash 320 meters away.

She had three seconds.

She fired.

The German dropped.

Two minutes later, two German soldiers dragged a body out from behind the brick wall.

Her first countersniper kill.

Her commanders had no idea she had just committed a blatant violation of the sniper manual. If they had known, she might have been court-martialed.

But Ludmila didn’t care about doctrine.

She cared about surviving.

She cared about her comrades.

She cared about making the German snipers fear her the way they had made Soviet snipers fear them.

Over the next six weeks, she refined the method until she could predict German countersniper behavior with near-perfect accuracy.

By October, she had 78 confirmed kills, including 22 German snipers.

Word spread across Soviet units:

The woman who hunts the hunters.

PART 2 — HUNTING THE HUNTERS

By early October 1941, the German advance across Ukraine had turned enormous swaths of countryside into burnt skeletons of villages and pulverized towns. Entire Soviet units evaporated under artillery barrages, Luftwaffe bombing runs, and methodical infantry pushes. But amid the chaos, one figure moved silently through the ruins — a young woman with a rifle and a strategy no instructor had ever dared to teach.

Ludmila Pavlichenko was becoming a predator.

Her dual-nest bait technique — illegal, suicidal, and completely outside Soviet doctrine — had turned the natural balance of sniper warfare upside down. German countersnipers no longer held the advantage. They were no longer the hunters. They were targets who revealed themselves the moment they squeezed the trigger.

And Ludmila was waiting for them.

For six straight weeks, she refined the technique. She studied German movement patterns, catalogued typical firing angles, learned which buildings German snipers preferred (second and third floors, never the ground floor), and memorized the rhythm of enemy patrols.

The more she learned, the more predictable they became.

And predictability meant death.

THE GERMAN GHOST OF THE RAILWAY JUNCTION

By mid-October, Soviet officers across the sector were whispering her name. Some with awe, some with desperation. Soviet units were bleeding officers at alarming rates, thanks to a German sniper operating near a railway junction just west of Odessa. Over four days, he had killed nine Soviet leaders — commanding officers, communication specialists, radio operators. Anyone with a map or an insignia became a corpse.

His precision was surgical. His timing flawless. His concealment so perfect that entire platoons froze in daylight, terrified to move.

He fired once — then vanished.

No Soviet sniper had even glimpsed his muzzle flash.

On October 12th, Lieutenant Volkov, exhausted, hollow-eyed, and reeking of fear and burned cordite, approached Ludmila with a plea.

“Kill him,” he whispered. “Please. My men won’t step outside. They won’t follow orders. They won’t even breathe loud. You’re the only one who can stop him.”

He offered her vodka. She declined.

He offered extra rations. She shrugged.

He offered gratitude. She ignored it.

She didn’t need rewards.

She needed revenge — for Morozova, for Stepanov, for the snipers whose bodies were now fragments of bone and cloth buried beneath collapsed trenches.

She spent two days observing the junction. From 800 meters away, through a long-range spotting scope, she watched every rooftop, every window frame, every rusted train car.

The German was clever.

He switched positions constantly.

He fired from unexpected angles.

He never gave a clean pattern.

But even the best sniper must follow certain rules of physics and warfare. To see a target, he must place his eyes somewhere. To fire, he must expose himself, if only for half a second.

Ludmila only needed half a second.

She identified eleven possible firing locations the sniper could be using — too many to cover at once. So she decided to force his hand.

This time she didn’t use a straw-stuffed decoy.

She made a full-sized silhouette.

An officer’s coat.

A shaped torso.

A helmet weighted to bob naturally in the breeze.

She placed it in the most tempting location possible — one visible from eight of the eleven likely German positions.

Then she hid twelve meters away, rifle ready, aimed at the spot where she believed the German was most likely to fire from: a blown-open freight boxcar on an abandoned track.

It wasn’t the most obvious sniper nest. It wasn’t even the safest. But that was exactly why Ludmila suspected it. The Germans assumed Soviet artillery wouldn’t waste shells on a single boxcar. And the German sniper knew it.

She waited.

Thirty minutes.

Forty.

Her back throbbed. Her left leg went numb.

Still she waited.

At 7:11 a.m., the shot came.

A single crack.

The decoy’s helmet exploded backward, flipping off like a real head struck by a real bullet.

Through her scope, Ludmila caught the faintest glimmer of muzzle flash — exactly where she’d predicted.

Inside the boxcar.

She moved before her mind even finished confirming it.

Exhale.

Squeeze.

Recoil.

Follow-through.

The German staggered backward but didn’t fall. She’d wounded him, but not enough. He scrambled deeper inside the boxcar.

She didn’t hesitate.

Second shot.

The man dropped.

Volkov’s men later recovered his body.

He had sixty-seven confirmed kills in his logbook.

But his tally ended that morning.

When Volkov asked her how she’d known where he was, she replied:

“I didn’t. I made him shoot first.”

BECOMING A LEGEND

As her kill count rose, the German response grew increasingly desperate. First, a bounty of 100 Reichsmarks was issued for any soldier who killed “the Russian girl sniper.” Then 500. Then 1,000. Eventually, German propagandists insisted she couldn’t exist. They said she was a Soviet invention — a phantom to scare the Wehrmacht.

But dead soldiers don’t lie.

And Ludmila kept leaving bodies.

The Soviets called her Lady Death.

The Germans called her the Red Witch, the Devil Woman, the Ghost of Odessa.

Her favorite nickname, however, came from her own imagination.

Whenever she killed a German sniper, she left a small calling card — a single red playing card tucked into the dead man’s coat.

The Red Queen.

A quiet, ruthless message:

You hunted me.

You failed.

Your turn is over.

Some officers disapproved.

Some applauded.

But all of them knew something had changed:

German snipers — once masters of the battlefield — were now terrified.

Fear makes people sloppy.

Sloppy soldiers die.

Ludmila used that fear like a weapon.

THE MAN WHO KILLED OFFICERS

By November 1941, the front line near Sevastopol was collapsing. German pressure increased daily. Supplies dwindled. Morale hovered on the brink. And then it got worse.

A new German sniper appeared.

He didn’t shoot infantry.

He didn’t target machine gunners or medics.

He only killed officers.

One per morning.

Always between 5:45 and 7:30 a.m.

Always a single shot.

Eleven Soviet officers died in three days.

The effect was catastrophic. Commanders refused to stand near windows. Sergeants hid behind trenches. Soldiers moved without orders, half-mutinous and terrified. A unit without leadership is a unit already defeated.

Soviet command summoned Ludmila.

Major Chernov laid out photographs of the dead.

Entry wounds clean.

Bullet placement immaculate.

Distances consistent.

“This man,” Chernov said, “will collapse the entire sector if he is not killed.”

He gave her forty-eight hours.

If she failed, dozens more would die. The line might break. The Germans could roll through Sevastopol like a tidal wave.

She accepted without hesitation.

Not because she wanted glory.

Not because of the bounty.

Because she remembered Morozova, slumped in the stairwell, and Stepanov, obliterated by artillery, and every friend whose face she could still see when she closed her eyes.

This wasn’t a mission.

It was a death duel.

Two snipers.

One winner.

No second chances.

STUDYING THE KILLER

She spent the first day collecting data.

Every officer who had been shot stood in a similar location at a similar time. Each bullet came from a slightly different angle — northeast one day, southwest the next, northwest after that.

The German was moving constantly.

He followed doctrine perfectly.

Fire once.

Move immediately.

Never repeat a position.

But doctrine couldn’t hide physics.

No matter where he moved, he had to see the officers.

Which meant he had to occupy a vantage point overlooking the command areas.

Ludmila walked the terrain at night with Lieutenant Boris, the reconnaissance officer who survived the siege of Odessa. They whispered their way through ruins, climbed broken staircases, and peered through shattered walls.

She marked every building that offered a clear view of the officer gathering points.

Fourteen possible nests.

Too many to monitor.

So she narrowed it down.

The German always shot early in the morning, when the light favored a sniper facing west. He needed visibility but also shadow. He needed escape routes. He needed elevation.

That left three buildings:

• the ruined church tower

• the roof of the former school

• the third floor of a collapsed apartment block

Of the three, the church tower had the best combination of visibility and darkness.

She chose her battlefield.

Not the decoy.

Not the dual nest.

Not the silhouette trick.

Something far more dangerous.

She would use herself as bait — fully exposed.

Her death, if it happened, would be instantaneous.

THE MOST DANGEROUS MORNING OF HER LIFE

November 8th, 1941

5:42 a.m.

Cold air stabbed at her cheeks. The ruins around her glowed faintly under the pale dawn sky. She wore an officer’s coat — too large, but recognizable. German snipers loved high-value targets. And officers were as high-value as it got.

She stood in the open.

Completely exposed.

Four meters from her rifle.

To any German sniper watching, she would look like an officer gathering for a briefing.

Perfect bait.

Her real rifle was positioned behind rubble, already aimed at the church tower’s third floor.

She counted seconds.

Thirty.

Sixty.

One hundred.

Nothing.

The sun crept higher, turning twisted metal into glinting shards.

Ninety more seconds.

Still nothing.

Maybe she’d miscalculated.

Maybe the sniper wasn’t there.

Maybe he was watching another sector.

Maybe he saw through the trick and—

The shot cracked the air.

A 7.92mm Mauser round screamed past her face, cutting the air with such force that it parted a strand of her hair.

She dove left, not backward.

Her hands hit the dirt.

She rolled.

Blood pounded in her ears.

She grabbed the rifle, turned, sighted.

There — movement — a figure pulling back from the broken archway of the tower.

She had less than two seconds.

She did not calculate wind.

Did not adjust for distance.

Did not breathe.

She simply fired.

The shot hit.

The figure lurched.

Then disappeared into the tower’s shadows.

She held her aim.

Ten seconds.

Twenty.

One minute.

No movement.

When Boris’s clearing team reached the tower eleven minutes later, they found a German sniper on the floor — dead, hit clean through the chest.

In his coat pocket was a logbook.

Ninety-four kills.

Leader of a German counter-sniper unit.

A specialist.

His war ended because Ludmila Pavlichenko was willing to use herself as bait.

PART 3 — LADY DEATH RISES

The death of the German countersniper in the ruined church tower sent a ripple through Soviet lines. Soldiers who had been too afraid to stand upright now stepped from the trenches. Officers who had crouched behind sandbags during briefings now walked openly, though still cautiously. The entire sector exhaled.

For weeks, one German marksman had paralyzed an entire division.

Ludmila had ended him in a single morning.

Word spread.

Whispers first.

Then certainty.

Then legend.

The woman sniper had killed the ghost in the tower.

The Red Army had a hunter of hunters.

Her name became a shield — a psychological anchor in a war that stripped men of identity and hope.

For Soviet soldiers, “Pavlichenko is with us” meant they could sleep a little easier.

For German soldiers, hearing “the girl sniper is here” meant constant dread. No one wanted to raise their head above a trench line. No officer wanted to check his map in daylight. Even hardened veterans flinched at glints of sunlight on metal, afraid they’d been marked by her.

Fear is a weapon.

And Ludmila wielded it without mercy.

THE SIEGE OF SEVASTOPOL

When the surviving elements of Ludmila’s division were redeployed to Sevastopol, the city was already half-ruins. The Germans were tightening a noose around the port. Supplies dwindled daily. Hunger gnawed at every soldier. Ammunition was rationed. Medical supplies evaporated. Every hill became a battleground. Every building turned to rubble.

It was here, amid the carcass of a dying city, that Ludmila’s legend reached its peak.

Her kill count surged.

Her tactics evolved.

Her ruthlessness sharpened.

But it wasn’t just the warfare.

It was the environment.

Sevastopol was a labyrinth of broken walls, collapsed roofs, shattered streets — a sniper’s paradise and nightmare all at once. The terrain hid as much as it exposed, and both sides used the ruins like predators stalking prey through a maze of jagged stone and twisted metal.

German snipers were everywhere.

A new one appeared every few days.

Some were veterans of the Polish campaign.

Some were SS marksmen trained in precision hunting.

Some were arrogant young men who thought killing “the Russian woman” would make them famous.

None of them lasted long.

Ludmila adapted like a creature born to ruin. She learned how sound carried differently across broken stone. She learned which streets funneled wind that curved bullet paths. She learned how shadows shifted at various times of day and how to blend her silhouette into the geometry of wreckage.

While others starved, she hunted.

While others hid, she stalked.

While others feared death, she delivered it.

THE BAIT METHOD REFINED

Her dual-nest bait technique evolved with every engagement.

Where she had once used a helmet on a stick, she now crafted full-bodied silhouettes tied to rubble. She positioned them in predictable Soviet vantage points, daring German countersnipers to shoot. She created illusions of movement by tying fabric to beams that swayed with the breeze, mimicking human motion from a distance.

More than once, Germans wasted entire magazines shooting at ghosts.

And every time they fired, Ludmila noted the muzzle flash, calculated the angle, pinpointed the location — and killed.

She developed a rhythm:

Place decoy.

Wait.

Observe.

Identify.

Eliminate.

Relocate.

Repeat.

Her patience became legendary.

Some days she lay motionless for six hours waiting for a single trigger pull.

Her endurance was astonishing.

Her focus inhuman.

Her technique spread among Soviet snipers. Recruits begged to train with her. Officers rewrote tactical manuals based on her methods. Soviet command began officially logging her notes as instructional material.

It was here, in the ruins of Sevastopol, that she earned the nickname that would follow her for the rest of her life.

“Lady Death.”

A KILL COUNT THAT SHOOK THE ARMY

By January 1942, she had surpassed one hundred kills.

By March, two hundred.

By May, her tally exceeded three hundred.

Her kills were not random infantrymen. At least 187 were officers. Thirty-six were enemy snipers. The rest were machine gunners, artillery spotters, squad leaders — critical battlefield assets.

German units grew paranoid.

Some refused to move without smoke cover.

Others waited for night to relocate.

Some deployed entire squads just to hunt one Soviet sniper — and still died in the attempt.

The Germans increased the bounty on her head again and again.

First 500 marks.

Then 1,000.

Then more than a month’s salary for an entire platoon.

Still no German sniper could beat her.

Still she remained untouchable.

Still her kill count climbed.

THE FOUR WOUNDS

Though she fought like a phantom, Ludmila was still flesh and blood. And Sevastopol was merciless. She collected injuries like medals — each one threatening to end her war, each one pushing her closer to the edge of exhaustion.

First wound:

September 1941 — shrapnel to her arm and shoulder.

A mortar round struck near her firing position.

She bandaged herself and returned to combat the next morning.

Second wound:

December 1941 — concussion from a near-direct artillery hit.

She was knocked unconscious for two minutes.

When she woke up, she insisted on returning to the line.

Third wound:

February 1942 — shrapnel tore into her calf.

She limped through pain for days, unable to relocate quickly, forcing her to temporarily abandon the bait technique.

She recovered just enough to return after three weeks.

Fourth wound:

June 1942 — the one that ended her front-line career.

A German 88 millimeter mortar round buried shrapnel in her face and jaw.

She almost died in the trench before medics dragged her to safety.

Her right eye was damaged.

Her cheek was torn open.

Her jaw fractured.

Even then, she refused to be evacuated until ordered at gunpoint.

Soviet command had seen enough.

She was no longer just a soldier.

She was a symbol — a powerful one.

Her death would be a propaganda disaster.

They pulled her from the front.

Ludmila was furious.

She argued.

She demanded to stay.

She claimed she could still shoot.

Her commanders refused.

Her kill count stood at 309 — the most confirmed kills of any female sniper in recorded history. It was enough. More than enough.

She would not be allowed to die.

FROM THE FRONT LINE TO THE SPOTLIGHT

In July 1942, barely healed and still bearing fresh scars, she was sent to Moscow. Then to Britain. Then, remarkably, to the United States — on a diplomatic tour designed to build Western support for a second front in Europe.

She hated it.

The crowds.

The cameras.

The speeches.

The politicians.

She didn’t want applause.

She didn’t want interviews.

She wanted a rifle and a ruined skyline.

But she understood the mission.

A soldier fights where the war needs them.

If that meant a stage instead of a trench, she would endure it.

In Moscow she received the title Hero of the Soviet Union, the country’s highest honor. She became the first woman sniper in Soviet history to earn it.

Pravda published stories about her.

Radio hosts recited her kill count.

Children memorized her name in school.

The myth grew.

The woman behind it shrank.

But her mission was not yet over.

PART 4 — THE STRANGE NEW WAR

When Ludmila Pavlichenko arrived in Great Britain in late summer of 1942, she was not prepared for the kind of war she would be fighting. She had lived through fourteen months of front-line hell — starvation, artillery barrages, trench rot, sniper duels, and the sight of friends torn apart by shrapnel. But nothing prepared her for microphones, champagne receptions, polite applause, and foreign reporters asking her how it felt to kill people.

She found this world surreal.

Artificial.

Almost grotesque.

In Sevastopol, she had slept in rubble and eaten whatever could be boiled in a tin cup. In London, she slept beneath crystal chandeliers while air-raid sirens wailed somewhere beyond the drapes. People offered her silk gloves. She had spent most of the war without gloves at all.

British newspapers heralded her as a heroic symbol.

American magazines later called her “the most dangerous woman alive.”

Her image was printed in glossy spreads — hair brushed, posture straight, medals pinned.

They wanted a legend.

A story.

A spectacle.

She wanted to go back to her rifle.

MEETING CHURCHILL

Winston Churchill, when he met her, studied her with the fascinated eye of a historian who knew he was shaking hands with someone who had already carved her place into the archives. He asked her to speak about the war. About how she tracked opponents. About whether she felt fear. About how many Germans she had killed.

“Three hundred and nine confirmed,” she answered.

Churchill blinked.

“Confirmed?” he repeated.

“Yes,” she said, unimpressed by his surprise. “Those are the ones that were witnessed. There may have been more.”

He leaned back, trying to picture what “309” meant — the number of men she had watched fall through her scope. He asked if she felt anything when she took a life.

She told him the same thing she told her instructors years earlier:

“It feels like mathematics.

Distance, wind, trajectory.

Solve the equation.

Pull the trigger.”

Churchill laughed, not because he thought it was humorous, but because he had never heard a description of killing so cold and brutally logical.

She did not laugh with him.

THE AMERICAN TOUR

After Britain came something stranger: America.

The United States had never seen anything like Ludmila Pavlichenko. Women in their army were nurses, typists, drivers — but never combatants. Female soldiers with 309 confirmed kills belonged to fiction, not reality.

When she stepped off the ship in New York in September 1942, more than 10,000 people were waiting at the harbor. They cheered, waved flags, held up signs welcoming the “Russian girl sniper.”

Ludmila wanted nothing more than to return to the Eastern Front.

Instead, she was placed into a whirlwind of publicity — speeches, parades, interviews, rallies. She became, overnight, a feminist icon in the West. American women adored her. American men didn’t know what to make of her.

She was too real. Too lethal. Too unlike anything they had been told a woman could be.

In Chicago, she faced a crowd of 20,000 and said:

“Gentlemen, I am twenty-five years old, and I have killed 309 fascist invaders.

Don’t you think you’ve been hiding behind my back long enough?”

The audience exploded.

Reporters printed the line for weeks.

American newspapers argued about her. Some portrayed her as a hero. Others insisted she must be some kind of propaganda invention — no woman could possibly have done what she claimed.

But the War Department verified her kill count using German casualty reports.

The numbers matched.

Ludmila Pavlichenko wasn’t propaganda.

She was simply unprecedented.

FIRST LADY ELEANOR ROOSEVELT

Eleanor Roosevelt was instantly captivated by Ludmila. She admired her not only as a soldier, but as a woman who had shattered every expectation society placed upon her. Roosevelt arranged for her to travel across the country. The two shared long conversations during train rides, far away from cameras.

Roosevelt asked her what she wanted most.

Ludmila answered without hesitation:

“To return to the front.”

Roosevelt shook her head gently.

“You’ve done enough,” she told her. “Your war is over.”

But Ludmila didn’t believe that.

Didn’t accept it.

Didn’t want it.

She felt like a wolf trapped in a cage of velvet curtains and polite applause.

THE BURDEN OF BECOMING A SYMBOL

As the tour continued, the myth of “Lady Death” swelled far beyond the real woman behind it. Posters depicted her with blazing eyes and a rifle slung dramatically across her shoulder. Newspapers exaggerated her demeanor, portraying her as emotionless, steel-hearted, unshakable.

The truth was more complex.

Ludmila slept poorly.

Nightmares woke her with visions of the bombed university, Natasha screaming in the burning library, Morozova falling in the stairwell. She carried guilt for every comrade who didn’t survive. She rarely spoke of them, because each memory felt like reopening a wound.

Yet everywhere she went, people demanded more stories from the battlefield.

“Tell us about your hardest kill.”

“Tell us how it felt.”

“Tell us about the day you became a sniper.”

She gave them answers.

Truthful ones.

But heavily edited — not because she wanted to hide the truth, but because the raw truth would have shattered them.

The truth was simple:

She had survived because she was ruthless.

Because she didn’t freeze when others did.

Because she broke the rules when the rules were killing her comrades.

Because she used herself as bait.

That wasn’t a story people wanted to hear at dinner parties.

So she spoke of mathematics.

Angles.

Wind.

Distance.

Numbers were safe.

Numbers didn’t bleed.

THE END OF THE TOUR

After six exhausting months, her diplomatic tour ended in early 1943. She returned home worn down, older than her age, bearing the weight of two wars — one on the front lines, and one in the spotlight.

Soviet command had already decided her fate.

She would never return to combat.

Her wounds, her symbolic value, and her global fame made her too precious — too politically important — to risk losing in battle.

She was assigned as an instructor to sniper training schools.

This felt like torture at first.

She had gone from dueling German marksmen in burned-out ruins to lecturing teenagers about camouflage patterns.

But gradually, she understood her new purpose.

The war needed more snipers.

Good ones.

Smart ones.

Ones who didn’t make the mistakes that killed Morozova and Stepanov.

So she taught them not just how to shoot — but how to think.

And the students listened.

They hung on every word.

They copied her diagrams.

They memorized her methods.

They practiced her bait technique in controlled drills until it became second nature.

Ludmila Pavlichenko had entered the war as a lone marksman.

She would leave it having reshaped an entire doctrine.

THE LEGACY SPREADS

Many of her students went on to become exceptional snipers themselves.

Vasily Zaitsev, who later became famous for his role in the Battle of Stalingrad, studied her methods and refined them.

Other students carried her tactics across the Eastern Front, passing the knowledge onward until it became standard Red Army practice.

By 1944, Soviet sniper doctrine had formally changed.

Aggression replaced pure concealment.

Deception replaced passivity.

Psychological warfare replaced rigid procedure.

Germany noticed the shift almost immediately.

Casualty rates from Soviet sniper fire increased dramatically.

German soldiers spoke of the terrifying accuracy of “the new Soviet snipers.”

Counter-sniper teams struggled, increasingly outmatched by a generation trained on Lady Death’s methods.

Her shadow stretched across the entire Eastern Front.

She had turned one woman’s survival technique into an army-wide revolution.

AFTER THE WAR

When the war finally ended in 1945, Ludmila was twenty-eight. She returned to Kyiv — the city where she once studied history as a university student. The scars on her face were still visible. Her body carried reminders of every mortar blast and sniper duel she’d survived.

She married twice.

She had one son.

She worked as a historian — the career she had once dreamed of before the bombs fell.

But her war never fully left her.

She avoided public celebrations.

She rarely spoke about her kills.

She disliked when writers exaggerated her legend.

Because the legend wasn’t her.

It never had been.

The legend was bulletproof.

The woman was not.

She passed away from a stroke on October 10th, 1974, at the age of fifty-eight.

The Soviet Union buried her with full military honors.

Western newspapers barely mentioned her.

But soldiers remembered.

Historians remembered.

Her students remembered.

And every sniper in every modern army who learns to use decoys, dual nests, bait shots, and countersniper psychology — whether they know it or not — is learning a technique first perfected by a young woman who refused to die by the rules.

PART 5 — THE WOMAN BEHIND THE SCOPE

For decades after the war, the figure of Ludmila Pavlichenko existed in a kind of duality. In Soviet textbooks, she was the flawless heroine — the unwavering, unstoppable Lady Death who picked off fascists like a reaper with a rifle. In Western depictions, she became a curiosity: a statistical anomaly, a strange exception to the notion of what a woman could be in battle.

But both versions — the perfect legend and the distant symbol — concealed something far more human underneath.

Because the woman behind the scope was neither myth nor anomaly.

She was a flesh-and-blood human being who made a single terrifying decision early in the war:

If the doctrine that was supposed to save me is killing people,

I will break the doctrine.

That decision changed everything.

Not just for her.

Not just for the snipers she trained.

Not just for the soldiers whose lives she saved by eliminating German officers and countersnipers.

It changed how modern warfare understands the psychology of hunting — and being hunted.

And yet, if you walked past Ludmila Pavlichenko on a Kyiv street in the 1960s, you might not have recognized her at all. She lived quietly. She remarried. She had a son. She worked as a historical researcher. She rarely granted interviews. When she did, she downplayed her fame.

She did not boast.

She did not embellish.

She did not claim to be a hero.

But she remembered everything.

Every breath she took while waiting for a German sniper to reveal himself.

Every comrade whose body she carried from the ruins.

Every fragment of shrapnel that tore through her flesh.

Every footstep in the burned-out streets of Sevastopol.

Every time her hands trembled not from fear, but from adrenaline crashing through her veins.

She remembered the smell of burning buildings, the taste of dust, the weight of silence before a kill shot.

She remembered the 309 individuals whose lives she ended.

She often said she remembered their faces.

No propaganda poster ever mentioned that.

THE REAL COST OF 309 KILLS

Numbers carry a strange power in war.

They simplify the unspeakable.

Three hundred and nine.

A tidy number.

A record.

An achievement.

But each one was a person — a son, a brother, a father. Some were older than Ludmila. Some were younger. Some were terrified conscripts. Some were hardened killers. Some were countersnipers, trained to hunt people like her.

She had outthought, outwaited, outshot, outlived them.

But she never celebrated them.

She told one interviewer, years after the war:

“When you kill one man, it is a tragedy.

When you kill hundreds, it is your job.

But it never stops being a tragedy.”

That line never made it to Soviet newspapers.

But her son remembered it.

Her students remembered it.

The few close friends she confided in remembered it.

Behind Lady Death was a woman who understood, more deeply than any historian, the weight of every life taken.

THE EVOLUTION OF A DOCTRINE

Today, every major military sniper school in the world teaches principles derived — directly or indirectly — from Ludmila’s innovations.

Decoys.

Dual nests.

Counter–sniper baiting.

Aggressive psychological tactics.

Unpredictable movement patterns.

Positional triangulation.

Deception firing.

The U.S. Marine Corps Scout Sniper School teaches decoy-based countersniper drills eerily similar to Ludmila’s early dual nests in Odessa. British Special Forces operators analyze pre-engagement behavior of enemy snipers in ways that echo the terrain-mapping methods she developed in Sevastopol. The Israeli Defense Forces incorporate variants of her bait-and-flash reaction protocols.

None of these doctrines mention her name.

The tactics have passed into general military knowledge.

But history knows exactly where they came from.

Not a general.

Not a theorist.

Not a command manual.

But a 24-year-old history student whose university was bombed

and who decided that being prey was unacceptable.

THE ENDURING MYSTERY OF THE SNIPER IN THE BELL TOWER

One of the most enduring stories about Ludmila Pavlichenko is her duel with the German sniper in the church tower — the man whose logbook recorded ninety-four kills.

Western historians have debated his identity for decades.

Was he truly a high-ranking Wehrmacht sniper, a master with nearly a hundred kills?

Was he an amalgamation of several German marksmen she eliminated over weeks of fighting?

Was he a propaganda creation to boost Soviet morale?

The truth, like most things in war, lies somewhere between fact and myth.

Soviet records confirm she killed at least three elite German countersnipers in close succession during that period. Some experts believe the “sniper in the tower” story condensed these engagements into one dramatic narrative — common practice in wartime propaganda.

But Ludmila’s own account — the one she gave to her students — never focused on who he was.

Her focus was on the technique.

The terrain.

The timing.

The psychology.

The courage required to stand in full view, waiting for a bullet with your name on it.

Her story wasn’t about him.

It was about what she was willing to risk to beat him.

And that part, no historian disputes.

She did stand in the open.

She did bait a sniper who had been killing officers daily.

She did dive for her rifle under fire.

She did take a shot without calculating wind or distance.

She did kill the man who had terrorized a Soviet division.

Whether he had ninety-four kills or forty-four doesn’t matter.

History remembers the duel because it encapsulates everything she was:

Disciplined,

innovative,

courageous to the point of insanity,

and utterly unwilling to die by someone else’s rules.

HER FINAL YEARS

The world eventually moved on.

Wars end.

New wars begin.

Legends fade.

Ludmila aged faster than the years suggested.

Her war wounds ached in damp weather.

Her eyesight deteriorated slowly.

She struggled with depression, like so many veterans.

She rarely attended public events.

When people requested autographs, she offered them politely but without enthusiasm.

She did not resent the requests.

She simply didn’t understand why the world wanted the legend when the woman was standing right there.

The truth is that heroes rarely feel like heroes.

They feel tired.

And Ludmila was very, very tired.

But her students visited her often.

Young soldiers she had trained came to her apartment to drink tea and share stories from the front.

They told her they had survived because of lessons she taught.

Some had used her decoy techniques.

Some had avoided death because they remembered her advice:

“If the enemy expects you to be invisible,

then give them something to see —

but make sure it’s not you.”

She would smile softly at that.

Not proudly.

Not boastfully.

But with a kind of quiet sadness — the smile of someone who understood the cost of survival.

THE LASTING LEGACY

When Ludmila Pavlichenko died on October 10th, 1974, the Soviet Union held a full military funeral. Her coffin was draped in red. Veterans saluted. Students from sniper academies stood in formation. Her medals — including Hero of the Soviet Union — glimmered beside her photograph.

Western newspapers barely carried a paragraph about her passing.

But somewhere in the ruins of Sevastopol, her rifle sat preserved in a glass case at the Central Museum of the Armed Forces in Moscow. The wood was worn smooth from thousands of hours of use. The scope bore the small calibrations she scratched into it herself. Her initials were carved faintly near the stock.

Visitors pass it every day.

Some pause.

Some walk past without noticing.

Some lean closer, squinting at the metal plate beneath the glass.

It reads:

“Rifle of Junior Lieutenant Ludmila Pavlichenko.

309 confirmed kills.

Deadliest female sniper in history.”

The plaque is accurate.

But incomplete.

Because Ludmila’s real legacy isn’t in a number.

It isn’t in medals, or propaganda posters, or photographs of her in uniform.

Her legacy is in every sniper who refuses to be predictable.

In every soldier who chooses innovation over doctrine.

In every person who realizes that survival sometimes requires breaking rules written by people who never faced the battlefield.

Her legacy is in the fact that she proved something the world still struggles to accept:

Courage is not male or female.

Genius is not owned by rank or title.

And the deadliest hunter of one of history’s most brutal fronts

was a young woman with a rifle

who refused to be prey.

And now you know her story.

Not the myth.

Not the propaganda.

Not the simplified version.

The real one.

News

I Told Her “If You Go On That Trip With Him I’m Out” She Went – And Posted A Bikini Pic With Her Guy Friend. When She Got Back And Saw Who Moved Into Her Place – She Started Trembling

PART 1 — The Line in the Sand If anyone had asked me a year ago whether my marriage would…

When I secretly won millions, I told no one—my parents, my siblings, not even my favorite cousin. Instead, I showed up in “help needed” mode, asked each person a small favor, and quietly watched to see who ignored my calls and who actually came to my house… because only one person said yes.

My name is Ammani Carter and I’m thirty-two years old. At our Sunday dinner last night, I finally worked up…

At my sister’s baby shower, I was nine months pregnant. My parents stopped me at the entrance: “Hold on—your sister isn’t here yet.” I asked to sit down; they told me no.

At my sister’s baby shower, I was 9 months pregnant. When we reached the event, my parents told me, “Wait,…

My daughter-in-law announced at Thanksgiving dinner, “Your late husband signed the house over to us. You get nothing.” Everyone sat in silence. I set my plate down and said, “You should tell them… or should I?” Her smile froze. My son whispered, “Mom, don’t say anything.”

My daughter-in-law announced at Thanksgiving, “Your late husband signed the house to us. You get nothing.” Those words still echo…

“Get Out Of The Pool,” My Mom Ordered — “This Party Is For Perfect Families Only.” And Fifty Guests Watched Us Walk Away In Silence.

THE BEACH HOUSE OWNER Fifty heads turned toward the shallow end. The sun was directly overhead, burning white against the…

My Parents Sent Me Birthday Chocolates — But When I Said I’d Given Them To The Kids, They Screamed, “What Did You DO?!”

My parents and my sister wouldn’t stop calling about the chocolates. By the time the fifth call came in, I…

End of content

No more pages to load