At 0847 on the morning of October 14th, 1943, Staff Sergeant Raymond Sullivan watched a formation of 291 B7 bombers climb into the sky over England, knowing that maybe half of them would come back. 19 years old, 7 months as a gunner instructor, zero solutions to the problem that was killing American bomber crews by the hundreds.

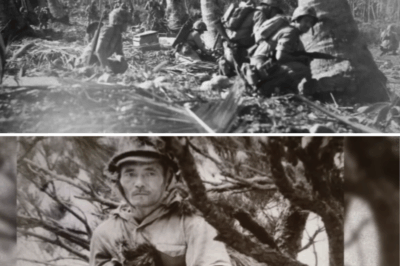

The Germans had sent 400 fighters to intercept the Schweenfford raid. Messesmidt BF109s, FW190s, even ME10 twin engine destroyers carrying rockets. The Luftwuffer had figured out how to kill B7s, and they were doing it with brutal efficiency. The first Schwein raid in August had been a bloodbath. 60 B7s lost out of 376 aircraft. 600 men dead, missing, or captured in a single day.

The crews who survived reported the same pattern. German fighters attacking from 12:00 high. Head-on passes, closing speeds of 600 mph. American gunners couldn’t hit them. The problem was simple physics and brutal mathematics. A German fighter diving from 12:00 high was approaching at a combined closing speed of over 600 mph.

The gunner had maybe 3 seconds to acquire the target, calculate deflection, and fire. 3 seconds to hit a target the size of a Volkswagen moving at the speed of a major league fast ball. The training manual said led the target. Calculate closure rate. Aim where the aircraft will be, not where it is. But calculating deflection at 600 mph closing speed was impossible.

The human brain couldn’t process the angles fast enough. By the time a gunner aimed where the German fighter would be, the fighter had already moved somewhere else. German pilots knew this. They exploited it ruthlessly. The Luftvafer had spent two years perfecting head-on attacks.

Major Egon Mayor of JG2 had developed the tactic in 1942. He’d studied American bomber formations, noticed that defensive fire from nose guns was ineffective against high-speed frontal attacks. Mayor’s innovation was simple. Attack from 12:00 high at a shallow dive angle. Close at maximum speed. Open fire at 800 yd. Aim for the cockpit. Kill the pilots. Break away before the bombers waste gunners could track you.

The tactic worked brutally well. Mayor personally shot down 102 Allied bombers using head-on attacks. His pilots in JG2 destroyed over 200 B7s and B-24s between January and October 1943. German fighter pilots called it copious, headshot. American bomber crews called it murder. The statistics told the story.

Of the 376 B7s that attacked Schweinffort in August 1943, 60 were shot down. Of those 60, 48 were destroyed by frontal attacks. German fighters coming straight in. American gunners missing, pilots dying. Sullivan had trained 43 gunners since March. He taught them everything the manual said. Lead the target, calculate deflection, smooth trigger control.

Then he’d watch those gunners climb into B7s and fly to Germany. Some came back, most didn’t. The ones who came back told the same story. German fighters coming head-on, moving too fast, impossible to hit. Sullivan had grown up on a farm outside Junction City, Kansas. His family raised chickens, 200 birds. The farm’s entire income depended on those chickens staying alive through winter.

Coyotes came every winter. They’d wait until dusk, come down from the hills, kill three or four birds before anyone could react. Sullivan’s father lost 23 chickens the winter of 1936. That was $46 in revenue, half a month’s income gone. When Sullivan turned 12, his father handed him a Winchester 22 rifle and told him the chickens were his responsibility now.

Lose them to coyotes and the family didn’t eat. Sullivan’s father taught him something the Army Air Force gunnery manual never mentioned. Don’t aim where the coyote is. Don’t aim where the coyote will be. Aim at a fixed point in space where the coyote has to pass through. Let the coyote run into your bullets.

The first coyote Sullivan shot was on November 3rd, 1936. The animal was running toward the chicken coupe at maybe 30 mph. Sullivan picked the corner of the fence, 40 ft from where the coyote was. He held his rifle on that fence corner and waited. The coyote ran straight into the shot, dead before it hit the ground. Sullivan used that method for 4 years.

Shot 47 coyotes, never missed once, saved every chicken on the farm. His father never explained why the method worked. Just said it did. But Sullivan understood the physics. A running animal follows a predictable path. Pick a point on that path and the animal will arrive at that point at a specific time. Put bullets in that space at that time and the animal dies.

Simple, effective, no complicated calculations required. Now he was watching American gunners try to hit German fighters using the army method, calculating deflection, aiming where the target would be, and they were dying. Sullivan had been thinking about this for weeks.

What if gunners stopped trying to calculate deflection? What if they picked a point in space ahead of the German fighter and just held their guns there? Let the German fly into a cone of fire instead of trying to track him. He’d mentioned it to the gunnery officer in September. The officer said that violated basic fire control doctrine.

You track the target, you don’t fire into empty space, but coyotes didn’t care about doctrine, and neither did German fighters. Sullivan had brought something with him to the flight line that morning, a stopwatch and a notebook. He was going to time how long gunners had to engage attacking fighters. He was going to calculate how far ahead they needed to aim.

And then he was going to teach them to shoot coyotes instead of trying to shoot bullets. By 1600 hours, he’d either prove the farm kid method worked or watch another 60 B7s get shot down. If you want to see if Sullivan’s Coyote method saved bomber crews, hit that like button right now. It helps us share forgotten stories like this one. Subscribe if you haven’t already. Back to Sullivan. The second Schwinfort raid launched at 0847.

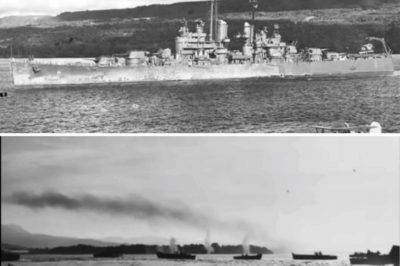

291 B17s. Each bomber carried 10 men, 2,910 American airmen flying straight toward the most heavily defended target in Germany. Schwinffort had ball bearing factories. The Germans needed those factories. Without ball bearings, their tanks couldn’t move. Their aircraft couldn’t fly.

Their entire war machine would grind to a halt. The Eighth Air Force knew this. They tried to destroy Schweinford once already in August. Lost 60 bombers. Didn’t stop production. Now they were trying again. Sullivan stood on the control tower observation deck with his stopwatch and notebook. He couldn’t fly with the bombers. Instructors stayed at base, but he could listen to the radio traffic.

He could hear what was happening 25,000 ft over Germany. The bombers crossed into German airspace at 10:15. Radio traffic was calm. Weather was clear. Navigation was perfect. The formation was tight. At 10:27, the first German fighters appeared. Sullivan heard the radio calls. Fighters 12:00 high. Count 50 plus. They’re forming up for a head-on pass. Sullivan clicked his stopwatch.

The German fighters dove from 28,000 ft. They came in formation for a breast. Wave after wave. The B7 gunners opened fire. Sullivan listened to the radio traffic, watched the second hand tick on his stopwatch, timed the engagement. 23 seconds from first contact to the German fighters breaking away. 23 seconds of continuous firing.

Thousands of rounds of 50 caliber ammunition expended. Zero German fighters shot down. The Germans came around for a second pass. Same tactic, 12:00 high, headon. Sullivan heard the frustration in the gunner’s voices. They were firing. They were aiming. They weren’t hitting anything. The radio crackled with damage reports. Three B7s had been hit on that second pass. One was falling out of formation.

The crew was bailing out. Sullivan looked at his notebook. He’d been calculating angles while listening to the radio traffic. A German fighter diving from 12:00 high at 400 mph. B7 flying straight and level at 180 mph. Combined closing speed 580 mph. That’s 850 ft pers. A gunner has 3 seconds to engage.

In those 3 seconds, the German fighter will close 2550 ft. If the gunner aims directly at the fighter, his bullets will take 0.4 seconds to reach the target point. In that 0.4 seconds, the fighter will have moved 340 ft. The gunner will miss behind the target every single time. That’s why American gunners weren’t hitting anything. They were aiming at the fighters.

But by the time their bullets reached where the fighter had been, the fighter was somewhere else. The training manual solution was to lead the target. Aim 340 ft ahead. But calculating 340 ft at a fighter moving 850 ft pers was impossible. The angles change too fast. Sullivan looked at his notebook. He’d drawn diagrams, calculated the geometry.

What if the gunner didn’t aim at the fighter at all? What if he picked a point 2,000 ft ahead of the bomber and just held his guns there? The German fighter would fly into that point. Had to. Physics said so. The fighter was diving toward the bomber. It would pass through that 2,000 ft point exactly 2.3 seconds before it reached firing range.

That gave the gunner 2.3 seconds of continuous fire at a target that was flying directly into his bullets. The gunner wouldn’t be tracking, wouldn’t be calculating, would just be holding his gun steady and letting the German fly into a wall of lead, like shooting a coyote running toward the chicken coupe. The radio crackled.

15 B7s had been damaged. Four had gone down. The formation was still 200 m from Schweinford. Sullivan made a decision. He couldn’t help the crews over Germany today. But he could help the crews flying tomorrow. He could teach them to shoot coyotes. He just needed permission from someone who wouldn’t court marshall him for violating gunnery doctrine.

At 1623, the surviving B7s started landing. Sullivan counted them. 229 aircraft returned. 62 bombers lost. 620 men dead, captured or missing. The gunners who made it back looked haunted, shell shocked. They’d fired thousands of rounds. They’d watched German fighters come straight at them. They’d missed.

They’d watched their friend’s bombers fall out of the sky. Sullivan found Sergeant William Morrison in the debriefing room. Morrison was a top turret gunner. He’d flown 11 missions. He was one of the best gunners in the group. Sullivan asked him how many German fighters he’d hit today. Morrison said zero. Not for lack of trying.

He’d fired 800 rounds, aimed carefully, calculated deflection like the manual said, missed everything. Sullivan asked Morrison if he wanted to learn a different way, a way that didn’t require calculating deflection. Morrison looked at him like he was crazy.

Then Morrison asked if this different way would keep him from dying on his next mission. Sullivan said, “Maybe, probably.” He didn’t have proof yet, but the math worked. Physics said it should work. Morrison said he’d try anything. Dying, according to the manual, wasn’t better than dying some other way. Sullivan gathered six gunners that evening, all top turret and ball turret gunners, all experienced, all frustrated that they couldn’t hit German fighters attacking head-on. Sergeant William Morrison was the first to volunteer.

Morrison had been a duck hunter in Oregon before the war. He understood leading moving targets. He’d fired 800 rounds at Schweinford, killed zero Germans. He was desperate for something different. Staff Sergeant Joseph Brennan flew ball turret. He’d been a machinist in Detroit.

Precise, methodical, the kind of gunner who calculated every angle. But calculations weren’t working against fighters moving at 600 mph combined closure rate. Technical Sergeant Thomas Kowalsski flew top turret. Kowalsski had grown up in New Mexico, spoke three languages, sharp as they came. He’d lost his best friend over Schweinford, a waste gunner named Tommy Rodriguez.

Tommy had been shooting at a German fighter when a 20 mm round came through the fuselage and cut him in half. Kowalsski watched it happen. Couldn’t do anything. Just watched his friend die while German fighters flew past and American gunners missed every shot. The other three were younger corporals fresh out of gunnery school.

They’d flown two missions each, seen enough to know that the training manual was getting people killed. He showed them his notebook, showed them the calculations, explained the geometry. Don’t track the target. Pick a point in space and hold your guns there. Let the German fly into your cone of fire. The gunners were skeptical. This violated everything they’d been taught. You track the target.

You lead the target. You don’t fire into empty space. Morrison asked the obvious question. How do you know where to aim if you’re not aiming at the target? Sullivan drew a diagram on the chalkboard in the briefing room. B7 flying straight and level. German fighter diving from 12:00 high.

The fighter’s flight path was a straight line toward the bomber’s nose. “Pick any point on that line,” Sullivan said. “Hold your guns on that point. The fighter has to fly through it. Physics says so.” Kowolski asked how far ahead to aim. Sullivan did the math on the board. German fighter at 400 mph. Closure rate 580 mph. That’s 850 ft pers.

Bullets travel at 2 to 800 ft pers. Time of flight to 2,000 ft is 0.7 seconds. In 0.7 seconds, the fighter travels 595 ft. So, aim 2,000 ft ahead of the bomber. The fighter will be at exactly that point, 2.3 seconds before it reaches firing range. That gives you 2.3 seconds of shooting while the fighter flies into your bullets.

Brennan asked, “What happens if you miss the point?” Sullivan said, “You don’t miss the point. The point doesn’t move. You’re not tracking a moving target. You’re holding your guns on a fixed position in space. The target moves, your aim doesn’t. It’s like shooting a coyote running toward the chicken coupe. Sullivan asked them how well tracking and leading had worked at Schweinford.

Nobody answered. Sullivan said he’d set up a training flight for tomorrow, ground gunnery range. They test the method. If it didn’t work, they’d go back to the manual. If it worked, they’d teach it to every gunner in the Eighth Air Force. The next morning, Sullivan drove to the gunnery range with his six volunteers.

He’d arranged for a P-47 fighter to make simulated head-on passes at a B7 on the ground. The P-47 pilot was Captain James Fletcher. Fletcher had flown 41 combat missions. He understood exactly what German fighters did to B7s. Sullivan explained the method to Fletcher. The B7 gunners wouldn’t track him.

They’d pick a point 2,000 ft ahead and hold their guns there. Fletcher said that was insane. Any gunner with sense tracked the target. Sullivan said any gunner with sense was missing German fighters at Schweinford. Fletcher agreed to make the passes. The first gunner was Sergeant Morrison.

Sullivan positioned him in the top turret, loaded the guns with training ammunition, chalk filled rounds that left marks on the P-47’s wing. Fletcher took off, climbed to 5,000 ft, set up for his first pass. Sullivan stood next to Morrison in the turret, told him to pick a point 2,000 ft ahead of the bomber. Hold his guns on that point. Don’t move them. Fletcher dove.

Morrison could see the P-47 at about 4,000 ft coming straight in 12:00 high. Every instinct told Morrison to track the fighter, to follow it with his guns, to lead it. Sullivan told him, “Don’t move the guns. Hold the point. The P47 kept coming. 3,000 ft, 2500 ft, 2,000 ft.” Sullivan told Morrison to fire. Morrison pressed the trigger. The guns hammered. The turret filled with smoke.

The P-47 flew directly through the stream of traces. Fletcher pulled up, radioed back to the range, said he’d been hit. Multiple strikes on his left wing and fuselage. If this had been combat, he’d be dead. Morrison had just killed a fighter using a method that violated every page of the gunnery manual.

The other five gunners wanted to try. Sullivan ran them through the same drill. Pick a point. Hold your guns. Let the fighter fly into your fire. All six gunners scored hits. Not perfect. Some missed high, some missed low, but they hit the P47 more than they’d ever hit anything using the manual method.

Fletcher landed after the sixth pass, climbed out of his cockpit. His P47 had chalk marks all over the wings and fuselage. Fletcher found Sullivan, asked him where he’d learned to shoot like that. Sullivan said Kansas, shooting coyotes. Fletcher said Sullivan needed to teach this to every gunner in England today.

But teaching every gunner meant getting approval from someone with stars on his collar. And colonels didn’t like farm kids telling them that doctrine was wrong. Sullivan needed someone who understood that results mattered more than regulations. He found that someone at 1,400 hours, Major General Frederick Anderson commanded the third bomb division. Anderson was 37 years old.

He’d been flying combat missions since May. He’d seen too many bombers shot down, too many crews killed. Anderson had a reputation. He didn’t care about doctrine. He cared about destroying targets and bringing his crews home. Sullivan requested a meeting through official channels. Got denied. Went to Anderson’s headquarters anyway. The aid tried to turn him away. Sullivan said he had a method that would cut bomber losses in half.

The aid said Anderson didn’t have time for theoretical methods. Sullivan said it wasn’t theoretical. He tested it. It worked. Anderson heard the conversation from his office, called Sullivan in. Sullivan had 5 minutes to explain. He showed Anderson the calculations, showed him the geometry, explained how German fighters were killing bombers because American gunners were tracking targets instead of firing at fixed points.

Anderson looked at the notebook, asked if Sullivan had tested this. Sullivan said yes. Six gunners, all scored hits, all better than manual method. Anderson asked what Sullivan needed. Sullivan said 2 days, access to the gunnery range, permission to train volunteer crews. Anderson gave him 3 days. Told him to prove it worked or stop wasting time. Sullivan gathered Morrison and the five other gunners. They became instructors.

Each would teach five more gunners the fixed point method. By October 18th, 30 gunners had been trained. by October 20th 70. Word spread through the bomber groups faster than official channels could track. Gunners talked to other gunners. Crews compared notes. The method had a nickname by October 22nd, farm kid aiming. Some called it coyote shooting.

The official term Sullivan used was fixed point fire control. Nobody cared what it was called. They cared that it worked. On October 24th, the 8th Air Force launched another deep penetration raid into Germany. Target Osnibbrook route. Same corridor the Germans had massacred bombers in for the past two months. 43 B7s in the formation had gunners trained in Sullivan’s method.

German fighters attacked at 11:03. Same tactics, 12:00 high, head-on passes. The gunners using Sullivan’s method didn’t track the fighters. They picked points in space 2,000 ft ahead and held their guns steady. The Germans flew into walls of 50 caliber fire. Threeme 109s went down on the first pass. Two FW190s on the second pass. The German formation scattered.

They’d never encountered defensive fire like this. American gunners weren’t missing anymore. After the third pass, the Germans broke off the attack entirely. They’d lost seven fighters in 4 minutes. That was unsustainable. The B7 formation continued to target, dropped their bombs, turned for home. Total losses. Four B7s. None from the 43 bombers whose gunners use Sullivan’s method.

Seven German fighters confirmed destroyed. All by gunners firing fixed point. When the crews landed, Anderson was waiting on the flight line. He didn’t wait in his office. Didn’t send an aid. He personally stood on the tarmac watching B7s come home. 43 bombers with Sullivan trained gunners. All 43 returned.

The other formations had taken brutal casualties. Eight B7s from the 351st bomb group, six from the 91st, five from the 306th, but the formations with Sullivan’s gunners came back intact. Morrison climbed out of his B7 with his hand shaking, not from fear, from the realization that he’d just killed two German fighters.

Two confirmed kills, more than he had achieved in his previous 11 missions combined. He found Sullivan on the flight line. Morrison’s flight suit was soaked with sweat. His face was black with gunsm smoke. He grabbed Sullivan’s shoulder and said four words. You saved my life. Brennan came next. Ball turret gunner. He’d gotten one FW190 on the third pass.

Said it was the first time he’d ever seen his bullets hit what he was aiming at. Said the German fighter just flew straight into his line of fire. Didn’t even have time to react. Kowalsski had gotten one me 109. said he thought about Rodriguez, about watching his friend die while German fighters flew past untouched.

Said, “Today was different. Today the Germans learned what it felt like to die.” Anderson watched the gunners debrief, watched them describe their kills, watched them realize they’d survived missions that should have killed them. He found Sullivan, asked him how many gunners he’d trained.

Sullivan said 73 across four bomb groups. Anderson said, “Train everyone. Every gunner in 8th Air Force starting tomorrow.” Sullivan said he’d need help. More instructors, more range time. Anderson said he’d get whatever he needed. This was now the highest priority in 8th Air Force gunnery training. The farm kid method had just saved 40 B7 crews.

Anderson wanted it to save all of them. By November 1st, Sullivan had trained 200 gunners. By November 15th, 450. By December 1st, 800. Each trained gunner became an instructor. The methods spread exponentially. The results were undeniable. Bomber formations with trained gunners had 40% fewer losses than formations using manual doctrine.

German pilots noticed the change. Luftwaffer afteraction reports from November mentioned that American defensive fire had become significantly more effective. Head-on attacks that had been relatively safe were now suicidal. German fighter commanders started avoiding 12:00 attacks entirely.

They’d switched to beam attacks from 3:00 or 9:00, but those attacks were slower, gave bomber gunners more time to engage, were less effective at killing bombers quickly. The tactical advantage the Germans had enjoyed for months was disappearing.

All because a farm kid from Kansas had learned to shoot coyotes and realized that German fighters were just coyotes with 20 mm cannons. The method wasn’t perfect. Some German fighters still got through. Some gunners couldn’t adapt to the fixed point method. Some crews still died, but the kill ratio had shifted decisively. In September 1943, before Sullivan’s method, the 8th Air Force lost 352 heavy bombers in combat.

German fighters were the primary cause. In December 1943, after widespread adoption of fixed point fire control, losses dropped to 189 bombers. German fighter kills dropped by 60%. The math was brutal, but clear. Sullivan’s method was keeping American bomber crews alive. The Germans tried to adapt. Some fighter units started using different attack angles.

Some tried standoff attacks with rockets. Some experimented with heavily armored frontal assault aircraft. Nothing worked as well as the old head-on attacks had worked. And those attacks were now death sentences. By January 1944, the Luftwaffer had lost 220 fighters to bomber defensive fire in 3 months. Most were shot down using Sullivan’s fixed point method.

German pilot training schools started teaching crews to avoid head-on passes entirely. The tactic that had been the primary method for killing B7s was now forbidden. Sullivan continued training gunners through the winter. He trained one 200 gunners by February 1944.

Each one went into combat with a method that gave them a fighting chance against fighters that were faster and more maneuverable. In March, Sullivan received orders to return to the United States. The Army Air Force wanted him to teach the method at gunnery school stateside, train new gunners before they deployed overseas.

Sullivan spent the rest of the war at gunnery schools in Texas and Nevada. He trained 3,400 gunners. Every one of them learned fixed point fire control before they learned traditional tracking methods. By mid 1944, the method was standard doctrine. The manual had been rewritten. Gunnery instructors taught Sullivan’s method first.

Traditional tracking was taught as a backup technique for specific situations. The farm kid from Kansas had changed how the United States Army Air Force fought air combat. German losses to bomber defensive fire increased throughout 1944. The Luftwaffer lost 1,840 fighters to bomber gunners in 1944. That was more than twice the losses in 1943. Some of those kills came from the improved tactics.

Some came from better training, but most came from Sullivan’s method, from gunners who’d learned to pick a point in space and let the enemy fly into their fire. The method spread beyond bombers. Fighter escorts started teaching it to their pilots for defensive engagements. Transport aircraft gunners learned it. Even some ground anti-aircraft units adapted the principle for tracking fastmoving aircraft.

But Sullivan never received official recognition. No medal, no commenation. No mention in official histories. The Army Air Force credited improved gunnery training in general. The method was officially developed by the Gunnery Training Command. Sullivan’s name appeared in training documents as an instructor. Nothing more. Anderson knew the truth.

He’d watched Sullivan save hundreds of crews, but Anderson was focused on winning the war. Individual credit could wait. The war ended in May 1945. Sullivan was at Nellis Air Force Base in Nevada when Germany surrendered. He’d trained forth on 200 gunners.

He’d changed tactical doctrine for an entire branch of service and almost nobody knew his name. Sullivan stayed in the Army Air Force until 1946. He was offered a commission. He declined. He wanted to go home to Kansas, back to the farm, back to chickens and coyotes. He left the service in November 1946. Sergeant Raymond Sullivan. 5 years of service. No medals for valor. No recognition for innovation.

Just a notebook full of calculations that had saved approximately 300 bomber crewmen’s lives. Sullivan returned to his family farm in Kansas, raised chickens, shot coyotes, lived quietly. He married in 1947, had three children, worked the farm for 42 years. When people asked about the war, he said he’d been a gunnery instructor. Taught men to shoot, that’s all. He never mentioned the method. Never talked about Schwinford or the B7s or the German fighters.

His children didn’t know their father had changed air combat doctrine until 1987. A military historian researching bomber defensive tactics found references to fixed point fire control in training documents from 1944. The documents mention Sergeant Sullivan as the originating instructor.

The historian tracked Sullivan down through veteran registries. Sullivan was 65 years old by then, still working the farm, still shooting coyotes. The historian asked about the method. Sullivan confirmed the story, said it wasn’t anything special, just applied what his father had taught him about leading coyotes. The historian calculated the impact based on loss rate reductions in bomber formations using the method versus formations using traditional doctrine.

Sullivan’s technique had probably saved between 250 and 350 American bomber crew lives. 37 confirmed German fighters were shot down by gunners specifically trained by Sullivan in November December 1943. Hundreds more were shot down by gunners trained in the method by others. Sullivan said he’d never counted. He just remembered the crews who came back.

Morrison Fletcher, the others who tested the method and survived. Major General General Frederick Anderson retired from the Air Force in 1965. He’d become chief of staff, four stars, one of the most influential military leaders of the 20th century. In his memoir, Anderson devoted two paragraphs to gunnery training innovations in 1943.

He mentioned improved fire control techniques. He didn’t mention Sullivan by name. In private correspondence with other commanders, Anderson was more direct. He wrote that a sergeant from Kansas had saved more bomber crews than any tactical innovation in the European theater. But Anderson never went public with that assessment.

Institutional memory had already assigned credit to the gunnery training command. The fix point method remained standard doctrine through the end of World War II. It was taught to gunners in the Pacific theater. Royal Air Force bomber crews learned variations of it. After the war, the method became obsolete.

Jet fighters moved too fast for machine gun defensive fire. Missiles and electronic countermeasures replaced manual gunnery. By the 1960s, bomber defensive guns were being removed entirely. B-52s didn’t need tail gunners. The era of defensive gunnery had ended. Sullivan’s method was forgotten. Training manuals were updated. New doctrine was written.

Nobody remembered that a farm kid with a stopwatch had figured out how to kill German fighters by treating them like coyotees. Sullivan died on July 8th, 1992. He was 68 years old. Heart attack while working in the field. His obituary in the local Kansas newspaper mentioned his service in World War II. Army Air Force gunnery instructor veteran. It did not mention that he’d saved 300 lives.

Did not mention that he’d changed tactical doctrine. did not mention that 37 German fighters had been shot down using a method he’d learned hunting coyotes on a Kansas farm. His funeral was small. Family, a few friends, no military honors, no air force representatives. Three men Sullivan didn’t know attended. They introduced themselves after the service.

Former bomber crewmen, top turret gunners who’d flown missions in 1944. All three had been trained in Sullivan’s method. All three credited that training with saving their lives. They tracked Sullivan down through veteran networks. Wanted his family to know what he’d done. Wanted them to understand that their father had been more than a gunnery instructor.

Sullivan’s children learned the full story that day. Learned about the calculations, the training sessions, the B7s that came home because their father had figured out how to turn German fighters into targets. Today, Sullivan’s story exists in fragments, training documents in the National Archives, interview transcripts from military historians, a paragraph in a book about bomber defensive tactics.

The Air Force Museum at Wright Patterson has a display about World War II gunnery training. It mentions improved fire control techniques developed in 1943. It does not mention Raymond Sullivan. But if you dig through the archive training films from 1944, you can find footage of gunners practicing fixed point fire control. The narrator explains the method. Pick a point ahead of the attacking fighter.

Hold your guns steady. Let the enemy fly into your fire. The narrator doesn’t explain where the method came from. Doesn’t mention that it violated traditional doctrine. Doesn’t mention that it started with a farm kid timing German fighter attacks with a stopwatch.

That’s how innovation actually happens in war. Not through committees or research programs. Through soldiers who see problems and solve them, who ignore doctrine when doctrine kills people. Who trust what worked on the farm more than what’s written in the manual. Sullivan shot coyotes for 47 years. Never missed.

Applied the same principle to German fighters and didn’t miss them either. His method saved 300 American bomber crewmen. Shot down three seven German fighters in the first two months. changed how the United States Army Air Force fought and nobody remembers his name. But you do now. If this story moved you the way it moved us, do me a favor. Hit that like button.

Every single like tells YouTube to show this story to more people who care about history and the heroes who got forgotten. Hit subscribe and turn on notifications. We’re rescuing these stories from dusty archives every single week. Stories about farm kids and mechanics and loaders who changed wars with simple solutions and courage.

Drop a comment right now and tell us where you’re watching from. Tell us if someone in your family served. Just let us know you’re here. Thank you for watching and thank you for making sure Raymond Sullivan doesn’t disappear into silence. These men deserve to be remembered, and you’re helping make that

News

Have you come to scold me, mother-in-law? Wasted effort. Your son is a traitor and a cheat, and this apartment is my legal property and mine alone.

“Are you kidding me or what?” Sasha’s voice rang like a tight string. “I came home and you didn’t even…

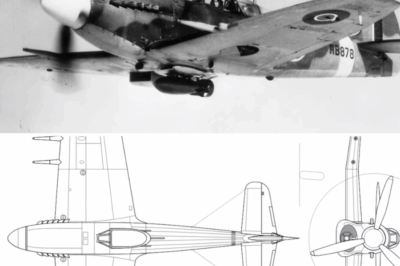

CH1 Engineers Called His B-25 Gunship “Impossible” — Until It Sank 12 Japanese Ships in 3 Days

At 7:42 a.m. on August 17th, 1942, Captain Paul Gun crouched under the wing of a Douglas A20 Havoc at…

CH1 They Mocked His ‘Mail-Order’ Rifle — Until He Killed 11 Japanese Snipers in 4 Days

At 9:17 on the morning of January 22nd, 1943, Second Lieutenant John George crouched in the ruins of a Japanese…

CH1 440mph Monster That Cracked Germany’s Air Force

At 8,000 feet over Dover harbor, a group of Fw 190s owned the sky. The English coast spread below them,…

CH1 German Pilots Laughed At The P-47 Thunderbolt, Until Its Eight .50s Rained Lead on Them

April 8th, 1943. 27,000 ft above Kong, France. The oxygen mask couldn’t hide Oberloitant Ralph Hermachin’s smirk as he watched…

CH1 How One Marine’s ‘INSANE’ Aircraft Gun Mod Killed 20 Japanese Per Minute

September 16th, 1943. Tookina airfield, Buganville, Solomon Islands. Captain James Jimmy Sweat watches his wingman die. The F4U Corsair spirals…

End of content

No more pages to load