A soft knock. That was all.

Not a bang, not a fist. A careful tapping that sounded as if the knuckles themselves were afraid. I froze in the middle of the bridal suite, the hem of my dress pooling like a pale lake at my feet. The hotel air smelled of gardenias and hair spray and the faint iron of the straight pins still tucked into the seamstress’s cushion. We were at my husband’s family estate, though the wing they’d given me for the afternoon felt more like a museum than a home—oil portraits watching from the walls, carpets you wanted to tiptoe across.

Who knocks like that at this hour?

I moved to the door and opened it just a sliver. In the narrow gap—between gleaming brass and polished wood—I saw the eyes of the woman who’d worked in this household longer than I’d been alive.

They were not the eyes of someone who gossips.

They were the eyes of someone who has decided to risk her life.

“If you want to survive,” she whispered, voice shaking, “change your clothes and leave through the back door. Now. If you hesitate, it will be too late.”

Words rose to my lips—What? Why?—and died there. Her pupils widened, pleading. From the corridor, heavy footsteps struck the marble: measured, sure, a man comfortable in halls where other people were taught to be quiet.

My new husband.

I had a choice to make—in the time it takes to inhale.

Stay and face him.

Or run and face the night.

The body knows before the brain does. My fingers were already searching for the zipper. I dragged the dress down to my waist with hands that weren’t entirely mine, found a gray T-shirt and jeans in the wardrobe that shouldn’t have been there, and climbed into them. The wedding gown bunched, then slid as I shoved it beneath the bed. I slipped through the side door, the one that opened onto a service corridor, the one that smelled like lemon cleanser and steam. The housemaid—Sáu—pushed open a wooden gate that had been painted a lifetime ago and whispered one last order into the cold.

“Go straight. Don’t look back. Someone is waiting.”

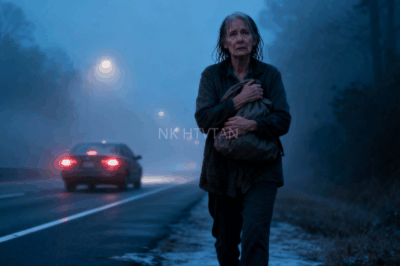

I ran.

The back alley sliced me with its air. I reached the streetlight to find a motorcycle idling in the jaundiced glow, the driver’s helmet low over his brow. He said nothing. He just reached for my wrist, pulled me onto the seat, and we were a gray bullet cutting through a night that did not ask why.

I clung to the stranger’s coat like its seams could hold a life together. Wind slapped my face. Tears broke and froze and broke again.

Nearly an hour later, out beyond the city’s edge where the neon thinned into fields and the roads were stitched with dirt, the bike slowed beside a small cinderblock house with a corrugated tin roof. The man killed the engine. Crickets took back the night. He led me inside and said, very softly, as if the walls were listening:

“Stay here for now. You’re safe.”

It’s strange what the body does with safety. Mine collapsed into a chair as if my bones had been removed. Questions roared into the empty space that adrenaline left behind—Why had the maid saved me? What was happening in that house? Who had I just married?

Outside, the night was still. Inside me, a storm began.

I didn’t sleep so much as surface and sink. Every distant car door, every dog bark, every thread of wind snapping the banana leaves sent me choking back to awareness. The man who had brought me—Quang, as I learned later—sat on the porch smoking in the blue-gray before dawn. His cigarette flared a small orange thought. He didn’t ask me anything. I didn’t ask him anything. We shared a caution neither of us had the right words for.

When the sun finally smudged the horizon, the housemaid returned.

Gratitude knocked me forward. I fell to my knees hard enough that my palms stung on the concrete.

“No kneeling,” she scolded, brisk hand hauling me upright. “Stand up. Listen. You must know the truth. Only truth keeps you alive.”

She was not a dramatic woman. She was practical, the kind of person who knows the exact number of towels in a cupboard. That made what came next land even harder.

“Their money is not clean,” she said flatly. “Everything looks white on the outside—charity balls, foundation photos, politicians shaking hands—but inside is mud. Your marriage is not for love. It is to settle debt. That is why he asked his mother to find him a wife like you. Quiet. Alone.”

I had known something was wrong in the way you know a tremor before you see the chandelier sway. A line of memory ambushed me: the ceremony, the ring too tight, my husband’s grip tightening on my wrist until there was a white mark where his fingers had been. I had told myself he was nervous.

I had told myself so many stories.

“There is more,” Sáu said, lowering her voice as if the walls had ears. “A young woman—years ago. She did not walk out of that house. People with loud voices were paid to be quiet. People with quiet voices were taught to be quieter. After that, the house became…hungry. Do you understand?”

I did.

“You must leave,” the man from the porch said. His voice had the careful weight of someone deciding where to put a foot in a minefield. “Truly leave. Change your name, your phone. If you think this is a movie, you will be dead by the next scene.”

“I have nothing,” I said. “They took my phone at the temple—‘so I could be present.’ My wallet’s still on the vanity. I don’t even have bus money.”

Sáu pressed a cloth pouch into my hands. Inside: a sheaf of bills; an old phone with a spiderweb crack; my identification card, slightly bent, with my face looking back at me as if she did not know me.

She had stolen these things back for me while pretending not to see.

Tears burned my eyes. Panic wears the same clothes as gratitude. I pulled the old phone apart. Two signals flickered. One of them led to my mother.

When she answered, the sound of her voice undid me. I wanted to tell her everything and could not. The housemaid stood in front of the table, shaking her head. “Not where you are,” she whispered. “Not names.”

“I’m safe,” I told my mother. “For now.” She cried like a woman who had held her breath for too long. “Stay alive,” she said like a prayer. “We’ll find a way. Stay alive.”

Days became a routine built from fear. Quang brought food—banh mi wrapped in paper, boiled eggs, bags of rice—and disappeared. Sáu returned to the house every morning and glided through it the way she had the day before, as if nothing under those roofs had shifted. I learned to move through the little house like a ghost who hadn’t yet decided whether to haunt it.

“What do I do?” I asked into the air one evening, the question not meant for anyone in particular. “Hide forever?”

The maid shook her head. “No. After a while, they find what they want. Men who think they own everything hate empty spaces. They will hunt the absence until they fill it.”

“How?” I said. “How do I stop them?”

“You make the absence theirs,” she said. “You take everything they hide and put it in the light.”

That was when she told me about the papers.

“He keeps records,” she said. “He thinks paper makes him untouchable. I have old things—for years I’ve kept the small copies when he made big ones. If we bring them to the police, they must listen.”

“Will they?” Quang asked. He had the watchful look of a man who has seen what money can toppling. “Truth is a thing you have to keep pointing to. Otherwise, other people will point somewhere else.”

“We’ll make them look,” she said.

We planned like burglars. We marked doors and lights and which floorboards squeaked; we built times around habits. We did not say the husband’s name out loud. We did not practice bravery. We mapped it.

The night we chose, the sky was one cloud. The housemaid entered through the servants’ gate at the regular hour, in her regular shoes, with the grocery bag she always brought. I waited with Quang in the jasmine-shadowed alley where the brick wall behind the house bulged like a bad memory. She slid a thin stack of folders from a false bottom in a wood crate in the toolshed and passed them through the slats to Quang.

A voice cracked the yard open like thunder.

“What do you think you’re doing?”

My body froze. Quang’s didn’t. He tucked the files under his arm, grabbed my wrist, and pulled me into a run.

Behind us, the yard turned into a brawl of sound—footfalls, a shout choked with rage, a woman’s voice raised for the first time in thirty years. “Enough!” I heard a thud, a part of a word, a breath turning into a cry.

I twisted to go back. Quang yanked me forward. “This is your chance,” he hissed. “Take it. She knew what she was doing.”

We ran to the nearest police station. Bright lights. A yawning officer who didn’t want to be yawning anymore. I spilled. The officer looked as if he had been handed the wrong form. Then Quang turned on the recorder and slid the folders across the desk.

Paper makes a different sound when it’s heavy with other people’s blood. The officer turned a page. Another. A third. He picked up his phone. He stopped yawning.

By morning, my husband’s family had lawyers in their lobby and their own names in reports. By afternoon, men who had never been told “no” learned to hear it. That night, my head hit a pillow and actually slept.

Later, after doctors stitched a small tear in her scalp and she made the young nurse roll her eyes by asking for tea and sugar, the housemaid took my hands on the hospital bench. “Don’t say ‘I owe you,’” she said. “Debts make people behave like the ones we just left. Just live. That’s the return I want.”

Quang drove me back to the edge of the city. The fields were all shadow and cricket. “You’ll need a new place,” he said. “New name. Money.” He looked at my old phone. “New number.”

“I know,” I said. I did.

He shifted on the bike. “They will get years,” he said. “Not enough years. Men like that keep years in their pockets and hand them out later like gifts. But it will be some years.”

“Some years,” I echoed. “It’s a start.”

He looked away. “Don’t waste them.”

If you’ve never disappeared, let me tell you what it feels like. It is both less dramatic and more exhausting than you think. There is no single door you step through, no costume you shrug off and replace with a new life. There is instead a series of small swaps—a name on a bill; a landlord who asks fewer questions than the last one; a haircut that makes your reflection pause; a coworker who starts to recognize your voice; a grocery shop where the woman at the till remembers whether you like your greens wrapped separately. Disappearing is work. So is reappearing as someone no one’s looking for.

I learned the new bus routes before I learned the new streets. I found a tailor shop with a “help wanted” sign and a boss who spoke three languages and cared most about whether hems are even. On Saturdays, I took online classes in bookkeeping—how to make columns hold together. I ironed out numbers the way I ironed out seams. It calmed me to stack the world in clean lines.

I called my mother when the fear could bear it. We used code that we hadn’t agreed on: “I’m watering the plants” meant “I’m eating”; “the cat ran out again” meant “I had to move.” She asked fewer questions than silence did. Bless the old women of the neighborhood; they taught her how to lie less like a saint and more like a lioness. “I don’t know where she is,” she told whoever asked. It had the advantage of being true.

A woman from the charity office brought food one morning and left it on the stoop. The box had sticky rice and pickled vegetables and a piece of paper with a phone number. “When you’re ready,” she’d scrawled in block letters. It took me six weeks, but I called her. I didn’t tell her my story. I told her that I could do math.

“What kind?” she said.

“The kind that keeps books out of trouble,” I said.

She hired me for afternoons. I made chaos make sense. It felt like standing on a solid floor after a storm.

News trickled in from a friend of Quang’s cousin’s neighbor. The old house was for sale. The portraits had been taken down and stacked against a wall. No one wanted to buy a museum of other people’s sins. The papers wrote about “illegal lending rings” and “predatory contracts” and used words like “alleged” that tasted like stale bread. But people were charged. Some pled. Some fought and lost. Some fought and won in ways that looked like losing to anyone with eyes.

On the day of the sentencing, I bought a second-hand rug and didn’t think about them. That is a sentence that feels simple to write and took a year to be true.

The mind does not undo itself on command. Even when your doors have new locks, your body thinks old footsteps are at them. Even when the only person in the next room is your cat, your ears hear the creak of someone else’s shoe. Some nights I dreamed of the dress under the bed, of silk that breathed like an animal. Other nights I dreamed of running and never arriving. I woke in the dark and practiced naming everything in the room. Lamp. Table. Fan. Shoe. Courage: the one thing you cannot point to but need most.

Courage, it turns out, can be learned.

I started to go to the community center at night, sitting in a circle with other women who had different faces and the same story. We talked about back doors and bank accounts and how the word “no” is a muscle you strengthen. We called each other by our first names. We brought pastries. We taught each other to breathe with one hand on our ribs and one hand on our belly. The first time I told my story from beginning to end, I did not shake. After, I slept without dreaming.

A small nonprofit began asking me to help other women put their documents in order. “You’re an organizer,” the director said. “You make a life out of pieces.” I did. I printed checklists: copies of IDs; photos of bruises; bank statements; names of contacts. I taught them the habit that saved me: write everything down. Paper doesn’t forget.

Sometimes the past called anyway. An unfamiliar number. A news alert. Once, a lawyer who wanted to talk about “restorative processes” and “closure.” I closed my eyes and imagined that white room where I’d once been trapped. “My closure,” I told him, “was the back door.” He didn’t understand. That was fine. Some sentences are just for you.

I saw the housemaid again on a bus. She was carrying a plant whose leaves had frayed in the sun. “I don’t know if I saved you or you saved me,” she said when we were both sitting down. “Maybe we saved each other.”

“Maybe we decided not to drown,” I said.

She laughed. “Same thing.”

People ask why I’m telling this now. Why didn’t I keep hiding? Because silence is a debt, and I paid enough.

I’m telling it because I want you to know that sometimes the softest knock is the loudest surface of love you will get. That you can jump into the dark and still land where the ground will hold. That quiet does not mean weak; that running can be a form of coming home to yourself. That the voice that says “Go straight. Don’t look back” can be your own, and, baby, when it is, listen.

They say some women step into their joy on their wedding night. I believe that. I also know some women step into a fight. Both can be a beginning. If you’re dreaming of the dress and feeling the weight of the hem catch around your ankles, if you hear footsteps in halls that were not built for you, if someone you don’t know whispers “now” through the door—leave.

I was lucky enough to have the knock. I was lucky enough to have courage when I hadn’t ever practiced it out loud. I was lucky to have a woman who had lived under other people’s names for too long and a man whose hands pulled me forward without asking me to be grateful.

I am luckier still to be the one telling this story, intact, a name on my own mailbox, a lamp I turn off myself, a door I open when I choose.

The rest of my life is not owed to what happened. It is owed to what didn’t. I didn’t stay. I didn’t die. I didn’t become a ghost in my own story.

What I became, instead, is precisely this: a woman who heard a soft knock, changed her clothes, and walked out the back door into the night. And kept walking until the night split open and made room for morning.

The city had a way of making even the biggest stories shrink to fit the day. After the raid, after the charges, after the headlines that thrummed for a week and then slid down the page like old weather, people still had to buy rice and wash uniforms and remember to pay the internet. I learned that redemption doesn’t arrive like a brass band; it shows up in little forms you fill out twice because the first copy gets wet.

It didn’t mean the noise stopped. Reporters knocked at doors and at the edges of my life, men and women with practiced soft faces and hard eyes. They learned my name without my permission and printed it once before a judge signed an order that made them use “the woman who fled” like a pronoun. The housemaid Sáu wouldn’t come in through the front of my new place—we’d met too many doors to trust them—but she sat at my table and drank the tea that stained cups and said, “If you talk, make it cost them something,” and that became the shape of any answer I gave.

An organization I hadn’t known the name of until they slid their card under my door—a NGO with a logo that looked like a horizon—sent a woman who wore jeans and had laugh lines that earned them. She sat without straightening my cushions and said, “We can do this two ways. Anonymous, where you tell me the facts and I turn them into pressure. Or public, where you own it so hard that their lawyers can’t pry it off you.” She looked at my hands when she said it, not my eyes, as if to tell me she wasn’t going to put words into my mouth. “You don’t have to decide today,” she added, and that mattered more than all her acronyms.

I didn’t go on television. I didn’t sit under the cold lights and let a stranger say my name if I couldn’t even say it comfortably in my own bathroom yet. But I said yes to something else—a training session where I sat in the back of a room that smelled like dry-erase marker and told twenty women about bank accounts and photocopies and exit bags, about the way a story as small as your own can be a sharp instrument if you hold it correctly. The first time I said “back door” out loud in a room of strangers, my throat went dry. The second time, someone else said it first, and I nodded and didn’t teach the word to anyone; it was already theirs.

The wealthier among them—women who wore rings they found heavy and had drivers whose eyes in rearview mirrors were worse than fire alarms—told me the ways men who owned everything tried to own the air too. The poorest among them—housemaids who counted beds with their fingers every morning and folded sheets that smelled of money and perfume—told me how secrets travel under doors and down sink drains. If you’ve never been in a room where a plan is born out of the math of survival, let me tell you what it feels like: like a heart learning to run after a long fever. Ragged at first. Then regular. Then hungry for distance.

The courtrooms were brighter than I expected and dirtier at their feet. You can see years of people if you’re brave enough to look: scuffs where chairs got kicked back, ink ghosts on walls where someone lean-shouldered bumped their head into the plaster and left their oil. On the day I testified, my mouth tasted like copper. My palms were dry. I had looked in the mirror that morning and said the things I wanted to say not like a rehearsal, but like a blessing spoken over old wounds. “The first time someone warned me,” I told the judge, “she didn’t raise her voice and she didn’t perform. She knocked. Quiet. And all my noise heard it. That kind of warning should be illegal to ignore.”

The lawyers made noises with their mouths like they had read a book about how to talk to a woman who had decided not to be a story anymore. I said the young woman’s name—the one who didn’t walk out of that house. I said it like the syllables were a strange fruit I’d learned to love. I watched a man who always sits in his chair and makes other people stand up to talk swallow his Adam’s apple like it had hurt him for the first time. I watched the judge hold my eyes longer than she had to and then write something down like she’d been waiting to write it for a while.

The sentences passed like sandbags at a flood. They were not enough; they were, for once, not nothing. Men went away in vans that smelt like vinyl and old rain, and others had to sit at tables and tell accountants what a number was just like. The estate went dark and then lit up again with real estate agents stage-whispering “opportunity.” The portraits came down. A rumor passed that the house would become a “wellness center,” the kind of rebranding rich men do when they don’t want to call a place what it is. It didn’t. No one could buy it without tasting the line of its history every time they swallowed.

It was Quang, brusque as always, who said, “You know, we could do it.” He said it while we were standing on the street where the jasmine had learned to climb again in my absence. We weren’t there for the house. Sáu wanted to show me the hole in the wall where the gardener used to hide the good shears, and where she had hidden the spare key in a jar like a joke. “If it belongs to nobody,” she’d said, “it will be everybody’s again. That’s dangerous.” She rarely issued judgments. When she did, they fell like coins that had waited for the right slot.

“We don’t need it,” I said, because I didn’t want to build a shrine.

“The building doesn’t matter,” Quang said. “The door does.”

We didn’t make a shelter out of my old fear. We built a network that made old doors behave themselves everywhere else. There were five addresses at first: one in the north side of the city, behind a noodle shop; one tucked into a block of old shops where a line for bánh bao hid women waiting for legal help; one with a back gate that took a push because its hinge was stubborn like an aunt; two in suburbs with the kind of trees that make roads look older than TV. We called them Nhà Sáu—House of Six—because the woman who saved me had a name that doubled as a number in a language that likes to hide its gifts in multiplicity.

“Oh, no,” she said when she saw the sign for the first time. “Now people will think I am big.”

“You are,” I told her. “You always were. You just lived small because someone decided a housemaid’s size should fit a closet.”

She did not like the fuss. She did like the tea. She came to the opening and told the volunteers where to put the towels and how many spare keys a good house needs to hide, and where not to hide them because certain men look for them there.

A woman came the first night and knocked like she’d practiced in her imagination and was afraid she would get it wrong. A teenager with a baby on her hip and a face so set you would have thought she was doing math instead of measuring survival. When we opened the door, she looked past us like she expected to have to negotiate with ghosts. “Do you have three hours?” she asked. “I need to make a plan before he checks the meter again.” We didn’t ask “who.” We put water in her hand and a pad of paper on the table and called two people who were already halfway to their scooters before the phone hit their pocket.

The day it truly became a thing—bigger than me, bigger than the house, bigger even than the headlines—was not in a room with donors or flowers. It was a Saturday in September when the Metro failed between stations and four women from four different stops texted the same number and a volunteer watched the rail map and sent cars like chess pieces. “All done,” she wrote at midnight, the kind of “done” that means “for now,” the kind of “now” that means “we will be here again tomorrow.” I printed the message and stuck it on the corkboard above the calendar because I was, at my core, a person who liked to pin accomplishments.

Sometimes the old life flickered into the new one like bad TV. I saw my almost mother-in-law at a temple one morning, barefoot on the cool tiles, the incense a slow river at her chest. She looked smaller, though I couldn’t trust my eyes because sorrow shrinks some people only in the way you notice if you’ve memorized their old shape. We stood near the same bowl of oranges and pretended to eat time. She saw me before I saw her seeing, which is the only way a meeting like that works. She lifted her palms and pressed them together and dipped her head the barest amount, as if she were asking a favor she had no right to. I did not dip mine back. I did not walk away. I stood still long enough for us both to feel our ages. She came closer, careful like a deer.

“Do you hate me?” she asked without hello. It is a brutal gift when someone refuses to play the game of small doors.

“No,” I said, and meant it. “Hate makes the house hot.” I held the answer away from her like a dish with steam. “Do I trust you? No. Does it matter? Only for the past. This is the future’s temple. Leave something here that is not a memory.” I gestured to the donation box. She put money in reluctantly like it embarrassed her to have numbers in her hand that couldn’t end arguments.

“I was a girl once,” she said, not in defense, just as a fact. “Then I learned the only way to live with a man like that is to call the sky a ceiling and to stay warm underneath it.”

“There are other houses,” I said. “We already knew how to build them. We weren’t allowed to gather the wood.”

She nodded like a woman who has come to a mathematics she cannot solve and set her hand on the stone lion and said his name—her son—as a mother says the name of her child even when that child has knocked holes in her life. I let her have it. Names aren’t property. They are debts. You only pay yours when you have something worth buying.

The day we dedicated the first Nhà Sáu to its work, an old brown dog wandered in and lay down in the exact wrong place and snored through the speech I had written at midnight and decided not to read at dawn. It felt right. Women who couldn’t save themselves with words were being saved with a nap. Quang grilled pork in the alley like he was auditioning for a job he did not want. Volunteers arrived and leaned on brooms and made plans to fix the hinge. In the corner, near a shelf with neatly folded towels and new toothbrushes, a little plaque hung crooked because no matter how you try you cannot escape sentiment entirely.

We do not owe you our story. We owe you the door.

I can’t tell you about all the women who crossed those thresholds. There are laws that prevent it and instincts that forbid it. I can tell you about the curious sound a room makes when someone realizes she is not in danger anymore. It’s not silence. It’s a kind of negative breath, an exhale that never learned how to forget itself. I can tell you that the loudest laughs come from kitchens in houses like that. I can tell you I have never been more proud of a receipt than the one for a sixty-rupee pair of flip-flops purchased at nine p.m. because a woman had come in barefoot.

Some nights, when the phone didn’t ring and fear slept in someone else’s bed, I sat with the housemaid on the concrete steps of the old shed and we counted stars to prove to ourselves they were still there. She got sick in a slow, competent way, folding her days to fit the ache. We took turns pretending not to worry. When the hemorrhage made itself known, she scolded the doctor who didn’t scold easily. “Don’t you have other patients who need fussing?” she asked. The man smiled because some women permit only themselves the privilege of being stern.

She asked me to promise two things if she left before the ink dried on all our paperwork. “Don’t let them give me a speech,” she said first. “Make them clean something instead. The floor, at least.” I promised. “And keep your name. Or make a bigger one. Don’t let your life be the thing that happened to you. Make it be what you did next.” I put my forehead to hers because we had found no other way to say goodbye. “Yes,” I whispered. “On my face, yes.”

When she died, five women scrubbed the floor at Nhà Sáu on their knees although every joint in their bodies knew better. They burned incense and told her stories out loud like she had been gone for a week-long errand and would be back by supper. We cooked, and then when no one could eat, we packed into boxes and sent the boxes out with the same speed we used on nights when fear ran faster than us. We put her name on a piece of paper at the temple and wrote it thick and then subscribed to the only ritual that has never failed: we went back to work.

Quang kept coming around, showing up in the doorway with tools and a bag of vegetables and a bad joke he did not tell because he saved humor like money. I learned that he talked as little as possible on purpose because the things he had seen in his work would rot your mouth if you let them in too often. He took me once, on a Tuesday so bright it hurt, to the mechanic shop where his uncle taught him how to rebuild wreckage until it ran again. “That’s all I’m doing,” he said. “With people. With doors. With engines.” He opened my palm and put a key in it. “For the gate,” he said, and it fit the lock like it had been waiting.

We never called what grew between us romance, because the word felt like the dress under the bed—too much fabric, too many pins. What we built was something else. We built a porch on a house that had a good roof; we built a second bowl when we made soup; we learned each other’s silences and respected them like parentheses. Sometimes he put his hand on the small of my back in a crowded room and it felt like being seen without being expected to perform. Sometimes I put my hand over his on the gearshift and he took a breath like he hadn’t realized he’d been holding it for an entire decade. We did not owe anyone a story about it. We owed ourselves the door.

The soft knock came back to me one night not as a memory but as a sound repeated. I was sitting at the desk at Nhà Sáu number three, adding up the donations we owed a receipt for, when it tapped at the frame itself—gentle, like the bones held manners. I opened the door and there she stood: a woman in a dress that still had the mark of a steamer iron, lipstick that had held until it didn’t, eyes that had already learned the emergency exit. The first sentence strained against her teeth but got out anyway. “If I don’t go now, I never will.” She looked beyond me, past the table and the couch and the shelf of towels, as if expecting her future to be as rude as her past.

“Leave the shoes,” I said, because some commands give you something to do so your hands don’t tremble. She stepped out of them, an act that was both practical and holy. She crossed the threshold and the room changed temperature.

“What will happen to him?” she asked, meaning the man.

“What always happens to men like that,” I said. “They find a way to call their ruin someone else’s revenge. You can’t fix their story. You can only write yours.”

I gave her water and late-night rice and a blanket, because salvation sometimes looks like carbs and cotton. I gave her a toothbrush because no one thinks to pack one when survival is a sprint. I gave her the sentence I had been given—the one I had tucked inside my cheek until it dissolved into a habit.

“You’re safe for now,” I said. “Tomorrow we’ll make the plan.”

She took a breath and let it out in a length that made me feel like the house was holding her lungs. She looked at the plaque on the wall and read it silently. She did not cry. She put her hands flat on the table and lined her clean fingers up with a straight edge like she was measuring the right way to behave in a new life. “I don’t want to tell you everything,” she said, ashamed for half a second.

“You don’t have to,” I said. “We’re not owed your story. We’re entrusted with your door.”

Outside, it started to rain—a steady, clean fall that sounded like tea and old promises and the roofs of houses that remember the names of the women who left them. Inside, the kettle rattled the burner. The woman turned her head as if listening to a noise she recognized. I reached for another cup. We sat on either side of the table and let the steam fog the window. I told her about the morning I ran. She told me about the dress she had left under the bed. We decided how the night would go from here. The small house held both our laughters like it had been built for that purpose.

Later, after she slept, I walked out to the porch, where the smell of the wet garden rose like a song. Quang leaned against the post. He didn’t knock because he had already learned to sit with his quiet in a way that didn’t press on mine. We watched the street as if there were something to see.

“You remember the first ride?” he asked, meaning the night we were a bullet out of a dangerous story.

“I always will,” I said. “It taught me how to get low when the wind decides to teach you a lesson.”

He nodded and flicked ash off the end of a cigarette he shouldn’t have lit and then did because he is a human, not a protagonist. “It’s funny,” he said, and I cut my eyes at him because he rarely tried to be. “All that money, those halls, those steps that echo in the wrong places. All that power. And the thing that undid it began with a knock softer than a bird.”

“What’s funny,” I said, “is that you still call that funny.”

He huffed something like a laugh. “The rain’s good,” he said, looking up.

“It’s the kind that leaves the air better than it found it,” I agreed.

We stood then, under the slow drumming, two people who had taken on the work of doors. Behind us, inside a house we’d named for a woman who used to iron shirts and fold shame into corners so it wouldn’t show, a person slept with her shoes off and her future on the table in the form of a list. Before us, the street shone like a thing that had been cleaned. The night was not safe; nights don’t make promises they can’t keep. But in that small square of illuminated rain and old cement, it felt like the world was learning, at least in the places we could reach, the difference between a lock and a life.

Morning would come as it always does: late for some, early for others. There would be patrol cars and paperwork and passwords to change and a mother to call with a voice that steadied by sentence three. There would be a room of women who clap maybe once when she walks in and then hand her a pen. There would be laws we’d fight, again, and again, because power doesn’t sleep and someone will always be making a rule in a room where we are not invited. There would be rice to cook. There would be letters to fold. There would be laughter that fixes a hinge better than nails.

And there would always, always, be the knock—soft, then louder, then echoing into other houses where women have learned to keep towels on a shelf and cups on a hook and lights that cannot be seen from the street. It would travel, as sound does, through the bones of a building and into the bones of a life, telling anyone who can hear it that it is time. That it has been time. That we do not owe anyone a spectacle. We owe ourselves a door.

I locked up, the key warm from my hand. I went inside and turned off one lamp, then left the one over the table on because it’s easier to sleep if you know where to go when you wake in the dark. I lay down on the old couch with its polite springs and listened to the rain run its course. In the morning, I would boil water for three cups, maybe four, depending on how long she slept. I would put paper on the table. I would write the first item at the top of a list without asking permission from anyone: You are here.

News

A little girl calls 911 and says: “It was my dad and his friend” — the truth brings everyone to tears… gl

Emergency operator Vanessa Gómez had answered thousands of calls in her 15 years at the Pinos Verdes County Emergency Center….

A little girl calls 911 and says: “It was my dad and his friend” — the truth brings everyone to tears… djh

Emergency operator Vanessa Gómez had answered thousands of calls in her 15 years at the Pinos Verdes County Emergency Center….

After my husband’s funeral, my son drove me to the edge of town and said, “This is where you get out.” gl

After my husband’s funeral, my son said, “Get out,” but he had no idea what I had already done. You…

After my husband’s funeral, my son drove me to the edge of town and said, “This is where you get out.” djh

After my husband’s funeral, my son said, “Get out,” but he had no idea what I had already done. You…

Billionaire CEO Sees His Ex-Girlfriend Waiting for an Uber With Three Kids—All Three Identical to Him gl

Billionaire businessman Julián Castañeda had just stepped out of yet another endless meeting in Polanco—one of those rooms where everyone…

Billionaire CEO Sees His Ex-Girlfriend Waiting for an Uber With Three Kids—All Three Identical to Him djh

Billionaire businessman Julián Castañeda had just stepped out of yet another endless meeting in Polanco—one of those rooms where everyone…

End of content

No more pages to load