July 1st, 1944. Halandia Air Base, New Guinea. 4 P38. Lightning’s touchdown after 6 and 1/2 hours over enemy territory. Three pilots climb out with fuel gauges reading nearly empty. Maybe 50 gallons left in their tanks. The fourth aircraft flown by a 42-year-old civilian still shows 210 gall remaining.

Same mission, same weather, same airplane. But somehow this pilot used 200 gallons less fuel than the best fighter pilots in the Pacific. The ground crew chief stares at his fuel stick, then checks it again. For months, American pilots had been flying these twin engine fighters exactly as the manual demanded.

2200 RPM autorich mixture settings following every procedure drilled into them since flight school. They’d been taught that deviating from these standards would destroy their engines. That running over square, high manifold pressure with low RPM, was aviation suicide. But standing on that New Guinea air strip, watching fuel readings that defied everything the Army Air Forces believed about engine management, one question hung in the humid Pacific air. What if everything they’d been taught about flying was wrong? The checker game had been going

on for 20 minutes when the knock came at the screen door. Colonel Charles Macdonald barely glanced up from the red and black squares, his mind still calculating moves while the afternoon heat pressed down on their makeshift headquarters at Helandia Air Base.

Lieutenant Colonel Merryill Smith sat across from him, equally absorbed in their improvised entertainment, one of the few diversions available in this corner of Netherlands New Guinea. Excuse me, gentlemen. The voice carried a quiet authority that made Macdonald finally look toward the doorway. A middle-aged man in navy khakis stood there, his uniform crisp despite the humidity.

I’m Charles Lindberg. Macdonald’s hand froze halfway to a checkerpiece. The name hung in the air like smoke from a crashed aircraft. Smith’s eyes widened slightly, but Macdonald found himself staring at this unremarkable looking civilian, trying to reconcile the legend with the man standing before them. “That Charles Lindberg, the one who flew solo to Paris 17 years ago.

” “General Hutchinson sent me,” Lindberg continued, stepping into their cramped quarters. “He thought I might be able to discuss P38 combat operations with you.” Macdonald stood slowly, the checker game forgotten. At 29, he commanded the 475th Fighter Group, but he’d grown up reading about Lindberg’s Atlantic crossing.

Every pilot in America had the spirit of St. Louis was more than aviation history. It was the moment flying transformed from circus stunts to genuine transportation. And now that same pilot was standing in their tent, asking about their daily reality of flying missions across the vast Pacific. Of course, Mr. Lindberg, please sit down.

Macdonald gestured toward a folding chair, then called for Colonel Warren Lewis. If they were going to discuss P38 operations, Lewis needed to be here. The commanding officer of the 433rd Fighter Squadron knew better than anyone the crushing mathematics of their current situation.

Lewis arrived within minutes, his flight suit still damp with sweat from the morning’s briefing session. He took one look at their visitor, and his professional composure cracked slightly. Mr. Lindberg, what brings you to our little corner of Paradise? The irony wasn’t lost on any of them. Paradise? If Paradise consisted of metal hangers baking under tropical sun, mud that never quite dried, and the constant buzz of insects that seemed immune to every repellent the quartermaster could provide. But Lewis’s question was genuine.

What could the most famous aviator in the world want with their fighter operations? I’m here to learn, Lindberg replied simply. And perhaps to share some observations about long range flying. Lewis settled into another folding chair, and Macdonald could see him mentally shifting into briefing mode. Well, Mr.

Lindberg, our situation is pretty straightforward. We’re flying missions that push every limit these aircraft have. The colonel pulled out a worn map, spreading it across McDonald’s desk and pushing the checkerboard aside. His finger traced routes across hundreds of miles of blue Pacific water, dotted with tiny islands that looked insignificant on paper, but represented life or death navigation points for pilots flying alone over endless ocean.

6 and 12 to 7 hours,” Lewis continued, his voice taking on the measured tone of someone who’d calculated these numbers too many times. “That’s what we’re asking of these boys now. Missions that were impossible a year ago are becoming routine, and the fuel margins.” He shook his head. Macdonald watched Lindberg study the map with the intensity of an engineer examining blueprints.

Those pale blue eyes moved systematically from island to island, calculating distances with the precision of someone who’d spent decades thinking about range and endurance. It was the look of a pilot who understood that fuel wasn’t just a number on a gauge. It was time, distance, and ultimately survival. The P38L has a published combat radius of 570 mi.

Lewis explained, “In practice, we’re pushing that envelope every single mission. Standard procedure calls for 2200 to 2400 RPM autorich mixture settings. Fuel consumption runs over 100 gall per hour total.” Lindberg nodded slowly, but Macdonald caught something in his expression. Not confusion, but recognition. Like a mechanic hearing symptoms he’d diagnosed before.

These boys come back exhausted, Lewis continued. 7 hours in that cockpit is torture. Sitting on a parachute, emergency raft and ore. The physical strain is one thing, but the mental pressure, he gestured toward the map again. Every mission brief becomes a fuel calculation. How much reserve? How long can we stay over target? What’s our absolute point of no return? Macdonald had seen that pressure firsthand.

Young pilots, some barely 21, hunched over flight planning tables with slide rules and pencils, calculating margins that determined whether they’d see another sunrise. Too many good men had already been lost to empty tanks rather than enemy bullets.

The mathematics were unforgiving, run out of fuel over the Pacific, and rescue was unlikely at best. And it’s getting worse, Lewis added quietly. The targets keep getting farther away. Rabal Waywok. Now we’re talking about missions deep into the Philippines. The war is moving west, but our fuel capacity isn’t growing with it. Lindberg listened without interrupting, occasionally asking questions about mixture settings, propeller pitch, or cruise altitudes.

His queries were specific, technical, and revealed a depth of knowledge about aircraft systems that surprised Macdonald. This wasn’t just a famous name asking polite questions. This was a pilot who understood power plant management at a level most combat flyers never reached. “Have you experimented with different cruise settings?” Lindberg asked finally.

Lewis and Macdonald exchanged glances. “The technical orders are pretty specific,” Lewis replied carefully. “We follow standard procedures for engine management. High RPM, rich mixtures. That’s what keeps these Allison’s running.” Something in Lindberg’s expression shifted almost imperceptibly. Not disagreement exactly, but the look of someone who’d heard conventional wisdom that didn’t match his experience.

Mr. Lindberg, Macdonald said slowly. You mentioned observations about long range flying. What kind of observations? For the first time since entering their quarters, Lindberg smiled slightly. Would you be interested in a practical demonstration? I checked out in the P38 a few days ago, flying Dick Bong’s old aircraft to the base. I’d like to join one of your combat missions.

The request hung in the humid air between them. Macdonald felt the weight of command settling on his shoulders. Taking a civilian, even Charles Lindberg on combat operations carried risks that went far beyond normal mission parameters. But something in the man’s quiet confidence suggested this wasn’t idle curiosity.

What did you have in mind?” Macdonald asked. The recreation hall at Holandia had seen better days, though Macdonald couldn’t remember when. Dirt floors packed hard by months of foot traffic, palm thatch roof that leaked during the afternoon rains, and a single ping-pong table that served as the squadron’s primary entertainment when they weren’t flying missions or maintaining aircraft.

Unshaded light bulbs hung from the rafters, casting harsh shadows that made every face look older and more tired than it should. Macdonald stood near the makeshift podium, really just a wooden crate turned on its end, and surveyed the assembled pilots of the 475th Fighter Group. 43 men, most under 25, all wearing the thousand-y stare that came from too many hours over hostile territory with fuel gauges constantly in mind.

Some perched on folding chairs, liberated from various supply dumps. Others sat cross-legged on the floor, and a few leaned against the walls with their arms crossed. “Gentlemen,” Macdonald began, his voice cutting through the low murmur of conversation. “Mr. Lindberg has something he wants to share about extending our range capabilities.

” Lindberg stepped forward with the measured confidence of someone accustomed to addressing skeptical audiences. He wore the same Navy khakis from their meeting 2 days earlier. Though now Macdonald noticed the small details that marked him as different from standard military issue. The civilian watch, the absence of regulation insignia, the way he moved with the unconscious grace of someone who’d spent decades around aircraft.

Reduce your standard 2200 RPM to600, Lindberg said without preamble. No warm-up, no context, just the technical specification that would either save lives or destroy engines. Set fuel mixtures to autolean instead of autorich. Increase manifold pressures slightly to compensate. The silence that followed was the kind Macdonald had heard before.

Not confusion, but the mental grinding of pilots trying to reconcile what they’d just heard with everything they’d been taught. Lieutenant Bobby Johnson, one of their steadiest formation leaders, raised his hand tentatively. “Sir, are you saying we can cut RPM down to,400 and use 30 in of mercury manifold pressure?” “That’s correct,” Lindberg replied.

“The fuel savings run between 50 and 100 g per mission, depending on conditions and flight duration.” The silence deepened. Macdonald watched his pilots faces, reading the mix of hope and horror playing across their features. Hope because longer range meant better survival odds, more tactical flexibility, and the ability to reach targets that had been beyond their grasp.

Horror because every flight instructor, every technical manual, every engine school had taught them the same fundamental principle. Never run over square. Captain Jim Watkins voiced what everyone was thinking. Mr. Lindberg, that’s going to burn up our engines. We’ve always been told that low RPM with high manifold pressure causes detonation. You’ve been told wrong, Lindberg interrupted, his voice carrying the quiet authority of absolute certainty.

The technique works because you’re maintaining high manifold pressure while backing off RPM, not running both high simultaneously. Combined with autolean mixture settings instead of autorich, this reduces fuel consumption to approximately 70 gall per hour total. Lieutenant Thomas Hayes, barely 22 and still carrying the eager intensity of someone who’d graduated flight school 6 months earlier, did the mathematics aloud.

70 gall hour versus our current 100 plus. That’s almost a 30% reduction. More than that, Lindberg replied, “Flying at 185 mph indicated air speed, this technique provides roughly 2.6 m per gallon. Your combat radius extends from 570 mi to 700, possibly 750 mi, depending on conditions.” The numbers hung in the humid air like artillery shells waiting to detonate.

Macdonald could see his pilots running calculations, trying to grasp what those figures meant in practical terms. 750 mi combat radius translated to missions they’d previously considered impossible. Deep strikes into Japanese-held territory that had been beyond their fuel envelope.

But the resistance ran deeper than simple mathematics. These men had survived combat by following procedures that kept their engines running and their aircraft flying. The Allison V1710 engines in their P38s were finicky enough under normal conditions. Tampering with established crew settings felt like gambling with their lives. Sir, said Major Pete Peterson, a veteran of missions over Rabal, who’d earned his skepticism through hard experience.

Every technical order we’ve seen warns against over square operation, the risk of engine knock, piston damage. The procedure appears controversial because you’ve been trained to believe it would damage engines, Lindberg replied patiently. But consider the source of that training. How many of your instructors had experience with sustained longrange cruise flight? How many had operated these specific power plants under extended endurance conditions? The question cut to the heart of their dilemma.

Military flight training focused on combat maneuvering, formation flying, and gunnery. Not the kind of efficient longrange cruise techniques that Lindberg had perfected during his decades of civilian aviation. The technical orders were written by engineers who prioritized engine longevity over operational range, assuming that fuel capacity rather than consumption would determine mission limits.

Lieutenant Colonel Smith, who’d been silent during Lindberg’s explanation, finally spoke up. Mr. Lindberg, you’re asking us to fly 9-hour missions. 7 hours in a lightning cockpit is already torture. sitting on emergency equipment, dealing with oxygen system quirks, fighting fatigue that affects judgment. He gestured toward the assembled pilots.

Nine hours seems beyond human endurance. Macdonald nodded grimly. The physical challenges were real and couldn’t be dismissed. P38 cockpits were cramped under the best circumstances, and long missions meant sitting on parachutes, emergency rafts, and survival gear for hours at a time.

Oxygen masks became increasingly uncomfortable. Radio headsets caused pressure points. And the mental strain of navigation over featureless ocean wore down even experienced pilots. The endurance challenge is legitimate, Lindberg acknowledged. But consider the alternative. How many pilots have you lost to fuel starvation? How many missions have been aborted because fuel margins didn’t allow sufficient time over target? The question struck home because every pilot in the room knew the answers.

Too many good men had disappeared over the Pacific, their aircraft simply vanishing when fuel ran out hundreds of miles from land. Others had been forced to turn back short of their targets, allowing enemy installations to remain operational for lack of sufficient fuel to complete attacks.

The choice isn’t between comfort and discomfort, Lindberg continued quietly. It’s between proven techniques that extend your operational capability and conventional methods that may be limiting your effectiveness unnecessarily. Macdonald studied the faces around him, reading the mixture of curiosity and concern in their expressions.

These were combat veterans who’d learned to trust their equipment and their training, but they were also pragmatists who understood that survival often depended on adapting to new information. Mr. Lindberg Macdonald said finally, “Would you be willing to demonstrate this technique on an actual combat mission?” The morning of July 3rd dawned clear over Hollandia with visibility stretching to the horizon for the first time in a week.

Macdonald stood beside his P38 Lightning at 0530, watching ground crews complete their pre-flight inspections while the tropical air still carried the relative coolness of night. Today’s mission would test everything Lindberg had claimed about fuel management. A 1280 mi round trip that would push even conventional fuel planning to its absolute limits.

Lindberg emerged from the operations tent carrying his flight gear with the deliberate movements of someone who’d performed this ritual thousands of times. His borrowed flight suit fit reasonably well, though Macdonald noticed he wore civilian flying boots instead of standard military issue.

More telling was the ease with which he handled his equipment, parachute harness, May West life jacket, oxygen mask, and survival kit arranged with the efficiency of long practice. Weather looks good for the demonstration, Lindberg observed, glancing toward the eastern horizon, where the sun was beginning to burn off the overnight haze.

Visibility should remain clear for navigation, and winds are minimal. Macdonald nodded, though his attention was focused on the fuel calculations. He’d run three times during the night. Standard cruise settings would require every drop of internal fuel capacity with virtually no reserve for combat maneuvering or unexpected headwinds. If Lindberg’s technique failed to deliver the promised savings, they’d be calculating glide ratios over open ocean.

“Tommy’s flying your wing today,” Macdonald said, indicating where Major Thomas Maguire was completing his own pre-flight inspection two aircraft down the flight line. He’ll be watching your fuel consumption closely. Maguire looked up at the mention of his name, offering a brief wave.

America’s second highest scoring ace had volunteered for this mission specifically to observe Lindberg’s methods under combat conditions. If the fuel management technique worked for someone with Meguire’s aggressive flying style, it would work for anyone in the squadron. The briefing had been straightforward.

patrol sectors northeast of their current position with possible ground attack opportunities against Japanese supply installations on several small islands. Nothing extraordinary by their recent standards, but the distance involved would test both fuel efficiency and human endurance. Lindberg climbed into his cockpit with practiced efficiency, his movements economical and precise.

Macdonald watched him run through his checklist, noting that the civilian pilot took extra time with fuel system configurations. Unlike standard military procedure, Lindberg adjusted his mixture controls to autolean settings before engine start, and his propeller controls were set for lower RPM than any P38 pilot had been trained to use.

Engine start proceeded normally, both Allison V1710s coming to life with their characteristic wine as turbo superchargers spooled up to operating speed. But once taxi clearance came through, Macdonald noticed the difference immediately. Lindberg’s engines ran noticeably quieter than standard settings, their exhaust note deeper and less aggressive.

Alandia tower lightning flight requesting takeoff clearance. Macdonald transmitted. Lightning flight cleared for takeoff. Runway 27. Windcomm visibility unlimited. The four P38s lifted off in formation, climbing steadily through 3,000 ft as they headed northeast toward their patrol area.

Macdonald kept his throttles and mixture controls at regulation settings while maintaining visual contact with Lindberg’s aircraft flying on his right wing. Even during climb, he could see that Lindberg’s engines appeared to be developing identical power despite their different configurations. At cruise altitude, the demonstration began in earnest.

Lindberg’s voice came through the radio with technical precision. Reducing RPM to 1600, manifold pressure 30 in, mixture autolean, air speed 185 indicated. Macdonald cross-cheed his own instruments. His aircraft was consuming fuel at the expected rate, approximately 52 gall per hour per engine, or 104 total, but visual observation suggested Lindberg’s aircraft was maintaining identical air speed and altitude despite its radically different engine settings.

The first hour passed uneventfully, with navigation proceeding exactly as planned. Macdonald found himself checking fuel flow instruments more frequently than usual, comparing his consumption rates against mission planning calculations.

Everything matched expected performance, which made Lindberg’s claim seem increasingly significant. If the civilian pilot was actually achieving 30% fuel savings while maintaining cruise performance, the implications for Pacific operations were staggering. Maguire’s voice broke radio silence at the 1 hour 30 minute mark. lead. I’m showing fuel flow approximately 20% below normal for this phase of flight.

The transmission confirmed what Macdonald had begun to suspect. Even Maguire, flying standard cruise settings, but observing Lindberg’s technique closely, was unconsciously adopting more efficient power management. The psychological effect of watching fuel conservation in action was influencing flying habits across the formation. 2 hours into the mission, they encountered their first tactical situation.

Intelligence reports had indicated possible Japanese barge traffic near Samate Island, and visual reconnaissance confirmed several targets anchored in a protected cove. Standard attack procedure called for high-speed passes with full power settings. Exactly the kind of fuelintensive maneuvering that made long range missions problematic.

Lightning flight. This is lead. Target area ahead. Prepare for ground attack. Macdonald pushed his throttles forward, feeling both engines respond with increased power as fuel flow jumped to maximum combat settings. The attack run proceeded normally, diving approaches, multiple strafing passes, and defensive maneuvering to avoid anti-aircraft fire, but he noticed that Lindberg maintained formation throughout the engagement.

His aircraft responding normally to combat power demands despite its unconventional cruise configuration. The engagement lasted 12 minutes with all four aircraft expending significant ammunition against barges and shore installations. During the climb back to cruise altitude, Macdonald reset his engines to standard longrange settings while monitoring fuel remaining.

Combat power had consumed fuel at expected rates, leaving him with approximately 60% capacity for the return flight. Lead fuel check. Macdonald transmitted. Two showing 60% remaining came Maguire’s reply. 3 58%. 4 72% remaining. Lindberg reported quietly. Macdonald double-ch checked his radio, certain he’d misheard the transmission.

72%. After 2 hours of cruise flight and 12 minutes of combat maneuvering, Lindberg still had nearly 3/4 of his fuel load remaining. The numbers were impossible according to everything Macdonald understood about P38 fuel consumption for say again fuel remaining 72% confirmed Lindberg replied fuel flow during cruise has averaged approximately 70 gall per hour total the mathematics were undeniable while McDonald’s aircraft had consumed roughly 200 gall during the first phase of their mission Lindberg had used only 140 gall for identical distance and flight time.

The 30% reduction in consumption was exactly what he’d promised during the briefing, but seeing it demonstrated under combat conditions transformed theoretical possibilities into operational reality. The return flight provided additional confirmation.

Despite maintaining formation air speed and altitude, Lindberg’s fuel consumption remained consistently lower than standard cruise settings. By the time Helandia came into sight, Macdonald was calculating fuel margins that seemed almost luxurious compared to their normal tight planning. Landing revealed the full extent of the demonstration success.

Ground crews immediately began fuel measurements using calibrated dipsticks to determine exact consumption for each aircraft. Macdonald had returned with 18% fuel remaining, adequate for mission completion, but offering little reserve for unexpected circumstances. Lindberg climbed out of his cockpit with 34% fuel still in his tanks. The skepticism cracked first among the ground crews.

Technical Sergeant Mike Kowalsski had been working on P38 engines since before Pearl Harbor, and he understood fuel consumption the way a banker understood compound interest, through daily, meticulous observation of numbers that never lied. When Lindberg’s Lightning consistently returned from missions with fuel readings that defied every manual Kowalsski had studied, the veteran mechanic began asking questions that cut through military hierarchy.

Colonel Macdonald, sir, Kowalsski said after the fifth consecutive mission where Lindberg’s fuel consumption ran 30% below standard rates. Either this civilians got magic engines or everything we’ve been taught about cruise settings is wrong. Macdonald found himself nodding more frequently during these conversations.

The evidence was mounting with mathematical precision that couldn’t be dismissed or explained away. Mission after mission, Lindberg returned with fuel quantities that should have been impossible given the distances flown and time airborne. More significantly, his engines showed no signs of the damage that military doctrine insisted would result from over square operation.

The pilot’s resistance proved more stubborn than mechanical evidence. Lieutenant Hayes, who’d volunteered to try Lindberg’s technique on a training flight, returned from his first attempt, visibly shaken by the psychological pressure of running engines in configurations that contradicted everything he’d been taught.

“It felt wrong the entire time, sir,” he reported to Macdonald, like waiting for something to explode. But Hayes also reported fuel consumption that matched Lindberg’s claims almost exactly. 73 gall per hour total compared to his usual 100 plus gallon burn rate. The lieutenant’s fuel gauges didn’t care about his psychological comfort. They would simply recorded the mathematical reality of improved efficiency.

Major Peterson represented the old guard’s final stand against the new technique. A veteran of missions over heavily defended Japanese positions, Peterson had survived by following procedures that kept his aircraft flying when other pilots pushed their luck too far. “Mr. Lindberg,” he said during one particularly heated discussion in the operations tent.

“You’re asking us to bet our lives on techniques that go against everything we know about engine management.” Lindberg’s response carried the patient tone of someone accustomed to technical skepticism. Major, what you know about engine management comes from training designed for different operational requirements, short duration flights, maximum power settings, and conservative safety margins appropriate for training environments.

He gestured toward the mission planning board covered with routes that stretched hundreds of miles across empty ocean. These missions demand efficiency techniques that weren’t part of standard military curriculum. The breakthrough came during a mission to Weiwok on July 28th. Macdonald had planned the strike as a standard formation attack against Japanese supply installations, but intelligence reports suggested heavy fighter opposition.

The kind of extended air-to-air combat that would test every aspect of aircraft performance under the most demanding conditions possible. Lindberg flew on Meguire’s wing that day, positioning himself where the squadron’s most experienced combat pilot could observe his techniques during actual aerial combat. The mission profile called for a 400-mile transit to the target area, followed by potential air-to-air engagement, ground attack, and return flight.

Exactly the kind of complex operation where fuel management could mean the difference between mission success and disaster. They encountered Japanese aircraft exactly as intelligence had predicted. A formation of Mitsubishi K-51 dive bombers escorted by zero fighters approaching Waywok from the northwest.

The engagement began with standard tactics, altitude advantage, coordinated attacks, and aggressive maneuvering to gain firing positions. But as the dog fight extended beyond normal duration, fuel consumption became a critical factor for every pilot involved. Macdonald watched the aerial combat unfold with the detached precision of a commander who’d seen too many similar engagements.

P38s maneuvering against Japanese fighters in three-dimensional chess matches where split-second decisions determined survival. ammunition expenditure, fuel burn rates, and tactical positioning all factored into calculations that pilots made instinctively while pulling multiple G’s in combat turns.

The Japanese formation leader, later identified as Captain Saburro Shimatada, demonstrated the kind of aggressive flying that had made zero pilots legendary during the early war years. Shimata’s aircraft cut through defensive maneuvers with precision that suggested hundreds of combat hours, forcing American pilots to respond with maximum power settings that consumed fuel at rates far above cruise consumption.

Maguire’s voice crackled through the radio during a brief lull in the engagement. Multiple bandits, ammunition running low, fuel becoming a factor. It was the kind of situation that separated experienced combat pilots from those who hadn’t yet learned to manage multiple crisis factors simultaneously. Ammunition, fuel, enemy aircraft capabilities, distance to base, and weather conditions all demanded immediate evaluation while maintaining situational awareness in three-dimensional combat.

Lindberg’s aircraft maneuvered through the engagement with the same precise control he demonstrated during cruise flight. No wasted motion, no unnecessary power settings, and consistent tactical positioning that suggested complete comfort with P38 handling characteristics.

When Shimata’s damaged aircraft turned directly toward Lindberg in what appeared to be a ramming attack, the civilian pilot’s response was immediate and decisive. The brief engagement ended with Shimata’s aircraft spiraling toward the ocean, trailing smoke and debris. Lindberg had scored his first and only aerial victory of the war, but the significance extended beyond individual combat success.

He’d proven that fuelefficient cruise techniques didn’t compromise combat effectiveness when applied by pilots who understood both engine management and tactical flying. The return flight provided final confirmation of the techniques practical value. McDonald’s formation had been airborne for over 8 hours, including extended combat maneuvering at maximum power settings.

Standard fuel planning would have left most pilots calculating emergency landing options or considering water landings if headwinds increased. Instead, they landed at Helandia with fuel reserves that seemed almost luxurious. Macdonald touched down with enough fuel remaining for another hour of flight.

Maguire, who’d been experimenting with modified cruise settings throughout the mission, reported similar margins, but Lindberg’s fuel gauges showed quantities that still seemed impossible. Enough remaining fuel for nearly two additional hours of flight time. The ground crews post-flight inspections revealed no engine damage, no unusual wear patterns, and no mechanical problems that would suggest harmful effects from oversquare operation.

Kowalsski’s detailed examination of Lindberg’s engines actually showed slightly less wear than comparable aircraft operated under standard settings, suggesting that efficient cruise techniques might actually extend engine life rather than shorten it. Word of the combat success spread through the 475th Fighter Group with the speed of all significant military news. Lindberg had demonstrated fuel efficiency under the most demanding operational conditions, proven combat effectiveness against experienced enemy pilots and returned with engine condition that contradicted every warning about over square damage. Major Peterson approached Macdonald that evening with the grudging respect of

someone whose professional skepticism had been overcome by undeniable evidence. Colonel, I’d like to request permission to try Mr. Lindberg’s techniques on tomorrow’s patrol mission. The dam had finally broken. Within a week, every pilot in the squadron was experimenting with reduced RPM settings and autolean mixtures.

The results matched Lindberg’s predictions with mathematical consistency, 30% fuel savings, extended range capabilities, and no mechanical problems that hadn’t been predicted by obsolete training doctrine. Macdonald realized they’d witnessed more than a technical demonstration. They’d seen institutional knowledge challenged and overturned by evidence that couldn’t be dismissed or ignored.

By August 1944, the transformation was complete. What had begun as one civilian’s controversial suggestion had become standard operating procedure across every P38 unit in the Pacific theater. Flight manuals were hastily revised, technical orders rewritten, and instructor pilots found themselves teaching techniques that directly contradicted everything they’d learned during their own training.

The institutional revolution had occurred with startling speed, driven by results that commanders couldn’t ignore. Macdonald stood in the operations tent, studying mission planning boards that would have been impossible just months earlier. Routts stretched deep into Japanese- held territory, 950-m round trips to Balik Papan, extended patrols over the Calbe Sea, escort missions that pushed P38 capabilities to limits that previous doctrine had considered fantasy. The numbers told the story with mathematical precision.

Combat radius increased from 570 mi to 750 mi. Fuel consumption reduced by 30% and mission capability expanded by 40% in flight time. Colonel Lewis approached with the latest operational reports, his expression carrying the satisfied look of an officer whose tactical problems had been solved by unexpected innovation.

The 432nd squadron completed an 8-hour escort mission to Borneo yesterday. He reported full formation, no fuel emergencies, adequate reserves for combat maneuvering over target. The significance wasn’t lost on Macdonald. 8-hour missions had been theoretical discussions just 4 months earlier. Now they represented routine operations that pilots planned with confidence rather than desperate hope.

The psychological transformation matched the technical advancement. Crews no longer calculated fuel margins with the grim precision of men expecting to die from empty tanks over endless ocean. Technical Sergeant Kowalsski had become an unexpected expert on the new procedures, training ground crews throughout the Pacific on mixture settings and power management that maximized fuel efficiency.

His maintenance reports consistently showed engine condition that matched or exceeded standard operational parameters, definitively disproving decades of warnings about over square damage. Colonel Kowalsski reported during one of their regular maintenance briefings. Engines operated under Mr. Lindberg’s settings are actually showing less wear than comparable aircraft run at standard cruise power.

lower combustion temperatures, reduced mechanical stress, and improved fuel atomization are extending service life rather than shortening it. The technical vindication represented more than mechanical validation. It suggested that institutional knowledge codified in training manuals and perpetuated through military instruction could be fundamentally wrong about basic operational principles.

The implications reached far beyond fuel consumption into questions about how military organizations evaluated and adopted new information. Lieutenant Hayes, now one of the squadron’s most vocal advocates for the new techniques, had personally flown over 200 hours using Lindberg’s methods.

His log book documented fuel savings that accumulated into tactical advantages measurable in combat effectiveness. Sir, he told Macdonald during a mission debrief, “Yesterday’s patrol to Halmahara would have been impossible under old cruise settings. We flew for 9 hours, engaged enemy aircraft over target, and landed with fuel remaining for another hour of flight.

The human element had proven as adaptable as the technical systems. Pilots initially concerned about 9-hour endurance missions discovered that reduced engine noise and vibration from lower RPM settings actually decreased fatigue during extended flights. Cockpit comfort improved, oxygen system demands remained manageable, and the psychological pressure of fuel calculations diminished to acceptable levels.

Major Maguire had emerged as the techniques most effective advocate among combat pilots. His reputation carried weight throughout the fighter community, and his endorsement of Lindberg’s methods influenced pilots across multiple squadrons. “The old way of thinking about fuel management was killing us,” Maguire observed during a gathering of squadron leaders.

“Not through mechanical failure, but through self-imposed limitations that prevented us from reaching targets that should have been within our capability.” The strategic implications became apparent as mission planners realized that P38 units could now strike targets previously reserved for longer range bombers.

Japanese installations that had been beyond fighter reach were suddenly accessible to formations capable of flying nearly 10 hours with adequate fuel reserves for combat operations. The tactical balance in the Pacific shifted as American fighters gained operational range that matched the vast distances of oceanic warfare. Word of the fuel efficiency breakthrough spread through unofficial channels that connected P38 pilots across the entire Pacific theater.

Squadron commanders from Australia to the illutions began requesting detailed briefings on cruise techniques that promised to extend their operational capabilities. The informal network of communication that existed among fighter pilots carried technical information faster than official military channels.

Macdonald found himself fielding requests from units as far away as the China Burma India theater where P38 pilots faced similar range limitations over equally challenging terrain. The techniques that Lindberg had demonstrated over Pacific waters proved equally effective over Himalayan peaks and Burmese jungles, confirming that fuel efficiency principles transcended specific operational environments.

By late 1944, training squadrons in the United States had incorporated the new cruise procedures into standard instruction curricula. Newly graduated pilots arrived in Pacific combat units already familiar with techniques that their predecessors had learned through dangerous trial and error over hostile territory.

The institutional learning curve had been compressed from months of combat experience into weeks of systematic training. The statistical evidence became overwhelming as operational reports accumulated. Pilot survival rates improved measurably as fuel related emergencies decreased. Mission success rates increased as formations could remain over target areas for extended periods. Enemy installations previously protected by distance became vulnerable to regular attack by fighters capable of reaching them with adequate fuel reserves. Lindberg’s departure from Helandia in August 1944 marked the end of his direct

involvement with Pacific operations, but his technical contribution continued to influence combat effectiveness throughout the remaining war years. He left behind a cadre of pilots and ground crews who understood fuel management principles that would serve as foundation knowledge for jet-powered aircraft development in the post-war era.

The institutional lesson extended beyond aviation into broader questions about military doctrine and innovation. The P38 fuel efficiency breakthrough had demonstrated that conventional wisdom, even when supported by extensive training programs and technical documentation, could be fundamentally incorrect about basic operational principles. The speed with which new techniques replaced established procedures suggested that military organizations could adapt rapidly when presented with evidence that couldn’t be dismissed. McDonald’s final mission report to higher headquarters quantified the

transformation in terms that spoke directly to strategic planners. Combat radius extended by 31%. Fuel consumption reduced by 30%. Mission duration capability increased by 40%. These numbers translated into tactical advantages that influenced air campaign planning throughout the Pacific theater and established precedents for longrange fighter operations that would continue through the Korean War and beyond.

The quiet revolution that began with one civilian suggestion to try different engine settings had fundamentally changed how America’s most important fighter aircraft operated in the world’s largest theater of war. The lesson was both simple and profound. Sometimes the experts are wrong and sometimes saving fuel means winning battles.

News

THE MILLIONAIRE’S BABY CRIED WHEN HE SAW THE MAID — HIS FIRST WORDSs SHATTERED EVERYONE

The crystal glasses still vibrated when silence fell across the grand hall. Fifty high-society guests turned, confused, toward the same…

CH1 March 4, 1944: The Day German Pilots Saw P-51s Over Berlin — And Knew They’d Lost

March 4, 1944, Berlin, Germany. Luftwaffa fighter pilots scrambled from Templehof airfield to intercept incoming American bomber formations. Intelligence had…

CH1 The Dark Reason Germans Hated American M2 .50 Cal

While the Allies hated German machine guns in World War II for their incredibly high rate of fire, the Germans,…

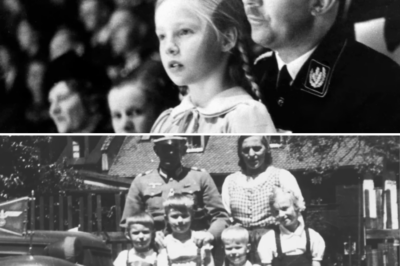

CH1 What Happened To The Children of Nazi Leaders after World War 2?

What secrets did the children of Nazi leaders hide when they grew up? How were their lives affected by…

CH1 What Happened To The Wives of Nazi Leaders After World War 2?

While the atrocities committed by high-ranking Nazi officials during World War II are widely known and documented, the lives…

CH1 What Happened to the German U-Boats After WW2?

When Nazi Germany surrendered in May 1945, more than a hundred U-boats were still at sea. In the days…

End of content

No more pages to load