The first time Anna saw him, the band was playing loud enough to drown the past.

The dance hall was a miracle of light in a ruined city. Outside, Berlin lay in heaps of stone and splintered beams, the smell of wet mortar and coal smoke caught in every street. Inside, someone had coaxed electricity from battered wires; bare bulbs swung from the ceiling and cast a hazy gold over faces that were too thin and too young and far too old.

Anna smoothed her hand down the front of her faded lace dress. It had been white once, worn to a cousin’s wedding in 1939 before ration cards and air raid sirens swallowed everything. Now it was yellowed and mended in three places, but it was what she had. Her factory shift had ended an hour ago; the hum of looms still buzzed faintly in her ears. Her fingers smelled of oil and cotton dust.

The air in the hall was thick with sweat, cheap perfume, and the sour tang of watered beer. Cigarette smoke wove itself between notes of music. A small band clustered on a makeshift stage — trumpets slightly out of tune, a saxophone that rasped at the edges, a piano missing a key. They were playing swing. American music. Music that had once been “degenerate” and forbidden, now permitted by command of the same men who marched through the city in olive drab.

She hovered near the door, back against the cool plaster, wondering if she should have come at all. Her brother’s letters from the front — the last ones, before they stopped — flickered in her mind. He had written of comrades blown apart, of mud and cold, of “them” advancing with endless artillery. He had never written of dancing.

Out on the floor, uniforms mixed with civilian clothes. British khaki, American olive, the blue of French forces, grey coats turned inside out to hide old insignia. German girls moved in tired dresses and borrowed shoes. Laughter rose in short bursts, too loud, a little desperate.

And there, near the edge of the crowd, she saw him.

He was taller than most, his dark skin gleaming in the lamplight. A black American soldier. She had seen a few in the streets, always at a distance, their presence a quiet challenge to everything she had grown up being told. This one moved with an easy rhythm, shoulders loose, feet tapping lightly to the beat. He wasn’t dancing yet, just… existing in the music, a smile flickering at the corners of his mouth.

Anna felt her hands start to twist the hem of her dress. Her stomach tightened. For years she had heard whispers about men like him — first from the radio, then from neighbors who murmured what “they” would do to German women. Even now, some in her district crossed the street rather than pass a group of black soldiers.

The band slid into a livelier tune. Horns blared a bright, brassy line that cut through the smoke. Someone bumped Anna’s shoulder, murmured an apology, then was swept away into the crowd of dancers. Her heart thudded. It would be easy to slip back out into the night, to walk home past darkened windows and piles of rubble, to go to bed with the ache in her legs and the whine of the machines still ringing in her bones.

But the music tugged at her feet, and something else tugged at her chest — a stubborn, quiet defiance. She had survived the last months of the war. She had stood in ration lines while the sky burned orange. She had watched her street collapse in dust and flame and crawled out of a cellar with mortar in her hair. Surely, she thought, she could survive one dance.

She took a breath and stepped forward.

As she moved toward the floor, the tall soldier turned. For a second their eyes met — hers a wary grey, his a warm, surprising brown. He smiled, the kind of smile that crinkled the skin at the corners of his eyes, and extended his hand as if it were the most natural thing in the world.

“Dance?” he asked, the word rounded by a southern accent she could barely understand, but the gesture spoke clearly enough.

She hesitated. The room seemed to still. Somewhere behind her, she imagined voices, disapproving clucks from unseen neighbors, warnings whispered in cellar corners. German girl with a black American. Shameful. Dangerous.

The trumpet soared, the drummer snapped his wrists, and Anna’s choice narrowed to two beats of her own heart. She put her hand in his.

His palm was rough, calloused, but warm and steady. He led her onto the floor, his other hand settling lightly at her waist. The band swung into the chorus, and he moved with the music as if it were another limb, guiding her through turns she didn’t know she remembered. Her shoes slid across boards worn smooth by bodies trying to forget.

“You’re a natural,” he said when the song ended, his breath a little quick. The German he’d practiced with comrades was clumsy but recognizable. “You dance good.”

Heat rose in her cheeks. “It has been… a long time,” she replied, her own English hesitant and thin from disuse. His smile widened at her effort.

They took a break at a small corner table, where a chipped glass of watery punch sweated onto scarred wood. The liquid tasted faintly of citrus and sugar, a luxury after years of ersatz drinks. Anna ran her thumb along a groove in the tabletop, grounding herself.

“My name is Anna,” she offered.

“Marcus,” he said, tapping his chest. “Marcus Hail.”

“From… where?” she asked, the question clumsy in her mouth.

“Louisiana.” The word rolled like a slow river. “Near New Orleans. You know jazz?” His eyes brightened. “Music like this, but… bigger. Wilder.”

She shook her head. “Only heard… on radio. Before.” Before the bans, before the bombs, before the war narrowed her world to sirens and factory whistles.

He nodded, as if he understood more of the unsaid than the words themselves conveyed. He spoke of home low porches and the smell of the bayou, of Sunday dinners and trumpets on street corners. She spoke of summers along the Spree, of picnics in parks that now existed only as cratered lots, of fireworks that had once been for celebration, not destruction.

Between them, language faltered, but rhythm did not. When the band started again, a slower number now, they rose almost without thinking. The dance this time was closer, the space between their bodies narrowed. Her cheek brushed the fabric of his uniform. He smelled of soap, starch, a hint of tobacco.

For the length of a song, the world shrank down to their shared center of gravity, to the brush of fabric and the sound of their breathing. The war receded, not erased, but held at bay by the simple act of two people moving together.

When dawn slipped pale and thin through the cracked windows, the hall emptied in tired clusters, boots scuffing the floor. Anna and Marcus lingered at their corner table, glasses empty, their minds reluctant to surrender the night’s fragile magic.

“Tell me your best memory,” he said, cigarette smoke curling from his fingers, words careful now, more deliberate.

She thought of answering lightly — a holiday, a dance, some harmless childhood scene. But the war had burned away much of what had been harmless. What remained was layered with loss.

“The river,” she said slowly. “Before. We used to swim at night. Lights on the bridges. It felt like the city was… singing.” Her voice caught. That river now carried debris and ghosts.

He nodded, eyes distant. “We had the bayou. Nights with fireflies so thick you’d think the stars came down to visit.” He smiled faintly. “I didn’t know other people lived like that. You know? Before I came here. Before I saw…” His sentence drifted off into places they weren’t ready to name.

They parted at the door, the air outside biting at her flushed cheeks. Curfew loomed. She walked home through streets that were still mostly shadow and rubble, her steps lighter than they had been in months. The memory of his hand at her back, the warmth of his laugh, and the way the music had filled the cracks inside her followed her like a second heartbeat.

After that night, life resumed its grey routine. Anna returned to the factory floor, to the clatter of looms and the grit that crept under her fingernails. Berlin continued to rebuild itself in fits and starts, scaffolds rising where walls had fallen. Bread lines wound through streets still littered with broken brick. News spread slowly, by radio and rumor.

But something in her had changed. She walked a little differently. Her coworkers noticed. “You’re humming,” one of them said over the machine noise, raising an eyebrow.

“Am I?” Anna answered, cheeks coloring, and bent over her work.

The first letter came in early autumn, thin envelope marked with foreign stamps and careful censor’s marks. Her name was written in English, the characters slightly wobbly but clear. She recognized his hand at once.

He wrote about patrols through a countryside that still bore the war’s scars — burnt-out farmhouses and fields pockmarked by craters. He spoke of nights in barracks when the men shared records, scratchy jazz spinning in corners of rooms that still smelled of boot polish and canvas. He remembered the dance hall, their clumsy words, her laugh like something he wanted to hear again.

Anna read the letter three times by candlelight, the flame guttering when the draft found cracks in the window frame. The paper smelled faintly of tobacco and something else she only identified as distance.

She answered the same night, tongue pressing against teeth as she formed the English words. She described the factory, the way thread burned under her fingers when it ran too fast. She wrote of markets that were still half empty but where sometimes, now, there were apples again. She wrote of her sister’s little boy, who cried whenever planes flew overhead, even when they were only American transports droning peacefully.

She did not write, not yet, about the way her chest tightened whenever she thought of him.

The letters continued. They traveled slower than their thoughts, sometimes taking weeks to cross the fading chaos of bureaucracy and borders, but they came. He sent a photograph once: himself leaning against a sandbag wall, uniform dusty, grin wide, a trumpet balanced in one hand. She traced his face with the pad of her finger until the gloss dulled.

In winter, he returned to Berlin on leave. They were careful, choosing quiet corners and back entrances. The dance hall had been patched up; the worst cracks plastered and painted. The floor had new boards. It looked almost respectable. The music had shifted with the mood of the times — fewer wild swings, more slow dances, melodies stretched like long, tired sighs.

They met for coffee in a café that smelled faintly of real beans, rare and precious, and of the coal smoke that clung to everyone’s clothes. Snow lay in grey ridges along the gutters outside.

“You made it through the storm,” he said when she arrived, standing to pull out her chair, flakes still melting on his shoulders.

“You too,” she answered, unwinding her scarf. Her fingers tingled as warmth seeped back into them.

They spoke of small things and large. His unit, still stationed in the city, now more peacekeeper than conqueror. Her mother, who refused to leave the ruins of their old neighborhood even when offered a room in a newer block. The way Berliners had started to smile again, tentatively, as if testing an old muscle.

Later, they stepped back out into falling snow. The city was muffled. Footsteps sounded soft, almost secret. They looped arms to share warmth, their breath visible in the cold.

He reached into his pocket and produced a small bundle. The wool gloves inside were neatly knitted, navy blue, soft against her palms.

“For your walks,” he said. “Can’t have you freezing those hands.”

Her throat tightened. “You… you made these?”

“Lord, no,” he laughed. “My sister did. I told her about you. She said, ‘That girl needs decent gloves.’”

The thought of him speaking of her, across an ocean, to family she would probably never meet, felt like another kind of warmth entirely.

As the seasons turned, their connection grew roots. They met when his duties allowed — by the river as the trees budded green, in shady parks when summer pressed down heavy, over mugs of thin coffee when autumn painted the city in rust and gold. Each meeting carried the same blend of joy and the ache of everyone else’s eyes.

Not everyone approved. Some neighbors stared when they heard American boots on their stairwell. A few coworkers stopped talking when they saw her laughing with him outside the factory gate. The war had ended, but borders inside minds remained.

One evening in spring, as they walked along the Spree with the water licking softly at the stone, Anna spoke the fear aloud.

“They will talk,” she said. “My aunt already does. She says I dishonor my brother by…” She faltered, searching for words. “…by holding hands with the enemy.”

Marcus looked out over the river. The light caught lines at the corners of his mouth that hadn’t been there a year ago.

“I know about people talking,” he said quietly. “Back home, folks have plenty to say about a man like me dancing with a white girl. Different war, same whispers.” He squeezed her hand. “We can’t live by their voices. We live by ours.”

It wasn’t easy. The moral math of postwar Berlin was messy. Who had supported what and when couldn’t always be untangled. But the simple fact of his presence beside her, the way his thumb rubbed circles into her palm when she grew anxious, made it easier to breathe.

They made small plans, because big ones seemed too dangerous, too greedy. A trip to the countryside in summer, renting a little room at the edge of a village untouched by bombing. They did it, catching an early train that rattled through fields lush and wild, stepping into air that smelled of hay and clean water instead of smoke.

The cottage they found had crooked floors and a kettle that sang on the stove. They walked barefoot in a stream, the stones cold under their feet. He hummed a tune she didn’t know, and she joined in off-key, laughing when he spun her on the grass.

At night they sat on a wooden porch, the sky dark and wide in a way the city no longer allowed. Crickets chirped. Stars pricked the sky. Her head bent against his shoulder, the rise and fall of his breath a steady anchor.

“You’ll have to go back,” she said once, the truth one of those hard stones that can’t be stepped around forever.

“Yeah,” he answered. “We all will. They say soon. Rotation. But soon ain’t today.” He kissed the top of her head. “We’ve got this. For now, that’s enough.”

It was, and it wasn’t.

When the order came — redeployment, stateside rotation — it arrived in the form of a folded paper and tightened shoulders. His leave shrank. Patrols increased. The dance hall suddenly felt more precious and more fragile than ever.

Their last night there, the band played as if trying to hold back time. The hall had been repainted. The scars on the walls scrubbed or plastered over, but the scratches remained in the floor, reminders of heavier boots.

They danced every song, fast and slow. Her feet burned in her shoes. Sweat dampened the back of his shirt where her hand rested. When they finally sat, breathless, she stared at his hands on the table — strong, capable hands that had held a rifle, held her, written letters across an ocean.

“I don’t know how to say goodbye,” she admitted, voice raw.

“Then don’t,” he said. “Say ‘see you later.’”

“Will I?” she asked.

He didn’t lie. “I don’t know. But I know this: you’re part of my life now. Whatever happens, that stays.”

They walked out into cold night air, the streetlamps casting pale circles that pooled on the pavement. At her door, they stood too long, words thinning out.

“Thank you,” she said finally, and it sounded inadequate for all that had passed between them.

“For what?” he asked softly.

“For making me remember I’m alive,” she answered. “Not just… surviving. Alive.”

He gathered her into one last hug, the kind you give when you don’t know if there will be another. Then he stepped back, saluted her with two fingers and that crooked, tired grin, and walked away down the street until the shadows swallowed him.

Letters continued for a while. They took longer now, the routes more tangled as units redeployed. He wrote from a port, from a ship, from a base in the States. Then, one winter, they stopped. The last letter spoke of studying on the GI Bill, of maybe joining a band, of trying to find a place in a country that still sorted people like him into separate train cars and back doors.

Her letters kept going for months after the silence, until she finally put down her pen and accepted that life sometimes pulls threads out of our hands no matter how tightly we hold.

Years passed. Berlin rebuilt itself again and again. Walls went up and came down. Anna kept working, eventually leaving the factory for a job in an office that printed programs for theaters. Music returned to the halls. She married once, briefly, to a man who couldn’t understand why she always paused when an American jazz record played. They parted kindly.

She didn’t talk about Marcus often. When she did — to a niece writing a school paper, to a historian with a tape recorder — she always returned to the same night.

“The first time he reached out his hand,” she would say, “I thought everything I had been told would happen. And then nothing did. Nothing awful. Just… a dance.”

She kept a box in the back of a wardrobe with his letters, yellowed now, and the photograph he’d sent from the barracks. Once, after a particularly bad winter when she’d caught a fever and the doctor had mentioned mortality with professional frankness, she took them out and reread every line by lamplight.

In the margin of one, she noticed a note she had forgotten she’d made, in her own hand, decades earlier: “When he lowered his hand, all the posters in my head burned.”

Historians like to say that nations are changed by treaties and elections. That is true. But sometimes they are also changed by small things that don’t make it into official records: a chocolate bar offered instead of a shot, a clean bandage, a pair of wool gloves, a dance in a battered hall.

In 1945 Berlin, a young woman and a young man crossed lines that should have kept them enemies. They did it with music, with words broken and mended, with steps taken one at a time across a scarred floor. The war did not end because of them. No borders moved. No governments fell.

But in a world rebuilt from ruins, people like Anna carried forward a quieter victory: the memory that even when told to fear and hate, they had seen another way.

And somewhere in Louisiana, perhaps, or Chicago, or New Orleans, a man named Marcus might have stood on his porch years later, hearing a distant jazz tune on the radio and thinking of a night when the horns blared in a cold city and a German girl in a faded lace dress took his hand.

News

(CH1) Admirals Called Her Chalk Trick “STUPID” – Then It Saved 48,000 Lives

At 6:43 on a raw March morning in 1943, a nineteen-year-old woman stood in a cold Liverpool basement and looked…

(CH1) How One Girl’s “SILLY” Chalk Trick Made German U-Boats Sink 3 Times Faster

At 6:43 on a cold Liverpool morning in March 1943, a nineteen-year-old woman stood in the middle of a painted…

(CH1) How One 14-Year-Old Girl’s “Crazy” Bicycle Trick Killed Nazi Officers

In the history of warfare, death usually wears a uniform. It arrives with the thunder of artillery, the scream of…

(CH1) How One US Woman’s “Shopping Trips” Saved 7,000 Allied Pilots from Nazi Prisons

March 2nd, 1943. Marseille. The coded telegram was short, cold, and devastating. “Pat has fallen.” Four hundred kilometers away, in…

(CH1) How One American Woman’s Torn Typewriter Ribbon Saved 3,000 Lives and Sank 4 Japanese Carriers in 5 Hours

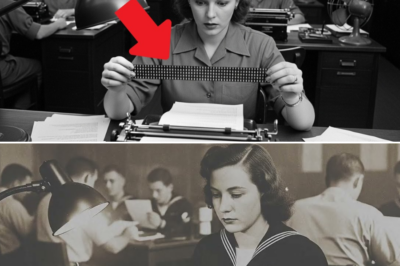

At 4:17 a.m. on May 25th, 1942, the ocean was still dark outside Honolulu, but inside the Fleet Radio Unit…

(CH1) How One Female Sniper’s “CRAZY” Trick Took Down 309 Germans in Just 11 Months

5:47 a.m. – August 8th, 1941. Belaya Tserkov, Ukraine. Twenty-four-year-old history student Lyudmila Pavlichenko crouched behind a pile of shattered…

End of content

No more pages to load