On March 18th, 1945, when the transport train finally shrieked to a halt outside Camp Gordon, Georgia, Greta Hoffmann pressed her face against the rough wooden slats and tried to see what waited for them.

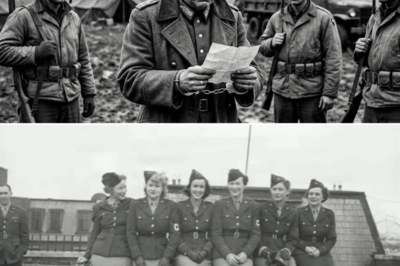

For six months she had been moving—east, then west, then south—retreating across a frozen continent as front lines dissolved and were drawn again. The Wehrmacht auxiliary uniform she had once worn with stiff, careful pride now hung on her like a burial shroud, gray-green stained to the same dead brown as the caked mud at its hem. She could smell herself. She could smell all of them: sweat and old fear and unwashed flesh, the sour note of clothes worn too long, the heavy, inescapable stench of defeat.

The doors slammed open and American voices barked orders in harsh, accented German.

“Raus! Los! Move!”

Greta’s breath caught. This was the moment the instructors in Berlin had warned about in low, dangerous tones. The newsreels had shown American soldiers as slack-jawed brutes, laughing as they tortured prisoners and dragged women into barracks. Her sister Elsa had written from Hamburg about the firestorms—about children burned alive in cellars while bombs walked across the rooftops. “These are the people doing this to us,” Elsa had written. “They are not human.”

Nine hundred thirty-two women stumbled out into the Georgia sunlight. Greta blinked rapidly. The light was different here, bright and flat, not the thin gray of a German winter. The camp ahead of them looked, at a glance, like the camps she knew: rows of wooden barracks, high fences, watchtowers at the corners.

But something was wrong.

The Americans weren’t sneering.

They weren’t jabbing them with rifle barrels or striking anyone who moved too slowly. They were… looking. A young GI, he could not have been more than twenty, turned to his sergeant with his face drawn tight.

“Jesus Christ, Sarge,” he muttered. “Look at them.”

The sergeant’s jaw clenched. “Get the doc,” he said. His voice was flat, but there was something under it that sounded more like anger than contempt.

Greta understood every word. Six years of English lessons in Bremen before the war had not deserted her. The auxiliary corps had told her to hide that knowledge. Never show the enemy what you know. Never show weakness. She kept her face blank and her eyes unfocused, but inside her mind raced.

The camp doctor arrived at a quick trot. He was smaller than she expected, with wire-rimmed glasses and thin shoulders under his officer’s jacket. He walked slowly along the line of women, studying each face without touching anyone. She watched his expression change from clinical appraisal to something sharper.

“How long since they’ve bathed?” he asked the American officer in charge of the transport.

“Intelligence says they’ve been retreating on foot five, maybe six months,” the officer replied, scanning his own papers. “Poland. Czechoslovakia. Doubt they’ve seen proper facilities since.”

“Six months,” the doctor repeated.

The number hung there, absurd and damning.

He took off his glasses and cleaned them with hands that shook.

“Get them to the quarantine barracks,” he ordered. “Set up the bathhouse. Full medical inspection tomorrow. And someone find clean clothes. Anything. I don’t care if you have to requisition civilian supplies.”

Greta listened and thought: a bathhouse. Hot water. It has to be a trick. What would she have written, back in the propaganda office? “The Americans lure prisoners with promises of comfort, then crush them.” It would have sounded right. It would have sounded plausible.

The women were marched to a long, low building at the edge of the compound. On the outside it was unremarkable: wooden walls, small windows, a tin roof. Inside, it was something else entirely. Real bunks. Springs that creaked but did not collapse. White sheets, thin but clean.

Greta sat on the edge of one and pressed her palm into the mattress. It held. She could not remember the last time her weight had been supported by anything but straw on stone or bare earth. Beside her, a girl named Maria—a former telegraph clerk from Kiel—began to cry. The tears cut clean trails through the dirt on her cheeks.

“Don’t,” Greta whispered. “Don’t give them anything.” She meant: don’t let them see what this does to you. Don’t let them know how far you’ve fallen.

But Maria wasn’t crying from fear.

Her fingers traced the curve of the metal bedframe and the border of the white sheet.

“It’s real,” she whispered back. “It’s actually real.”

An hour later, a woman in U.S. uniform appeared at the door. The chevrons on her sleeve marked her as a sergeant. A clipboard dangled from one hand.

“Badezeit in dreißig Minuten,” she said in careful German. “Bathing rotation in thirty minutes. Groups of twenty. You will have hot water, soap, towels. Clean clothes after medical exam tomorrow.”

Silence met her statement. Nine hundred thirty-two pairs of eyes stared with identical suspicion. The sergeant shifted her weight.

“I know you don’t believe me,” she added. “But this isn’t a trick. You are prisoners of war under the Geneva Convention. That means you will be treated as human beings.”

She turned to go, then glanced back.

“Essen um achtzehn Uhr,” she said. “Dinner at eighteen hundred. Mess hall is on the east side.”

Dinner. The word felt obscene. In the last camp in France, they had received a tin of thin turnip soup and a piece of bread a day if they were lucky. Here, the enemy spoke of “dinner” like it was a normal part of the day.

The bathhouse stood at the north end of the camp, a long wooden structure with steam already rising from vents near its roofline. Greta went in with the third group. Twenty women shuffled through the doorway, shoulders brushing. Inside, rows of chest-high wooden tubs lined the walls, each filled with water that smoked and shimmered in the air.

Greta could smell it from the door. Heat. Soap.

Real soap sat on little wooden benches next to each tub: white bars smelling faintly of something she could only call “before”—before the war, before the shortages, before the smell of fear replaced the smell of home.

An American nurse stood by the entrance, sleeves rolled, hair tucked neatly into a cap.

“Twenty minutes,” she said, and the interpreter repeated it. “Wash thoroughly. Razors are there, if you want them. Clean uniforms will be on the shelves.”

Then she stepped aside.

Greta approached her tub as if it might disappear. Her hands shook when she put her fingers into the surface of the water.

Hot.

Actually hot.

She looked around for the cameras, for guards with rifles leveled, for some sign that humiliation would follow. The Americans had already left the building. Someone was by the door—not inside, but outside, smoke from his cigarette curling past the small windows.

They had left them alone.

She undressed slowly. The uniform, stiff with dirt and sweat, fell to the floor in a heap. For a second she saw herself as if from outside: skin covered in a gray film, hair matted, ribs pushing against thin flesh. Then she stepped into the tub.

The water closed around her calves, her thighs, her waist, her ribs.

Heat hit her like a blow.

She sank down until it reached her shoulders and closed her eyes. It was too much. It was everything she had wanted and had not let herself hope for because hope had become dangerous. Something inside her felt tight and hard, like ice. In that moment, it cracked.

She grabbed the bar of soap and scrubbed. Brown swirls spun away from her arms. Dirt left in the wrinkles of her knuckles vanished. She washed her scalp, feeling lice under her fingers for the last time, then feeling only skin.

Around her, other women did the same. No one talked. The splashing and soft breathing and the occasional choked sob were the only sounds.

Twenty minutes later, wrapped in a towel, Greta stood before a mirror she barely recognized as such; she had not seen her reflection full-on in months. The woman who looked back at her had hollow cheeks and dark circles under her eyes, but her skin was pink. Clean. Her hair was cropped short now, shorn back in a delousing line at a transit camp, but without the thick crust of grease and dirt it looked less like a statement of shame and more like a severe, practical style.

The radio operator at her side—Helga, from Dresden—touched her own cheek in the mirror as if testing whether the face would dissolve.

“Why?” Helga whispered. “Why are they doing this?”

Greta had no answer.

That night, the mess hall filled with the sound of nine hundred women trying not to look desperate as they accepted metal trays from American cooks. The smell hit them first: scrambled eggs, bacon, toast browned and glistening with butter, coffee that smelled like the 1930s. Potatoes. Fruit in syrup.

Greta stared down at her plate, throat tight. The man behind the counter was already moving to the next tray.

“Keep moving, ma’am,” he said. “Line’s backing up.”

Ma’am.

She found a seat at a heavy table and sat opposite Maria, who held a slice of bacon between her fingers as if it might evaporate.

“My brother wrote from Hamburg,” Maria said in a voice that shook. “They are eating bread made with sawdust. Potato peels. Sometimes nothing at all.”

She took a bite. Her eyes closed.

“We are eating better here than they are,” she whispered. “Better than our families.”

The realization fell on the table like a lead weight. It made the food on Greta’s plate feel heavier. She ate mechanically, the stew soft and rich on her tongue, her mind skipping thousands of kilometers away to a flat in Bremen where her mother might be boiling gray water and pretending it was soup.

When mail finally came, forwarded from Europe through the Red Cross, the distance between those worlds became unbearable.

The envelope with her mother’s handwriting arrived on April 15th. Her fingers fumbled as she opened it.

Her mother wrote of ration cuts and an apartment building next door destroyed in a single raid, “all gone in the flames.” Of her father’s factory taken over by the SS. Of her younger sister, Katharina, listed as missing after some convoy was hit outside Dresden.

“Missing.” Not dead. Not safe. Suspended somewhere between.

“We are grateful you are alive,” her mother wrote. “Please, stay that way. Come home when this is over.”

Greta read the letter three times. Then she went to dinner and filled her tray with beef stew, bread, and real butter.

She sat with the others as they read their own letters. Their words were all different and all the same: Hamburg burning; Berlin surrounded; fathers shot for saying the wrong thing; brothers dead in Russia or the Ardennes; mothers boiling wallpaper paste for food.

Here in Georgia, someone passed the salt.

“How are we supposed to live with this?” Maria asked, staring at her plate. “They starve while we eat. We wear enemy uniforms, and they call us ‘ ma’am’.”

The only answer Greta could think of was troubling: the Americans were keeping their promises. The Reich had not.

The transformation, for many of them, was not a single thunderclap but a series of soft impacts—impressions that accumulated until the old structure of belief could no longer bear the weight.

At first it was just the baths and the food.

Then it was the doctors.

Medical examinations at Camp Gordon were conducted with privacy and professionalism. Curtains were drawn. Female nurses did what they could. American doctors treated ear infections, set broken fingers that had been splinted badly months ago, prescribed iron supplements for anemia. The camp dentist, a cheerful man from Ohio, apologized before every injection and joked in a way that did not feel cruel.

In the barracks, sheets were changed weekly. Blankets were thick and plentiful. The women were made to work, but not to exhaustion: laundry, kitchen, clerical tasks. For this, they received camp script that could be exchanged at the canteen for toothbrushes, hair ribbons, chocolate, and cigarettes. Luxuries beyond imagining in bombed-out Bremen or Berlin.

Then there were the faces.

Greta began to notice that the guards and staff did not all look alike. In the laundry she saw a black sergeant and two white privates joking together, their body language easy, the sergeant’s authority unquestioned. In roll call she heard a woman’s voice, sharp and precise, as a female lieutenant checked names, and watched male guards obey her.

On a door near the administration building, a nameplate read: “Camp Commandant – Col. David Rosenberg.”

When she heard, quietly, that he was Jewish, something inside her twisted. A Jewish colonel commanded a camp full of German prisoners and used that power to ensure they were housed, fed, and treated according to laws his own people had been denied.

The contradictions piled up.

In the library, she found shelves of German books the Reich had banned. Thomas Mann. Stefan Zweig. Freud. Authors labeled “degenerate,” “Jewish,” or “un-German” by the ministry that had employed her. She read Mann’s essays on what Germany might have been—a Germany of poets and philosophers instead of uniforms and parades—written from a safe house in California.

She cried over some of those pages, not only for what Germany had done, but for what it had failed to be.

On May 8th, the camp loudspeaker crackled to life.

Germany, the voice said first in English, then in German, had surrendered unconditionally.

The war in Europe was over.

Greta stood in the yard with hundreds of other women and felt… nothing. No surge of pride, no wave of grief, just a hollow fatigue. The Reich that had promised a thousand years had lasted barely twelve. It had brought her to a fenced compound in Georgia and left her family under rubble.

That night, instead of a comedy, the Americans showed a film.

The projector clattered, the lights dimmed, and onto the hung sheet came images that did not allow for illusions. Barbed wire. Emaciated men and women in striped uniforms. Stacks of bodies. Pits being filled by bulldozers. Signs: Dachau. Buchenwald. Bergen-Belsen.

On the screen, American and British soldiers forced German civilians from nearby towns to walk through the camps and look. Women in neat coats and hats pressed handkerchiefs to their mouths. Men in fedoras and work jackets stared at corpses and the ration charts that explained how many calories each prisoner had been allotted.

“We didn’t know,” someone whispered in the dark.

But some of them had known enough. Greta thought of Jewish neighbors who had vanished in 1941, of the vague but persistent rumors about “the East,” the euphemisms they had learned to live with—Special treatment. Final solution. She had never seen it. She had not wanted to.

Colonel Rosenberg stood at the front when the projector stopped.

“You are wondering,” he said through the interpreter, “why we show you this. Why we treat you in accordance with the Geneva Convention and then make you watch these horrors.

“It is because you must understand two truths at once: what was done in your name—and how we choose to respond to what has been done in ours.”

He looked at them, not with hatred but with a weary, unsparing gaze.

“You served a system that broke its own laws and ours. We will not break ours in return. That is not leniency. That is who we are.”

The double blow landed hardest of all. The enemy had both the power to crush, and the restraint to not use it. The Reich had done the opposite.

Repatriation came slowly. It took months for the flood of prisoners to be processed, transported, and dispersed back into a shattered Europe. Greta worked in the meantime in the camp’s administrative office, filing forms in English and German, translating where needed. She took English classes in the evenings, taught by a lieutenant from Vermont who believed, as he told them, that “if you’re going home to help rebuild, languages will be tools, not decorations.”

“Why are we learning this?” one woman asked. “To serve you?”

“To serve yourselves,” he replied. “To serve Germany, if you want to make it something better. Or simply because knowing more is better than knowing less. That’s your choice.”

Choice.

In a system where the default answer to “why?” had been “Because the Führer says so,” the idea that choice might exist even in captivity felt strangely subversive.

In August, Greta sat through a denazification interview in Bremen. The German official working with the Americans asked dry questions about party membership and activities. She answered truthfully. No Party card. No stormtrooper rallies. Work in the auxiliary corps. Time as a prisoner in America.

“You say they treated you well?” he asked.

“Yes,” she said.

“Why do you think that is?”

She thought of bathhouses and mess halls. She thought of black sergeants and Jewish colonels. She thought of shaved heads used to kill lice versus shaved heads used to strip humanity.

“Because they believe the words printed in their own laws,” she said slowly. “Human rights. Dignity. Rule of law. We studied those words too, in school. Kant. Schiller. But when they became inconvenient, we threw them away. They did not.”

“And what do you do with that understanding?” the official asked.

“I live with it,” she said. “I use it to decide what kind of German I will be now.”

He stamped her papers. “Cleared for employment,” he said.

The ruins of Bremen began, painfully, to knit themselves back together. Streets were cleared. Bridges patched. Schools reopened in undamaged rooms. The Marshall Plan funds would come later, but even in 1946, Allied administrators pushed for some semblance of normal life: bakeries baking again, clinics seeing patients, newspapers printing more than ration notices.

Greta took work as a translator in the Allied administration building. Every day she bridged English and German, moving words back and forth. Policies. Complaints. Requests. Regulations.

Trucks came and went in the streets outside—American vehicles bringing in food supplies, British lorries hauling coal, German carts carrying bricks. On her walk home, she passed people queuing with empty pails, women scrubbing soot from surviving doorways, children playing among broken walls.

Letters arrived from Maria in Hamburg, from Helga in Dresden, from others who had shared that first bewildering bath in Camp Gordon. They all said versions of the same thing: the country is wrecked; the people are hungry; and we cannot forget what we saw in America.

“Do you remember that first night?” Maria wrote. “When we thought the officer was lying about the hot water? When we thought kindness was a trick? It wasn’t. That, more than anything, is what I bring home: proof that mercy is possible. That we don’t have to be what we became.”

When Greta’s grandchildren came to her, years later, with schoolbooks filled with photos and timelines, they would ask her what the war had taught her.

She did not lead with battles or marches or the slogans she had once repeated.

She told them about a long line of women who smelled of six months’ retreat stepping off a train into Georgia sunlight, braced for blows.

She told them about a camp doctor whose anger was directed not at them, but at what had been done to them.

She told them about the first time in half a year that hot water hit her skin, and about an enemy nurse who nicked her scalp and apologized.

She told them about eating bacon and eggs in a mess hall in a foreign country while letters from home described sawdust bread and burning furniture.

She told them about the knowledge that followed:

“The Americans had every reason to hate us,” she would say. “We had bombed their cities. Our submarines had sunk their ships. Our leaders had built the camps you see in your history books. But the first thing they did was give us soap. They were teaching us something. Not with speeches, but with how they treated us.”

If they asked her what that something was, she would answer carefully.

“That dignity doesn’t belong to one nation or one race,” she said. “That laws are only as good as those who choose to obey them when it would be easier not to. That mercy, when it crosses enemy lines, can collapse a lifetime of lies in a single moment.”

The bathhouse in Georgia, the mess hall, the library with banned authors—these were small pieces of a vast, brutal war. They didn’t negate the firebombings, the misery of occupation, the massacres on the Eastern Front. They didn’t absolve her, or anyone else, of what they had believed or ignored.

But they gave her—and hundreds of women like her—a permanent, uncomfortable comparison to carry: between a regime that had spoken eloquently of culture and human worth while building death camps, and an enemy that had shown, again and again, that even in victory there were lines it would not cross.

The war had ended in ruins and loss. Out of that, Greta salvaged this one clear memory: an American soldier, a stranger whose language she barely spoke, stepping back from a tub of hot water, nodding toward the soap, and giving her, without saying a word, permission to be human again.

The rest of her life, she tried to live as if that fragile permission mattered.

News

(CH1) FORGOTTEN LEGEND: The Untold Truth About Chesty Puller — America’s Most Decorated Marine, Silenced by History Books and Erased From the Spotlight He Earned in Blood 🇺🇸🔥 He earned five Navy Crosses, led men through fire, and left enemies whispering his name — yet most Americans barely know who Chesty Puller really was. Why has the full story of this battlefield titan — his brutal tactics, unmatched loyalty, and unapologetic grit — been buried beneath polite military history? What really happened behind closed doors during the fiercest battles of WWII and Korea? And why has one of the Marine Corps’ most legendary figures been all but erased from modern memory? 👇 Full battle record, unfiltered quotes, and the shocking reason historians say his legacy was “intentionally softened” — in the comments.

Throughout the history of the United States Marine Corps, certain names rise repeatedly from battlefields and barracks lore. Many belong…

(CH1) A 19 Year Old German POW Returned 60 Years Later to Thank His American Guard

In the last days of the war, when Germany was nothing but smoke and road dust, a nineteen-year-old named Lukas…

Woman POW Japanese Expected Death — But the Americans Gave Her Shelter

By January 1945, Luzon was on fire. American artillery thudded across the hills. Night skies flickered with tracer fire. Villages…

Japanese ”Comfort Girl” POWs Braced for Execution — Americans Brought Them Hamburgers Instead

By the last year of the Pacific War, the world those women knew had shrunk to jungle, hunger, and orders…

(CH1) Female Japanese POWs Called American Prison Camps a “Paradise On Earth”

By the winter of 1944, the war had shrunk the world down to barbed wire and fear. Somewhere in the…

(Ch1) Former Goebbels Officer Expects Torture in US Prison Camp—What He Gets Instead Breaks Him Completely

When the headline caught his eye, Eric Müller thought at first he had misread it. “President criticized for policy failures.”…

End of content

No more pages to load