Story title: Saying Yes

Central Germany

May 1945

For the first time in years, the guns were quiet.

The silence pressed in on the little town like a physical thing, filling the cracks that bombs had carved into the streets and settling over the hospital that still stood, miraculously, at the edge of the ruins.

Inside, the sounds were smaller now.

Bandage wrappers crinkling. Low moans. The squeak of a stretcher wheel that desperately needed oil.

Greta stood in the narrow corridor outside Ward C, fingers curled around a tray dotted with bottles and dressings, and listened to the quiet the way she used to listen for incoming artillery. Suspiciously. Carefully. As if it might explode.

Two weeks ago, the war in Europe had ended.

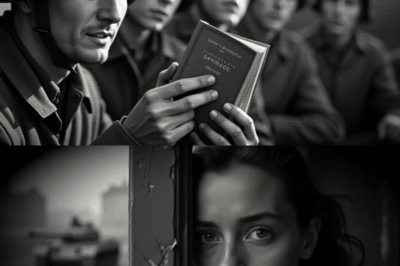

The paper with the announcement had been passed from hand to hand, eyes racing over words that didn’t feel real: capitulation… unconditional surrender… peace.

The buildings outside still looked like missing teeth in a broken jaw. The people still looked like ghosts.

But slowly, impossibly, the hospital had started to smell less like smoke and blood and more like carbolic and coffee.

The Americans had come quickly on the heels of the capitulation—jeeps rolling through the shattered streets, uniforms clean, faces young and tired and strangely open.

They’d set up a command post in the town hall and sent a medical detachment to the hospital.

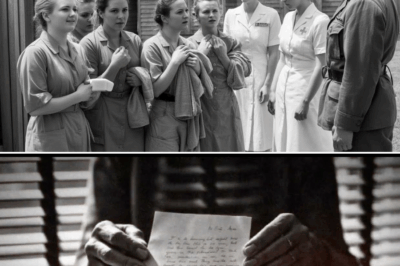

The nurses—German women who’d been working through the war since 1939—had braced for orders, for interrogation, for replacement.

Instead, the Americans had walked into their wards and rolled up their sleeves.

Greta had watched it all with the same numb detachment she’d cultivated on the Eastern Front. Shootings, amputations, slow deaths by infection—she’d seen enough that nothing surprised her anymore.

Or so she thought.

Then a farm boy from Iowa smiled at her like she was a person and not just another set of hands, and she discovered she wasn’t as numb as she’d believed.

James Carter was twenty-one and felt a hundred.

He’d never seen a building collapsed by artillery before he came to Europe. Never seen a body torn apart by a mine. Never heard a grown man whimper for his mother in a language he didn’t understand.

Now he’d seen all of that and more.

But he’d also watched an old German woman take a biscuit he offered and press it to her cheek like it was a baby. He’d heard a kid laugh at a joke he’d mangled in broken German. And he’d watched the nurse with the dark hair move through the ward with a kind of tired grace that made his chest ache.

Her name was Greta.

He’d learned that the first day, when the American medics had been introduced to the German staff.

“Greta Müller,” she’d said, voice soft but steady. “Schwester—nurse.”

“James Carter,” he’d replied. “Medic.”

Their hands had met briefly—hers cool, callused at the fingers; his warm, rough from cornfields and now from hauling stretchers.

That afternoon, they’d moved a patient together.

The man on the cot was barely twenty—German infantry, shrapnel wounds in his thigh. He’d gritted his teeth and tried not to cry out as they shifted him.

“Eins… zwei… drei,” Greta had counted, and they’d lifted in unison.

For a split second, their fingers brushed where they met under the frame.

It was nothing. Everything.

James had said, “Sorry,” automatically.

Greta had shaken her head.

“Is okay,” she’d said in English, the words accented but clear.

After that, he’d found excuses to be in whatever ward she was in.

He told himself it was efficient.

They worked well together. She knew the layout. He had supplies. Between the two of them, they could triage a room twice as fast.

It was efficient.

It was also the first time since he’d landed in Europe that he’d felt something like… forward.

The war had pushed him in one direction for a year.

Greta made him feel like there might be another one.

The town they lived in was called, officially, something like Forthausen. The Americans just called it Fort.

The hospital had once been a respectable two-story brick building with a tiled roof. Now part of one corner was missing, and half the windows were boarded up. But the walls still stood. The wards still held beds. The staff still did what they always had: fought to keep people alive.

The nurses ranged from girls barely out of school to women old enough to have sons at the front. They’d started the war believing in slogans—Führer, Volk, Vaterland—and ended it believing in bandage rolls and the way a pulse felt under their fingers.

Germany’s men were gone.

Dead.

In camps.

On the road, trying to walk home from a collapse that had stretched across a continent.

Greta’s were.

Her father, a railway clerk, had been killed in ’43 when an Allied bomb hit the station. Her mother had died in a firestorm the next year, lungs full of smoke that no one could get out.

Her younger brother had disappeared in Russia.

The house she’d grown up in was now a pile of bricks and memory.

The hospital was all she had left.

Well—almost all.

Now there were these Americans. With their endless cigarettes, their strange slang, their letters from places like Iowa and Ohio and Massachusetts. With their way of looking at her that wasn’t pity, wasn’t appraisal, wasn’t just exhaustion.

One afternoon, as she was changing the dressing on an older patient’s chest wound, she felt eyes on her back.

She turned.

James stood in the doorway, a basin in his hands.

He smiled.

Not the shy, quick smile he sometimes gave when he’d mispronounced a German word.

A real one.

Greta’s heart did a strange little skip.

She was careful not to show it.

She’d spent six years being careful. Careful what she said about the regime. Careful who she trusted. Careful not to hope.

Hope got you shot.

Or hurt.

Or simply disappointed one more time.

But that night, sitting on the front steps of the hospital with the sky bleeding from gray into dark, she realized that something in her had shifted.

For the first time in years, she’d noticed a man’s smile and thought of something other than morphine doses and evacuation orders.

The evening James sat next to her with two cups of coffee, the sky was clear.

Clear skies had meant bombers, once. Now they meant you could see the stars.

He’d scrounged the coffee from the American mess tent, pouring it into two chipped mugs like it was contraband.

He set one beside her without a word.

She looked at it.

Steam curled up, carrying the sharp, bitter scent. It had been months since she’d smelled coffee that wasn’t made from roasted barley.

“Danke,” she said.

“You’re welcome,” he said.

They sat in silence for a long while.

The hospital behind them hummed quietly—murmurs, the creak of beds, someone snoring.

Ahead of them, the town lay in shadow, jagged outlines of half-collapsed roofs against the darkening sky.

“Do you have… Familie?” he asked finally, reaching for his dictionary.

He flipped it open to the page where he’d underlined family.

She stared at the word for a moment.

“Hat-sich”—he winced—“do you have family? Mutter, Vater, Geschwister?”

She wrapped both hands around the mug.

“No,” she said.

Her voice came out flat.

“My parents are… tot,” she added, searching for the English. “Dead. In… Bombenangriff. Bombing. My brother… Ostfront. Russia. Keine… no Nachricht. No news.”

He swallowed.

“Es tut mir leid,” he said. “I’m… sorry.”

She shrugged one shoulder.

“So ist es,” she said. That’s how it is.

She turned the question back on him.

“And you?” she asked. “Family?”

“Ja,” he said. “Yes. Mutter, father, Schwester. Little sister. In Iowa.”

He said the last word like it meant something.

“What is… Iowa?” she asked.

His mouth curled.

“Flat,” he said. He spread his hand parallel to the ground. “Very flat. Corn.” He mimed stalks growing tall. “Cows. Pigs. Groß Feld. Big fields. One small town. Church, school, two shops.”

“Sounds… langweilig,” she said, trying out the English word. “Boring.”

He laughed.

“Yeah,” he admitted. “It was. I wanted to leave. See the world. Careful what you wish for.”

She smiled, small.

“You wish to go back?” she asked.

“Yes,” he said. Then, after a second: “Maybe… not alone.”

Her heartbeat stumbled.

She looked at him.

He looked at her.

He set his cup down on the step.

“Greta,” he said.

She’d never heard her name spoken like that. Not barked across a ward. Not hissed in fear. Just… said. Like it was something worth holding gently.

“I…” he cleared his throat, suddenly aware that his German was not up to this. “Ich… möchte…” He frowned, flipped the dictionary pages, then gave up and switched to English, his voice low and earnest.

“I don’t know… all words,” he said. “But… would you… think about… coming to America?”

Her breath caught.

“What?” she whispered.

“Not now,” he said quickly. “When… Krieg—war… is over. When papers, okay. Come with me. To Iowa. My home. My farm. My… family.”

His cheeks flushed.

“I am not… asking now to marry,” he added, stumbling. “Not yet. But…” He groped for the phrase. “I think. Ich glaube… we could… have a life. Together. If you want.”

She felt like someone had opened a window in a room she hadn’t realized was full of smoke.

America.

Iowa.

A farmhouse in fields that went on forever, nothing falling from the sky but rain and snow.

She’d never even left Germany, except in the worst possible way—in the bodies of men she’d treated from Russia and Italy and France.

“You… you want… me?” she asked, barely audible.

“I want… you,” he said simply. “Not… just nurse. Not just German. You, Greta. The way you… hold men’s hands when they die. The way you… laugh, sometimes, when you think no one hears. The way you work. Hard. And how you… look at me. Like I’m not… monster. Or… hero. Just… man.”

Her throat was tight.

She reached out, almost without thinking, and took his hand.

Her fingers closed around his.

It was the smallest gesture.

It said everything.

They weren’t the only ones.

War had a way of pulling people together fast, like gravity increased around the edges of trauma.

Leisel and Robert.

She was twenty, hair braided tight, eyes that had seen too much. He was a radio man from Queens, Italian-American, with a grin that could have lit up a blackout.

He started by leaving extra sugar packets on her tray. A can of peaches. A clean handkerchief tucked into the pocket of her apron.

“You’ll get court-martialed,” his bunkmate had warned.

“Then I’ll at least have done something worthwhile first,” he’d replied.

One evening, he took her for a walk around the hospital grounds.

The ruins made the path uneven. They picked their way carefully over broken cobbles and around craters.

Under a tree that somehow still had leaves, he stopped.

He pulled a scrap of paper from his pocket, smoothed it on his palm, and sketched a little church, two stick figures holding hands in front of it.

He held it up, heart pounding.

“Will you…” he pointed at the drawing of her, then at himself, then mimed a veil and a ring. “Marry?”

She understood enough.

Her hands flew to her mouth.

Then she flung herself at him, words pouring out in rapid German he couldn’t catch.

“Ja,” he heard, over and over.

Yes.

Katarina and Edward.

She was in her mid-thirties, head nurse, lines around her eyes, posture straight as a yardstick. She’d kept entire wards running on two syringes and a bottle of iodine. Men feared and respected her in equal measure.

He was a quiet medic from Pennsylvania, older than most—twenty-eight—with a widow’s peak and a patience that seemed bottomless.

He watched her move through the hospital for weeks before he approached her.

When he did, he handed her a small velvet box.

Inside was a ring, simple gold band, worn but polished.

“It… was my mother’s,” he said slowly, using the German words he’d carefully practiced. “Sie… starb. Died. In ’42. I think… she would like… if you wear it.”

He took a shaky breath.

“I… liebe dich,” he added, his accent mangling the soft consonants. “Willst du… meine Frau sein?”

Will you be my wife?

Katarina’s face crumpled.

She’d spent so long being strong that she’d forgotten what it felt like to be wanted, not for her competence but for herself.

“Yes,” she said, in English and German and in the way her shoulders dropped as if someone had finally taken a burden off them.

Around them, more such stories unfolded.

Sophie and Daniel.

Emma and Michael.

Clara and David.

Each pair found their way differently. A shared joke over a mispronounced word. A hand steadying an elbow when a stair crumbled. A letter pressed into a palm.

The hospital staff started calling it “the epidemic,” half-teasing, half in awe.

This fever brought rings instead of rashes.

Regulations didn’t like any of it.

Fraternization was technically forbidden.

The rules had made sense when they’d been drafted—before the surrender, before occupation, before anyone had thought about what it would mean to have hundreds of thousands of young men in close proximity to a defeated, traumatized civilian population.

Now those rules ran headlong into reality.

Captain Morrison, the same doctor who’d been unmoved by blood and gore for a year, found himself sitting across from James and Greta in his small office, listening to something he’d never expected to hear in a war zone.

“We want to get married, sir,” James said.

Greta sat beside him, hands folded in her lap, back straight, eyes steady.

Morrison looked at them.

“You’ve known each other… how long?” he asked.

“Three weeks,” James said. “Since the hospital was secured.”

“Three weeks,” Morrison repeated. He rubbed his temples. “You know there’s a whole manual about why this is a bad idea, right?”

“Yes, sir,” James said. “I’ve read it.”

“But you still want to do this.”

“Yes, sir.”

Morrison looked at Greta.

“Why?” he asked bluntly.

Greta chose her words carefully, reaching for every bit of English she’d learned.

“Because…” She paused, searching. “Because there is… nothing here, for me. No Familie. No Haus. No… Zukunft.” She waved her hand toward the window, toward the broken skyline. “Germany is… kaputt. Broken. James is… gut. Good. He… sees me. Not only… nurse. I want…” She swallowed. “I want a… Leben. Life. With him. In… Iowa.”

Morrison sat back.

He’d seen what the war had done to these women.

He’d seen the way they flinched at loud noises, the shadows in their eyes when someone mentioned certain places. He’d seen their hands—steady over scalpels, shaking over coffee cups.

He’d also seen what the Americans did to them without meaning to—smiles, extra rations, small kindnesses that cracked open something long sealed.

He thought of his own wife, back in Chicago, of the letters they’d traded.

He thought of the regulations sitting on his desk, written by men in offices who’d never watched a German nurse cuddle an orphaned infant with the same care she’d used to hold a dying infantryman’s hand.

“Technically,” he said slowly, “this is against regs.”

James’s shoulders tensed.

“But practically,” Morrison went on, “if I send you away from each other, you’re going to spend all your off-duty hours trying to sneak back in. You’re going to be less effective at your jobs. Greta’s going to face a future here that… frankly, makes my stomach hurt to think about. And the occupation’s going to lose two people who actually give a damn about making this place better.”

He sighed.

“Which means,” he finished, “I’d be a damned fool to stand in your way.”

He pulled a form from his drawer and slapped it on the desk.

“Here,” he said. “Marriage request. Fill it out. I’ll sign. Chaplain’ll grumble. My CO will pretend to yell. And then he’ll sign too.”

James blinked.

“Sir—”

“Don’t make me regret this, Carter,” Morrison said gruffly. “If you turn out to be a heel, I’ll find you in Iowa and rearrange your teeth.”

James’s grin was blinding.

“Yes, sir,” he said. “I mean—no, sir. I mean—”

“Get out of my office,” Morrison said, fighting a smile. “And tell Robert and Katarina and whichever other lovesick idiots are lurking in the corridor that it’s case-by-case, not a blanket policy.”

James and Greta left in a rush, hands linked.

Morrison stared after them.

Then reached for his pen.

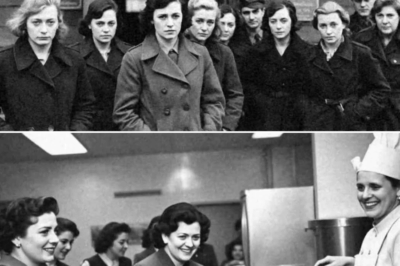

The weddings happened fast.

Word spread through the hospital—“the Americans are marrying the nurses”—and for a few days, the chapel and any spare room that could be decorated with pilfered flowers became scenes for makeshift ceremonies.

The first was Greta and James.

It was held in what had once been the hospital’s pediatric ward. Someone had found a vase. Someone else had found a scrap of white fabric to drape over the plain table that served as an altar.

The chaplain was a Methodist from Kansas who’d married farm couples in small-town churches before the war and prisoners in muddy fields during it. He stood in a uniform that still smelled faintly of wool and dust and opened his worn Bible.

Greta wore a borrowed dress—simple, light-colored, a little too big at the shoulders. Her hair, usually pulled back in a severe bun, fell in loose waves around her face.

James stood opposite her in his Class A uniform, the creases not as sharp as they’d been when he’d left Iowa but present nonetheless. He’d polished his shoes until they reflected the flickering electric light.

They held hands.

The chaplain spoke in English and then, for Greta’s benefit, in slow, careful German, phrases he’d practiced.

“Do you, James Carter, take this woman, Greta Müller, to be your lawfully wedded wife,” he said, “to have and to hold, in peace and in war, in sickness and in health, for as long as you both shall live?”

James’s voice didn’t wobble.

“I do,” he said.

“And do you, Greta Müller,” the chaplain asked, “take this man, James Carter, to be your lawfully wedded husband, zu lieben und zu ehren, to love and to honor, for as long as you both shall live?”

Greta looked at James.

At the way his eyes shone.

At the way his hand squeezed hers just once, reassuring.

“I do,” she said.

“Then by the authority vested in me by the United States Army and the grace of Almighty God,” the chaplain said, smiling, “I now pronounce you husband and wife. Ihr seid jetzt Mann und Frau.”

Later, when they stepped out into the corridor, their colleagues showered them not with rice but with whatever they had—paper scraps, dried flower petals, laughter.

Katarina’s wedding to Edward was quieter, held in a small town church that still had half its roof. The local pastor, his eyes still hollow from years of watching his congregation thin, co-officiated with the American chaplain.

Leisel and Robert’s ceremony took place under that same tree with the leaves, the sketched church tucked into her apron pocket, later turned into a proper ring when he could afford one.

Emma and Michael.

Sophie and Daniel.

Clara and David.

Each one added a thread to the tapestry of something new weaving itself inside the husk of what had been.

Paperwork tried to catch up.

Forms multipl ied.

The U.S. Army wanted to know everything about these German women joining American households.

Where had they lived?

Had they been members of Nazi organizations?

Had they attended rallies?

Had they denounced anyone?

What had they done in this war beyond bandaging and comforting and cleaning?

Greta sat in a makeshift office one afternoon, hands folded in her lap, as an intelligence officer in glasses asked questions through an interpreter.

“Were you ever a member of the National Socialist Party?” he asked.

“No,” she said.

“Did you ever work for the Gestapo, the SS, any political organizations?”

“No. I worked in hospitals. Always.”

“Did you ever report anyone—colleague, patient, neighbor—to the authorities?”

Her jaw tightened.

“Yes,” she said, after a long pause.

The officer’s pen stopped.

“Explain,” he said.

“A man came in,” she said slowly. “1942. Wounded. He spoke… badly… about Hitler. In the ward. Loud. The Sister Oberin—head nurse—heard him. She reported. Not me. But I…”

She swallowed.

“I did nothing,” she said. “I did not stop her. I did not tell the doctor to lie. I was… feig,” she said. “Coward.”

The officer studied her.

“You continued to treat his wounds,” he said.

“Yes.”

“You did not testify against him?”

“No.”

He made a note.

The questions continued.

They weren’t clean. Nothing about the last six years was.

But in the end, the Army decided that nurses who’d spent the war wrestling with amputations and infections and bombs were, on balance, more asset than threat.

Clearance was granted, grudgingly.

Greta tucked the stamped paper into a folder that now held, neatly, her marriage certificate and her exit documents.

The day the ship left Germany, the weather matched their mood.

Low clouds. Cold wind cutting across the harbor.

Greta stood at the rail with James’s arm around her shoulders and watched the shoreline of a country she’d thought she’d die in recede.

Behind them: rubble, graves, ghosts.

Ahead: something she couldn’t picture except in fragments—fields, a farmhouse, a kitchen with a table big enough for children, a bed that creaked for reasons having nothing to do with pain.

Around them, other newlyweds clustered—Leisel leaning into Robert, her face pressed into his jacket; Katarina standing straight beside Edward, one hand clutching the rail and the other tangled with his; Emma, Sophie, Clara, and the others, all carrying two lives in their chests, old and new.

“You’re sure?” James murmured at her ear as the shoreline shrank.

Greta didn’t answer right away.

She thought of the hospital corridor she’d walked down every day of the war, walls closing in with the weight of suffering. She thought of the nights she’d slept sitting in a chair because there weren’t enough cots. She thought of the moment when silence had fallen, and instead of relief, she’d felt only emptiness.

She thought of her parents’ faces, half-forgotten dreams of a future that had ended in fire.

Then she thought of James’s hand reaching for hers on the hospital steps.

Of the first time she’d tasted real coffee again.

Of the rough, precious little ring he’d bought in a market from a man selling trinkets and memories.

She turned to him.

“I am sure,” she said.

She set her jaw.

“I do not look back,” she added in her careful English. “I come… nach vorne. Forward. With you.”

He kissed her forehead.

“Welcome to the crazy path, Mrs. Carter,” he said.

She smiled.

Mrs. Carter.

It sounded like a name that belonged on a mailbox at the end of a long gravel driveway, not on a door in a bombed-out German city.

She decided she liked it.

America was loud.

And big.

Greta had expected that.

She hadn’t expected how… intact it all would be.

Houses with roofs. Shops with actual goods on the shelves. People who hadn’t learned to flinch at airplane engines.

In Iowa, the fields James had mimed finally made sense—endless rows of corn, stretching to a horizon that was flat and forgiving.

His family welcomed her cautiously at first.

A German daughter-in-law born of a war they’d followed from newspapers and telegrams.

She cooked sauerkraut and learned to like apple pie.

She learned English from neighbors, from radio shows, from the lip movements of her children as they babbled.

She wrote letters back to Leisel in New York, to Katarina in Pennsylvania, to Emma in Ohio, comparing notes on strange American customs and the ways their husbands missed home without meaning to.

Sometimes, when tornado-season winds rattled the windows, she’d wake sweating, certain she’d heard bombs.

James would pull her close and murmur, “Just thunder, Grete. That’s all.”

She’d eventually fall back asleep to the sound of rain on the roof, grateful.

Years later, when their eldest daughter asked, “Mama, why did you come here?” Greta would tell her a version of the story.

“The war was over,” she’d say, folding laundry. “Germany was… broken. Your papa was… good. And he said, ‘Come with me. We can build something new.’ So I said yes.”

The daughter would roll her eyes.

“Romantic,” she’d say.

Greta would smile.

“It was,” she’d reply. “And it was practical. Which is the best kind of romance.”

The story of Greta and James, of Leisel and Robert, of Katarina and Edward and the others, became one thread among many in the tapestry of postwar history.

Official histories didn’t dwell on them.

They focused on conferences and treaties, occupations and airlifts, the Cold War’s chill.

But in family albums across America and Germany, in faded photos of young women stepping off ships with tired smiles, in letters tied with ribbon in attic boxes, another story lingered.

A story about young men who’d learned more about death than any twenty-year-old should and chose, when they could, to offer life instead.

About young women who’d watched their world burn and decided, when given the chance, to walk toward something new instead of sitting in the ashes.

About how, in the quiet aftermath of the loudest war in history, hope sometimes arrived not with flags and speeches but with a shy question on a hospital step:

“Will you come with me?”

And a hand reaching back, saying in every language that mattered:

“Yes. I will.”

THE END

News

Amidst the chaos, they set up a makeshift aid station in a church displaying a prominent red cross, treating wounded soldiers from both sides of the conflict.

The Red Cross in the Storm The jump had gone wrong from the start. One moment, Ken Moore was standing…

German “Comfort Girl” POWs Were Astonished When American Soldiers Respected Their Privacy

The Day the Monsters Had Rules Schroenhausen, Bavaria April 1945 The engines came first. Margaret Miller pressed her forehead to…

My husband left us for his mistress—and three years later, I met them again. It was unbelievable, but satisfying.

After 14 years of marriage, two children, and a life I thought was happy, everything collapsed in an instant. How…

The Dishwasher Girl Took Leftovers from the Restaurant — They Laughed, Until the Hidden Camera Revealed the Truth

Olivia slid the last dish from a large pile into the sanitizer and breathed a sigh of relief. She wiped…

German Women POWs in Oklahoma Were Told to Shower With Water — And Burst Into Tears

Story title: The Day the War Fell Off Their Skin Camp Gruber, Oklahoma April 1945 The truck came in on…

“Are There Left Overs?” Female German POWs Were ASTONISHED When They First Tasted Biscuits and Gravy

Story title: Biscuits and Mercy Camp Somewhere in the American Midwest Late 1944 The first thing they noticed was the…

End of content

No more pages to load