Story title: Open Doors

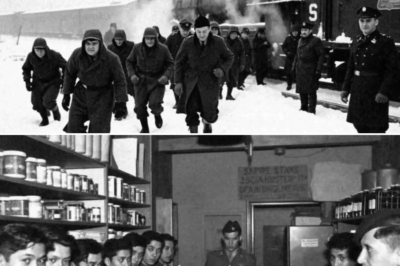

1944

Somewhere in the American Midwest

When the tailgate dropped, the air didn’t smell like war.

It smelled like coal smoke and cold iron, with a faint trace of coffee drifting from somewhere inside the train station.

Margarete “Greta” Weiss squinted against the winter light and hesitated at the edge of the truck bed. Her boots were stiff, her uniform loose on a body that had forgotten what it meant to feel full. The others crowded behind her—clerks, radio operators, typists, nurses—field-gray skirts and jackets that no longer fit as they should.

“Los,” one of the American guards said, gesturing. “Down you go.”

He didn’t jab them with the barrel of his rifle. He didn’t shout anything but that one word. His tone was firm, bored.

Greta climbed down.

The ground crunched underfoot—packed snow over cinders. Her breath puffed in front of her face, mingling with the steam from the locomotive hissing on the next track.

She braced herself instinctively.

For jeers. For stones. For the faces of American mothers whose sons had died in places she’d only seen as colored arrows on maps.

Instead, no one was there.

Just the empty platform, the dark mouth of the station, and a single U.S. Army lieutenant with a clipboard.

He flipped a page, ticked off a number, and nodded to the guards.

“All right, ladies,” he said. “Here’s your tickets.”

He handed a stack of cardboard rectangles to one of the MPs, who passed them down the line. When Greta’s turn came, she took hers carefully, as if touching it might trigger some trap.

“Find a seat,” the lieutenant said. “You’ll be changing trains in Chicago. Don’t miss your transfer.”

He could have been talking to any group of passengers.

Greta stared at the ticket in her gloved hand.

She had expected shackles.

She got a seat assignment.

Inside the station, the world turned stranger.

The heat hit her first—a wave from the big iron stoves at either end of the waiting room. The air smelled of wet wool, cigarettes, and something sweet from the concession stand.

People filled the benches.

Women in fur-trimmed coats with children dangling from their hands. Men in suits reading newspapers. American soldiers in olive drab, caps tilted back, duffel bags at their feet.

Greta paused, her group bunching up behind her.

No one looked up in horror.

A few people glanced over, eyes taking in the unfamiliar uniforms, the “PW” stenciled on their coats. Then they went back to their papers, their conversations.

The guard with the tickets waved them forward.

“This way,” he said. “Second coach from the back. Any open seat.”

They walked.

Past a woman fussing with her toddler’s mittens.

Past a man asleep with his hat over his face.

Past a small boy staring at them with open curiosity until his mother tugged his sleeve and murmured something that made him sit straighter and offer them a shy smile.

Greta felt disoriented.

Back home, captured enemies had been paraded through streets with their hands bound and their heads down. Children had thrown stones. She had thrown a few herself when she’d been small enough to believe everything on the radio.

Now she walked through a crowd of “enemies,” and the only stones in sight were the ones in the walls.

On the platform, as they waited to board, Elfriede leaned close.

“If we wanted to,” she whispered, “we could just… walk away.”

Greta’s heart skipped.

It sounded insane.

But as she glanced around—the guards chatting near the baggage cart, one of them stamping his boots to keep warm—the realization settled in.

There were no chains. No dogs straining on leashes. No ring of rifles pointed at their backs.

Just a ticket in her hand and a train with open doors.

She looked out at the street visible beyond the station entrance. Cars slid past on slushy roads. A woman in a red hat hurried by with a shopping bag. A neon sign over a drugstore flickered “COLA” in red and white.

“If we walked away,” she said quietly, “where would we go?”

Elfriede’s mouth tightened.

She didn’t answer.

The train rocked them west.

Greta sat by the window, shoulders hunched, the ticket stub tucked into her pocket like a talisman. Elfriede sat beside her. Across the aisle, two other women from their group—Hanna and Lotte—argued softly about whether the Americans were clever or crazy.

Outside, the landscape slid by.

At first it was snow-dusted towns with clapboard houses and neatly painted porches. Each little town had a church spire, a main street, a cluster of lights glowing against the winter gray. Kids walked along sidewalks in coats that looked warm. Women carried bags from shops whose windows held produce and goods, not “Sold Out” signs.

Then the towns gave way to fields.

Miles of them.

Flat and white now, but you could tell where the rows would be when the thaw came. Barns stood solid against the sky, their paint peeling but their roofs intact.

Smoke curled from farmhouse chimneys.

No bomb craters. No walls blown out. No skeletons of buildings lining the horizon.

Greta’s hands clenched in her lap.

She thought of Cologne, where she’d last seen her brother. Of streets turned into trenches of rubble, of facades standing with nothing behind them. Of whole blocks so pulverized that you couldn’t tell where one house had ended and another begun.

She pressed her forehead to the glass.

On the glass, in faint reverse, she could see her own reflection.

Eyes ringed with shadows. Cheeks hollow.

Behind that, the reflection of a neon sign sliding by outside.

“BOB’S DINER” it proclaimed in cheerful blue and pink.

She’d seen propaganda leaflets dropped by Allied planes before she’d been captured—photos of grocery stores full of food, headlines about American production.

The party had told her they were lies.

The fields outside did not look like lies.

A woman a few rows back murmured in German, voice trembling, “If this is their country when it is at war…”

“…what is ours?” another finished.

That night, in the camp years later, someone would pass Greta a notebook. She would write in cramped handwriting, That train ride broke my faith more than any leaflet ever could. We had been told they were starving. We saw their farms.

At a small-town station in the middle of nowhere—she never knew the name, only that the sign flashed by so fast she couldn’t read it—the train slowed, then stopped.

Steam hissed. The conductor’s call echoed down the platform.

“Ten minutes! Stretch your legs!”

Doors clattered open.

American civilians stepped down, some heading for the station house, others just pacing along the platform.

One of the U.S. guards stuck his head into their car.

“All right, ladies,” he said. “You want some fresh air, go ahead. Stay close. Train leaves without you if you’re not back.”

He sounded like a harried father on a long family trip.

Greta stared.

“You mean… we can… leave the car?” she asked cautiously through the interpreter.

The guard shrugged.

“Yeah,” he said. “Rule is you don’t leave the platform. That’s it.”

Hanna stood.

Her legs wobbled from hours of sitting.

She set her jaw, squared her shoulders, and walked to the door.

Greta followed, her heart beating a little too fast.

They stepped onto the platform.

Snow crunched underfoot again. The air was sharp, clean, filled with the scent of coal and something greasy from the station diner.

A man in an apron leaned out a door with a tray of paper cups.

“Coffee! Nickle a cup!” he called.

Another stood at a vending stand with a glass case full of cigarettes, candy, gum. Behind him, shelves held magazines, newspapers, bottles of soda stacked like jewels.

Hanna’s eyes widened.

“Das ist…?” she started.

“America,” Elfriede said faintly. “Apparently.”

A little boy, holding his mother’s hand, stared at Greta’s coat with the PW on the back.

“What’s that mean?” he asked, tugging.

“Prisoner of war,” his mother said quietly. “From Germany.”

He looked up at Greta’s face.

She expected fear.

Hate.

He frowned.

Then, very solemnly, he untwisted the paper wrapper on a piece of candy he’d been hoarding, and held it out to her.

“For you,” he said.

She didn’t take it at first.

Her hand shook.

“Danke,” she murmured finally, and took it, the sweetness crinkling in her palm.

He beamed.

His mother moved him along.

Greta stood on the platform, feeling the cold creep through her boots, the candy like a small hot coal in her hand.

If she wanted, she realized, she could walk away.

The station had doors that led out to the street. There were alleys. Trees. A whole world beyond the tracks.

She imagined stepping through those doors.

Imagined making it to the street.

Then… what?

She didn’t speak English beyond the phrase book basics. She didn’t know the currency. She didn’t know how far it was to the next town. Every face would be foreign. Every sign illegible.

In Germany, someone disappearing into the countryside might find an aunt or a cousin or a sympathetic farmer to hide them.

Here, she was a stranger.

And America, she realized, was watching in a way that differed from barbed wire.

The ticket in her pocket was both freedom and leash.

“Come on,” Hanna said softly. “The train…”

The whistle blew.

Greta looked down at the candy one more time.

Then closed her fist around it and stepped back onto the car.

There were escapes, of course.

A few women slipped away at stops, hearts pounding, disappearing into unfamiliar streets.

A handful vanished during transfers between camps and work details.

One pair from Greta’s convoy broke away during a camp visit to a nearby cannery. They hid in a hay barn two nights, living on stolen apples, then walked to the nearest farmhouse and knocked on the door, exhausted and half-frozen.

An American farmer opened it.

He took in their faces, their thin coats, the foreignness in their posture.

He could have slammed the door.

He could have reached for his rifle.

Instead, he said, “You look hungry,” and opened wider.

He fed them stew that tasted of beef and onions and kindness.

He let them sleep in the spare room, under quilts his wife’s mother had sewn.

In the morning, he drove them back to the nearest police station.

They went willingly.

Greta heard the story later in camp, passed along in whispers.

“They could have stayed,” someone said.

“And then what?” another replied. “Work on the farm forever? Hide from everyone? At least this way… we know what the rules are.”

The stories bled into each other.

An escapee caught by a sheriff miles from any camp, who gave him sandwiches before handing him over.

A girl who tried to ride a freight train, fell, broke her leg, and was brought back to the infirmary by the same men who’d been guarding her.

Each one chipped away at the sharp edges of the enemy in Greta’s mind.

The propaganda had warned them Americans were lawless. That only the Reich had order.

Here, order came with form numbers and clipboards, with Geneva Convention paragraphs quoted by men who had grown up on farms and in city tenements.

It wasn’t always fair.

But it existed.

On the long ride to Kansas, one of the guards sat in the front of Greta’s car, hat over his eyes, boots propped on the heater grate.

He spoke to the interpreter occasionally.

Mostly, he just stared out the window, like the prisoners.

Greta watched him surreptitiously.

He looked young.

Younger than some of the boys she’d seen drafted back home in ’43.

His hair curled around his ears. His jawline still had a softness to it.

He caught her looking once.

She dropped her eyes, heat creeping up her neck.

He said something in English to the interpreter.

The interpreter nodded, then turned to the row of women.

“He says his brother was killed in Italy,” he translated. “He… wants you to know that. But also… he wants you to know that he will follow the rules about prisoners. That is… his job.”

Greta blinked.

She didn’t know what to do with that information.

Her own cousin had died in Stalingrad.

Her neighbor’s son had vanished at Kursk.

Pain wasn’t a national monopoly.

She nodded slowly.

“Danke,” she said.

The guard didn’t answer.

He just settled his hat lower and stared out at America.

By the time the train reached their destination, the shock had dulled into a strange, uneasy acceptance.

The camp—rows of barracks, watchtowers, fences—felt almost familiar after the oddness of the open rails.

Inside, routines took over.

Work details, bed inspections, roll calls.

Yet even there, normality kept intruding.

Once, during laundry duty, Greta stood at a camp sink, hands buried in warm, sudsy water, scrubbing a shirt that smelled of sweat and whatever soap the Americans issued.

She caught herself humming.

It was a lullaby her mother had sung years ago when the world had still made sense.

She looked up, expecting someone to bark at her, to tell her there was no room for music here.

Instead, the American woman at the next sink—one of the WACs assigned to camp support—grinned.

“Nice tune,” she said in mangled German. “My Mutter—mother—sings also. Different song. Same… feeling.”

Greta smiled back, small.

They returned to their scrubbing.

On Sundays, a chaplain held services—Protestant, Catholic, mixed.

Sometimes German prisoners went, if only for the chance to sit in a place where people spoke softly for an hour.

Once, a child from the nearby town came with his family. Afterward, he shyly approached the fence with his father.

He had a wrapped chocolate bar in his hand.

He pushed it through the wire to Greta, who happened to be closest.

“For you,” he said.

She took it, throat too tight to say anything in any language.

Later, in the barracks, she unwrapped it and broke it into tiny squares, sharing it with the women around her.

They ate in silence, the taste of cocoa and milk and sugar almost too much.

“I thought chocolate was… over,” Lotte said, licking a smear off her thumb. “Finished. Bombed.”

“Not here,” Greta said.

She didn’t sound bitter.

Just bewildered.

Years later, back in a Germany that had been divided and rebuilt and stitched back into some semblance of normal, people would ask Greta what she remembered most about her time as a prisoner in America.

“Were you behind barbed wire?” they’d ask.

“How were the guards?”

“Did they feed you?”

“Yes,” she’d say to all of it.

She’d tell them about the barracks and the work, the boredom and the letters home.

But if they pushed, if they were family or friends and not just curious acquaintances, she’d tell them about the train.

About the open doors.

About standing on a platform in a nameless town with snow under her boots and a train behind her and the vastness of America in front of her—and realizing that the enemy trusted her enough to let her stand there without a gun at her back.

That trust had been calculated, of course.

She knew that now.

America hadn’t been naive.

It had been confident.

Confident enough to say, Go ahead. Take a deep breath. Look around. You’re still not going anywhere.

It had been a strange kind of mercy.

One that said, We are so certain of this place and its rules and our ability to find you again that we can afford to let you stretch your legs.

That freedom, she would say, had tasted as unsettling and intoxicating as the first chocolate bar through the fence.

Maybe, she’d add quietly, that was the point.

“We were raised on fear,” she’d say to her granddaughter once. “Fear of enemies. Fear of what they would do to us. Then we took a train across their country and saw shops and children and fields and people who did not look at us like we were animals.”

Her granddaughter would frown.

“And that… changed you?”

“It changed everything,” Greta said. “Bombs ended the war. But those open train doors…” She trailed off, searching for words. “They ended something inside of us, too. The belief that the world was only what we had been told.”

She thought of a moment she rarely spoke of—the fleeting temptation to step off that platform and just walk, to see how far her legs would take her before someone noticed.

She’d stayed.

Not out of obedience.

Out of understanding.

It was a realization she carried like a small, heavy stone:

The land you walked through, the way the enemy treated you when you were powerless—that told you more about a nation than any flag ever could.

America’s greatest weapon, she sometimes thought, hadn’t been the ship or the bomb or the rifle.

It was the quiet confidence to let a train full of enemies roll unchained through its heartland—

And to know that what they saw through the windows would do the talking.

News

A Truth That Has Been Silenced For 50 Years. The Secret Of The Concentration Camps

Number 13 Buchenwald, 1943 They always came in the evenings. Fifteen minutes at most, sometimes less. They never stayed longer…

Japanese POWs Broke Down After Tasting Hamburgers and Coca-Cola in American Camps

The Taste of Fat Camp McCoy, Wisconsin Winter 1944–45 By the time the train shuddered to a stop, Hiro Tanaka…

Female German POWs DREADED Black American Soldiers Until This Happened

The Red Cross in the Storm The jump had gone wrong from the start. One moment, Ken Moore was standing…

When the defense ended, Professor Santos came to shake hands with me and my family. When it was Tatay Ben’s turn, he suddenly stopped, looked at him carefully, and then his expression changed.

When the defense ended, Professor Santos came to shake hands with me and my family. When it was Tatay Ben’s…

She protected 185 passengers in the sky — and moments later, the F-22 pilots said her call sign out loud… revealing a truth no one expected..

She was just another face in the crowd, tucked away in seat 14A. To the casual observer, she was entirely…

The mafia boss’s baby wouldn’t stop crying on the plane—until a single mother did the unthinkable

Dominic’s head snapped toward Sarah. His gaze hit her like a physical force. “A nurse,” he repeated lowly. “And what…

End of content

No more pages to load