In the last days of the war, when Germany was nothing but smoke and road dust, a nineteen-year-old named Lukas Schneider stood in a field in Bavaria and waited to die.

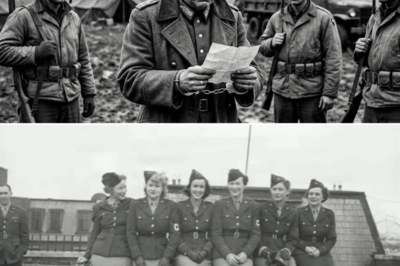

He had his hands clasped behind his head, fingers numb from cold and fear. Around him, roughly three hundred German soldiers stood in a long, ragged column, watched by American riflemen who looked, to Lukas’s eyes, impossibly relaxed. The field smelled of damp earth and sweat and the sour tang of unwashed wool. Somewhere a truck engine idled.

Everything he had been told said this was the end.

For two years, ever since he had been conscripted at seventeen and pulled from his father’s carpentry shop in a Bavarian village so small it didn’t appear on most maps, the message had been the same: The Americans don’t take prisoners.

Officers passed around photographs of Allied “atrocities” at the front. Training sergeants described GIs cutting dog tags from bodies, ears from heads, throats from anyone too slow to answer. They spoke with special venom about black American units and Jewish soldiers, insisting they were driven by hatred, eager for revenge. Surrender, they said, was worse than death. If capture was unavoidable, a bullet in your own head was honorable. The Wehrmacht would call it heldentod—a hero’s death.

Lukas’s older brother, Friedrich, had believed that. Near Aachen, facing encirclement, he had put a pistol in his mouth rather than raise his hands.

Now Lukas stood in a field and tried not to think about his brother, tried not to think about his mother and two sisters, about his father, killed in a bombing raid in 1944, about the tables he had hoped to build one day.

He braced for the sound of bolts being drawn back in unison.

Instead, he heard a voice speaking German.

“Wasser. Ihr bekommt Wasser. Zwei Reihen bilden.” Water. You’ll get water. Form two lines.

He jerked his head up. The man shouting was an American soldier, but the German came out crisp and clean, like a native speaker’s. Another GI slogged forward with a water barrel, hoisting it down from a truck with a grunt.

“Is that before or after the torture?” someone muttered behind Lukas’s shoulder.

The American with the barrel looked up. His eyes moved along the line of gray coats and hollow faces. “It’s just water, kid,” he said in German. “We’re not monsters.”

He smiled. It was a tired smile, but it was a smile.

Lukas’s throat burned. He stepped forward and took the tin cup held out to him. The water was shockingly cold and clean. He drank greedily—and vomited almost immediately, his empty stomach rebelling.

He flinched, expecting laughter or a blow.

The American refilled the cup and held it out again. “Langsamer dieses Mal,” he said. Slower this time.

Later, much later, Lukas would think of that moment as the first crack in the shell he’d lived inside for years.

They drove for six hours.

The trucks smelled of oil and men crammed too close together. Some tried to pray. Others sat blankly, too numb even for fear. Lukas watched the landscape change through a flap in the canvas. Fields and farms, then paved roads, and finally something he never expected to see in a place that was supposed to be his grave: a baseball field.

The convoy pulled into Camp Concordia, Kansas.

Guard towers, barbed wire, rows of white barracks—nothing surprising there. But in the yard beyond the wire, German prisoners in work clothes were kicking a ball, playing cards, lounging on benches as if they were in a strange, rough version of a village square.

As Lukas climbed down from the truck, his legs shaking, he caught snatches of conversation. English and German mixed together. Reluctant laughter.

The guards were young. Many didn’t look much older than he was. Their rifles were slung over their shoulders, not held ready. “Move it along, boys,” one said in halting German. “Camp’s not going to process itself.”

There was no lineup at the edge of a pit. No shouted orders to kneel. Instead, there was paperwork.

Name. Rank. Serial number. Unit. A medical exam in a low building that smelled of disinfectant and tired bodies. A doctor checked for lice, for trench foot, for the shadows of malnutrition around eyes and gums. He did it without a sneer, without a backhand.

Delousing. A shower. A rough but clean uniform—American surplus dyed and stamped “PW.” A bunk assignment. A schedule.

At 1800 hours, Lukas was herded with the others into a mess hall. The smell inside—stew, potatoes, something fried—made his eyes sting. He expected a ladle of thin soup, a slice of bread at best. Punishment food. Enough to keep them alive and miserable.

Instead, a cook with a stained apron grinned ruefully as he dropped a scoop of something thick and meaty onto Lukas’s plate.

“Not good food,” he joked, his German clumsy. “But food.”

There was more on the plate than Lukas had eaten in a week. He stood, eating as fast as he could, half-convinced someone would snatch the tray away. No one did. No one struck him. No one laughed when he spilled a little gravy with his shaking hand.

He went back to his bunk that night and lay awake, staring at the wooden slats above his head.

I might survive this, he thought, and the idea itself was terrifying.

James Walker drew recreation yard guard duty on his second day at Camp Concordia.

He was twenty, tall, shoulders already a little stooped from years on an Iowa farm. He had expected to be sent to the Pacific. Instead, a set of orders had landed him in Kansas, watching over Germans kicking a ball.

His grandparents had come from Bremen in 1891. He’d grown up hearing rough German at the dinner table—Guten Morgen, danke, komm her. After Pearl Harbor, speaking German in public had become something you didn’t do. Here, it was suddenly useful.

“Baseball,” he said, holding up the ball in his hand in the yard one morning. “Base-ball.”

A cluster of prisoners near the fence watched warily. One, a thin boy with eyes that seemed too old for his face, repeated the word carefully. “Baseball.”

Walker grinned. “That’s it. You want to learn?”

The boy hesitated, glancing around. Someone muttered under their breath in German—maybe calling him foolish, a traitor to his own side—but he stepped forward anyway.

That boy was Lukas.

Over the next weeks, in stolen ten- and fifteen-minute snatches between chores and roll calls, Walker taught Lukas perhaps forty English words. Baseball. Thank you. Good morning. Cigarette. Home. Brother. Father. Table. Rain. Sky. Freedom.

In return, Lukas taught him that Germans were not all slavering fanatics. He taught him the word Zimmermann—carpenter—and mimed planing wood.

“My father, his father,” Lukas said one afternoon, tapping his own chest, then making a cutting motion with his hand. “I make… Tisch.”

“Table,” Walker said.

“Table,” Lukas repeated. Then, more firmly, “Good tables. Strong tables. Not war tables.”

Walker laughed and, on impulse, pulled a cigarette from his pack. His ration didn’t go far, but he knew he could get more. Lukas stared at the thin white cylinder as if it were a relic. “Why?” he asked, in rough English, pointing from the cigarette to Walker and then to himself. “Why you… friendly?”

Walker scratched the back of his neck. How did you explain the Geneva Convention to a boy who’d been raised on Goebbels and camp songs? How did you say because it’s right without sounding like you were doing your own propaganda?

“You’re nineteen,” he said at last. “I’m twenty. War’s over. We’re just people now.”

Lukas held the cigarette between trembling fingers. He thought of what he wanted to say: You were right about us. We started this. We built the camps. The words were heavy. They stuck behind his teeth.

Walker seemed to sense it and, with the ease of someone raised in a house where feelings weren’t spoken directly, steered the conversation away.

“You got family?” he asked.

“My mother. Two sisters,” Lukas replied. “Father is… tot. Dead. Bombing. Nineteen forty-four.”

“I’m sorry,” Walker said.

He said it simply, and he meant it. It hit Lukas harder than yelling would have. The country whose planes had killed his father was now represented by a young man who offered sympathy rather than contempt.

It didn’t erase anything. It did something else instead: it complicated it.

The moment that branded itself deepest came a few weeks later.

A new transport came in from France—older prisoners, more hardened. Among them was a man named Dieter, in his mid-forties, with hard eyes and an SS blood group tattoo inked under his left arm.

Even in a POW camp full of defeated men, the SS stood out. Most of the other prisoners avoided him. They knew enough of what the black uniforms had done in the east and in the camps to have their own resentments.

Dieter was sick. Pneumonia, the camp doctor said. He was also furious. He had fought the orderlies when they tried to move him, ranting about Jewish doctors and American lies about German honor. They sedated him and put him in the infirmary.

Walker was assigned to guard the door. Lukas was nearby with a broom and mop; POWs were routinely used for cleaning duties around the camp.

Through the thin wall, they heard it start.

“You are killing me!” Dieter screamed in German. “Poison! I know what you do to Germans!”

“No one is poisoning you,” came Walker’s voice, patient. “You have pneumonia. The doctor is trying to help.”

“You lie! Jewish lies!”

There was the crash of glass, the clatter of something metal breaking.

Lukas dropped the mop and edged closer to the doorway. Through the half-open door of the infirmary, he saw Dieter on his feet, swaying, gripping the jagged remains of a water pitcher as if it were a club. His hospital gown hung open over a chest that rattled with every breath. Face flushed, eyes wild.

Dr. Goldstein stood on the other side of the bed. He was small, dark-haired, wearing a lieutenant’s bars and a stethoscope around his neck. The camp’s Jewish-American doctor, who had treated Lukas’s own infected foot the week before with quiet efficiency.

He had his hands up, palms forward. “Beruhigen Sie sich,” he said in German. Calm down.

Walker stood between them.

“Put it down,” he said, not shouting, not reaching for his holster. “You’re sick. Let us help.”

“I’d rather die than let a Jew touch me,” Dieter spat.

Lukas felt something cold settle in his stomach. If Walker stepped aside, if Goldstein decided this man was not worth saving, who would blame them? For three months now, Lukas had been learning, through letters and camp newspapers, what names like Auschwitz and Treblinka meant. The pile of evidence was mounting: the neighbors who had disappeared, the trains, the chimneys, the pits. Men like Dieter had not just worn the uniform. They had enforced it.

Dieter lunged.

He didn’t get far. Fever and hunger had robbed him of strength. Walker caught his arm, twisted, and pulled him down, pinning him to the floor with an ease born of youth and farm work. He didn’t slam him. He lowered him carefully, like handling an angry child.

“Niemand bringt dich um,” he said in mangled German. “Nobody’s killing you. You are safe. Be still.”

Dieter fought for a few seconds, then broke into ragged sobs. “Ich will nicht sterben,” he cried. I don’t want to die.

“You’re not going to,” Goldstein said, kneeling. “But you need medicine. If I give it, will you take it?”

The SS man’s nod was small and miserable.

Lukas watched as Goldstein listened to Dieter’s chest again, as he prepared a syringe and slid the needle gently into the older man’s arm. He watched Walker sit back on his heels and stay there, watching, until Dieter’s frantic breathing eased into sleep.

No one made a speech. No one pointed out the irony.

Later, standing outside with a cigarette, Walker caught Lukas’s eye.

“You saw that?” he asked.

Lukas nodded.

“I know what you’re thinking,” Walker said slowly. “That guy probably did things. Things we’ll never know. Things he’d never admit. And we could have let him choke in his own lungs. But we’re not them. We don’t let people die just because we hate what they did.”

He took a drag, exhaled.

“That’s the difference.”

Three words. That’s the difference.

For a boy raised on slogans about blood and soil, those words carried more weight than any speech.

In August, the camp newspapers arrived with photographs and testimony of liberated concentration camps. Buchenwald. Dachau. Bergen-Belsen. Piles of bodies. Survivors staring at the camera from hollowed-out faces. Addresses. Lists. Train schedules.

Lukas retched in a toilet stall until nothing came up.

He had known something was wrong. Anyone with eyes had. Neighbors who disappeared. Jewish shop signs painted over. The way certain people never came back from “resettlement.” He had known enough to be uneasy. He had not known this.

When he finally stumbled outside, eyes burning, he found Walker sitting on a crate near the barracks.

“You read it,” Walker said. It wasn’t a question.

Lukas nodded, jaw clenched so hard it hurt.

“We didn’t know either,” Walker said quietly. “Not… all of it. Not how bad. Some guys in the camp units found out the hard way. I talked to one. Said the smell gets into your clothes, into your hair. You can’t ever quite wash it out.”

They sat in silence for a while.

“Why are you still kind?” Lukas burst out at last, the English words tumbling over each other. “To us? After that?”

“To you?” Walker said. “You didn’t build those places. You didn’t sign those orders.”

“I wore the uniform,” Lukas said. “I swore the oath.”

“Me, too,” Walker replied. “Different flag, same idea. You and I, we were kids with rifles. We can’t change what old men far above us decided. But we can decide who we are now.”

He paused, then added:

“You can spend your life drowned in what your country did. Or you can spend it making sure you never fall for that crap again. Nobody knows how to do it perfectly. You just have to start.”

In the autumn of 1945, word crept through the barracks that some prisoners were planning to fight again—an uprising, a doomed attempt to regain dignity by spilling blood. Three officers, still devoted to the dead Reich, had talked a handful of men into a plan: grab tools during a work detail, rush the guards, “show them Germans don’t bow.”

When Lukas heard, he didn’t hesitate. He went straight to Walker.

“There is trouble,” he said in English that had become steadier. “Stupid trouble. They want to fight. It will get people killed.”

“Are you sure?” Walker asked. “The other guys won’t like you much if this comes back to them.”

“They’re wrong,” Lukas said. “The war is over.”

The uprising was smothered before it began. The ringleaders were transferred under heavier guard. For a week, some of the other prisoners turned cold shoulders toward Lukas, muttering “Traitor” under their breath.

Walker clapped him on the shoulder. “You did the right thing,” he said simply.

It was the first time Lukas had acted for something, not merely against fear.

When his name finally appeared on a repatriation list, it was October. The war had been over for months. Germany was cut into zones. His village lay in the American sector. His mother and sisters were alive; a letter had come—thin paper, thick with relief and need.

The night before he left Camp Concordia, Walker found him in the barracks.

“I’ve got something for you,” he said.

He handed Lukas a small English–German dictionary and a photograph.

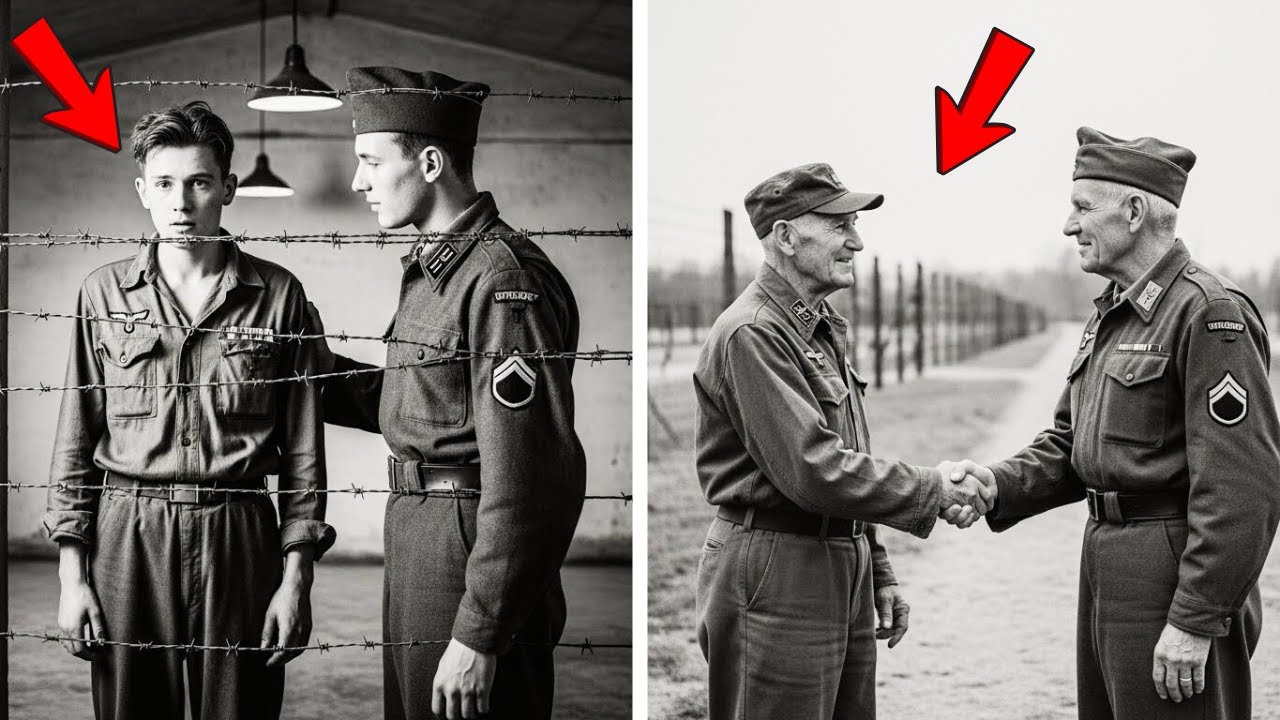

In the photo, taken on a June afternoon Lukas barely remembered, two young men sat on a bench, shoulders almost touching. One wore German trousers and an American fatigue shirt. The other wore full GI khaki. They shared a cigarette and smiled at the camera.

“This is for when things get hard,” Walker said. “So you remember not all of us were bad. And that you’re going to be all right.”

“You were not bad at all,” Lukas replied, and meant it.

“Don’t tell anyone,” Walker said. “Ruins my reputation.”

They shook hands. Lukas struggled, then pulled Walker into a brief, fierce embrace.

“Thank you,” he said. “For the water. For the words. For… making me human again.”

“You were always human,” Walker said. “You just forgot it for a while.”

Then the trucks came, and the barbed wire of Kansas disappeared in dust behind him.

Rebuilding his life in Germany was slow, and at times, crushing.

His village had survived, though his father’s workshop was rubble. His mother’s hands were rougher, his sisters older. The tools, miraculously, had been buried in a corner of the cellar. He dug them out and began to plane boards again.

But something in him had changed.

He used the dictionary to sharpen his English. He read occupation newspapers that spoke openly of guilt, trials, reconstruction. He attended lectures on democracy in a half-bombed Munich hall, where an American historian asked if there were any former soldiers willing to talk.

Afterwards, in the milling crowd, Lukas approached.

“I would like to tell you about an American,” he said. “About why I no longer believe what I used to.”

Over time, he became a kind of bridge—one of many former POWs who told students what it meant to be swept up in a totalitarian system and what it took to climb out of it. He taught civics in a local school, the kind of class that hadn’t existed when he was a boy. He talked about constitutions, about checks and balances, about propaganda and how to recognize it.

When he needed an example of the difference between following orders and following conscience, he always came back to Kansas. To one guard. To one cigarette. To a choice made in an infirmary corridor.

He married a woman who had lost her father on the Eastern Front. They had children, then grandchildren. On his desk, next to lesson plans and a well-used copy of the Basic Law, he kept the photograph and, eventually, a baseball.

In 2003, when his eldest daughter asked what he wanted for his eightieth birthday, he said, without hesitation, “To find James Walker.”

It took two years and a tangle of correspondence. Military records had to be unearthed. Addresses tracked through old phone books and cemetery registers. At last, they found a farmhouse outside Cedar Rapids, Iowa.

So in June 2005, at seventy-nine, Lukas flew back to the country where he had been a prisoner. His daughter rented a car. They drove out past fields that looked not unlike those in Kansas.

He stood on a stranger’s porch with the photograph in his hand and knocked.

An old man opened the door. White hair, still-broad shoulders. He squinted against the sun.

“James Walker?” Lukas asked.

“I go by Jim,” the man replied. “Can I help you?”

Lukas held out the photograph. “Camp Concordia,” he said. “Nineteen forty-five.”

Walker took the photo between his fingers and looked down at the two faces from another lifetime. He frowned, searching.

“I’m sorry,” he said finally, looking up. “I guarded thousands of you boys. I don’t remember you.”

The words hit like a physical blow. Sixty years of memory. A life reshaped by moments the other man did not recall.

Lukas smiled anyway.

“I know,” he said quietly. “I never expected you to. But I have remembered you every day.”

He asked, very politely, if he could tell Jim what he remembered.

They sat at the kitchen table while coffee steamed between them, and Lukas laid out the story—the field in Bavaria, the tin cup of water, the cigarette, the language lessons, the SS man on the infirmary floor, the three words: That’s the difference.

He told Jim about becoming a teacher, about lectures, about telling German students that an American guard had taught him to be human again. About carrying the dictionary and the photograph like talismans through all the years of rebuilding.

Jim listened, his eyes growing unfocused in a way that had nothing to do with age.

“I didn’t know,” he said hoarsely at last. “I thought I had an easy war. Spent it in Kansas watching you boys eat. Felt guilty about that sometimes. Figured I hadn’t done a damn thing that mattered.”

“You saved me,” Lukas said. “Not just my life. You saved me from hating you forever. From hating myself.”

Jim stood up, walked around the table, and hugged him. The embrace was careful, both of them conscious of old bones and lingering infirmities.

“Thank you for coming,” Jim said. “Thank you for telling me.”

On a shelf in the next room, there was a ball, yellowed and soft from use. He brought it back.

“I taught a lot of German kids how to throw,” he said. “Can’t remember their names. But I remember why I did it. Here.”

He placed the ball in Lukas’s hands. “Don’t put it in a glass box. Use it. Teach someone else.”

Lukas took the baseball as if it were the cigarette all over again—unexpected, undeserved, somehow exactly the right thing.

They did not see each other again.

Within six years, both were dead. Their obituaries, printed in different languages on different continents, mentioned families, work, faith, community. Lukas’s noted his advocacy for democracy and German–American understanding. Jim’s mentioned his service, his farming, his volunteer work.

Neither obituary could list all the people they influenced. No piece of paper can.

On a desk in Munich now sits that same photograph and that same baseball. Lukas’s grandson keeps them there. He coaches children—German and American—at a youth baseball clinic in a city that has long outlived the rubble his grandfather returned to.

When a nine-year-old once asked him, “Why would your grandfather’s enemy be nice to him?” he thought of two young men standing in a yard in Kansas, sharing a cigarette.

“Because sometimes,” he said, tossing the ball gently to the boy, “that’s what decent people do. Even in a war.”

And that, in the end, was the heart of it: one man’s unremembered kindness becoming another man’s lifelong compass. One ordinary act echoing quietly across six decades, shaping the way a former enemy raised his children, taught his students, and answered his grandson when the boy asked what it meant to be human.

News

(CH1) FORGOTTEN LEGEND: The Untold Truth About Chesty Puller — America’s Most Decorated Marine, Silenced by History Books and Erased From the Spotlight He Earned in Blood 🇺🇸🔥 He earned five Navy Crosses, led men through fire, and left enemies whispering his name — yet most Americans barely know who Chesty Puller really was. Why has the full story of this battlefield titan — his brutal tactics, unmatched loyalty, and unapologetic grit — been buried beneath polite military history? What really happened behind closed doors during the fiercest battles of WWII and Korea? And why has one of the Marine Corps’ most legendary figures been all but erased from modern memory? 👇 Full battle record, unfiltered quotes, and the shocking reason historians say his legacy was “intentionally softened” — in the comments.

Throughout the history of the United States Marine Corps, certain names rise repeatedly from battlefields and barracks lore. Many belong…

Woman POW Japanese Expected Death — But the Americans Gave Her Shelter

By January 1945, Luzon was on fire. American artillery thudded across the hills. Night skies flickered with tracer fire. Villages…

Japanese ”Comfort Girl” POWs Braced for Execution — Americans Brought Them Hamburgers Instead

By the last year of the Pacific War, the world those women knew had shrunk to jungle, hunger, and orders…

(CH1) Female Japanese POWs Called American Prison Camps a “Paradise On Earth”

By the winter of 1944, the war had shrunk the world down to barbed wire and fear. Somewhere in the…

6 months dirty. Americans gave POWs soap & water. What happened next?

On March 18th, 1945, when the transport train finally shrieked to a halt outside Camp Gordon, Georgia, Greta Hoffmann pressed…

(Ch1) Former Goebbels Officer Expects Torture in US Prison Camp—What He Gets Instead Breaks Him Completely

When the headline caught his eye, Eric Müller thought at first he had misread it. “President criticized for policy failures.”…

End of content

No more pages to load