At 6:43 on a raw March morning in 1943, a nineteen-year-old woman stood in a cold Liverpool basement and looked down at a painted sea.

The floor of the room in Derby House was linoleum, but to the Western Approaches Tactical Unit it was the North Atlantic. White rectangles marked merchant ships. Smaller white blocks marked their destroyer escorts. Black blocks were German U-boats. Whenever black slipped between white, red counters appeared. Red meant a ship sunk. Red meant men lost.

Janet Patricia Okell, a mathematics student turned Wren, had just completed a simulation on that floor. The pattern of chalk and counters in front of her matched almost exactly the after-action report of Convoy SC 121, which German submarines had mauled two days earlier.

Her brother had died in that convoy.

The telegram had arrived on 27 February. HMS Hesperus lost with all hands. Total loss. Thomas Okell, twenty-three years old and an anti-submarine warfare officer, had gone down with his ship in the freezing Atlantic, torpedoed while she was racing away from the convoy to chase a contact that had already slipped beneath the surface.

Three weeks earlier he had written to her from the destroyer. The tactics aren’t working, he had said. They chase the U-boats, they drop depth charges, and still the merchants are going down. Out there, in the darkness, it felt hopeless.

In the basement in Liverpool, his younger sister had been quietly proving why.

She had been posted to the Women’s Royal Naval Service in 1942 straight from her mathematics course, chosen not for any time at sea but because of the way she could see patterns in numbers that others missed. The Admiralty had sent her to a strange, unofficial unit at Western Approaches Command: the Western Approaches Tactical Unit, or WATU, an experimental outfit under Captain Gilbert Roberts that officially did not exist.

Roberts, an officer invalided out of seagoing command by tuberculosis scars, had been given an empty room, some paint, and a handful of clever young Wrens. His remit was simple and enormous: find the tactics that would beat the U-boat.

By early 1943 the Battle of the Atlantic was going badly. In February alone, German submarines had sunk sixty-three Allied ships – 342,000 tons, and more than two thousand sailors. At that rate Britain would exhaust its fuel by summer and its food by autumn. There would be nothing left to fight with.

The Royal Navy was not incompetent; it was doctrinally trapped. Two centuries of victory had been built on the principle that aggressive offence wins naval battles. Hunt the enemy, engage decisively, destroy their ability to fight. That creed had carried British ships through Trafalgar and Jutland. It made sense when both sides were fighting in sight of one another.

It made much less sense against an enemy that could disappear.

German U-boat commanders had learned to exploit British instincts. Wolfpacks operated on a simple principle: one submarine would show itself and draw the escorts off; the rest would slip through the holes that pursuit created. Each time a destroyer surged away from the convoy in a burst of star shell and depth charges, the protective screen around the merchant vessels thinned. In the open water beyond, another U-boat waited.

Janet entered this world with no preconceptions about how ships ought to fight. On the floor, she commanded the black blocks, playing the role of the German. Across from her officers straight from escort duty commanded the white counters, doing what doctrine and experience told them to do.

The first time she ran a game against a senior commander – a Jutland veteran with three decades at sea – she brought one U-boat into view on the edge of his screen. He reacted as he had been trained: two destroyers broke from formation and charged the contact. Janet let her submarine dive and creep away, while her other three counters slid into the gap the escorts had left. By the time those destroyers returned to the convoy, a dozen red markers littered the board.

The games were not academic exercises. Roberts had access to after-action reports, shipping losses and intercepted German signals. Again and again, the Wrens’ chalk battles reproduced what had already happened at sea. When escorts chased, convoys died. When escorts stayed close, presenting a tight ring of steel, the black blocks struggled to find a way in.

By the winter of 1942–43 WATU had run hundreds of such simulations. The mathematical conclusion was stark: the Royal Navy’s cherished aggressive tactics were costing ships and lives, not saving them. Roberts and his staff wrote report after report, recommending tighter defensive screens and a refusal to be drawn too far from the merchant columns. The papers went up the chain to the Admiralty and stalled there.

Floor games, some senior officers sniffed, were not real war. WATU was experimental. Battle-hardened captains knew better than girls with chalk who had never seen an Atlantic gale.

Then came SC 121 and the loss of Hesperus.

When Roberts handed Janet the telegram, he suggested she take the rest of the day. She refused. She finished the simulation she was running – in which Lieutenant Morrison, following standing orders, had again sent his escorts charging off after a decoy submarine and left his convoy in ruins – and then she asked for something that would change the course of the Atlantic war. She asked to put an admiral in the pit.

Not just any admiral, but the one man whose word could rewrite doctrine for the entire Western Approaches: Admiral Sir Max Horton, Commander-in-Chief.

It was a bold idea. Horton was a legend, one of Britain’s most successful submarine captains in the First World War. He had risen through the Fleet with the old aggressive creed in his bones. But he was also curious, and he knew that the existing tactics were not delivering the results he needed. When Roberts invited him to visit Derby House and see what his experimental unit had to offer, he came.

On 3 March 1943 Horton walked down into the basement under Derby House. He was seventy years old, thick-set, quietly formidable. Roberts explained the set-up, the painted ocean, the blocks and stopwatches, the German tactics drawn from captured documents. Then he invited Horton, politely but firmly, to take command of the escort group in their next game.

It was a subtle trap, and the admiral stepped into it willingly.

The scenario represented a typical mid-Atlantic convoy: fifty merchant ships and eight destroyers in winter conditions with poor visibility. Janet and her colleague, Wren Jean Laidlaw, commanded six U-boats between them. Horton studied the grid and arranged his white blocks around the convoy in precisely the way he had spent his career teaching: spread wide to search aggressively, ready to surge outward towards any threat.

Janet took the first move. She brought one of her submarines close enough to be detected and then let it be seen. Horton reacted instantly. A pair of destroyers broke away, as they always did, and thundered towards the sighting. In the real ocean they would have been dropping depth charges by the ton. On the floor, chalk circles marked their attack patterns.

Meanwhile, Janet’s other counters slid inexorably through the space those destroyers had vacated and into the convoy’s heart.

It was over in forty-seven minutes of game time. Seventeen merchant ships lay on their sides in red. None of the U-boats had been “sunk”. The screen had been fractured by its own offensive impulse.

Silence settled over the room. Senior officers watched the admiral for his reaction. Janet waited with her chalk in hand, aware that she had just demonstrated to the architect of Western Approaches strategy that the weapon he prized most – the aggressive spirit of his destroyer captains – could be turned against them.

Horton took off his glasses and stared at the board.

Then he did the unthinkable. “This works,” he said. “Teach every commander.”

In that moment, the weight of tradition shifted. From then on, WATU was no longer a curiosity. It was a school, and its curriculum was urgency. Every escort captain crossing the Atlantic would pass through the pit. They would command simulated convoys against the Wrens’ simulated wolfpacks and learn, often the hard way, that staying with the merchant ships saved lives and that the urge to chase had to be suppressed.

Out of the chalk and arguments emerged a new set of tactics: standing orders for tight screens, drills like “Raspberry” to light up night attacks with coordinated star shell illuminations, “Beta Search” patterns to intercept shadowing U-boats at the likely places rather than sweep futilely through empty sea. These manoeuvres were given names to help officers remember them under stress, but at their core they embodied a simple idea. The convoy was not bait. It was the vital organ that could not be exposed.

Between March and July 1943, more than 2,500 officers from the Royal Navy and other Allied navies tramped down the steps into Derby House. Some arrived sceptical, bristling at being taught by young women who had never been on a ship. Most left subdued and convinced. It is one thing to read that your methods might be flawed; it is another to watch a nineteen-year-old calmly sink your convoy again and again and show you exactly how you helped her do it.

The effect at sea was swift. In May 1943, with the first WATU-trained commanders on the North Atlantic run, U-boat losses spiked to catastrophic levels. Forty-one submarines were destroyed that month alone. For the first time, German Admiral Karl Dönitz was forced to pull his wolfpacks back from the central Atlantic. Merchant ship losses plummeted. The feared starvation of Britain receded.

Historians would later estimate that the tactical shift engineered at WATU helped save some four thousand merchant ships and nearly fifty thousand sailors in the last two years of the Atlantic war. It is a staggering number, especially when set against the small, cold basement where those tactics were born.

Janet stayed at WATU until the end of the war, running simulations, teaching officers and refining tactics. When peace came the unit’s work was classified and its members bound to silence. She left the Navy, married, became a schoolteacher. For decades, her wartime role appeared nowhere but as a vague line in her employment history: “Operations, WRNS.”

Only in the 1970s, when wartime records began to be declassified, did the story of Western Approaches Tactical Unit and its Wrens begin to emerge. Scholars going through dusty files discovered reports written in Roberts’ careful hand, annotated game results, and references to innovations born on the linoleum sea. They also found a photograph from 1943: a line of young women in uniform standing in the pit, chalk dust on their shoes, one of them looking directly at the camera – third from the left, a slight figure with serious eyes. The caption lists them as “WATU staff”.

The caption does not say that two days after her brother was lost in the Atlantic, that young woman walked a Fleet admiral through a simulation of his own failure and forced him to admit that everything he had been teaching was wrong. It does not say that her equations shifted doctrine and saved convoys.

Yet her chalk lines did exactly that.

War histories tend to focus on ships and admirals, on machines and codes, on men whose names fill memorials. The story of Janet Okell reminds us that wars are also won by people whose battlefield is a floor and whose weapons are patterns and persistence – people willing to stand in front of tradition and say: this is killing us. We must change.

News

(CH1) How One Girl’s “SILLY” Chalk Trick Made German U-Boats Sink 3 Times Faster

At 6:43 on a cold Liverpool morning in March 1943, a nineteen-year-old woman stood in the middle of a painted…

(CH1) How One 14-Year-Old Girl’s “Crazy” Bicycle Trick Killed Nazi Officers

In the history of warfare, death usually wears a uniform. It arrives with the thunder of artillery, the scream of…

(CH1) How One US Woman’s “Shopping Trips” Saved 7,000 Allied Pilots from Nazi Prisons

March 2nd, 1943. Marseille. The coded telegram was short, cold, and devastating. “Pat has fallen.” Four hundred kilometers away, in…

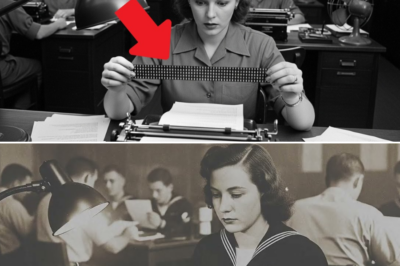

(CH1) How One American Woman’s Torn Typewriter Ribbon Saved 3,000 Lives and Sank 4 Japanese Carriers in 5 Hours

At 4:17 a.m. on May 25th, 1942, the ocean was still dark outside Honolulu, but inside the Fleet Radio Unit…

(CH1) How One Female Sniper’s “CRAZY” Trick Took Down 309 Germans in Just 11 Months

5:47 a.m. – August 8th, 1941. Belaya Tserkov, Ukraine. Twenty-four-year-old history student Lyudmila Pavlichenko crouched behind a pile of shattered…

(Ch1) How One Woman’s Bicycle Chain Silenced 50 German Tanks in a Single Morning — And No One Knew

At 5:42 a.m. on October 3rd, 1943, the gray morning light slid across Hall 7 of the Henschel & Sohn…

End of content

No more pages to load