Part 1 – The Contract

I used to think parents were supposed to help their kids until they could stand on their own, but I learned very early that mine believed the opposite. When I was twelve my mother handed me the permission slip for a field trip and told me to sign it myself because, in her words, I was “old enough to start taking care of my own stuff.” She added that now that I was twelve, I could also buy my own school lunch because “we’re not made of money, and you should understand the importance of hard work.” That was the day she stopped paying for my meals. It started small—school lunches and notebooks—and grew into everything else. When I asked for new pencils, she said, “Figure it out. Other kids your age have jobs.” I remember standing in the kitchen doorway holding a worn notebook, feeling both confused and embarrassed. My father was on the couch watching sports, the kind of premium package that cost more each month than my entire school supply list, but he said nothing. They had just bought a new sixty-inch TV, yet my ten-dollar box of pencils was apparently a luxury.

I started babysitting on weekends, walking dogs after school, doing anything to earn a few dollars. The money went straight to the essentials—food, notebooks, clothes that fit. I learned to make twenty-five dollars stretch for a week, measuring every dollar against hunger. Dad would laugh when I came home tired from a babysitting job and say, “Look at our little entrepreneur. Maybe you’ll finally learn why we can’t just give you everything you want.” I used to smile back because arguing was pointless. By thirteen they had stopped feeding me entirely while ordering takeout twice a week for themselves. I would come home from school to find boxes of Chinese food on the table and nothing left in the fridge. My mother would tell me to get a job at the grocery store and buy my own food “like an adult.” The smell of fried rice and chicken made my stomach cramp, so I learned to stay in my room until they were done eating.

The strange thing is, their neglect taught me discipline. I became better at managing money than they ever were. They bought gadgets and restaurant meals; I compared prices, searched for coupons, and built a small neighborhood business mowing lawns and pet-sitting. By fourteen I was making close to seven hundred dollars a month. It wasn’t wealth, but it meant freedom. My parents claimed my success was proof that their “tough love” worked. Dad liked to brag to his golf buddies that he’d “made me earn every dollar so I wouldn’t grow up spoiled.” He would say that while sipping forty-dollar wine at the country club, pretending that forcing a kid to buy her own school lunch was a form of parenting genius.

Then he lost his job, and everything changed—but not in the way you’d expect. Instead of humility, they doubled down on greed. They said they were “having financial difficulties” and asked if I could lend them money for groceries “just until your father finds something new.” I remember standing there, watching them panic over bills, realizing they had no savings despite earning good money for years. They’d spent everything on luxuries. Dad gestured toward my account and said, “You’ve got all that money sitting there. You could help out your family.” When I refused, he called me selfish. Mom said, “Family helps family,” and I reminded her that when I was twelve I had eaten peanut butter every night because they’d stopped buying food. She said that was different, that they had been “teaching me responsibility,” while this was “a real emergency.”

The requests became daily. When I said no, Dad accused me of being ungrateful. He liked to remind me that they could have “kicked me out years ago” but had “let me stay for free.” I told him that allowing your minor child to live in your home was the bare legal minimum, not a favor. Mom shouted at me not to be clever. For weeks it went on—pleading, guilt, then anger. Finally one evening they called me into the kitchen. They were both serious, sitting side by side as if rehearsed. “We’ve been talking,” Mom said, “and we think it’s time you start contributing to household expenses.” Dad nodded and slid a paper across the table. “You’re fourteen now, making good money. It’s only right you pay rent.”

I stared at the document. It looked official, with printed headers and signature lines. The number—six hundred dollars per month plus utilities—jumped off the page. My mind went blank. In a good month I made about seven hundred dollars. Utilities in summer added at least two hundred. That meant I’d have maybe a hundred left for food, clothing, school supplies, and gas for my mower. They were watching me like they expected me to sign immediately. Mom crossed her arms; Dad held out a pen. My voice shook when I said I needed time to think. Dad called me dramatic, but I walked to my room anyway and locked the door.

I opened my budget notebook, the one filled with neat columns of numbers, and did the math again. It didn’t work. Paying rent would drain the small savings I’d built—about fifteen hundred dollars I’d saved for emergencies and college applications. Within three months I’d be broke. My chest hurt as I flipped pages, trying to find a solution. None existed. That night I lay awake scrolling through my phone, searching for answers. I typed questions into forums: Can parents charge their minor child rent? The results varied, but most said the same thing: parents must provide food, shelter, clothing, and education until their child turns seventeen or eighteen. Some people online defended charging rent as “teaching responsibility,” but others called it neglect if the parents stopped supplying basics. I found a legal aid website that said parents are obligated to provide the essentials; charging rent is only acceptable if they still provide everything else. Mine didn’t. They hadn’t bought me food or clothes in years. I took screenshots of everything that looked important and saved them to a folder. Sometime after one in the morning I fell asleep with my phone still in my hand.

When my alarm went off, my eyes burned from staring at the tiny screen all night. At breakfast they were eating eggs and toast. I told them calmly that I wouldn’t sign anything until I talked to someone at school. Dad’s face flushed red. “You’re being disrespectful,” he said. “We have every right to charge rent.” Mom joined in, calling me a spoiled brat. My heart was pounding but I stayed steady. “I just want to make sure I understand everything before I sign a legal document,” I said. Dad slammed his coffee mug onto the counter, spilling coffee everywhere. I grabbed my backpack and left before he could step closer. He shouted something after me, but I didn’t look back.

The bike ride to school usually took ten minutes; that morning I did it in seven. I spent the first half of the day unable to focus, staring at my notebooks, wondering who I could trust to tell. By lunch I’d made up my mind. Mrs. Carter, the school counselor, had always seemed kind whenever I passed her in the hall. I told the office it was an emergency, and a few minutes later she appeared in the doorway and led me into her office. It was small but warm, with plants on the windowsill and motivational posters about kindness.

I told her everything. I told her about being twelve and having to buy my own food, about working since middle school, about the empty cupboards and the takeout containers in the trash, about the contract. She didn’t interrupt, just took notes and nodded. When I finished she looked genuinely alarmed. She asked if my parents had ever hit or threatened me. I said no, they just stopped taking care of me financially and now wanted to charge me rent. She tapped her pen thoughtfully. “I’m not a lawyer,” she said, “but this raises serious concerns. Parents are required to provide basic needs until at least seventeen. Charging rent while denying food and clothing could be considered neglect.” She opened a drawer and pulled out brochures for free legal aid. “Would you be comfortable if I made some calls to connect you with someone who can explain your rights?”

“Yes,” I said. My voice cracked. “Please.”

She stepped out of the room for a few minutes, talking quietly on the phone. When she came back she said she’d left a message with Legal Aid and they’d call within a day or two. Just telling her everything felt like removing a stone from my chest. For two years I had carried the weight alone, pretending it was normal. Having one adult believe me made me want to cry, but I held it in. Mrs. Carter also helped me apply for free school lunches right there in her office. She said there was nothing shameful about it. While we filled out the online form, she guided me through questions about income and family size, explaining how to note that my parents didn’t provide food money. She clicked submit and said approval usually came within days. When I left her office I felt lighter than I had in months. Someone knew. Someone cared.

The next afternoon, after school, she drove me downtown to meet Daniel Lawson, the lawyer from Legal Aid. He looked younger than I expected, maybe thirty, with glasses and a calm manner that immediately made me feel safe. His office was cluttered with boxes, but tidy in a way that said he liked order. He asked me to start from the beginning, so I did, recounting everything again. He wrote fast, asking careful questions. When I described the rent contract, he stopped writing. “Charging rent can cross into neglect if it prevents parents from meeting their obligations,” he said. “They’re legally required to support you until you’re of age. They can’t simply decide to stop.” He asked what I paid for myself. I listed everything: food, clothes, school supplies, toiletries. He made two columns on a yellow pad—provided and not provided. The second column was almost the whole page.

He asked about their income and spending. I told him about the cable sports package, the golf membership, the takeout meals, the wine, and how they’d only started struggling after Dad lost his job. He nodded, taking notes. Then he asked if I had proof. I showed him photos on my phone: the empty pantry, the trash full of restaurant containers, my notebook with earnings and expenses. His jaw tightened. “Keep all of this,” he said. “Documentation matters.” He leaned back in his chair. “I can send them a letter—formal, professional—outlining their legal responsibilities. It won’t threaten them, but it’ll make the law clear. Sometimes that’s enough to make parents reconsider.” I nodded quickly. “Please send it,” I said.

He printed a few pamphlets about children’s rights, handed them to me, and gave me his card. “Keep recording everything,” he said. “If they push harder, call me.” I walked out of the office feeling, for the first time, protected.

That night I was microwaving ramen when my parents came in. Dad crossed his arms. “Have you decided about the rent?” I turned to face them, heart pounding. “I talked to a lawyer,” I said. Mom’s face drained of color. “He said parents are required to provide basic needs until seventeen, and charging rent while refusing food could be neglect.” Dad’s jaw clenched. “You’re threatening us?” he shouted. “Making us look like bad parents?” Mom started crying, accusing me of being ungrateful after “everything we’ve done.” I stayed calm, repeating what Daniel told me—that I was happy to help around the house, but I wouldn’t sign anything that left me without food money. My hands trembled but my voice stayed even. When I finished, I walked to my room and locked the door behind me while they yelled about disrespect and ingratitude. I texted Mrs. Carter to say there’d been an argument but that I was safe. She wrote back immediately: I’m proud of you for standing up for yourself. Text me if anything changes.

The house was quiet for days afterward, a heavy, uneasy quiet that felt worse than shouting. My parents barely spoke to me except in clipped sentences. I knew they were waiting for the letter.

When I got home from school a week later, I could tell before I even opened the door that something was different. The television was off, which was rare, and the air in the kitchen was tight. Both of my parents sat at the table, papers spread in front of them. The envelope from Legal Aid lay opened like a wound in the middle of the mess. They didn’t look up when I came in. I walked past them, grabbed a glass of water, and went straight to my room. No one said a word. The silence was heavier than any argument we’d ever had.

For the next several days they treated me like I didn’t exist. Meals happened behind closed doors. The pantry stayed locked, but now I took pictures of it with time stamps. I photographed every grocery bag that came through the door, the empty cabinets they left for me, and the take-out containers that filled the trash. Every image went into a cloud folder labeled “home.” I didn’t know what might happen next, but Daniel had said to keep records, and that was something I could control.

Mrs. Carter started checking on me every day at lunch. She’d wave me into her office, give me a granola bar, and help me map out a schedule that fit school, work, and homework. My grades had started to slip; the exhaustion made it hard to focus. She wrote to my teachers explaining that I was dealing with family problems and asked for a little grace. For the first time, people around me seemed to see that I wasn’t lazy or distracted, just tired.

My neighbor Mrs. Parker noticed too. She’d see me hauling my mower and trimmer across the street and started asking gentle questions. I gave vague answers, but she understood more than I said. One afternoon she offered to let me keep all my tools in her garage. “They’ll stay dry, and you won’t have to lug them back and forth,” she said. Her tone was light, but her eyes weren’t. I moved everything over that same day, grateful to know my gear—and the little business I’d built—was safe.

Work helped. The grocery store manager, Ryan Brooks, noticed how careful I was at the register and told me they could use more hours covered in the evenings. I filled out the new schedule and signed the paperwork for a minor work-permit extension. The extra pay meant I could buy decent food and still save a little. At home, though, tension kept rising. My parents counted every item in the refrigerator and left notes about what was “off limits.” The notes stayed taped to shelves for weeks, a constant reminder that generosity was conditional.

I recorded everything. Each night before bed, I typed into a note on my phone what had been said, what food was left, what new rules appeared. The act of documenting became a shield; it turned chaos into evidence.

One Friday evening Dad confronted me the minute I came home from work. He had heard—from someone at church, he said—that I was getting free lunch at school. “You’re embarrassing us,” he snapped. “People think we can’t feed our own kid.” He stood in the doorway shouting until Mrs. Parker’s porch light flicked on across the street. She came out and stood there watching. Dad dropped his voice to a hiss, told me we’d “finish this later,” and slammed the door. My heart wouldn’t stop racing for an hour afterward.

Two days later I came home to find my mower and trimmer sitting in the yard, soaked from the morning rain. Dad said he’d moved them out of the garage to make space. The mower engine was ruined. I sat on the wet grass staring at it until Mrs. Parker walked over. She didn’t ask what happened. She just said, “Let’s get these inside,” and helped me drag everything to her garage. She handed me a towel and a glass of lemonade and told me that her guest room was always open if I ever needed a place to sleep. She said it like a casual comment, but her eyes made it a promise.

At work the following week Ryan Brooks pulled me aside. He’d heard about the confrontation at the store when my father showed up yelling. He said, “You did nothing wrong, and you’re safe here.” Then he offered me a permanent part-time position with a small raise and an employee discount on groceries. That simple kindness felt larger than any pay increase.

I tried to keep my head down, but home became a minefield. One afternoon I found Dad going through my desk drawers. When I asked what he was doing, he said he had every right to know what I did with “his roof over my head.” That night I moved my money into a prepaid debit account with online access only. My paychecks went directly there, safe from their curiosity.

A few days later word of the rent situation apparently spread through church circles. Dad came home furious, slamming cabinets and blaming everyone for gossip. He and Mom argued for hours about who had “blabbed.” I sat in my room listening to them turn on each other, realizing they cared more about appearances than truth.

Mrs. Carter called another meeting, this time including a district social worker. We sat around a conference table—me, my parents, Mrs. Carter, and the woman from the district office named Ms. Heller. My parents complained about how rude and ungrateful I’d become. Ms. Heller let them finish, then asked what support they provided me. The room went silent. When she pressed for specifics—food, clothing, school supplies—they stumbled. I explained calmly what I paid for myself. After nearly an hour we reached a temporary written agreement: no rent until I turned seventeen, but I would help more with household chores. Food and basic access were to be guaranteed. Ms. Heller printed three copies and made everyone sign. I photographed mine before leaving the room.

For a brief time the house was quiet. Dad sold his golf clubs to cover a credit-card bill. Mom found part-time work at a store in the mall and came home exhausted but at least contributing. We ate simple meals together—rice, beans, spaghetti. I could sit at the table without feeling like an intruder. One night while washing dishes she told me her own parents had been strict about money, how they’d made her account for every dime. It wasn’t an apology, but it explained something. I nodded and kept drying plates.

Dad eventually got a warehouse job on the night shift, loading trucks. The house became calmer with him gone at night. Mom even started attending free budgeting workshops through her work. She brought home spreadsheets and asked my opinion on them. It felt surreal to have her asking me for advice about saving money.

For a few months, things almost resembled normal. Then the cable bill appeared on the counter again—the sports package reinstated. The old habits were creeping back. The next morning Dad grumbled about rising costs and hinted that I should “start pitching in again.” I reminded him of the signed agreement, showed him the photo on my phone. His face reddened. That evening Mom approached me with a bright smile that didn’t reach her eyes and suggested a “chore credit system” where my work around the house would count toward “helping with bills.” I told her calmly that it was rent with extra steps and my answer was still no. She walked away muttering about how hard it was to raise difficult children.

That night I messaged Daniel about what had happened. He replied within minutes: Document everything. So I did—each meal, each comment, each attempt to twist the agreement. I logged what food was available, what nights they ordered pizza while I ate cereal, what money appeared and vanished. Turning my life into notes and photos was exhausting but gave me control.

Three days later Mrs. Carter showed me an email she planned to send to my parents. It was polite but firm: if they violated the mediation agreement, she would have to file a formal report with child-welfare services. I told her to send it. Watching her press “Send” felt like watching a lifeline shoot into the distance.

That Saturday, while I was stocking shelves at the grocery store, I looked up to see my father storming through the doors. His face was red, eyes searching. He spotted me and started shouting about how I was “turning people against the family.” Customers stopped to stare. My hands shook so badly I dropped a box of cereal. Ryan came out from the back room, stepped between us, and told my father he needed to leave immediately. Dad protested that he had every right to talk to his daughter. Ryan didn’t raise his voice, just said, “Leave now, or I call the police.” Something in his tone made Dad turn and march out, slamming the door so hard it rattled the glass.

I sat down on a step stool shaking. Jessica, the assistant manager, filled out an incident report and assured me they’d trespass him if he came back. For the first time, I believed I wasn’t alone in this.

That night I went to Mrs. Carter’s house. She listened quietly as I told her everything. When I finished, she said softly, “This crossed a line. I have to make a report.” The next morning a woman named Ms. Donovan called my phone. She introduced herself as a child-welfare caseworker and scheduled a home visit for Thursday. My stomach twisted with both relief and fear.

When I told my parents, they went into panic mode. Mom started scrubbing baseboards; Dad rehearsed lines about what great parents they were. I listened to them practice their version of the story and decided I’d just tell the truth.

On Thursday Ms. Donovan arrived exactly on time, a woman in her forties with calm eyes and a tablet in her hand. She asked general questions, then requested to speak to me alone in my room. I showed her my budget notebooks, my photos, the food logs. She took notes but didn’t look shocked. Then she toured the house, photographing the pantry and fridge herself. When we all sat down together afterward, she spoke evenly but firmly: parents are legally required to provide food, shelter, and clothing. Charging rent to a minor or restricting food can be considered neglect. She said she’d be following up regularly. My parents nodded stiffly, their faces a mix of shame and resentment.

When she left, Mom ripped the lock off the pantry door and threw it in the trash. Dad sat at the table scrolling through job listings, muttering about “government interference.” The next week they bought groceries and left them where I could reach them, sighing loudly each time. The rent contract vanished, unmentioned but not forgotten. I kept taking photos anyway.

Two weeks later Dad started his night-shift job at the warehouse, and for the first time in years the house was quiet. Mom seemed lighter without him around in the evenings. She even asked if I wanted anything specific from the store. I told her wheat bread and the cheap peanut butter I liked. She nodded and wrote it down.

It wasn’t happiness exactly, but it was peace, the first real peace I’d known since I was twelve. And even though I still slept with my phone and notebook beside the bed, ready to record whatever came next, I started to believe that maybe, just maybe, I could survive this house long enough to leave it for good.

Part 2 – The Letter

The morning that Daniel’s letter arrived, the sky hung low and gray over the neighborhood, the kind of light that makes every house look smaller and tired. By then I had learned to read the house like weather: the way my mother’s jaw set when she was angry, the way my father’s breathing grew loud and deliberate before a fight. When I stepped off my bike that day I could already feel it—the tight, humid pressure of something waiting to break. The Legal Aid envelope lay on the kitchen table, torn open, its corners bent from how hard my father must have gripped it. I set my backpack down quietly. Neither of them looked up. My mother’s hands were folded in her lap, her knuckles white; my father’s eyes were fixed on the papers. He didn’t yell, not yet. He just said, “You think you’re smarter than us now?” I didn’t answer. I went to my room, shut the door, and sat on the bed listening to the clock tick. The silence lasted days, a kind of punishment all its own.

The letter did what I couldn’t. It made everything real. Written in the clean, professional tone of someone who knew exactly how much authority a paragraph could hold, it explained that under state law, parents are legally obligated to provide their minor child with food, clothing, shelter, and education. It stated that charging rent or demanding payment for basic needs could constitute neglect and would be subject to further review if reported. The words were polite but final. When I read a scanned copy Daniel had emailed to me later, I saw how he’d chosen every line with care—neither threatening nor soft. Just the truth.

At home my parents stopped speaking to me except through notes. Grocery lists appeared on the fridge, written in my mother’s sharp handwriting: MILK, EGGS, BREAD, RICE. At the bottom she’d added, “Do not eat anything you didn’t buy.” When I took a picture of it for my folder, my hands were steady. Every evening I’d upload the new photos, tagging each one by date and time. Documentation had become my routine, as normal as brushing my teeth. It was the one thing that made the fear manageable.

At school Mrs. Carter noticed the way I jumped when a door slammed in the hallway. She kept her office door open for me during lunch, even when she had other students waiting. Sometimes we just sat there in silence while I ate the free meal she’d helped me apply for. The tray of spaghetti or sandwiches tasted better than anything I’d eaten in months, not because of the food but because I didn’t have to apologize for eating it. She’d ask gentle questions: How are things at home? Are you safe? And I’d answer honestly—safe enough, for now.

One afternoon she told me that Daniel wanted to check in. We met again at his office downtown, the same narrow room with file boxes stacked to the ceiling. He looked up from his notes and smiled. “You’ve done everything right,” he said. “Keep recording, keep your receipts, and if they try to change the agreement, call me immediately.” He handed me a copy of a second letter he’d drafted—this one outlining the mediation process if my parents refused to comply. He explained that he hadn’t sent it yet but wanted me to know it existed. The thought that there was another document waiting, like a backup parachute, made me breathe easier.

At home, things balanced on a thin edge. My parents’ anger had turned into something quieter: resentment that crept into every movement. They no longer locked the pantry, but they made sure I knew the groceries were a favor. My mother sighed loudly whenever she cooked, muttering about “ungrateful children.” My father worked nights at the warehouse, coming home before dawn with the smell of diesel on his clothes, too tired to fight but still angry enough to glare. On the nights he wasn’t working, he’d sit at the table scrolling through job listings, muttering about how people should “mind their own business.” I would sit in my room doing homework, headphones on but music off, listening for the sound of trouble.

Mrs. Carter and the social worker, Ms. Donovan, kept in regular contact. Ms. Donovan came back for her first follow-up visit two weeks after the letter arrived. She checked the pantry and refrigerator, asked about school, and reminded my parents that her visits would continue for several months. My mother smiled tightly and offered her coffee she didn’t really want to make. My father stayed quiet, his face blank. When Ms. Donovan left, my mother dropped the coffee cup into the sink so hard it cracked. I didn’t say anything. I just swept up the pieces after she went upstairs.

The weeks that followed were strangely calm. Without the constant threats, I could think again. I started keeping a real schedule: school, work, study, sleep. My grades improved. Mrs. Carter helped me sign up for a tutoring program, and for the first time in a long while I could imagine finishing high school with decent marks. Ryan Brooks at the grocery store kept me on steady hours, and between the job and my lawn work with Mrs. Parker’s neighbors, I had enough income to stop worrying about every dollar. I still lived like a survivalist, saving every cent, but it felt less like desperation and more like control.

Then, slowly, my parents began to unravel again. The first sign was the return of the sports package. I saw the cable bill on the counter with the new charge circled in red. They didn’t mention it, but the next evening my father complained about how expensive life was and how “everyone should pitch in.” I didn’t respond. I just took a photo of the bill for my records. The following week my mother started her chore-credit idea again, calling it “family cooperation.” She stood in the doorway to my room, smiling as if it were a generous offer. “You can earn credits for doing extra work around the house,” she said. “Each credit will go toward the household bills. That way you’re contributing.” I kept my voice calm. “That’s just rent with a different name,” I said. Her smile vanished. “You’re impossible,” she muttered, slamming the door.

That night I sent Daniel an email summarizing the conversation. He replied within half an hour: “Keep documenting. Don’t engage in arguments. If they threaten eviction or touch your earnings, let me know immediately.” I added his message to my folder. The folder had grown into a timeline of survival: photos, texts, notes, receipts, and now emails—an entire record of what it meant to live in a house where love was conditional.

My father’s temper found new outlets. One evening he accused me of embarrassing them at church because someone mentioned the free lunch program. He cornered me in the kitchen, voice rising until Mrs. Parker’s porch light came on again. She stood outside watching, silent but solid. Her presence cooled him down faster than words ever could. After he went inside, she caught my eye and gave a small nod, a signal that she was still there if I needed her.

The next weekend my mower finally came back from the repair shop. The mechanic had done what he could, but it would never run quite the same. Still, when I pushed it across Mrs. Parker’s lawn that Saturday, the familiar hum of the engine felt like freedom. She brought out lemonade and told me she’d added two new clients to my list—friends of hers who needed regular yard work. “They pay on time,” she said. “And I told them you’re reliable.” Her quiet confidence in me was worth more than the money.

Inside my own house, progress moved in uneven steps. My mother’s budgeting classes at work seemed to help. She started keeping receipts in an envelope instead of letting them pile up. She even asked me once how I tracked my expenses for my business. I showed her the simple spreadsheet I used. For a few minutes we talked like normal people, two workers comparing notes. It wasn’t forgiveness, but it was something close to peace.

One afternoon, after weeks of this fragile calm, Ms. Donovan returned for another home visit. She reviewed her notes, checked the kitchen, and smiled faintly. “I see improvement,” she said. “Keep it up.” My parents nodded politely. I could almost see the relief in their shoulders—proof that they were passing inspection. As soon as she left, my father muttered about government spies, but even that felt half-hearted. He was too tired from night shifts to sustain his anger.

I thought maybe we’d reached some kind of uneasy balance until the afternoon my mother knocked on my door holding a car repair estimate. “Your father’s brakes need work,” she said. “Could you lend us some money? Just until payday.” I didn’t hesitate. “If you’d like to borrow, we can make a written agreement—amount, repayment plan, and date.” I opened my laptop to draft it. Her face went pale. “Never mind,” she said, turning away. They never asked again.

Over time, the house changed shape. The big television disappeared; they sold it to pay down their credit card. The fancy wine was gone too, replaced by instant coffee. They still complained, but at least the bills got paid. Meals were basic but consistent. For the first time since I was twelve, I could come home and know there would be something to eat that didn’t require apology.

Two months later, an email arrived from the community college’s dual enrollment program. I’d been accepted with a full scholarship covering books and transportation. Starting in the fall, I’d spend my mornings taking college classes and afternoons finishing high school. I printed the letter and laid it on the kitchen table in front of them. My father glanced at it and said, “That’s good. Saves money later.” My mother nodded without looking up from her budget sheet. Their reactions stung, but I’d already learned not to expect pride from them. I folded the letter and slipped it into my backpack, saving that pride for myself.

The day after, we sat down to sign a new written agreement—this one drafted by Ms. Donovan and Mrs. Carter together. It listed everything clearly: no rent until I turned seventeen, specific chores, open access to food, and a line that said my income belonged solely to me. My mother read it twice, lips pressed tight, and then signed. My father followed with a grunt. I signed last and took a picture of all three signatures before handing the original to Mrs. Carter for her files.

That evening, we ate dinner together. The food was plain—baked chicken and rice—but nobody shouted. My father talked about a forklift breakdown at the warehouse. My mother complained about a rude customer. I told them about a history quiz I’d aced and a new lawn client. We weren’t laughing or sharing affection, but we were eating like a family, and that was something. After the dishes were done I went to my room, finished my homework, and realized I felt something I hadn’t felt in years: cautious hope.

I still kept my phone by the bed, still updated my folder, but the weight that had lived in my chest since I was twelve had started to lift. The letter, the evidence, the adults who stepped in—they hadn’t magically fixed my parents, but they had built a wall between their chaos and my future. For the first time, I could see a path that led somewhere other than survival.

Part 3 – The Caseworker

Ms. Donovan became a regular part of our lives, though my parents pretended she wasn’t. She arrived every month, exactly on time, her car pulling up in the driveway like a quiet announcement that someone was still watching. The first few visits were stiff and tense. My mother would greet her with forced cheer, offer coffee she didn’t actually want to serve, and then sit upright on the couch while Ms. Donovan scrolled through her tablet and asked calm, pointed questions. My father answered in short bursts, trying to sound cooperative but never hiding the resentment in his voice. The moment she left, he would mutter about “people who think they know better than parents.” Yet he never raised his voice again when she was gone. Her presence hung in the air long after her car disappeared down the street.

Over time, those visits changed the rhythm of the house. The pantry stayed unlocked, the fridge remained stocked, and bills got paid on time. My parents’ anger hardened into something quieter—disapproval without teeth. They knew that if they slipped, someone would notice. For me, that awareness became a kind of safety net. I no longer felt like a single bad argument could destroy everything I’d built. Instead, I had a pattern to follow: school, work, study, eat, sleep, repeat. Predictability replaced chaos, and that was enough.

Ms. Donovan never acted like a savior. She treated me like a person who needed information and structure, not pity. During one visit she asked how school was going. When I told her about the dual enrollment program, she smiled and said, “That’s impressive, Sarah. That kind of commitment will open doors for you.” No adult in my family had ever spoken about my future in those terms. My mother, standing at the sink, made a noncommittal noise but didn’t contradict her.

A few weeks later, Mrs. Carter called me into her office again. She said Ms. Donovan had updated her on the progress at home and that the district considered the case “stable but active.” That meant they were still monitoring, but as long as conditions stayed steady, the case wouldn’t escalate. I asked her what would happen if my parents reverted to old habits. Mrs. Carter’s tone stayed gentle but firm. “Then we start again. But you have proof now. You know how to get help.” Her faith in me felt stronger than my own.

By spring, my life had fallen into a pattern that felt almost normal. I woke at six, packed my backpack, went to school, worked my afternoon shifts, came home, ate dinner, and studied until midnight. My grades climbed back to where they’d been before everything fell apart. Ryan Brooks kept me on consistent hours at the store, and he started training me to handle the register alone. Sometimes when it was quiet, he’d show me how to read a pay stub or explain why taxes were withheld. He talked to me like a coworker, not a kid. That simple respect was worth more than any paycheck.

At home, my father’s new warehouse job kept him exhausted. He’d leave at nine each night and return at dawn, too tired to do more than mumble about aching shoulders before collapsing onto the couch. My mother worked daytime shifts at the mall and spent her evenings watching television on the small set they’d moved from their bedroom. The big one was gone for good. She complained about her feet, about rude customers, about missing her old life. But there was a different tone to it now—more weary than angry. Sometimes she’d even cook dinner before I got home, simple meals like rice and beans or spaghetti. The smell of food when I walked in the door was enough to make me forget, for a moment, how bad things had been.

One afternoon, I came home early from work and found her sitting at the kitchen table surrounded by papers. At first, I thought she was doing bills, but when I looked closer, I saw worksheets printed with colorful charts and questions like “List three financial goals for the next six months.” She looked up, embarrassed. “My job offers free finance classes during lunch breaks,” she said quickly, as if defending herself. “I figured it couldn’t hurt.” I didn’t know what to say. She kept talking, flipping through the pages. “They teach you how to track spending, plan savings, stuff like that.” She paused, then asked, “How do you keep track of your business money? You seem good at that.”

The question hit me in a strange way—half compliment, half confession. I pulled up the spreadsheet on my laptop and showed her how I logged my mowing income, expenses for gas and repairs, and the savings column I updated each week. She nodded slowly, taking notes. We didn’t talk about the past, but the silence between us felt less heavy than usual. It wasn’t forgiveness, but it was a start.

When Ms. Donovan visited again in early summer, she noticed the change immediately. The pantry was stocked, the bills were paid, and the mood was subdued but functional. After walking through the house, she sat down at the table and told us she was pleased with the progress. She looked at me and said, “You’re handling an adult’s workload at fourteen. You should be proud of that, but remember you still get to be a kid too.” My father gave a tight smile, pretending pride he didn’t feel. My mother nodded along, eyes down. After Ms. Donovan left, my parents went right back to their separate corners of the house, but I felt something new—relief. Every visit that ended without incident was proof that the system worked, that someone believed me.

The summer before sophomore year moved faster than I expected. I spent my mornings cutting lawns and my evenings at the grocery store. I started keeping half my earnings in a separate account under my business name—Carter Lawn & Pet Services. Mrs. Parker helped me set it up online, walking me through the process on her computer. She also offered to keep a spare key for my mower shed in her garage “just in case.” I knew what she meant. She didn’t have to say the words “in case you need to get out.”

By July, the house had quieted into a routine even my parents seemed resigned to. My father’s paychecks came every other week. My mother budgeted them carefully, grumbling but managing. The first time she handed me a grocery list and asked if I wanted anything added, I said, “Maybe wheat bread and peanut butter.” She actually wrote it down. When she came home from the store later, she held up the bag with a kind of awkward pride. “See? Got your peanut butter.” I thanked her, even though the brand was the cheapest on the shelf. Gratitude was easier than conflict.

The dual enrollment program sent me a packet with orientation dates and course options. Mrs. Carter helped me fill out transportation forms for the community college shuttle and arranged with my teachers to adjust my schedule once classes began. I spent nights researching textbooks and mapping out how to balance college work, high school credits, and my job. The structure made sense to me—it was predictable, measurable. I could plan around it, unlike my parents’ moods.

One evening in August, my mother knocked on my door and stood there holding a piece of paper. “Your father’s car needs brakes,” she said. “We don’t have the money until next paycheck. Can we borrow a little from you?” I looked at her, then opened my laptop and started typing a short loan agreement. When I finished, I turned the screen toward her. “If we write down the amount, the repayment date, and both sign it, that’ll keep everything clear.” Her mouth tightened. “That’s not necessary.” “It protects both of us,” I said. She stared at the screen, then shook her head. “Never mind. We’ll figure it out.” She left the room, closing the door harder than necessary. I saved the blank contract in a folder named “Family.”

A few days later, I noticed the large television was gone from the living room. My father mumbled something about selling it to pay off a card balance. The sports package had been canceled again. The living room looked smaller without it, but I didn’t miss the noise. For the first time in years, the house sounded like an ordinary home—footsteps, the hum of the refrigerator, the soft clatter of dishes.

By September, Ms. Donovan conducted what she called a progress review. We sat together at the kitchen table, going over her notes from previous visits. She asked each of us about money, food, and school. My parents pointed out the open pantry and the neat stack of bills marked “paid.” She nodded approvingly, then looked at me. “How are your college preparations?” I told her about the dual enrollment, the scholarship, the bus schedule. She smiled. “That’s remarkable, Sarah. I’ll be closing your case as stable but will continue check-ins every few months.” My mother exhaled audibly, like she’d been holding her breath for a year. My father managed a stiff thank-you.

After Ms. Donovan left, the tension in the house thinned. My father still muttered about outsiders, but he worked too many hours to stir trouble. My mother talked occasionally about saving for a smaller TV once their debts were clear. I focused on my classes and my job, counting the months until I could leave for good.

In October, Mrs. Carter called me into her office again, smiling as she handed me a printed email. “Congratulations,” she said. “You’ve been officially enrolled. Classes start next fall.” I read the letter twice, barely believing it. “You did this,” I said. She shook her head. “You did the work. I just made sure people saw it.”

When I walked home that afternoon, the air smelled of cut grass and autumn. My parents were in the kitchen arguing softly about something—probably money—but for once I didn’t stop to listen. I went to my room, opened my folder of records, and scrolled through the years of photos, notes, and messages. The locked pantry, the rent contract, the letter from Daniel, the visit from Ms. Donovan—all of it was there. Proof of how far I’d come.

Later that night, as I finished homework, my phone buzzed with a text from Mrs. Parker. Movie night Saturday? I’m making popcorn. I smiled and typed back, I’ll bring the lemonade. For the first time since I was twelve, I could picture a future that didn’t revolve around survival. It wasn’t freedom yet, but it was close.

Part 4 – Cautious Hope

By the time winter settled in that year, the air in the house had changed. The shouting had dulled into sighs, the anger into routine. My father still worked nights at the warehouse, leaving before I finished homework and returning when the sun came up, a ghost passing through our narrow hallway. My mother spent her afternoons behind a cash register at the mall, her smile fixed and thin, coming home with stories about customers who treated her the way she used to treat me. I didn’t say it, but part of me thought maybe she finally understood what it felt like to have people see through you. At dinner she’d rub her wrists and talk about how tired she was, how small the paychecks felt after taxes. I’d nod and pass her the salt, and we’d eat in a silence that wasn’t exactly comfortable but no longer dangerous.

The pantry stayed unlocked, stocked with bags of rice and boxes of pasta, peanut butter, cereal, the kind of ordinary groceries most people took for granted. I kept expecting to come home one day and find the lock back on, but it never returned. Instead my mother would sometimes ask me if I needed anything from the store before she left for work. Once she even bought me a new winter coat after noticing the old one had holes near the cuffs. She didn’t mention it when she handed me the bag, and I didn’t thank her out loud, but she must have seen the way I pressed the soft fabric between my fingers. That was enough.

Ms. Donovan’s visits became shorter, less formal. She’d arrive with her tablet, glance around, ask a few questions, and leave smiling. The word she used now was stabilized. She told me I’d done exceptionally well and that she was recommending the case be closed after one more visit in the spring. “You’ve built a life for yourself, Sarah,” she said during our last winter meeting. “That’s something no one can take away from you.” I didn’t know what to say, so I just nodded. My father grunted something like agreement, and my mother managed a polite thank-you. When Ms. Donovan’s car disappeared down the street, we all stood in the kitchen a moment longer than usual, as if waiting for the next line in a play we hadn’t rehearsed. Then my father said he needed to sleep before work and my mother started washing dishes, humming under her breath.

My own life moved forward. School no longer felt like an obstacle course. My grades climbed steadily, and I started spending free periods in the library filling out scholarship applications. Mrs. Carter checked each one for grammar before I sent it. She had become my anchor in the chaos of adolescence, always reminding me that the future wasn’t something that just happened—it was something you built piece by piece, like a wall that kept the dark out. “You’ve already done the hardest part,” she told me one day as she proofread my essay. “You’ve learned how to stand up for yourself. The rest is just logistics.”

At the grocery store Ryan Brooks promoted me to shift lead for weekend hours. It wasn’t official in title, but he trusted me to handle closing duties and train new hires. The extra pay made my budget easier, but more importantly, it made me feel capable. I could track my savings, pay for my own phone bill, and still keep a little aside for emergencies. Sometimes, when customers thanked me or asked for my help finding something, I’d feel an odd rush of pride. I was good at being reliable. That was something my parents had never managed.

Mrs. Parker’s house across the street became my refuge. On weekends when my parents’ tension thickened, she’d wave me over for coffee or help me with small home repairs. Her husband traveled often for work, so she said it was nice to have company, but I knew she was giving me a safe space to breathe. She never asked for gossip or details. Instead she gave me small lessons—how to unclog a mower blade, how to replace a spark plug, how to file simple taxes for self-employed work. “You’re going to need this someday,” she’d say, handing me a wrench. Every time I walked home from her place, I carried a little more knowledge and a little less fear.

When spring came, the world seemed brighter, though maybe that was just because I finally had time to notice it. I’d gotten used to the schedule: mornings at school, afternoons at work, evenings filled with homework and the quiet hum of my parents’ TV. My mother’s budgeting classes at her job had turned into a new habit; she’d sit at the table balancing expenses with a calculator, muttering to herself but not complaining as much. Sometimes she’d even show me the charts she’d made, color-coded with savings goals. “If we can keep this up,” she said one night, “maybe we’ll be out of debt by next year.” Her tone carried something like hope. I didn’t remind her that I’d been debt-free since I was thirteen. Some things were better left unsaid.

By April, my dual enrollment orientation letter arrived. I’d been assigned to take college composition and introduction to sociology, two classes that sounded intimidating but exciting. Mrs. Carter helped me arrange transportation, and Ryan agreed to adjust my work schedule so I could attend morning lectures. My parents barely reacted when I told them, just nodded and said, “That’s good.” But their indifference no longer crushed me. I was proud enough for all of us.

The day Ms. Donovan returned for her final visit, the air smelled like cut grass and rain. She walked through the house, checked the fridge, asked her routine questions, and then looked at me with a kind smile. “I’ll be closing your case this week,” she said. “If anything changes, you can always reach out, but I think you’re going to be just fine.” My father shook her hand with the weary politeness of someone eager to be done. My mother thanked her, voice quiet but sincere. When the door closed behind her, none of us spoke. It was over. The threat of social services, the inspections, the tension—it all dissolved into silence. I expected relief, but what I felt was strange emptiness, like walking out of a storm into still air. I had spent so long preparing for disaster that peace felt unnatural.

That night I went to Mrs. Parker’s house for dinner. She’d made roast chicken and mashed potatoes, and the warmth of her kitchen smelled like everything I’d missed for years. “To your freedom,” she said, raising a glass of lemonade. I laughed. “I don’t know if I’m free yet.” “You are,” she said. “You just don’t believe it.” I stayed until the stars came out, helping her wash dishes and talking about college plans. When I finally walked home, the streetlights cast long shadows on the sidewalk, and for the first time, I wasn’t afraid of going inside.

Summer came early that year. My lawn business thrived with new clients from Mrs. Parker’s network. I saved almost every dollar, knowing college expenses would come soon enough. My parents seemed to have settled into a truce with the world and with me. They didn’t ask about my earnings, and I didn’t ask about their finances. We shared the same space but lived separate lives. In the evenings, my father would sit on the porch with a beer, staring at the fading sunset, and sometimes he’d nod when I passed. It wasn’t affection, but it was acknowledgment, and that felt like progress. My mother even started talking about getting her GED. “I never finished,” she admitted one night. “I dropped out at seventeen. Maybe it’s time.” I told her she should. She smiled a little, almost shy.

One humid afternoon in July, I came home from work and found a letter on my bed. It was from the community college, confirming my class schedule and including a student ID card with my photo. For a few seconds I just stared at it, stunned. Then I laughed out loud, the sound echoing off the walls. My parents peeked into the room, curious. I showed them the letter. My father said, “That’s good,” and my mother said, “You’ll do great.” Simple words, but they meant something this time.

The day before classes started, I sat on the porch steps watching the sunset bleed into the sky. The air smelled like mowed grass and distant barbecue. I thought about everything that had happened—the rent contract, the letter from Daniel, the endless arguments, the visits, the quiet changes that followed. I thought about how many nights I’d fallen asleep scared of what tomorrow might bring. Now tomorrow didn’t scare me; it just waited, open and wide.

When September arrived, I walked into my first college classroom carrying a notebook I’d bought with my own money. The walls were plain, the desks scratched, the professor already writing on the board. I sat down near the back and took a deep breath. Around me were other students, older, younger, all of them strangers. For the first time in years, I didn’t feel lesser than anyone. I wasn’t the kid who had to buy her own pencils anymore. I was just another student trying to build a future.

That evening, when I got home, my mother was cooking dinner. The smell of chicken and garlic filled the house. My father sat at the table reading a job-training manual for a promotion he hoped to apply for. The television was off. The house was quiet except for the sound of sizzling oil and my mother humming a tune I hadn’t heard in years. She turned to me and asked how my first day went. I told her it went well. She nodded and said, “I’m proud of you.” The words were soft, almost hesitant, but they hit me like a wave. I managed to say thank you before excusing myself to my room. Behind the closed door, I sat on the bed and let myself cry—not from sadness, but from the sudden realization that I had made it through.

That night, as I wrote in my notebook, I realized I no longer needed to document every moment out of fear. I kept the folder of evidence, but it was part of the past now, not the present. The locks were gone, the shouting had faded, and even if the peace was fragile, it was real. I thought about what Mrs. Carter had said: that the hardest part was already behind me. She was right. The hardest part had been believing that I deserved more than survival.

When I turned out the light, the house was quiet except for the sound of my parents talking softly in the kitchen. For the first time in a long while, their voices didn’t make me flinch. I lay in bed and listened, feeling the weight of cautious hope settle over me like a blanket. It wasn’t forgiveness and it wasn’t forgetfulness, but it was enough.

And that’s where I decided my story could finally rest—not in the anger or the struggle, but in the stillness that comes when you know you’ve changed the ending. I was fourteen when my parents tried to make me pay rent. Now, as I prepared for college, I was no longer the child who had to fight for pencils or meals. I was someone who had learned how to protect herself, how to build boundaries and keep them. That kind of strength doesn’t fade. It stays, quiet and steady, like the hum of a mower or the whisper of a counselor’s voice saying, “You’re going to be just fine.”

END.

News

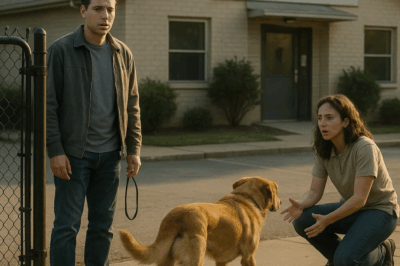

(CH1) A MAN ADOPTS A DOG, BUT THE NEXT DAY SHE RUNS BACK TO THE SHELTER – FOR A REASON NO ONE EXPECTED

A New Way Home For thirty-eight years, John and Sally Harper’s mornings began the same way: with sunlight leaking through…

(CH1) A homeless Black woman collapsed by the roadside, her two-year-old twin children crying in despair

The early morning haze still lingered over San Francisco’s Mission District when Alicia Moore collapsed to her knees beside the…

(CH1) “I’ll pay you back when I’m grown up,” the homeless girl pleaded with the millionaire, asking for a small box of milk for her baby brother who was crying from hunger — his response stunned everyone around.

“I’ll pay you back when I’m grown up,” the homeless girl pleaded with the millionaire, asking for a small box…

(CH1) “Grandma, i’m so hungry. he locked me in my room and mom won’t wake up.” my seven-year-old grandson whispered from a number i didn’t know.

My name is Judith Morrison. I’m seventy-two years old, and this is my story. The phone rang at 8:30 on a…

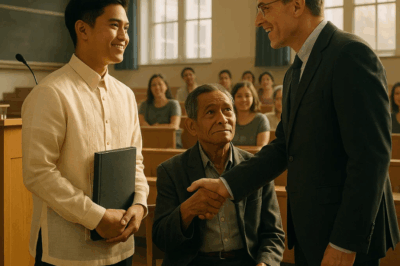

(CH1) My stepfather was a construction worker for 25 years and raised me to get my PhD.

Part I – Beginnings in Dust and Rice Fields I was born into an incomplete family, the kind where silence…

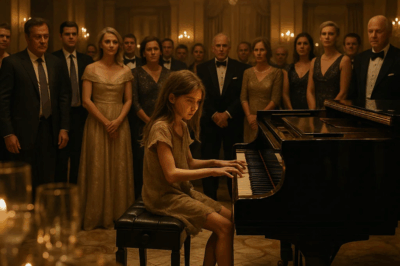

(CH1) “Can I Play for a Plate of Food?” The Moment a Starving 12-Year-Old Girl Sat at the Piano — and Silenced a Room Full of Millionaires…

The hotel ballroom shimmered with golden light, polished marble floors, and chandeliers like frozen stars. It was a charity gala…

End of content

No more pages to load