I used to think the worst thing I’d ever hear from my family was my mother’s sigh when I called to say the doctors had confirmed I couldn’t carry a child. “This is what happens,” she said, “when you push your body too far with that dancing.”

I’d trained for ballet since I could stand on my toes, the one part of our picture-perfect Boston family that didn’t fit: a daughter who wanted to live on stage, not in a boardroom. Then a torn knee at nineteen reduced that future to a scar and a limp when it rained. Three surgeries, a recovery that ran longer than anyone promised, and a note from my mother tucked into a stack of college brochures: Now you can go to school like a normal person.

I moved to Chicago instead. I built a modest design business out of a laptop and long nights and a stubborn streak that wouldn’t die. When a social worker put a wide-eyed seven-month-old girl into my arms, I stopped being the failure my family had rehearsed in their heads and became something I had always wanted: a mother. Not through blood. Through choice.

Madison was—and is—a light the world is lucky to have. She drew before she talked, asked questions in series thick as rain, insisted on purple somewhere in her outfit every day. I told her early and often that she was adopted, that there are many ways to create a family and ours was beautiful. When she asked about Boston—about my parents and my little brother, Eric—I kept answers soft. “They live far away,” I said. “Sometimes people take time to understand.”

The invitation to Eric’s wedding arrived in a heavy cream envelope with gold embossing. Eric had been engaged for five years to a woman who seemed to live in glossy magazine pages; they were finally setting a date in June at a resort near Cape Cod. Part of me wanted to recycle it unopened. The last time we were all in a room, at my father’s sixtieth, had been a weekend of thin smiles and my mother’s sharp comments about my “cramped little apartment” and Madison’s “energy.” But when Madison’s eyes lit up—“A wedding? Do I get to wear a pretty dress?”—I heard myself say yes.

My mother called that night to make sure we were attending. “Eric specifically asked me to make sure you’re bringing Madison,” she said, in the tone she saves for obligations dressed as invitations. I wanted to believe it. I wanted my daughter to be seen.

Two months later we walked into the resort’s polished lobby and found my mother standing like a portrait. She gave me an air kiss, looked at Madison like she was an errand to be checked off, and announced dinner at six. At the table, an aunt kept asking loudly whose child Madison was. “She’s Caitlyn’s adopted daughter,” my mother said each time, drawing the word out as if it were a warning label. Natalie’s mother leaned across her salmon and said, “It was so generous of you to take on someone else’s child,” the way you’d compliment a stranger for adopting a greyhound. Madison sat up straighter. I placed my hand on her shoulder.

On the beach afterward, we kicked off our shoes and watched waves carry other people’s worries away. “Why does Grandma always say I’m adopted when she introduces me?” Madison asked.

“Some people think family is only about blood,” I said. “But they’re wrong.”

The morning of the wedding, I ordered room-service pancakes to avoid breakfast with judgments. Madison twirled in her lavender dress, checked her reflection, and asked, “Do I look like I belong in the family now?”

“You’ve always belonged in our family,” I said, kneeling so we were eye to eye. “No dress changes that.”

The ceremony was beautiful in the way money can buy: flowers arched like a cathedral, ocean standing politely behind vows. Madison squeezed my hand during the kiss. My chest unclenched enough to wonder if this might be easier than I feared.

Then we followed the crowd into the reception hall. There was a table with white place cards dancing in neat alphabetical rows. Madison ran ahead, excited to find her name.

She found a card. Her hand stilled. She read it aloud in a small voice: “Fake daughter.”

The room’s hum dipped. Heads turned. Somewhere a fork hit a plate.

Eric appeared at my side, Natalie hovering a step behind him, her smile straining. I handed him the card. He flushed. “It’s probably… a joke,” he said. “Someone’s stupid idea.”

“A joke?” I repeated.

He looked away. “Everyone knows she’s not—”

“Not what?” I asked quietly, acutely aware of Madison’s eyes on his face and of the watching circle of relatives.

He swallowed. “She’s not really family.”

Madison’s breath hitched. The sound cut me where nothing else ever had.

Natalie hustled forward with damage control. “My cousins can be… immature. We’ll find the right card.”

I found Madison curled in a bathroom stall, crying silently against her knees. “Why don’t they like me?” she whispered when I gathered her up. “What did I do wrong?”

“Absolutely nothing,” I said, with more certainty than I felt. “Some people have small hearts. That’s not your fault.”

“Do you want to leave?” I asked. “We can go now.”

She wiped her face and surprised me. “I want to stay. You say standing tall shows you’re stronger.”

We fixed her mascara. We straightened her sash. Then we went back in.

At the escort table, I picked up a blank card, took a pen, and wrote real daughter in clear letters. I placed it where the insult had been. There were gasps from somewhere behind me; I didn’t look. I found the microphone instead.

“For those who don’t know me,” I said, voice steady though my hands shook, “I’m Caitlyn, the groom’s sister. I wasn’t scheduled to speak. But I realized there’s something more important than sticking to a script.”

I met my daughter’s eyes in the crowd and held them.

“Eight years ago, I adopted Madison. I didn’t give birth to her. I chose her—and she chose me, every day since. Today someone wrote ‘fake daughter’ where her name should be. Someone else suggested that was, in a way, true. So let me be clear: family isn’t defined by DNA. It’s defined by love, by showing up, by making space for each other without conditions.”

I raised a glass. “To Eric and Natalie. And also to real family—the kind made by commitment and care. If you can’t see that in a child as extraordinary as Madison, you’re missing something worth seeing.”

Some people stood. Some didn’t. Some looked at their laps, ashamed. My mother’s mouth thinned. Natalie’s eyes were bright with something like understanding. Eric looked like a boy who’d broken a window and finally heard the glass.

Madison hugged me so hard I felt her ribs. “I love you,” she whispered.

“Always.”

An hour later, we left. I booked a room in a yellow bed-and-breakfast down the road where a woman with flour on her apron brought Madison cookies and asked her questions until the tightness went out of her shoulders. My phone vibrated itself across the porch railing—calls from my mother and father, from numbers I didn’t recognize, a text from Natalie that said I’m sorry. Can we talk? and thirteen missed calls from my brother. When I finally answered him, his voice was hoarse. “I’m sorry,” he said. “I said the worst thing out of the easiest habit. Can I apologize to her in person tomorrow?”

We met at a cafe for pancakes. He crouched to Madison’s eye level and said what he needed to say without excuses. “Why did you say it if you didn’t mean it?” she asked. “Sometimes grown-ups try to please the wrong people,” he told her. “It’s not right. I won’t do it again.” He meant it. I could tell. We flew home that afternoon.

The fallout lasted weeks. My mother left voicemails alternating between icy lectures and tremulous pleas for family unity—as long as unity looked like silence. My father sent nothing but a rigid birthday card for Madison that said, Wishing You the Best with no signature. Eric began calling every Sunday to ask Madison about school and to ask me, without saying them exactly, if I would let him be a brother again. Natalie emailed to say she was pregnant and wanted Madison as a cousin, not a prop. “Every child deserves to be claimed,” she wrote. “We didn’t do that for her. We will now.”

Boundaries became a practice, not a rant. I consulted a family attorney who put what I already knew into legal words. I found a child therapist who helped Madison turn nights of nightmares into days of drawing stars with steady hands. We replaced Sunday dinners with Sunday choices: museums, recipes that made flour float in the kitchen air, blanket forts, a rotation of our favorite parks. When my mother asked to meet for coffee without Natalie, she told me about the girl she had been—a girl who loved to draw and learned to stop when her own mother told her art didn’t put food on a table. It explained a lot. It didn’t undo anything. But it let me see where some of her sharpness came from.

That winter, Eric showed up at our door with a box that smelled like butter and vanilla and a framed photo from his wife’s grandmother’s attic. Someone had written around the border in careful script: Family comes in many forms. You are part of this story now and always. He said my parents wanted to come for Christmas. “Real gifts, not gift cards,” he added wryly. “They’re reading books about adoption. They’re trying.”

“Trying” is a word I have learned to respect more than I used to. They came. My mother knelt, for the first time I can remember, to listen to Madison describe her science project. My father handed her a leather album embossed Our Real Granddaughter, half full of old photographs I’d never seen and half blank pages waiting for a life he finally wanted to witness.

It wasn’t a movie. It wasn’t instant. It wasn’t perfect. It was a beginning.

On a Tuesday night six months after the wedding, Madison and I strung purple lights around our apartment windows while the radio played carols softly. She held up a cardboard star she’d covered in glitter. “On this side,” she said, very serious, “only purple ornaments. Artistic balance.”

I laughed and handed her the step stool. “You’re the curator.”

She hung the star, stood back, and nodded. “Mom?”

“Mm?”

“Do you think Grandma and Grandpa will ever love me like you do?”

“No one will ever love you exactly like I do,” I said, because we don’t lie to each other. “But I think they’re beginning to understand what they’re missing. And I think they’re going to spend a long time making up for it.”

She thought about that. “I’m glad we went,” she said. “If we didn’t go, nothing would have changed.”

She was right. I had gone hoping my family would embrace my daughter. Instead, I stood up in a room full of people who preferred their definitions neat and got messy for the right reasons. I drew a line in calligraphy they could not erase: a mother and a child are a family by love, not by labels. I left a party and something else behind. I came home lighter than I had been in years.

Sometimes the bravest thing you can do for someone you love is speak their name into a microphone in a hostile room. Sometimes it’s walking out. Sometimes it’s calling a cab to a yellow B&B and ordering pancakes. It is almost always choosing to love your people loudly enough that even the ones who don’t deserve a seat at your table can hear it.

News

(Ch1) Racist Cop Pulls Over Black Girl in Luxurious Car And Arrests Her. Then This happen…

The cruiser’s lights washed the afternoon in red and blue, a pulse against storefront glass and the glossy black of…

I Reserved A $5,100 Venue For My Son’S Birthday. When We Arrived, The Banner Read “Happy 8Th, Harry!

I started saving on a Tuesday. Six months before my son’s eighth birthday, I opened a new account at the…

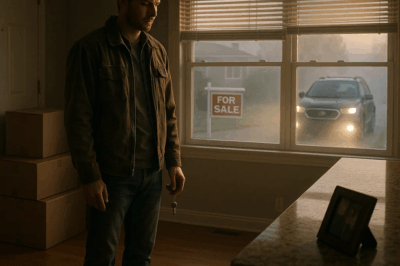

(Ch1) Fiancée Asked for a ‘Break’ to Revisit Her Cheating Ex. I Sold My House, Moved Across the Country..

I didn’t notice the exact moment my fiancé began to drift. That’s the thing about erosion—you only recognize it when…

(Ch1) Rich Young Master Spends Money To Force Black Maid To Crawl Like A Dog Just For Fun – Her Reaction Shocks Everyone…

Rich Young Master Spends Money To Force Black Maid To Crawl Like A Dog Just For Fun – Her Reaction…

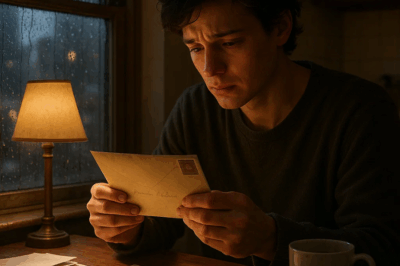

(CH1) After Three Years Of Silence, I Received A Letter From My Dad. But When I Looked Closer…

I was on my second cup of coffee and my third read-through of a tax evasion case when the doorbell…

I Didn’T Get Invitation To My Brother’S Wedding, So I Went On A Trip & Sorry Dear This Event Is Fo

I was halfway through a mindless Instagram scroll when the algorithm ambushed me with a photo of my older brother…

End of content

No more pages to load