May 8th, 1945

Outside Darmstadt, Germany

The field had once been a pasture.

You could tell by the way the ground rolled gently, the faint lines where fences had been, the scraps of trampled clover trying to grow back through the mud. Now it was just a square of flattened earth under a thin, pale sky.

Thirty-eight women sat in rows on that ground.

They wore what was left of Luftwaffe grey—Luftnachrichtenhelferinnen, signal corps auxiliaries. The great “female reserve” of the Reich. Once they’d looked sharp in crisp uniforms with polished buttons and piping. Now the cloth hung loose on thin shoulders, cuffs frayed to threads, insignia roughly ripped off in the last, hurried days.

They had been told to remove the eagles and swastikas before surrender. It didn’t matter. Everyone knew who they were.

Their ages ran from eighteen to twenty-nine, though starvation and fear made them all look older and younger at once. One had streaks of grey in her hair at twenty-four. Another, twenty-seven, was missing three teeth from a winter infection no doctor had time or medicine to treat.

They were hungry.

Not the skipping-lunch hungry they’d once known. Not even the winter 1943 hungry when rations shrank and women took in their skirts. This was the kind of hunger you learned to stop naming. The kind that lived behind every breath, behind every thought. Their last official ration had been three days earlier: one ladle of watery potato soup that had tasted mostly of salt and despair, and a slice of bread so packed with sawdust and ground beet that it scratched going down.

Now they sat on their helmets or on their coats, knees pulled up, hands resting on grey wool. Around them, American rifles made a loose ring. The rifles were carried casually, muzzles pointed at the ground, but everybody knew they could be raised in a heartbeat.

The women waited.

They had heard the stories. Everybody had. The Americans were better than the Russians, yes, but they were still victorious soldiers. Men with death in their hands and revenge in their blood. They would shout. They would take. They would do the things whispered about in cellars when the air raids were over and the lights still off.

So the women waited in silence. Because that was what German women had been taught to do when the worst came—be quiet. Endure.

At the far edge of the field, a young American lieutenant watched them and tried to swallow the knot in his throat.

Daniel O’Connell was twenty-four. Back home he was just Danny, the second son of a San Antonio mechanic and a schoolteacher. Out here, he was Lieutenant O’Connell, Company B, 347th Infantry, 87th Division. He’d landed in Europe in January, fought his way through snow and hedgerows, through villages whose names blurred together. In the last month alone he’d seen Buchenwald and a dozen smaller horrors that would follow him into sleep for the rest of his life.

He wasn’t sure what he’d expected when they told him a group of German “signal girls” had surrendered to his battalion.

Not this.

From where he stood, they didn’t look like villains of any propaganda poster. They looked like the girls who sang in the choir at St. Mary’s on Sunday. They looked like the tired waitresses at the diner on Broadway who kept the coffee coming when the factory shifts changed. They looked like his kid sister Mae would, in a few years, if she’d spent too long without food.

Their faces were hollow, cheekbones sharp under dirt. Their hair was cut practical and short under caps that now lay in their laps. Some had bruises. A few had the dull yellow tint to their eyes that said jaundice. All had the same expression: a tight, watchful fear that never quite cracked.

One girl in the front row—dark hair, eyes too big for her gaunt face—kept her gaze nailed to the ground. Another, with a sharp jaw and faint freckles under the grime, stared straight ahead as if she could force herself invisible.

“Lieutenant?” Sergeant Harris came up beside him. The Texan’s voice carried that lazy drawl even when he was reporting casualties. “What d’you want us to do with ’em?”

“Orders say process and move to the temporary cage,” Danny said automatically. He’d been fighting long enough that the words came without thought. “They’ll be transferred to Corps in the morning.”

Harris nodded. “We got the MPs comin’ with trucks.” He paused, eyeing the women. “They—uh—look bad, sir.”

“Yeah,” Danny said.

They looked worse than bad. They looked like the Hungarian Jews he’d seen at the camp outside Weimar—only cleaner and with uniforms. His brain kept flicking back and forth between those images, between piles of shoes and straight-backed Luftwaffe girls, trying to connect them in a way reality hadn’t yet.

A gust of wind blew across the field, carrying with it a smell Danny knew better than his own name.

Coffee. Real coffee.

And behind it, faint but unmistakable, came another scent: frying spam, powdered eggs, biscuit dough hitting hot metal.

He closed his eyes briefly. The division kitchen trucks still came up every day. Big green monsters with hinged sides that opened out like stages, revealing stoves and shelves and the big aluminum pots that churned out calories. To him, the smell now meant “piss warm, muddy coffee and spam again.” To these women, it was something else entirely.

He opened his eyes and looked back at them.

The dark-haired girl in front, the one with the too-big eyes, had turned her head almost imperceptibly toward the scent. Her nostrils flared. The freckled woman swallowed visibly.

They knew the smell. They just didn’t believe it had anything to do with them.

“Christ,” Danny muttered.

“Sir?” Harris asked.

Danny blew out a breath. He was tired to his bones. He wanted a shower and a clean cot and twelve hours without someone needing him to decide whether they lived or died.

But he also remembered yesterday—just yesterday—handing a Hershey bar to a French kid in a ruined village and watching the boy dissolve into tears at the first bite. He remembered the way the boy’s mother had looked at him, not as a conqueror, not as an enemy, but as someone who’d handed her child a tomorrow she hadn’t had to beg for.

He thought about that, and about these girls, and about how the war was finally, officially over as of midnight. How somebody had to start behaving like it.

“Bring the kitchen trucks up,” he said.

Harris blinked. “Sir?”

“You heard me, Sarge. Get the field kitchens over here. Tell ’em this is priority. We’ve got mouths to feed.”

Harris scratched his head under his helmet. “They’re Germans, sir.”

“They’re hungry,” Danny said. “And they’re human. That’s enough.”

The sergeant studied him for a long second, then nodding. “Yes, sir.” He raised a hand and whistled sharply. “Carter! Go flag the kitchens. Tell ’em the LT wants hot chow on the double. And if they complain, tell ’em to take it up with me.”

Carter, a skinny kid from Ohio, grinned. “Wanna throw eggs at Kraut girls now, Sarge?”

Harris shot him a look. “Wanna do KP for a month, Carter?”

Carter’s grin faded. “No, Sarge.”

“Then you tell ’em what I said. Move.”

As the runner loped off, Danny felt a peculiar mixture of dread and rightness settling in his gut. He had no idea how Division would feel about him feeding prisoners from combat rations. He also didn’t much care.

The war was over.

He could start doing the right thing a few hours early.

At first, the rumble of engines made the women flinch.

They’d had enough of the sound of trucks. Trucks meant movement, meant unknown destinations, meant marches that ended in places you didn’t get to leave.

Erika Müller, nineteen, from Hamburg, squeezed her hands into fists in her lap and told herself, the way she had since January, not to cry where people could see.

Her stomach cramped at the smell that came with the trucks.

She knew spam now. They all did. The Americans loved it. She could pick out the odors of fat and salt and a sweetness that came from the meat being… not quite meat. She smelled eggs too, and coffee, and something else that tugged so hard at her chest she nearly choked.

Butter.

Real butter.

The last time she’d tasted it was in late ’42, when her father had managed to trade for a small pat at the docks where he worked. They’d taken turns with the knife, each family member spreading the thinnest layer on their ration bread, tongue savoring every trace.

The memory hurt as much as her hunger.

“Don’t look,” Ruth Becker whispered beside her. Ruth was twenty-one and from Munich, though the war had mostly burned Munich out of her. “If they think we are like dogs, they will treat us like dogs.”

Erika nodded, but her eyes kept sliding to the side.

The American kitchen trucks rolled up with a squeal and a hiss. Panels clanged open. Men in aprons hopped down, shouting to each other as they unlatched the big pots and started the stoves. The smell multiplied with heat, filling the flat air with promises.

Erika kept her face as blank as she could.

She had been told, like all of them, what the enemy was. Crude, loud, greedy. They’d be full of hate now that the war was over. They’d make them beg for crumbs or worse. They’d make them perform for food. Their hands. Their dignity.

The tall lieutenant walked toward them with a clipboard.

He had straw-colored hair that curled a little at the ends. His uniform looked somehow both rumpled and neatly kept. His boots were filmed with dust. The patch on his sleeve showed a gold clover leaf on a blue background. She did not yet know this was the 87th Division; she would learn that later.

He spoke through a German interpreter in a too-clean uniform, a man with an accent from somewhere near Bremen.

“We need to know,” the lieutenant said, “if any of you are badly hurt or sick.”

For a moment, no one moved. Then Elsa Käne slowly raised one hand. Her two boys had been in her mind since February; she hadn’t bothered thinking of what she herself needed. Now, the fever haze made it hard to ignore. Her leg still bore a wound that hurt whenever she put weight on it.

Another woman lifted her hand, coughing. Another showed the pale scar of a recent shrapnel graze.

The lieutenant walked along the row and made marks on his clipboard. His face did not change when he saw the yellowed bandages, the swollen joints. He asked short questions: How long? Does it bleed? Can you walk?

He made notes.

And then he did something nobody there expected.

He handed his clipboard to Sergeant Harris and walked over to the kitchen line.

He took a mess tin from the stack, scooped a ladle of scrambled eggs into it. The eggs were yellow and steaming, flecked with pepper. He added a thick slice of spam, glistening where the hot fat had just kissed it in the pan. Two biscuits followed, fluffy and split, each with a generous smear of butter that melted and ran down the sides. Finally, he used a clean spoon to add a dollop of peach jam—so bright a color it made some of the women squint.

Then he turned and walked back to the first row.

“Here,” he said in slow, careful German. “Essen, bitte.” Eat, please.

He held the tin out to Erika.

She stared.

Her hands, when they lifted, were shaking so badly that the metal rattled when it touched her fingers. She clamped down hard to try to stop it. The warmth seeped through to her skin, startling after so much cold.

It could be a trick, some corner of her whispered.

But the eggs steamed in the cool air. The biscuits smelled of flour and salt and fat. The jam shivered when she moved.

She raised the fork. One bite. Just one.

The eggs touched her tongue.

She closed her eyes because she could not not close them. The texture was soft, almost unreal after months of dry, stale bread. The taste was magnificent.

When she swallowed, the food went all the way down without scratching, without getting stuck halfway as the coarse bread often did. Her stomach clenched in shock, then opened greedily.

Her eyes filled. Tears ran over the sharp bones of her cheeks, cutting clean lines through the grime.

“This,” she whispered in German, in disbelief more than gratitude, “is the best food I ever had.”

Lieutenant O’Connell didn’t understand the words, but he understood the tone. He offered her a small, crooked smile and moved on.

He did the same for Ruth Becker, for Elsa Käne, for each woman in that front row, then handed his tin to the next man in the kitchen line and grabbed another.

Within ten minutes, there was a second line—American soldiers with tins, passing them down the rows like an assembly line, each filled with the same obscene portion of luxury.

Some women ate slowly, taking minuscule bites, as if afraid that eating too fast would make someone snatch it away. Others ate so quickly they choked, tears and egg and spam all muddled together. A nurse from Leipzig—Helene, who had once worked in a hospital that smelled of starch and carbolic and now smelled of memory—pouring coffee into tin cups, watched them with eyes that shone.

She had brewed ersatz coffee for three years—a bitter, foul brew of burnt barley and ground acorns. Now she watched German women drink the real thing, dark and strong, with canned milk and two spoonfuls of sugar.

Elsa sipped once and her lips trembled.

“Donerwetter,” she breathed, not quite a curse, not quite a prayer.

Some of them couldn’t eat right away. They held their tins against their chests, feeling the heat sink into bones that had been cold for too long. Rocking slightly, because something in them needed motion to match the emotions surfacing far too fast.

Private Ruth Becker, who had stood straighter than anyone when the officer gave orders, sat down hard after one bite and covered her face. She had not tasted butter since 1942. She had not known it could still taste like this. She ate and cried at the same time, choking, laughing, making soft, strangled sounds.

Across the field, American GIs watched.

Most had seen enough carnage not to be easily moved. Most had lost friends whose names still sat raw on their tongues. Many had seen German troops fight with ferocity and cruelty. Some had the images of concentration camps burned into their minds.

But they also had mothers. Sisters. Girls back home who worked in factories and diners and libraries.

One GI—Private Tom Jenkins from Kansas—reached into his pocket, pulled out the Hershey bar he’d been saving, and passed it down the row to the girl nearest him. She frowned at the silver wrapper like it was a strange piece of machinery. When she tasted it, her eyes went wide.

Another soldier lit a Lucky Strike and passed the pack along. Soon, smoke drifted up in lazy spirals, mixing with the smell of eggs and spam and the faint scent of cheap American soap.

The interpreter sat with them too, translating snippets of conversation.

“Where are you from?” Danny asked.

“Hamburg,” Erika said, voice small.

“Munich,” Ruth whispered.

“Outside Kassel,” Elsa said. “Two boys. I haven’t seen them in two years.”

“Do you know where your families are?” he asked gently.

Most shook their heads.

“Wohnung zerstört,” Helene said. Apartment destroyed.

“Vater vermisst.” Father missing.

The words piled up like rubble. Each a small collapse.

Danny nodded, not pretending to have answers.

“I’m from Texas,” he offered in return. “San Antonio. Hotter than this. We have pecan trees. My little sister is learning to drive a combine.” He mimed steering a big wheel, eyes wide in mock horror. “She will kill us all.”

The interpreter struggled with “combine,” then settled on “riesiger Traktor”—giant tractor. The women actually laughed. It came out high and strange, like a sound they hadn’t used in a long time. But it was laughter.

Night found them still there.

The field darkened, the air cooling. The kitchen fires burned low. Risking reprimand, Danny made another decision.

They would not march in the dark to some anonymous wire cage. Not tonight.

“Blankets,” he told Harris. “Real ones. There’s an empty barn on that farm over there. We’ll post guards. They can sleep under a roof for once.”

“Division’s gonna love this, LT,” Harris muttered. But there was no heat in it. He turned and did as ordered.

The women stood shakily, clutching their tins, and shuffled toward the barn. They were given wool blankets that smelled of mothballs and laundry and a country they’d only ever seen in news reels as a land of gangsters and jazz. They spread straw on the floor and lay down in close rows, the murmur of German and English and the soft crackle of the barn’s old beams blending into something like peace.

Before they went, each woman received a small paper bag.

Inside were two Hershey bars, a tin of spam, a pack of Lucky Strikes, and a folded note written in careful, school-book German.

“Sie taten Ihre Pflicht. Wir taten unsere. Der Krieg ist vorbei. Willkommen zurück in der Menschheit. –87th Inf Div, USA”

You did your duty. We did ours. The war is over. Welcome back to the human race.

Some read it once and tucked it away. Some read it over and over until the paper went soft at the creases. A few kissed it, embarrassed, when they thought nobody was looking.

Years later, many would still have that note in a drawer or in the pressed pages of a Bible. The paper would yellow. The ink would fade. But the words would remain.

In 1949, in a small Lutheran church in a Wisconsin town that smelled of timber and snow and cows, Erika Müller stood in a plain white dress and said “I do” to an American farmer named Frank Higgins.

She had come over as a “war bride,” part of the trickle of German women who followed soldiers home. Not Lieutenant O’Connell – he would always be in her memory as the man who gave her the first eggs – but another GI from the 87th who had written her letters from his parents’ farm, describing trees and tractors and the way the sky looked in autumn.

Above the dresser in their house, framed and protected from the grease of years, hung a small, slightly crumpled piece of paper: the note from the field outside Darmstadt.

Every Christmas, Erika baked biscuits with too much butter and scrambled eggs and thick slices of ham. Her children preferred pancakes. She made those too. But sometime before noon, she always sat them down with a plate that looked suspiciously like an American field breakfast and told them the story:

Of when she thought the enemy would hurt her and instead handed her a tin of eggs and said, “Essen, bitte.”

Her grandchildren would roll their eyes after the fourth or fifth telling. But they’d remember. When they smelled bacon, they’d think of their grandmother’s thin hands and the way they’d trembled lifting a mess tin.

In Bremen, Ruth Becker opened a bakery.

It was a tiny place, wedged between a butcher and a tobacco shop on a street that still bore scars from the war. She named it “Danke 1945.”

Her first attempt at biscuits was a disaster. The dough came out hard, the bottoms burnt. But she had a cookbook now, sent by a former American soldier who’d come through the city years back and recognized her in the market.

She tried again. This time the biscuits rose. They browned just so. When she split one and spread real butter on it, she sat at the little table in the back, took one bite, and found herself crying into her apron.

Customers came. Some wanted rye bread like their mothers had made. Some wanted fancy tortes and pastries. A surprising number wanted the “Amibrotschen” – the Americano rolls – especially the kids. They were fluffy and warm and slightly sweet, and Ruth never forgot that the recipe had come from a field kitchen and a note that said “Welcome back to the human race.”

Elsa Käne found her sons.

Two years after the barn night, she tracked them down in a displaced persons camp, thin and wary and taller than she remembered. They stared at her cane, at the scars puckering her leg.

“Was ist mit deinem Bein passiert, Modi?” one asked. What happened to your leg, Mom?

She brought them home to a small flat in a rebuilt Stuttgart. The first real meal she cooked for them wasn’t sauerkraut or potato soup. It was scrambled eggs and spam and biscuits.

They ate three helpings each, eyes bright, mouths slick with fat. Halfway through the second pan, she leaned over the stove and wept, wooden spoon clutched in her fist.

The boys looked at one another, unsure.

“Schmeckt es nicht?” one ventured. Does it not taste good?

“Doch,” she said, laughing through tears. “It tastes like… like when someone who should hate you decides not to.”

They didn’t understand all of it then. Years later, when they read her note—still folded in her jewelry box, alongside the wedding ring she no longer wore—they would.

In 1978, Darmstadt held a small ceremony in a park that had once been a field.

There was a plaque now: “Hier bekamen am 8. Mai 1945 38 deutsche Kriegsgefangene Frauen von amerikanischen Soldaten die erste anständige Mahlzeit seit Monaten. Möge Menschlichkeit nie vergessen werden.” Here, on May 8, 1945, 38 German female prisoners of war received their first decent meal in months from American soldiers. May humanity never be forgotten.

Twenty-one of the original thirty-eight women came back.

They were in their fifties and sixties now. Their hair was grey or dyed or thinning. They walked with canes, pushed prams with grandchildren, linked arms with husbands—some German, some American.

They stood in a loose semicircle while the mayor gave a short speech, while a pastor said a prayer. Then one by one, each woman stepped forward and read the note she still had, or at least the words she still remembered.

“You were doing your duty. We were doing ours. The war is over. Welcome to the human race again.”

Some voices shook. Some were clear. Some broke halfway through.

Afterward, they sat under trees that had grown tall in the intervening decades and passed around baskets of biscuits and jars of jam, thick slices of sausage and wedges of cheese. They poured coffee from thermoses. The smell rose up, strangely unchanged.

An American delegation had come too, a few surviving veterans of the 87th, their children, their grandchildren.

One man, with a name tag that read “Sean O’Connell – son of Lt. Daniel O’Connell,” stood with them, listening. Later, Erika would pull him aside and tell him about his father’s drawl and the way he’d said “Essen, bitte” with such careful seriousness.

“My father wasn’t perfect,” Sean said. “But I’m glad to know that, at least once, he got it exactly right.”

Sometimes peace begins with signatures on thick paper in gilded rooms.

Sometimes it begins in quiet villages when men put rifles down and pick up hammers.

And sometimes it begins on a dusty field where thirty-eight women sit waiting for the worst—and instead find warm food pressed into their hands by boys whose uniforms should mark them as enemies.

Years later, if you had asked those women when they first knew the war was really over—not in Berlin or Reims, not in cables and proclamations but in their own bodies—they would not have said “When we heard about the surrender.”

They would have said, “When the Americans fed us. When the smell of coffee and eggs and butter came across the field, and we realized we were being treated not like enemies, not like cattle, not like abstract guilt, but like people. When someone looked at us, in our torn uniforms and our fear, and said with his hands and his actions, Welcome back. You belong to the human race again.”

For the rest of their lives, whenever they tasted real butter or smelled coffee on a cold morning, the memory would surface.

The empty field. The tense silence. The unexpected clatter of pots. The young lieutenant’s awkward German.

“Essen, bitte,” that voice would say, across countries and decades. “Eat, please. You’re home now.”

Not home as in Hamburg or Munich or Kassel. Not even home as in Texas or Wisconsin. Home as in something larger, shakier, but infinitely more important.

Home as in: the part of the world where we choose mercy over vengeance.

The uniforms would fade, the flags would change. But the taste of that morning—the eggs, the biscuits, the spam and jam and coffee—would remain.

Because some moments are bigger than victory and defeat.

Some moments are simply the place where someone decides that hunger has no uniform, and that the right way to end a war is not just with silence, but with a plate held out and the words:

“Eat, please. You’re human. So am I.”

The end.

News

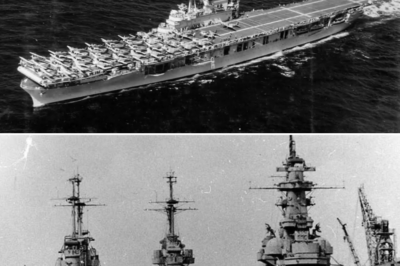

(CH1) Captured German Officers See a US Aircraft Carrier for the First Time

The first time they heard about the American carriers, most of the officers in the Kriegsmarine laughed. It was early…

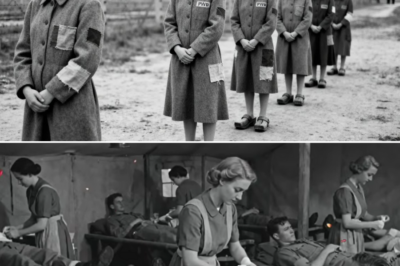

(CH1) German POW Nurses Said: “You Treat Us Well, How Can We Help?” — “Heal Our Wounded”, Said The General

When the trucks stopped at Camp Rucker, the Alabama sky looked wrong. It was too big, too blue, too indifferent…

(CH1) Captured German Nurses Were Shocked With American Medical Abundance

The first thing that hit her was the smell. Not blood, not gangrene, not the sour stench of bodies crammed…

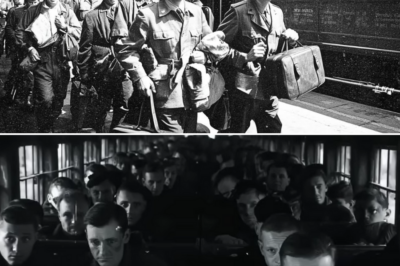

(Ch1) When German POWs Reached America They Saw The Most Unexpected Thing

The first thing that hit him was the smell. Not coal smoke or cordite or the sharp bite of disinfectant…

(Ch1) Female German POWs Didn’t Expect New Shoes—and Socks—in America

The order came in English first, then in rough, accented German. “You’ll remove your shoes now.” The voice was flat,…

(Ch1) He Taught His Grandson to Hate Americans — Then an American Saved the Boy’s Life

January 1946, the war was over, but the ground still killed. In a ruined German city, American combat engineer Paul…

End of content

No more pages to load