The house had a way of making sound feel small. Footsteps clipped across marble and disappeared into high ceilings; voices ricocheted off glass and faded into the echo. It was the kind of place that made magazines: a modernist cube in a quiet London street, all clean lines and river-blue reflections. The kind of place where bouquets arrived twice a week and the fridge had two drawers labeled charcuterie and herbs. The kind of place that looked like a life.

For Ethan, it was just big.

He was five—well, almost six if you asked him and he had a need to be precise—and small in that way children are small when ceilings are thirty feet high. He loved toy cars, and Lego bricks, and the bear with the matted ear that didn’t look appropriate on the leather sofa but lived there anyway. He loved picture books he could bend his head into and find a world where the houses were always exactly his size.

He did not quite know what to do with a house that stayed cold unless someone turned it warm.

His mother’s voice came through the house each morning around ten, contained in rectangles: iPad on the kitchen counter, phone wedged between shoulder and cheek, television tuned to a 24-hour business channel. In those rectangles, she was always in motion—boarding something, closing something, appearing somewhere. In those rectangles, she was time zones and screens: New York today, LA tomorrow, a meeting she couldn’t reschedule, a breakfast she would make up to him next week when she got back.

“Mommy loves you, darling. Be a good boy, okay?” she would say, and sometimes the words were so fast that the sentiment didn’t know where to settle before the signal went.

Victoria Lawrence had been on magazine covers by thirty. At thirty-five, there were profiles that used expressions like empire and visionary. Now, at forty-two, she could not step into a hotel lobby in any city that mattered without a concierge whispering her name as if they had a secret. She owned a portfolio of companies that made everything from software to luxury candles; there was a private equity fund that bore her hypothetical great-granddaughter’s initials. She had grown her gift for seeing patterns in markets into a discipline, then into a life. That life had bought the house and the art and the precise knives in the drawer.

It had not figured out how to buy minutes.

The woman who had, in a quieter way, learned how to pull minutes out of strange days was named Grace.

She was forty-two, too, though she looked younger when she laughed, which was often. She was from Birmingham, and the cadences of it stayed in her vowels like sunlight through a window you decide never to cover. She wore her hair in braids that Ethan loved to pat when he was very little—“like rope! like spaghetti!”—until he learned not to touch without asking. She had worked as a paediatric nursing assistant when she was younger, then as a nanny in three families she still ate Sunday roast with when her schedule allowed. She had never been on television. She knew exactly how to rub a tiny back so the cough loosened, exactly how long to let a tantrum breathe before a hug, exactly which vegetables could be made agreeable with a roast and which needed to be hidden in a sauce. She knew how to do the right voices for bedtime and how to move through a too-large house as if warmth were a thing you could hold and pass from one room to the next.

Officially, she was on the payroll. Practically, she was the house’s heartbeat.

She arrived at seven each morning, a blue scarf looped twice around her neck, and let herself in with the code. She started coffee, not for herself—she preferred tea—but because the kitchen smelled safer with coffee in it. She warmed the milk Ethan would pour over cereal if he were in a cereal mood—eggs if he wasn’t—and checked the school list for World Book Day or PE kit or bring in a piece of fruit for sharing. She moved through the house like a song you didn’t know you liked until you realized you were humming it.

“Up you get, champ,” she’d say, pulling back his duvet and letting a square of light widen on the floor. “Here’s the plan: we need teeth, socks, and the blue jumper because you’re growing like mushrooms and the grey one thinks it’s a crop top. Agreed?”

“Agreed,” Ethan would say, even on mornings he needed the joke to coax the grump out of his mouth.

He would eat at the island, swinging his feet, and tell Grace fierce, small opinions about playground politics. She would tuck his homework in the right side of his backpack and his bear into the left and they’d see whether the driver had a new joke, and then off they would go—to school, to life, to a day that was an ordinary day because Grace was the kind of person you build ordinary around.

In the afternoons, there were snacks and Lego treaties and sometimes an after-school club where Ethan made a dinosaur out of papier-mâché that seemed to have three heads until you realized he’d included the tails. In the evenings, there were baths that made the bathroom smell like pears and exactly two stories and the kind of prayers Grace had muttered since she was nine and did not mind if Ethan learned, too: thank you for today, help me sleep, help me be kind tomorrow.

Sometimes, without warning, the phone in the kitchen would ring, and it would be Victoria, voice bright with apology or bright with adrenaline—the same brightness, differently applied. “Tell me everything,” she’d say, and mean it for sixty seconds. “Mommy loves you,” she’d say at the end, and mean that completely, in a part of her the meetings didn’t reach.

Sometimes, she arranged to be home on a Sunday, and there would be scones and a story about a meeting that had involved a table made of a single slab of petrified wood, and she would kiss Ethan’s hair twice as if to make it count. Sometimes, she did not make it, and the scones were saved for Monday and then for Tuesday and then quietly broken into crumbs for birds.

“Adults have jobs,” Ethan told himself the way children tell themselves things so they do not hurt. “Mommy’s job is bigger.”

He never said out loud that big things cast shadows. He didn’t have the words for that yet. He had the sensation that the day of his life was often bright and often fun and often held, and also that the person he wanted to show the best drawings to was a FaceTime square.

Two weeks into a New York-LA-New York loop, Victoria flew home on a Sunday because one of the companies had made her whole week useless with success—a deal closed early without the drama she had put herself in charge of managing. The plane landed at dawn; she stepped into the house at noon, silk suit falling off her like a costume she could not quite shrug off.

“Ethan!” she called, moving through rooms she did not spend enough time in to know what sound lived where. She was on a call—earning or spending exactly one human life’s worth of money, depending on your politics—and she raised a finger when the small figure in trainers zoomed around the corner.

“Just a moment, darling. Mommy’s on a call.”

His face changed. That was the only way to describe it. His eyes remained the same eyes; they learned a way to arrange themselves so the mouth did not betray them. He stopped mid-run and put his hands in the pockets Grace had made for him in the jacket that had inexplicably come without any. He looked at the floor he’d been about to skid across.

Grace, who had learned not to take personally a life that asked her to be necessary, watched from the doorway and felt something twist she was sure God did not intend to untwist all the way.

Victoria ended the call. She bent, arms open, smile wide. “Come here, sweetheart. Give Mommy a hug.”

He moved toward her because he had been taught to be polite and because he loved her and because you can have two feelings at once. He took two steps. He felt himself hesitate. He turned, without planning to. He ran past his mother’s knees and flung himself at Grace’s middle.

He buried his face in fabric and said, clear and fierce into the blue of her dress, “You’re the real mummy.”

The sentence landed on marble like a dropped glass.

Victoria straightened. For a second, her hand hovered in the air as if it could reverse a motion she now understood. She let it fall slowly to her side. The smile slid off her face and left something thinner.

Grace did not do theater. Her eyes widened and then she shut them and kissed the top of Ethan’s head and said softly, “No, love. Your mummy is right there. She loves you very much.”

“She’s never here,” Ethan said, because children do not know they are writing an indictment when they report the facts of their experience. “You’re always here.”

Victoria sat on a sofa that had always seemed like a monument to her ability to afford comfortable things. She looked like a woman measuring the cost of something she had not budgeted for. She put both hands on her knees and tilted her face into them and let two tears go where they wanted.

The house heard. Houses do.

Three days later, on a flight back to JFK, she opened her laptop and did not see line items. She saw Grace four feet away catching her son like it was a job and a vocation and a thing you did because you said you would. She saw herself telling an assistant she could not possibly shift the board meeting because it was the board meeting that made all the other meetings possible. She saw her own childhood in a different set of windows—a townhouse in Knightsbridge, a French tutor who smelled like peppermints, parents whose calendars looked like war maps. She had sworn at sixteen she would be nothing like them.

“Daniel,” she said into her phone, because he was the one person she could choose to say vulnerable things to, and had not in too long. “Do you think Ethan even knows me?”

There was a silence that made the inside of the plane louder. Her husband had spent the last six months doing deals two islands of an ocean away, and they had gotten good at the teamwork of absence. “He knows your name,” Daniel said eventually. “He knows you love him. And he knows Grace is the one who chooses him all day.”

She hung up and set the phone face down. When it buzzed, she did not flip it over.

That night, London time, she went into Ethan’s room and stood in the doorway and watched something she had not watched in a very long time: her son asleep, breath even, cheek smooshed against a bear who had been pushed into service since he was a thumb. Grace sat with one hand on his hair, humming the hum everyone who stood in that doorway had learned was the safest mode to be in this room.

“He doesn’t sleep well if he doesn’t hear someone,” Grace said in a whisper, not looking up. “Maybe he does now, though. He’s very brave.”

Victoria nodded and did not trust words. The hum looked simple until you remembered what made it possible.

She woke early the next morning, because old habits hide behind coffee and then insist on themselves. She went into the kitchen with a jaw that had not yet found something to clench about. She ignored the phone on the counter. She opened the fridge like a person in a sitcom and had to text Grace to ask where the eggs were.

“Top right, darling,” Grace texted back with a heart emoji, because there are some things you can be tender about even with your boss.

Victoria cracked the eggs into a pan the way the internet taught you to do: low heat, patience. A smell spread like permission. Ethan came running and yelled into the morning, “Grace, it smells good!”

He turned the corner and then made the face again. “Mommy?”

“Yes,” Victoria said. “I thought we could try my eggs. We can have Grace’s later if they’re… you know…” She flapped a hand. “Bad.”

“They can be like dinosaurs,” Ethan said, which is a quality rating someone has to be six to understand. He climbed onto a chair and leaned his arms on the island. “Can I stir?”

“Do we stir eggs?” Victoria asked, and he laughed at her in a way that made her understand she had just become a different kind of person: someone who could be laughed at by their child and not feel undermined, only less alone.

It was a small moment. All the things that almost undo people also arrived that day: two urgent emails, a call from New York about an acquisition, a Slack message from an assistant with the degree of panic she had trained into her teams because she had believed panic was a kind of excellence. She looked at the phone. She looked at the eggs. She turned the phone over and tucked it under a dish towel as if it were a bird she did not want to watch her.

Grace watched from the doorway, one part proud, one part terrified on Victoria’s behalf. She had seen mothers fight big wars like this with themselves and sometimes lose without looking like it; she had learned that the only thing she could do in those moments was make sure there were clean forks.

That afternoon, because life is efficient when it needs to be and cruel when it is efficient, Ethan got a fever that rose like a power bill. He cried for Grace even though he loved Victoria because your body asks for the hand that learned what temperature you knew when you were one.

Grace looked at Victoria. Victoria nodded. “Go home,” she said. “It’s Saturday. Your sister’s birthday.”

Grace hesitated—I’m paid to be here—and Victoria said, “Please. I am asking you for help. Help me be the person he needs.”

She sat beside the bed and lay a cool cloth across a small forehead. She counted breaths. She sang a song she didn’t remember she knew until the second verse arrived and pulled the third behind it. She watched a digital number inch down. She slept sitting up and woke when he moved and did not pick up her phone when it buzzed in the kitchen.

At dawn, he turned toward her with a damp head and said, “You stayed.”

“I did,” she said, and the sentence weighed more than her last three acquisition memos combined.

Grace brought tea in quietly and put it on the dresser and went home to shower and cry because love and relief live in the same organ.

Change looked like paperwork.

Victoria called her general counsel on Monday and said, “I am reprioritizing twelve months. If that costs us volume, we will innovate here instead.” She called her chief of staff and said, “Set hard boundaries. Block 4:30–7:30 as if dinner were the board.” She called her private equity partners and said, “I expect you not to be surprised if I say no.”

She called Grace to the study and said, “Will you sit?”

Grace sat and folded her hands and felt a kind of dread known only to women whose jobs exist inside homes they do not own. “Is everything… do I need to—”

“No,” Victoria said quickly. “No, Lord, no. You do not ever need to wonder if you are about to be asked to pack.” She swallowed. She looked at her hands the way people look at their feet when they are about to do something too hard for eye contact. “I owe you an apology. I left you with… everything. I left you to do the thing I was supposed to do. You did it with more grace than grant you. And if I had snapped at you for being what you had to be while I was practicing a different kind of ambition, you would have had to swallow it. I am sorry. It is not going to happen again without being named.”

Grace studied her face, which was not the face of a client about to absolve herself with a takeout dinner and a raise. “Thank you,” she said carefully. “That’s a lot to hear, and good.”

“There’s more,” Victoria said. “I’ve always paid above market. It turns out market is sometimes a whisper from people who don’t think your work is skilled. We’re building a proper contract. Overtime protected. Health care through my company because of course. Two weeks paid leave you schedule for yourself and not just the days I’m gone. A seat at holidays. Not because you’re paid. Because you’re family. But we will write this down, so you never have to wonder whether my gratitude is… performative.”

Grace laughed with her eyes. “You’re bossing me around in a way I can live with.”

“And boundaries,” Victoria added, glancing up to check if she were pushing her luck. “I am going to try to do the bedtime. If you hear me failing, you are not allowed to rescue me unless someone is bleeding.”

“I will hide in the kitchen,” Grace said solemnly. “I will watch the monitor and drink tea and say prayers for patience.”

They built a schedule around school and life and work. Victoria did drop-offs on Tuesdays and Thursdays. She learned the name of the assistant head and how to tie shoelaces when the bow refused logic. She learned to let Ethan struggle with Lego instructions without fixing them with money. She learned to leave the phone on the dresser and learned how to carry it around like a loaded weapon safely when she had to, which is to say: with awareness.

There were relapses. The phone would buzz during bath time with an email about a crisis someone had decided would become a crisis at 6:17 p.m. Her fingers would itch the way alcohol itches in someone trying not to order a third drink. She would breathe and press the red button on the call and watch the ripple of water in a tub and count the silly purple cups they used as fountains because they were for tea tonight. She failed twice. She said the word sorry twice in a way that did not make it Ethan’s job to reassure her or Grace’s job to pretend it had not happened. The third time, she left the phone in the kitchen.

She moved a CFO to a division she didn’t care about for telling her she couldn’t do her job competently if she weren’t at every dinner. She prepped her COO in how to say “We’ll get back to you Monday” as if it were the most professional sentence in English.

Daniel flew home for a month. They sat on the roof one night after the city had turned into a map of its own. They did not talk about budgets or a friend’s divorce or whose parents were coming in May and what that would mean. They talked about the child sleeping one floor down and the two people he belonged to and the third who had stood in as if it were a calling.

“I resented you,” Daniel said in the dark in the way people can only admit true things when they don’t risk seeing the effect immediately. “Because you had the story that looked like the surface and I had the story that looked like a net, and people said yours mattered more.”

Victoria didn’t defend. “I resented you,” she said. “Because you never seemed to feel guilty and I did everywhere.”

They touched hands. They forgave each other. They learned to be less alone in the work of their particular home.

On a bright Saturday, they went to the park without Grace. The grass was damp with London, and the playground was chaos. Ethan climbed to the top of the frame like an astronaut. He froze there, ran a hand along a rope, adjusted his small bravery, and slid. He hit the dirt with a whoop.

“Did you see?” he shouted to the person he wanted to chain to an anchor.

“I saw,” Victoria said, and clapped like the start of a business day. “I saw all of it.”

Later, at the ice-cream van, she bought one for Grace, too, because she understood the math: you did not break a habit of absence by replacing one person with another; you did it by making the circle wide enough to hold everyone.

The first time Mommy reached toward her without its old sting, it happened in the smallest possible way. Ethan was building a puzzle and one piece would not find its angle. He turned it three ways and huffed. He looked up. “Mom—” He corrected himself without thinking. “Mommy, can you help?”

She crouched and that joint popped because she was forty-two, and she did not feel old enough to have a joint that popped. She did not comment. She and a small person turned a piece of illustrated cardboard the way you do when you are looking for where in the picture of the world it belongs. When it slid home, she found herself obscenely close to tears.

Grace saw from the doorway and returned to the kitchen to wash a dish that did not need washing.

There were setbacks: one day the phone again, one day a board member cursing at her in a way she had not been cursed at, one day Ethan refusing to put on his trainers because he was six and one day he did not want to and it had nothing to do with a wound she feared would never close now that she had looked at it. She learned to see which part of the resistance was about her and which part was about the shoe. She learned to say “We don’t talk to each other like that” to herself and perhaps, just once, dramatically, to a board member.

In late autumn, Victoria’s company launched a product she had shepherded for two years. The queue at the flagship store wrapped around a block. She watched from behind a glass door as a thousand people clapped for a thing her mind had helped make. She smiled, shook hands, took photos. She checked the time. She handed the microphone to her COO and said, “Thank you,” into it, and the you meant the crowd and the woman who held the clipboards and the babysitter she had still texted because you cannot make a habit of presence into a weapon either.

She was home in time to put a glow-in-the-dark sticker on a solar system that needed Saturn to look like it had its hat on.

Grace stayed on through it all. She did not lose herself in being needed: she took the leave she was owed and went to Birmingham and there were photos of her sister blowing out candles and her nieces with smudged hands. She gave Ethan what she had always given him—steadying—but with more room for someone else to be called upon first.

On a Sunday two months after the sentence that had changed the house fell out of a child’s mouth uninvited, Ethan turned to Victoria in the back seat on the way home from church and said, “Mommy, I love you and I love Grace. You and Grace are my mummy.”

Victoria swallowed fast so the liquid in her mouth did not undo her ability to speak. “We both love you more than anything,” she said. “Isn’t that good math? Two mummies, one Ethan who is the best thing either of us will ever get to look after.”

He thought about it like a philosopher and said, “It is very good maths.”

Years moved like river water: fast when you looked away, slow when you needed them to. Ethan learned to ride a bike in the driveway. He chose a bedtime story by words-per-page metrics no one had taught him. He lined up his toy cars with an OCD neatness that worried no one because everybody organized something to make the world make sense. He grew a little space between front teeth that made him look more like Daniel and less like the curled-lip baby in the house’s first-professional-portrait.

He was older the day a boy in a blue jumper said, on the playground, “My mum isn’t like that; at least she’s there.” The sentence landed with a thud he recognized in his own memory. He went home and did not mention it for three nights.

On the fourth evening, in the windowed slice between bath and bed, he said, voice casual in the way grownups forget children can use casually like camouflage, “Freddie said at school that you weren’t there before and that is because you love your work more.”

Grace was drying his hair. She and Victoria exchanged a look—in it, solidarity and fear and gratitude for each other. Victoria took the towel and sat on the floor.

“Freddie is telling a story about how he thinks things work,” she said. “Sometimes stories are true and sometimes they’re easy because they are short. Here is the long one. When you were born, I had a job that was like a fire. I believed if I didn’t feed it all the time, it would go out. I let it be the biggest thing because I thought I was protecting us. The fire was not bad; it paid for the house and the Lego and about… a thousand pairs of socks. But I let it make me forget something.”

“What?”

“That you are the only person who will be five exactly once,” she said. “I missed things. Grace made sure you still had someone for them. And then she told me the truth without using mean words, because the truth was heavy enough to carry by itself. I am sorry. And I am here.”

He nodded slow, the way you nod when somebody hands you a sentence that needs time. He said, “Okay. But if you get a trophy at work, can I take it to show-and-tell?”

“Yes,” she said. “And if you get a sticker from school, can I put it next to my computer so I remember what I’m building all this for?”

They did not tell him everything. There are pieces of a story you file into memory when the person with the small toothbrush can bear them. They told him enough that he would not learn it from teenagers trying out cruelty as a sport.

The photos on the mantel changed. There was one with Grace’s arm around Victoria’s arm around Ethan’s shoulders on a beach no one remembered the name of two years later because names were not what mattered. There was one of Victoria in jeans, hair wild, grinning like a different kind of article. There was one of Daniel and Ethan at an Arsenal match holding a scarf and looking like the embodiment of brand loyalty, which is to say: silly and earnest at once.

On the day Ethan left primary school, they sat on metal chairs and listened to him play a recorder and watched him hug a teacher. Grace made him a milkshake with strawberries because his smile looked loose with heat. Victoria cried in the car because you never know which milestone will knock the air out of you; she texted the board and said, “I will dial in late,” and did not apologize because this was the kind of power she had rediscovered: the power to say no and make the world bend the way men always assumed it would bend back for them.

On the day Ethan turned twelve, he brought two birthday cards to the breakfast table and handed them out with solemn ceremony: one that said “Mum” and one that said “Grace,” and the words inside were almost exactly the same. Later, at cake, he said a thing nobody rehearsed him to say: “I have more than one kind of mum,” he proclaimed with chocolate on his lip. “I win.”

No one corrected his syntax.

When we tell stories about what saved us, we make them grand. This one was not. It was ordinary in all the hard ways. It was a woman paying attention for the first time the way she had paid attention to stock memos and language around a pivot and pausing in the doorway of a room where a person slept who had once been her project and was now her life. It was a nanny—or if we are refusing to wish women who do this work into namelessness—a caregiver named Grace who did not mistake being needed for being irreplaceable and who was brave enough to be folded into a different role gracefully. It was a husband who came home when he could and shared the hard truth when he should and learned to be loved by a child even when his calendar was a mess.

It was a decision, in a foyer, to cancel a car.

And it was one sentence from a child: You’re the real mummy.

That sentence was both a knife and a scalpel. It cut something open that had been numbed long enough to look functional; it carved away the infection of self-deception. It made the wound raw. It made healing possible.

In the years after, Victoria still did work that made magazines. She still once told her team to deliver a deck at 7 a.m. and then realized she had told them that on a morning when Year 5 had a presentation about Roman Britain; she apologized to grown adults because we learn most from being embarrassed appropriately. She still flew across the ocean some Mondays because doing what you are good at can be part of love, too. People stopped telling her she “had it all” because she stopped performing the version of that sentence that pretends “all” isn’t cruel grammar to impose on a life.

She showed up at school drop-off sometimes in a suit and sometimes in leggings. She stopped saying, “Mommy loves you” into a rectangle and learned how to say it into hair that smelled like the park. She learned not to count time as hours but as presence.

Grace’s contract sat in a folder with a little ribbon on it because Victoria was the sort of woman who liked visual ceremony; it had her healthcare and her leave and a clause about boundaries that said out loud that the work would not swallow her life. Grace took both weeks to go to Jamaica with her mother one year. When she came back, she brought Ethan a paper boat with a painted name. They put it on the piano.

When people asked the women in that house what they had learned, there were two answers that folded into one.

“Children measure love in what you do,” Grace would say, pouring tea.

“Presence is a choice you keep making,” Victoria would say, tapping her phone face-down on the table and leaving it there.

Ethan grew up. He still lined up his toy cars in a neat row until he didn’t, because teenagers put away childhood like summer clothes. He still knew who had held his little life steady and who had decided not to miss it again. He still called both women on Sunday. One of them laughed and said, “How’s my heart?” The other said, “Tell me the truth even if it ruins the business-y version.”

If you asked him, later, when the house had become a story he told rather than a place he slept, what mattered most in the house with the glass, he would not say marble or art or a table that fit thirteen. He would say, “The day Mum stayed home and the day Grace let her.” He would say, “Everyone gets a second chance if they can bear to hear the first sentence spoken.”

He would say, “The house got warmer.” He would say, “That’s how I grew.”

News

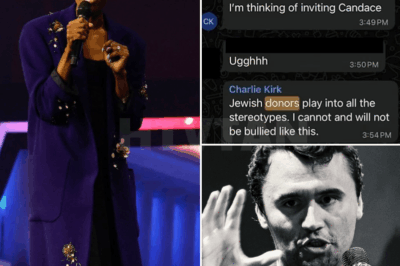

CHAOS ERUPTS INSIDE TURNING POINT USA — Leaked Texts from Candace Owens Just Hit the Wire, the Screenshots Were Published on Owens’ Own Show, Staff Are Scrambling, Alliances Are Fracturing, and Whispers of a Power Coup Are Spreading Fast… But What Was Really Said in Those Messages Has People on the Inside Panicking — You Need to See This Before It Disappears 👇👇👇

After the Assassination: TPUSA Reels from Candace Owens’ Leaked Texts and Legacy Rift In the wake of Charlie Kirk’s tragic…

While I was working a double shift in the ER on Christmas, my family told my 16-year-old daughter there was “no room” for her. She drove home alone to an empty house. I didn’t get angry.

At Christmas, I was working a double shift in the ER. My parents and sister told my 16-year-old daughter there…

For five years, he visited his wife’s grave, certain he knew every detail of her life. Then he found a 6-year-old boy sleeping on the granite slab, holding a photo that shouldn’t exist. What the boy said next rewrote his entire past

A bitter February nor’easter scoured the old burial ground on the outskirts of Willowbrook, Massachusetts, sending plumes of snow swirling…

After 13 years of silence, my son returned the moment he heard I was wealthy! He and his wife arrived with bags packed, expecting to move in. He thought I was the same broken woman he’d abandoned, but he was about to learn a powerful lesson…

The sun rises slowly over the quiet street, painting the porch in warm golden light. Gloria Brooke stands at the…

I came home from my work trip a day early, planning a surprise for my husband. Instead, I found a street full of cars and a party in my own home

The rain hammered against my hotel room window like bullets, each drop a reminder of the storm that had become…

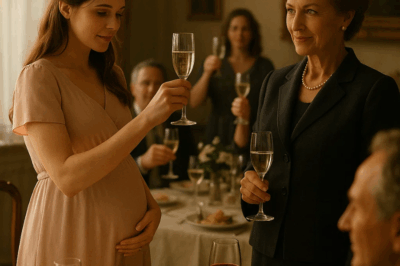

My Mother-In-Law Slipped Something Into My Glass At My Pregnancy Announcement, With A Smile That Hid Pure Betrayal. When I Confronted Her, She Hissed, ‘My Daughter Deserves To Give Birth First—Not Some Outsider.’ I Quietly Switched Glasses With Her Precious Daughter During The Toast… And Then Everything Fell Apart.

Part 1 – The Toast My name is Sarah, and I’ve been married to my husband, Jake, for three years….

End of content

No more pages to load