The first time they heard about the American carriers, most of the officers in the Kriegsmarine laughed.

It was early in the war, when the Atlantic still felt like a German hunting ground and U-boats slid through the dark like knives. In wardrooms from Kiel to Brest, the image of sea power was fixed: battleships were kings, cruisers were queens, and submarines were the silent assassins that would strangle Britain into submission.

Aircraft carriers? Those were curiosities. Support vessels. Floating airfields for reconnaissance and the occasional nuisance raid. British ones were small, lightly built, clearly vulnerable. One solid hit from an 8-inch shell, they said, and the whole experiment would go up in smoke. The sea was ruled by armor and gunnery, and that was that.

Reality took its time, but it came.

At first, it arrived in odd patrol reports from the U-boat arm. Captains came back from the mid-Atlantic with strange stories in their logs: aircraft appearing hundreds of miles from land, engines snarling overhead where there should have been only sky and sea. Convoys once easy to stalk now seemed wrapped in an invisible shield of air cover.

Berlin’s analysts dismissed these accounts as exaggerations from men who had been at sea too long.

“There must be some island base,” one staff officer insisted, tracing his finger over maps. “Or a trick with long-range patrol planes. They cannot keep aircraft over convoys this far out.”

Then the rumors hardened into fact. A U-boat surfaced at periscope depth and glimpsed a silhouette on the horizon—too long, too level, too flat to be anything but a flight deck. Not a small escort carrier, either, but a proper giant. A floating airfield nearly as large as Bismarck, and bristling not with heavy guns but… airplanes.

To men who had memorized the thickness of armor belts and the caliber of main batteries, it sounded absurd. How could such a ship survive without real guns? How could aircraft possibly replace a salvo of 15-inch shells?

The Atlantic began to answer.

Suddenly, the hunters were being hunted. U-boat commanders described a new terror: the persistent buzz of aircraft engines, the shadow that flickered across the waves before depth charges thundered into the depths. Patrol areas that had once been safe hunting grounds became killing zones. Boats were forced to dive early, attacks aborted, entire patrols ruined by planes that seemed to come from nowhere.

They didn’t come from nowhere.

They came from carriers.

The war in the Pacific drove the lesson home with brutal clarity.

Reports from Japan, passed through liaison officers and intelligence channels, sounded at first like nightmares or lies. At Midway, they said, four of Japan’s fleet carriers had been sunk in a single battle. The ships had never even seen their enemy. No gunnery duel, no thunderous broadside—just waves of aircraft launched from over the horizon, trading blows across hundreds of miles of empty ocean.

To German admirals raised on Jutland and Tsushima, this was almost heresy. A battle in which battleships barely fired? A fleet destroyed by planes launched from decks the size of parade grounds?

But the Japanese were not prone to self-humiliation. Their documents and quietly bitter officers told the same story: in a carrier war, the first to locate and strike decided everything. Armor and gun range mattered less than flight decks and hangar capacity.

Still, hearing and believing are not the same as seeing.

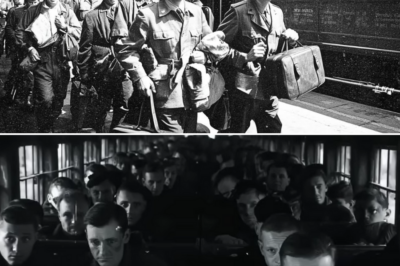

That came later, when German sailors and officers began to be captured and, on their way to prisoner camps, found themselves briefly aboard the very monsters they had once scoffed at.

One such officer—once proud of his posting in the surface fleet, now a prisoner escorted by US Marines—remembered the moment the launch boat drew alongside the American carrier.

“I thought at first it was two ships moored together,” he wrote years later. “Only when I saw the continuous line of the deck did I understand it was one.”

The flight deck seemed to stretch into the horizon, a broad, gray prairie alive with motion. Sailors in colored shirts moved like pieces in a choreographed game—yellow directing aircraft, red handling ordnance, blue towing planes, green crouched by catapults. Engines rumbled underfoot. A Hellcat sat at the catapult, wings folded down. To the German’s eye it looked less like a machine than a waiting animal.

Below decks, the impression grew stronger. The hangar bay was not a mere shelter for a handful of planes; it was a hangar cathedral, a steel cavern with rows upon rows of aircraft. Mechanics swarmed over them with tools and fuel hoses, checking, fixing, arming. He thought of German navy bases where every airworthy machine was treated like a precious object. Here, aircraft were like shells in a magazine—serviced, fired, recovered, and fired again without ceremony.

“We believed war at sea was decided by bold maneuvers,” he wrote. “Here, I saw something different: war as a factory process. Everything routine, everything drilled, nothing left to improvisation.”

When the flight operations alarm rang, the ship transformed. Planes rolled into position. Fuel lines were disconnected. Bombs latched home. Pilots clambered into cockpits. In minutes, the flight deck became a storm of propellers and exhaust. One by one, aircraft surged forward and leapt into the air. The carrier’s guns never fired a shot. Its weapon was in the sky.

The scale was not just physical, it was industrial.

German shipyards agonized for years over a single capital ship. Each battleship launched was a political event, a symbol of national pride. Across the Atlantic, Essex-class carriers were sliding down the ways in what seemed like steady rhythm.

“They build them as we build trucks,” one U-boat officer noted after his capture. “We finish one ship and celebrate. They launch three and go back to work.”

By 1943, American yards were commissioning carriers faster than Germany could replace lost submarines. Escort carriers followed convoys like shepherd dogs. Fleet carriers roamed far oceans, their location a constant question mark in every operations room in Berlin.

To the men who had once trusted in Dönitz’s promise that U-boats would starve Britain—for whom the ocean had seemed a hunter’s realm—this new reality tasted like ash. Every surface they crossed could be under unseen aerial patrol. Every radio transmission risked triangulation and a carrier’s sudden fist from the sky.

Even the most doctrinaire officers felt their faith shifting.

One commander wrote in his diary, bitterly, “We trained for the old war. The new war belongs to whoever controls the air above the water. The sea is no longer ours. It belongs to whoever brings his runway with him.”

The carriers did more than sink ships. They sank illusions.

They showed German officers that the United States was not winning simply because of “numbers” or “luck,” as propaganda had liked to claim. It was winning because it had chosen a different path: to fuse industry, technology, and doctrine into a system that turned steel and fuel into decisive, global power.

The battleship age was ending not with a single apocalyptic engagement, but with a series of awakenings in the minds of men who had spent their lives believing in armor and gun caliber.

Some wrote memoirs afterward. Most did not. But in interviews and fragments of letters, the same images surfaced: the deck that seemed to go on forever, the hangar filled with planes, the calm rhythm of launches and recoveries, the sense that these ships were not exotic experiments but perfected tools in the hands of people who knew exactly what they were doing.

And beneath it all, a realization like a slow, cold tide:

We were wrong. The future of sea power is not the ship that fires the biggest shell, but the one that sends the most aircraft into the sky.

By war’s end, those captured officers sat behind barbed wire in Arkansas, Oklahoma, or Scotland and listened to news of operations across the globe: U-boats hunted down by carrier groups, convoys safe under constant air cover, Pacific islands reduced by carrier strikes without a single battleship shelling the beaches.

The ocean they had imagined as a chessboard had become something else—less like a game, more like a grid under glass on which aircraft traced invisible lines.

They had gone to sea expecting to fight the last war. The Americans had built the tools for the next one.

And in their memories, long after uniforms were taken away and flags lowered, one image remained:

A horizon-wide deck of steel, humming with power, launching wave after wave into a sky that no longer belonged to anyone else.

News

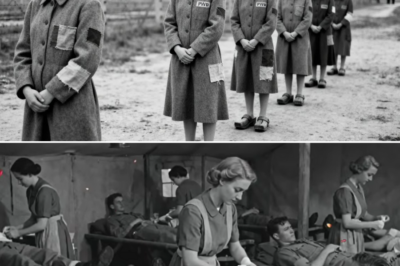

(CH1) German POW Nurses Said: “You Treat Us Well, How Can We Help?” — “Heal Our Wounded”, Said The General

When the trucks stopped at Camp Rucker, the Alabama sky looked wrong. It was too big, too blue, too indifferent…

(CH1) Captured German Nurses Were Shocked With American Medical Abundance

The first thing that hit her was the smell. Not blood, not gangrene, not the sour stench of bodies crammed…

(Ch1) When German POWs Reached America They Saw The Most Unexpected Thing

The first thing that hit him was the smell. Not coal smoke or cordite or the sharp bite of disinfectant…

(Ch1) Female German POWs Didn’t Expect New Shoes—and Socks—in America

The order came in English first, then in rough, accented German. “You’ll remove your shoes now.” The voice was flat,…

(Ch1) He Taught His Grandson to Hate Americans — Then an American Saved the Boy’s Life

January 1946, the war was over, but the ground still killed. In a ruined German city, American combat engineer Paul…

(Ch1) This 19-Year-Old Was Flying His First Mission — And Accidentally Started a New Combat Tactic

By the winter of 1943, the sky over Europe was killing American pilots faster than the factories at home could…

End of content

No more pages to load