Part I — The Text

The message arrived between a zoning call and an email about a retaining wall design, twelve blunt words that landed like a brick: “This year, just your brother’s family.” I stared at my phone until the screen dimmed and my reflection floated over the bubble—thirty-three years old, CEO hair, coffee-stained smile. I typed the only reply that didn’t require permission or apology.

Enjoy.

I didn’t walk to the window and gaze dramatically out over the city. I don’t do movie beats. I refilled my water, finished the call, clicked “send” on the retaining wall email, and then shut my office door. For ten minutes, I let myself be sixteen again—the child who used to count the creek minnows behind our house in suburban Colorado because fish didn’t rank children. The ache was old and familiar, as dependable as our split-level’s ticking baseboards in winter.

We were the kind of middle-class that bought cereal when it was two-for-one and went out for dinner when a team won. We had a four-bedroom, a swing set that splintered palms, and a kitchen that smelled like lemon oil every Sunday. It was idyllic in the ways that lull people into thinking nothing sharp lives there. Except favoritism is a blade you don’t see until you bleed.

My father, Harold, adored my older brother, Jason, with a crispness that made photographs easy: Jason in the center, me at the edge. Jason got the latest console; I got socks and a “you’ll love that they’re warm.” He sat through doubleheaders of Jason’s baseball with a thermos and a folding chair; he missed my volleyball championship because “work ran long.” At dinner, he’d ask Jason about pitches and GPA and friends; he’d ask me to pass the salt.

My mother, Diana, made it bearable. She drew elaborate posters for my science fair boards and bought me milkshakes after losses. She called my essays “clean knives.” She taught me how to do a budget in pencil because life smudges. When pancreatic cancer took her quickly—six months from diagnosis to funeral—our house stayed lemon-scented and ceased to be home. Without her, favoritism forgot it was supposed to hide.

Harold threw Jason an eighteenth birthday party at a steakhouse with linen napkins and a slideshow. He bought me pizza and tucked fifty dollars into a drugstore card for mine. He flew Jason to five college tours. I took the state university because “it makes financial sense.” I wrote scholarship essays in a dorm laundry room that smelled like bleach and ambition. I worked twenty hours a week at the bookstore and kept a 3.9 in business. Summers, I interned. I built a resume that didn’t mind if no one framed it.

Jason drifted. He wore Dad’s old fraternity letters and learned how to shake hands with people who already liked him. He cycled through majors and then jobs he insisted were “bad fits” when they didn’t fit him. Harold found a way to treat his mediocrity like raw genius: It just needed time.

I didn’t wait on time. I found a job in real estate development and then built the kind of life you have to teach your body to believe you deserve. I saved aggressively, invested modestly, and—through a networking group—put small checks into tech startups. One exit multiplied my money thirtyfold; two more turned “modest” into “quietly wealthy.” By twenty-eight, my net worth would have flipped our family’s script if I’d handed out copies. I didn’t. Years of having good news redirected to Jason taught me better.

We did Thanksgiving the same way every year: Harold carved, Jason toasted, people pretended my store-bought pie was unsophisticated and Jason’s store-bought pie was “so thoughtful.” Last fall, I mentioned closing a seven-figure property deal and Harold asked when I’d settle down and “do what your brother’s doing.” At the time, Jason was on his third career change. I drove back to my downtown apartment and called my agent. The ranch I’d toured the prior weekend had been sitting in my chest like a seed. “Make an offer,” I said.

The 120-acre property two hours from Denver did not need my approval to be beautiful. The main house wore stone and glass like an apology to the view—floor-to-ceiling windows, a kitchen that would make a chef swear allegiance, a great room that could seat twenty under rough-hewn beams. Three guest cabins peeked out from the trees, gable roofs crisp against a mountain sky that changed moods faster than people do. I renovated judiciously: double ovens, a six-burner range, a pantry large enough to mourn in, a dining table milled from a single redwood slab. I put a long fire pit out back for nights the stars felt generous.

I told no one in my family. The ranch became my sanctuary. My friends knew. They came for long weekends and split their ankles on the trail because the altitude told them they weren’t special. We cooked, we read, we slept, we looked up.

Three weeks before Thanksgiving, Harold’s text arrived like a ritual gone sour. This year, just your brother’s family. I did the polite thing, typed Enjoy, then called my therapist, Dr. Marilyn. She took me without an appointment because there are sentences that rearrange the bones of a day.

“This is a significant boundary,” she said, and then asked the question she always asks when my father chooses Jason under a different excuse: “What response respects your worth?”

Begging did not. Explaining did not. Asking why did not. I sent Enjoy again in my head and took the next day off. I walked the park watching fathers hoist toddlers like trophies, then went home and wrote letters I would never send: Dear Dad, I wonder if you know what it feels like to be the second question in a house where you helped write the rules. I didn’t send them. The point wasn’t to teach him. It was to stop teaching myself to wait.

I planned to take the ranch alone for the holiday. A small turkey breast, a bottle of wine, a hike in the thin air to remind me I could keep going even when my breath didn’t want to. Then my cousin Julia called to ask if we were “doing Harold’s as usual.”

“Actually,” I said. “He’s keeping it small. Just Jason.”

Silence clicked once on the line. “He didn’t say that to Aunt Margaret,” Julia said. “We…haven’t heard anything.”

I felt something steady itself inside me. “Come to the ranch,” I said. “Bring the kids. There’s room.”

“You have a ranch?” she said, halfway between delight and accusation.

“Eighteen months now,” I said. “It’s…good.”

By the time we hung up, my fingers were already opening a notes app. Uncle Frank and Aunt Margaret; Aunt Barbara and William; cousins; college friends with families far away; work friends who’d said “no real plans.” The list grew. So did the logistical flags. Sleeping: sixteen in the main house and cabins if I used every bed and couch with dignity; everyone else at the inn fifteen minutes down the road where the owner would be thrilled to have a holiday surge. Food: cater the backbone, let family recipes fill the ribs. Rentals: tables, chairs, linens, place settings. Flowers, candles, a photographer for candid grace because we’d never had that before.

I booked the catering company I trusted and heard the miracle sentence every host hopes for three weeks out: “We had a cancellation.” I booked rentals and housekeeping and a florist who didn’t overdo it. I made welcome baskets—local chocolates, a small bottle of Colorado bourbon, wool socks that invite naps, handwritten notes that didn’t sound like they’d been copied from Pinterest. I scheduled guided hikes and horseback rides for the kids, puzzles and cards and a movie lineup for the full-bellied afternoon lull. I hired a photographer for Thanksgiving Day because memory is often cruel; it helps to bind it in something honest.

When the digital invitations went out—photos of the ranch in summer and winter, a simple note that said everything’s taken care of; bring yourself and a recipe if you like—responses came back like birds. We’d love to. We had no idea. We’re proud of you. We miss you. College friends said, We’ll rearrange. Work friends said, We were waiting for an excuse to skip our in-laws. Within twenty-four hours, twenty-eight names were on the spreadsheet. The number felt less like arrogance and more like math—how many chairs, how many forks, how many hours for the dishwasher to reset a room.

Jason texted to check if I was “okay with not coming.” Dad, he said, had told him I was busy with work. It took restraint not to screenshot truth. I replied I’m fine. Have a nice holiday, and put the phone down as if it were capable of growing teeth.

The ranch held my anxiety the way the mountains hold the weather—briefly, then with decisive shrug. On Tuesday, Julia’s SUV pulled in first. Kids spilled out, Julia hugged me, her husband whistled. “You’ve been holding out,” Mark said, looking up at the glass. I showed them the rooms. The children fell onto window seats and announced they were never leaving. Uncle Frank arrived late afternoon, took off his glasses to clean them like men do when the world is better than they deserve, and said, “Harold never said a word.” He hugged me like his arms remembered a child he hadn’t defended properly.

By nightfall, the kitchen felt like a place without a history of tight shoulders. Aunt Margaret buttered rolls like a prayer. My college friend Natalie unboxed a pumpkin cheesecake like treasure. We ate soup around the fire pit, our noses pink, our laughter unscheduled. On Wednesday the rest poured in—work friends bearing Malbec and napkins; cousins with casseroles named after grandmothers; children like tiny ambassadors asking if they could get lost yet. We did a taco bar and dented the ice with bottles and danced in wool socks to old songs that do the good kind of ache.

Aunt Barbara found me at the sink and said, “Harold called William to ask where we were going.” She smiled like someone who eventually chooses her niece over her brother. “I told him the truth. He said he didn’t know you owned land.” She squeezed my shoulder. “You don’t owe him a tour.”

“Thanks,” I said. I meant for choosing, not for telling.

Thanksgiving morning was rude with blue sky and crisp cold. The caterers arrived, quiet and competent, and set about turning a plan into a meal. We hiked late morning through aspen and pine to a rocky outcrop where the view made people forget their age. The photographer captured a group shot—thirty people with cheeks like apples, mouths open in true smile. He captured Aunt Barbara laughing like she hadn’t in a decade, Uncle Frank holding a thermos like communion, Julia’s kids inventing a game no screen could manage.

At four, we lifted champagne for a toast. Uncle Frank, as oldest, spoke first. “To Elena,” he said—(I insist on Elena at work, but among family, I’m still Alina—don’t ask me why; that’s a different essay)—“for bringing us together in this beautiful place. And to all of us, chosen and stubborn and generous, may we be grateful for who is here instead of keeping score about who isn’t.”

Dinner was buffet, three turkeys carved by three volunteers who did not need to be Harold to make a breast taste like thanks. We sat at three tables arranged so everyone could see everyone else. The food was enough and then some. The grace wasn’t the kind you force.

After pies and a brief detour into a spontaneous argument about whether chess counts as a sport, we moved into games, music, naps, and nothing. At some point on the back deck, cousins Julia and Martin joined me with their glasses. “Best Thanksgiving in years,” Julia said quietly. “No judgment.” Martin nodded. “I didn’t realize how much I dread Harold’s until now.” He laughed. “I thought it was just me.”

“It’s never just you,” I said. And then we watched the kind of stars that make you feel less special and more held.

I fell asleep that night in a house with the soft noises of people who know they’re wanted. For the first time in memory, I didn’t dream about being left out of a photograph.

On Friday morning my phone buzzed itself into a headache. Six missed calls from my father, three from Jason, one voicemail from Harold so tight with outrage it whistled. “What exactly do you think you’re doing hijacking our family Thanksgiving? Call me back immediately.” Other relatives reported similar calls. The family group chat I ignore for my mental health lit up with confusion and accusation. Uncle Frank called to say he’d told Harold the obvious: you didn’t invite us; Elena did. Harold claimed he’d planned a “big family dinner the following weekend” like that was an established tradition instead of a newly invented alibi.

That evening, with my friends as witnesses, I put Harold on speaker.

“Since when do you own property in the mountains?” he opened, forgoing hello. “Who told you you could invite the entire family?”

“You specifically told me you were keeping it small,” I said evenly. “Those were your exact words.”

“That was for the day,” he said. “We always do the big dinner after.”

“We never have,” I said. “Also, you didn’t invite me to either version.”

Jason clicked in. “You’re being ridiculous,” he said, a sentence he’s favored since he learned how to make women smaller with words. “Dad was giving you a break. You always complain about family stuff.”

“I’ve never complained about attending,” I said. “I’ve complained about being treated like a visitor.”

“See?” he said. “Always about your feelings. Some of us just want a normal holiday.”

The irony was enough to choke a mountain. I kept my voice easy. “A normal holiday is one where everyone who wants to be loved is invited.”

“You’re showing off,” he snapped. “Flaunting money to make Dad look bad.”

“No one knew about my money,” I said. “They know now because they were here.”

Harold took the wheel again. “You’ve embarrassed me.”

“I was hurt,” I said. “We each made choices.”

We circled the same three squares. Jason accused; Harold lamented his image; neither asked how it felt to read a dozen words that confirmed what a childhood had taught. I refused to fight at a volume chosen for me.

Afterwards, Amanda texted. The ranch looks amazing. The kids want to visit. She added in a second bubble, quieter: Your dad told us you were too busy to come. I didn’t know he…uninvited you.

It is something to receive an olive branch from someone who benefits when you’re not in the room.

Over the next days, photos floated onto timelines with captions like “Best Thanksgiving ever” and “Mountain magic”. I didn’t curate. Harold could feel excluded by his own choices in real time.

In therapy the following week, Dr. Marilyn said, “You maintained boundaries without inviting chaos.” She has a way of making basic decency sound like a new dialect. “How do you feel?”

“Lighter,” I said. It surprised me to hear it. “I think I finally set down the job of earning something he doesn’t sell.”

The most unexpected message came from a shared tablet belonging to Ethan and Lily. Aunt Elena your house looks so cool. Mom showed us. Can we see the horses? That’s how family actually changes. Not with declarations, but with requests to pet something that can kick you if you stand in the wrong place.

I still went to my father’s on Christmas Eve. I stood in his living room for two efficient hours because that is a boundary that keeps the peace without handing out my power. He said, “I had no idea you could afford a place like that.” I said simply, “I’ve done well.” He said, “You might have told me.” I asked, “Would it have mattered?” His silence felt like honesty finally getting a line.

At my ranch on Christmas Day, the house held a smaller crowd and a bigger quiet. We did a cookie contest, a snowshoe hike that made everyone admit air is a gift, and a Secret Santa that resulted in Cousin Martin wearing a sweater with a llama that played “Jingle Bells.” Jason asked me to lunch, just us. He admitted the kids wouldn’t stop asking about the ranch. He said, without Amanda or Harold in the room, that he hadn’t thought about what it would feel like to be told not to come. He did not apologize. He did not have to—for the first time, he had considered a feeling that wasn’t his.

When Dr. Marilyn visited in January (I invited her because therapists enjoy seeing where the work lands), she asked what had changed most. We walked the property past aspens that keep their white bark like a secret, and I surprised myself by answering easily. “I stopped auditioning,” I said. “I don’t send him my resume anymore.”

A letter from Aunt Margaret arrived with handwriting that belonged to holidays when my mother still stood at the stove. Your mother would be so proud, she wrote. Not because of the house. Because of the table you set. Harold had been many things since Diana died; balanced was never one of them. “It doesn’t excuse,” she wrote. It explains. People think explanation is for the guilty. It is, often. It’s also for the child inside an adult who needs to stop internalizing other people’s unfinished grief.

By February, a new tradition had formed: second-Saturday suppers for cousins and friends who passed through Denver on skiing weekends. The table filled with the sound of people who don’t have to earn their chair. I sent thank-you notes for Thanksgiving. I sent invitations for summer. I made plans for next November. The doors will be open. The table will be wide. There’s always a seat for a person who says, “I didn’t think I’d be here.”

If you’re reading this from a couch that isn’t yours, from a kitchen that still smells like a childhood you don’t want anymore, from a hotel room on a holiday because your version of family requires distance—drop a comment, tell me where you are, tell me what you made yourself for dinner. Sometimes rejection is a door you’re supposed to close from the outside so you can build one that swings both ways. Sometimes the family you choose is the one that finally teaches you how to love without a double-entry ledger.

Enjoy, my father texted back on Christmas night. I smiled. It turns out I finally did.

Part II — The Table

By the second week of November, I had memorized the view from the porch swing: late-golden light slanting between aspen trunks, snow flirting with the grass but not committing, and the kind of stillness that doesn’t ask questions. The fire pit sat unused but ready. The guest cabins were stocked. Inside the main house, the table waited, long and heavy and honest—redwood polished to a soft sheen, wide enough for elbows and secrets.

The invitations had gone out two weeks prior, digital cards with photos of the ranch and a simple message: If you have nowhere to be, come here. If you do, and you want to change your mind, come here anyway. I didn’t mention Harold. I didn’t need to.

The responses came with a mix of joy and hesitation. Cousin Julia replied first: Are you sure? We have a lot of chaos. I answered, Bring it. The mountains can handle it. Aunt Margaret, always gracious, sent a photo of her pumpkin bread cooling on the windowsill. My college friends asked if they could contribute sides and music and the energy only people with no kids bring to long weekends.

By the Monday of Thanksgiving week, the ranch began to fill. Julia’s kids barreled into the snow-dusted yard like they were born for it. Uncle Frank arrived with a bottle of whiskey and a quiet pride I hadn’t seen on his face before. The fire pit finally lit, and so did something in me.

The kitchen became the heart, as kitchens do. It absorbed anxieties and released smells that settled in your clothes and made you okay with that. Aunt Barbara brought her grandmother’s cranberry relish. Tamara from work brought wine and a story about a terrible date that made everyone gasp and laugh in equal measure. By Wednesday night, the dining table was surrounded by twenty-eight people who had all once been background characters in Harold’s version of family, now foregrounded by proximity, warmth, and choice.

We hiked Thanksgiving morning—not all of us, just those willing to pretend they weren’t winded by the first incline. The overlook gave us a view worth every frozen lung: sharp mountain peaks cut against a sky so blue it looked deliberate. Someone took a group photo. Everyone smiled like no one had told them to.

Dinner was at four. The caterers plated three turkeys, each with its own personality: classic roast, deep-fried bravado, and one glazed in maple and risk. Side dishes came from every generation and every kind of palate. The table held stories, too—a napkin ring shaped like a moose from a trip to Banff, Aunt Margaret’s gravy boat that had survived four family moves, a centerpiece made by Julia’s daughter entirely out of pinecones and stubbornness.

We ate. We toasted. We paused.

Uncle Frank stood, cleared his throat, and said, “To Alina, for setting a table wide enough for the people who show up.”

I didn’t cry then. I waited until later, when the dishwasher hummed and the last slice of pecan pie had disappeared and the fire crackled just loud enough to hide it.

Harold never texted that night. Jason didn’t call. Amanda posted a photo of the kids eating leftover stuffing with a caption that read, Hope everyone had a cozy Thanksgiving. That was the closest anyone came to acknowledging the shift.

The following weekend, I hosted a second gathering—smaller, quieter, mostly local friends who hadn’t made it to the main event. We made chili, played board games, and watched snow begin to gather properly. The ranch took it all in, like it had been waiting to be filled this way.

A week later, a letter arrived from Aunt Margaret. She wrote, Your mother would have loved this place. She would’ve made everyone wear matching flannel and insisted on singing after dinner. She ended with, You’ve made something sacred here.

That line stayed with me.

By Christmas, Harold sent a printed card—a performative apology in cardstock. It said I was invited to Christmas Eve dinner. I went. I stayed ninety minutes. I smiled at Jason’s kids. I accepted a slice of ham. I left before the second glass of wine, before the questions turned invasive, before Harold could turn my presence into an anecdote. On the drive home, I didn’t feel regret. I felt sovereignty.

New Year’s was at the ranch. Ethan and Lily visited. We made pancakes and built snow forts. I taught them how to make hot chocolate from scratch. They called it “Aunt Alina’s potion.” Jason texted to say thanks. He didn’t ask questions.

Spring came slow to the mountains, but it came. I planned the summer gathering: open-air movies, wildflower hikes, watermelon on the porch. People marked their calendars early. They wanted to come back. Not just to the place, but to what we built inside it.

That summer, I stood on the same porch swing where it all started, coffee in hand, the air sweet with pine. The table inside still held its shape. It had been scrubbed, sanded, spilled on, and set again. That’s what real things do. They last.

And now, every year, we gather.

Not to prove a point. Not to fill a silence. But because we can.

Because we choose to.

Because this is our table now.

And there’s always room for one more.

News

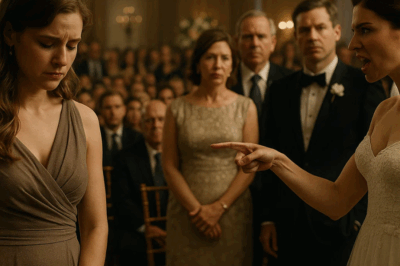

(CH1) At my brother’s wedding, his bride humiliated me in front of 150 guests

At my brother’s wedding, his fiancée slapped me before 150 guests for refusing to give up my house. My family…

(CH1) Millionaire gets maid pregnant and abandons her. When he meets her again 10 years later, he regrets it immensely…

Millionaire gets maid pregnant and abandons her. When he meets her again 10 years later, he regrets it immensely. It…

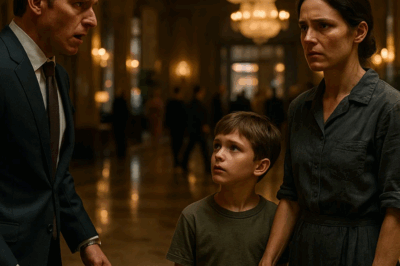

(CH1) Little Girl Sob And Begging “ Don’t Hurt Us”. Suddenly Her Millionaire Father Visit Home And Shout…

In the heart of New York City, where the skyline glimmered with the promise of wealth and success, a man…

(CH1) Old biker carried the paralyzed veteran on his back for three miles through the Veterans Day parade when the city refused to make it wheelchair accessible.

When the City Failed Him, This Biker Carried a Paralyzed Veteran Three Miles Sometimes the most profound acts of brotherhood…

(CH1) My Sister Cut Me Off for 8 Years as ‘Trash’—Then I Won $30M Lottery and Bought an OCEANFRONT MANSION

What Wasn’t the Prize PART I — The Room for Trash The sun hadn’t fully risen over Baton Rouge, but…

(CH1) My Parents Asked the Security Guard to Kick Me Off the Yacht — Not Knowing I Own the Entire Chain

PART ONE: UNDER THE SURFACE The wind at the marina wasn’t particularly strong that afternoon, but it had that slick,…

End of content

No more pages to load