PART I: THE MATH OF DEATH

At 6:47 p.m. on October 14th, 1943, Colonel Cass Sheffield Huff stood on the edge of the flight line and counted ghosts.

The bomber stream came back in pieces.

B-17 Flying Fortresses limped in low and slow, engines coughing, skin shredded, holes punched clean through aluminum that had been built in Detroit, Wichita, Seattle. Some aircraft landed missing entire control surfaces. Others touched down with landing gear half collapsed, crews praying the wheels would hold for just a few more seconds. Ambulances waited at the hardstand. Fire trucks idled with engines running. Medics watched the sky, already exhausted, already knowing there would not be enough stretchers.

Huff did not look at the aircraft.

He looked at the spaces between them.

Sixty B-17s had been scheduled to return from Schweinfurt.

Thirty-nine did.

Seventeen more had landed elsewhere, so badly damaged they would never fly again. One hundred twenty-one returned with battle damage severe enough to require weeks of repair. Six hundred American airmen were dead or missing in a single day. The loss rate stood at twenty percent—double what planners considered the absolute limit of sustainability.

At that rate, the Eighth Air Force would be gone in months.

Huff was thirty-nine years old. He had spent two years commanding the air technical section. He had spent nine months watching this exact pattern repeat itself. And he had no solution.

American bombers flew deep into Germany in daylight. Their escorts—the P-47 Thunderbolts—turned back at the German border when their fuel ran out. Luftwaffe fighters waited patiently beyond that invisible line. Once the escorts peeled away, the Germans swarmed.

The results were always the same.

Huff had tested modifications. He had evaluated tactics. He had pushed every fighter type to its theoretical limit. The Thunderbolt was tough and powerful, but it drank fuel too fast. The P-38 Lightning had range on paper, but lacked reliable external tanks. The new P-51 Mustang was promising, fast, agile—but without external fuel, it could not reach Berlin.

And aluminum was gone.

Every pound of it was already spoken for—bombers, fighters, tanks, ships. There was no excess capacity. No margin. No room for new metal drop tanks, no matter how desperately they were needed.

Huff understood this problem in a way most officers did not.

He had not grown up in the Army Air Forces.

He had commissioned directly from civilian life in 1938, leaving behind his role as vice president of Daisy Manufacturing Company—the BB gun business. He understood production lines, materials shortages, quality control. He knew how to build things cheaply, quickly, and in enormous quantities.

And standing on that flight line, watching men stagger out of aircraft that should never have made it home, he realized the problem was not aviation.

It was manufacturing.

That night, long after the engines had gone quiet, Huff sat alone with a stack of reports and a single, stubborn thought.

The British had tried something.

Something the Americans had laughed at.

Paper fuel tanks.

The Royal Air Force had experimented with craft-paper tanks on Spitfires. They had leaked. They had cracked at altitude. They had failed quality tests. General Ira Eaker had tried similar tanks on P-47s and declared them unsatisfactory.

The verdict had been unanimous.

Absurd.

Huff stared at the reports and felt something tighten in his chest.

They had failed—but why?

The British tanks leaked because they were poorly made. The glue failed. The paper delaminated. The tanks burst when dropped because no one had engineered them for controlled jettison. These were manufacturing failures, not conceptual ones.

Paper was cheap.

Paper was available.

Paper did not require aluminum.

And if paper could be made strong enough, flexible enough, reliable enough, it could solve the escort problem permanently.

Huff did not ask whether paper should work.

He asked whether paper could work.

By late October 1943, he began working in secret.

His specifications were unforgiving.

The tank had to hold 110 gallons of high-octane aviation fuel. It had to survive 30,000 feet of altitude, temperatures from minus forty to one hundred degrees Fahrenheit. It could not leak. It could not rupture. It had to be lighter than metal and cost a fraction as much.

Failure was not an option.

He partnered with Bowater-Lloyds, a paper mill in London that had experience laminating industrial craft paper. Together, they experimented with layers of paper bonded using resorcinol glue—a waterproof adhesive already proven in aircraft construction.

The result looked laughable.

A dull brown shell, one-eighth of an inch thick.

But it worked.

The laminated paper distributed stress instead of concentrating it. The glue remained flexible at extreme temperatures. The tank held fuel without seepage. It absorbed vibration instead of cracking.

By December 1943, the first tanks were flying on P-47 Thunderbolts.

Pilots were openly hostile to the idea.

Flying into combat with paper strapped under your wings felt suicidal. But the tanks did not leak. They did not burst. When jettisoned, they tumbled away cleanly, disintegrating harmlessly.

Production ramped up.

Fifteen tanks per day. Then thirty. Then sixty.

Huff sent samples to Wright Field in Ohio for formal evaluation.

Two weeks later, the verdict arrived.

Absolutely unfeasible.

The report recommended immediate cancellation of the program.

By the time Huff read it, Eighth Air Force fighters had already flown over fifteen thousand sorties using paper tanks—without a single operational failure.

Huff ignored Wright Field.

He went straight to Major General James Doolittle, who had just taken command of the Eighth Air Force.

Doolittle understood the math instantly.

Every paper tank meant one more Mustang could go four hundred miles deeper into Germany. Every Mustang over Berlin meant fewer Luftwaffe fighters attacking bombers. Fewer fighters meant lower losses. Lower losses meant the bombing campaign survived.

Doolittle authorized mass production.

The paper tanks weighed eleven pounds empty. A metal tank weighed forty-two. The paper version cost eight dollars to build. Metal cost sixty-three. Six paper tanks could be produced for the weight and price of one metal tank.

And paper did not compete with aircraft production.

Britain had trees.

By February 1944, Bowater-Lloyds was producing two hundred tanks per day.

They hung under the wings of P-51 Mustangs across England.

Each added 110 gallons of fuel.

London to Berlin.

And back.

On March 4th, 1944, sixty-eight P-51 Mustangs escorted bombers all the way to Berlin for the first time.

The Luftwaffe could not believe it.

The escorts did not turn back.

They stayed.

They fought.

Bomber losses fell to 3.2 percent.

The war changed that day—not with explosions, not with speeches, but with craft paper and glue.

And Cass Sheffield Huff stood quietly behind it all, already working on how to make more.

PART II: RANGE IS POWER

The first escort to Berlin did not feel historic while it was happening.

For the pilots strapped into P-51 Mustangs, it felt wrong.

They were trained—conditioned—to expect the turn-back point. Somewhere over western Germany, a fuel gauge would dictate reality. Escorts always peeled away. Bombers always went on alone. That expectation had shaped Luftwaffe doctrine and American psychology alike.

On March 4th, 1944, the fuel gauges kept moving.

Colonel Donald Blakeslee led the Fourth Fighter Group, sixty-eight Mustangs climbing steadily through twenty-five thousand feet over the English Channel. Two paper tanks hung under each wing, dull brown against polished metal. The aircraft felt heavier, slower in roll, but stable. Fuel flowed smoothly from the external tanks into the Mustang’s system. No leaks. No vibration.

They crossed the Dutch coast.

Still no turn-back call.

The bomber stream came into view over Hanover—hundreds of B-17s stretched across the sky in rigid formations. Normally, this was where escort coverage thinned. Normally, German fighters waited ahead, conserving fuel and strength for the moment the Americans were exposed.

But this time the escorts stayed.

German radar operators reported something impossible: American single-engine fighters advancing with the bombers, deep into the Reich. Staffel commanders hesitated. Some pilots believed the reports were wrong. Others assumed the Mustangs would turn back any moment.

They did not.

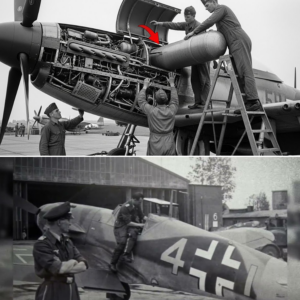

Over Berlin, the Luftwaffe scrambled everything it could put into the air—Messerschmitt 109s, Focke-Wulf 190s, older aircraft pressed into service by necessity. They expected to fight bombers.

Instead, they met Mustangs.

Seventeen German aircraft fell that day. The bombers took losses—nine out of two hundred eighty—but nothing like Schweinfurt. The difference was unmistakable.

Back in England, bomber crews talked about it in stunned tones.

“They stayed,” one gunner said. “All the way in. All the way out.”

For Huff, the Berlin mission answered one question and raised a dozen more.

Range was no longer theoretical.

It was operational.

But the paper tanks still faced their most dangerous unknown: endurance.

Nobody knew what craft paper soaked in aviation fuel would do after hours at extreme altitude. No one had data on prolonged exposure to minus forty-degree temperatures at thirty-five thousand feet. Engineers worried the resin would crack, the paper would become brittle, the fuel would gel or leak.

If that happened over Germany, the result would be catastrophic.

The test came on March 8th, 1944.

Mustangs from the 357th Fighter Group launched on an escort mission to Berlin expected to last eight hours gate-to-gate. The fighters climbed to thirty-six thousand feet. Outside air temperature dropped to minus forty-eight degrees Fahrenheit. The paper tanks had already been hanging under the wings for ninety minutes before takeoff, fully loaded, coated in morning frost.

The predictions were grim.

The paper would crack.

The glue would fail.

The tanks would rupture.

None of it happened.

The laminated shells flexed with temperature changes. The resorcinol glue remained pliable. The craft paper distributed stress evenly instead of fracturing. Fuel flowed normally for hours. When pilots jettisoned the tanks over Germany, they separated cleanly and fell away intact.

Every single tank worked.

Huff read the after-action reports twice, then once more, searching for anomalies.

There were none.

The concept was proven.

Now came the real challenge: scale.

By spring 1944, the Eighth Air Force operated sixteen fighter groups. Each group fielded seventy-two aircraft. Each aircraft required two tanks per mission.

The math was unforgiving.

Over thirteen thousand tanks per week.

Nearly sixty thousand per month.

Bowater-Lloyds could not meet that demand alone.

Huff moved the way he always had in manufacturing—fast, direct, without ceremony. He contacted paper mills across Britain. Scotland. Wales. The Midlands. He sent specifications, material requirements, bonding procedures. He did not ask for permission; he asked for production capacity.

By April, seven mills were building paper tanks.

Production jumped to four hundred per day. Then six hundred.

By May 1944, British factories delivered eight hundred paper tanks daily—enough to supply every long-range fighter in the European theater.

The tactical impact was immediate.

Before paper tanks, mission planners had choreographed escort coverage like a relay race. Spitfires covered the Channel. P-47s took over at the French border. P-38s pushed into western Germany. Then the bombers flew the last two hundred miles alone.

Every handoff created a gap.

The Luftwaffe exploited those gaps mercilessly.

Paper tanks erased the system.

One aircraft type—P-51 Mustangs—could cover the entire mission profile. No handoffs. No gaps. One continuous umbrella from England to target and back. Eight hours. Eleven hundred miles.

The Luftwaffe lost its sanctuary.

German fighter pilots had trained for years around a simple truth: the escorts always ran out of fuel. They waited. They conserved strength. They attacked when the bombers were alone.

Now the escorts never left.

Mustangs appeared over Nuremberg, Munich, Stuttgart, Vienna. Every interception meant facing fighters that could outclimb, outturn, and outrun German aircraft—and had the fuel to keep fighting.

By April 1944, the data was undeniable.

Missions with full escort averaged four percent losses.

Partial escort: eight percent.

No escort: fourteen percent.

The difference was paper.

The Luftwaffe tried to adapt.

They introduced rocket-armed fighters firing from long range. Heavily armored Focke-Wulf 190s pressed attacks to point-blank distance. Twin-engine destroyers bristling with 20mm cannons charged bomber boxes head-on.

It did not matter.

The Mustangs stayed.

By late May, German day fighter strength collapsed. Four hundred seventy-two pilots lost in April. Three hundred ninety-one in May. Veteran leaders died faster than replacements could be trained. Formation discipline broke down. Attacks came in pairs, then singles—easy prey for American fighters operating in coordinated groups.

Bomber crews noticed immediately.

Missions that had felt like death sentences months earlier became survivable. Flak still killed. Weather still scattered formations. Mechanical failure still forced aborts.

But the massed fighter swarms of 1943 were gone.

The skies over Germany were changing hands.

Huff watched the numbers, not the headlines.

By May, his program had cost less than one hundred twenty thousand dollars to develop and produce forty-seven thousand tanks. Analysts estimated the reduced loss rates had already saved eight hundred bombers—eight thousand aircrew lives.

The math was brutal.

And undeniable.

Yet one question remained.

What would happen when the enemy started shooting at the tanks themselves?

PART III: SHOOT THE TANKS

The Luftwaffe did not need long to understand what had changed.

German intelligence officers were methodical. They tracked American tactics with obsessive precision, comparing sortie reports, loss rates, interception timings. By late May 1944, the conclusion was unavoidable: American fighters were no longer turning back. The bombers were no longer exposed. The escorts were staying—and something under their wings was making it possible.

Captured gun camera footage showed it clearly.

Brown shapes. Cylindrical. Not metal.

Paper.

To German pilots, the discovery was baffling and infuriating. Paper had no place in combat aviation. It was flammable. Fragile. Absurd. The immediate assumption was that the Americans were desperate, improvising because they lacked proper materials.

The Luftwaffe response was predictable.

Shoot the tanks.

Captured briefing notes from June 1944 laid out the plan in blunt terms. Pilots were instructed to aim for the external fuel tanks first. Ignite them. Force the Mustangs to jettison early. Reduce their range. Drive them away from the bombers before the decisive phase of the mission.

In theory, it should have worked.

In practice, it failed—almost completely.

The first reports came back confused.

Pilots claimed they had hit the tanks. Tracer rounds punched clean holes through the brown shells. Incendiary rounds passed straight through. But there were no fireballs. No explosions. No burning fighters spiraling down.

Some tanks leaked slightly.

Most did not.

The craft paper absorbed fuel and swelled microscopically, sealing punctures through capillary action. The laminated structure prevented tearing. The resorcinol glue held. Even when hit multiple times, the tanks continued feeding fuel.

Pilots landed with tanks riddled by holes—five, six, sometimes more—having lost only a few gallons.

When tanks did catch fire, the result was even more infuriating.

Mustang pilots felt the vibration, saw the smoke, and flipped two switches. Explosive bolts fired. The tank fell away in less than two seconds. By the time flames fully developed, the burning mass was thousands of feet below the aircraft, tumbling toward the ground.

No P-51 was lost to a paper tank fire in the first six months of operations.

Metal tanks told a different story.

When damaged, metal tanks often deformed. Release mechanisms jammed. Pilots had to nurse burning or leaking tanks back to base or attempt emergency landings with unbalanced loads. Several P-47s were lost that way—crashing short of the runway, victims not of enemy fire but of equipment that could not be discarded safely.

Paper tanks always released.

They were designed to die.

By July 1944, the numbers were staggering.

Ninety-three thousand paper tanks used.

Seventeen failures.

A failure rate of 0.018 percent.

All seventeen traced to a single production batch from one factory.

Huff shut that line down immediately.

He inspected every tank from that facility personally. The entire lot was rejected and destroyed. The factory corrected its quality control process within a week. No further failures occurred.

For Huff, quality was not negotiable.

He visited Bowater-Lloyds weekly. He walked factory floors. He pulled random samples and tested them to destruction. Every thousandth tank was filled with water and pressurized until it burst. The average failure pressure was eighty pounds per square inch—three times the operational requirement.

The safety margin was enormous.

By then, the program was expanding beyond fighters.

B-24 Liberator bombers began using paper ferry tanks for long-range repositioning flights. Transport aircraft carried them on supply runs. Even some B-17s experimented with paper tanks for ultra-long-range missions into Poland and Czechoslovakia.

The design proved universal.

In June 1944, German forces captured an intact paper tank when a P-51 jettisoned both tanks over France and one landed in a field without rupturing. Wehrmacht technical intelligence examined it thoroughly.

Their report expressed disbelief.

They concluded the Americans must be so starved for metal that they had resorted to desperate improvisation.

They missed the point entirely.

Huff had not chosen paper because metal was scarce.

He had chosen paper because it was better.

By August 1944, British factories had produced 147,000 paper tanks at a total cost of just over one million dollars. Equivalent metal tanks would have cost more than nine million. The savings were immediate and cumulative.

Huff received three promotion recommendations that year.

He declined all of them.

He did not want a desk in Washington. He did not want to brief committees or manage programs from behind a stack of papers. He wanted to stay with his air technical section—testing equipment, flying aircraft, solving problems that killed men if left unsolved.

His superiors let him.

His next assignment focused on gunsights. American pilots were missing too many deflection shots. German fighters were slipping through formations because aiming systems could not keep up with closing speeds. Another team took that project.

Huff stayed with drop tanks.

Even as Allied armies advanced across France, range still mattered. Targets moved east, not west. Synthetic oil plants, ball bearing factories, aircraft assembly lines—every one of them required fighters that could stay airborne for six to eight hours.

Paper tanks made that possible.

The statistics told the story.

August 1944:

7,200 bomber sorties.

Loss rate: 1.4 percent.

October 1943:

9.1 percent.

Bomber crews knew exactly why.

They watched the Mustangs form up over the North Sea and stay with them all the way in. They saw fighters circling during bomb runs, driving off attackers, escorting damaged stragglers home.

Men who had expected to die now expected to survive.

The psychological shift was as important as the tactical one.

The Luftwaffe tried one last adaptation—mass attacks, throwing a hundred fighters at a single bomber group, accepting heavy losses to break through. Occasionally, it worked. But each success cost them irreplaceable pilots.

And the Mustangs had fuel.

They chased retreating fighters fifty miles. They fought without glancing at gauges every minute. They owned the air because they could afford to stay.

By September 1944, factories had delivered two hundred thousand paper drop tanks.

Every American fighter group in England, Italy, and the Pacific used them.

The total failure rate across all theaters: 0.02 percent.

The Pacific embraced them with enthusiasm. P-51s escorting B-29s over Japan could not fly without external fuel. Metal tanks were scarcer there than in Europe. Paper tanks solved the problem in heat and humidity as easily as they had in cold.

Huff visited Saipan in October 1944.

He expected mold. Delamination. Resin breakdown.

He found none.

The tanks loaded, flew, fed fuel, and dropped exactly as designed.

By then, the outcome of the air war was no longer in doubt.

Air superiority had been won not by a single aircraft or ace—but by range.

And range had been bought with paper.

PART IV: THE QUIET CENTER

Huff flew when he needed answers.

He did not trust charts alone. He did not trust reports filtered through layers of interpretation. When something mattered—when men’s lives depended on a system working exactly as intended—he climbed into the aircraft himself.

In March 1944, he took a P-47 Thunderbolt up on a fighter sweep over northern France. Two paper tanks hung beneath the wings, brown cylinders against the Thunderbolt’s massive bulk. The mission profile called for four hours airborne—long enough to stress fuel transfer systems, long enough to reveal leaks or feed interruptions.

The aircraft performed flawlessly.

Fuel flowed evenly. No vibration. No pressure drop. When Huff thought he spotted German fighters in the distance, he did what any pilot would do. He jettisoned the tanks.

They fell away instantly.

The Thunderbolt surged forward, lighter, faster, responsive. It was a false alarm—no enemy appeared—but the test had answered another question. The tanks behaved exactly as designed under operational stress.

In April, Huff flew again, this time in a P-51 Mustang on an escort mission to Brunswick. Six hours gate to gate. Extreme altitude. Long exposure to cold and vibration. He watched the tanks through the mirrors mounted on the canopy frame, scanning for bulging, distortion, fuel stains.

There were none.

When he landed back in England, he climbed down from the cockpit and removed the caps from the attachment points himself. Bone dry. No seepage. No residue.

From that point forward, production quality became his obsession.

Huff visited Bowater-Lloyds weekly, sometimes twice in the same week. He walked factory floors in Scotland, Wales, the Midlands. He pulled random tanks from finished pallets and cut them open on the spot. He tested glue bonds with his own hands, flexing seams until they failed—or didn’t.

Every thousandth tank was filled with water and pressurized until rupture. The average failure point held steady at eighty pounds per square inch, far beyond anything the tanks would encounter in service.

The Germans were learning, too.

Intelligence summaries in late May reported that Luftwaffe pilots had been ordered explicitly to target external fuel tanks. They understood the logic. Remove the fuel, remove the escort, expose the bombers.

But again, theory collapsed against reality.

Paper did not behave the way metal did under fire.

Tracer rounds punched holes without igniting fuel. Incendiary ammunition often passed through the laminate and exited without sustained combustion. The craft paper absorbed fuel locally, swelling and sealing around punctures. Tanks riddled with bullet holes continued feeding engines.

And when fire did occur, the tanks fell away before it could matter.

German pilots grew frustrated. After-action reports complained that Mustangs “shed burning tanks and continued fighting.” The tactic meant to cripple escorts simply made them lighter and more dangerous.

By July 1944, the numbers were beyond argument.

Ninety-three thousand paper tanks used.

Seventeen failures.

All traced to one factory.

All corrected.

The failure rate stood at 0.018 percent.

The program expanded again.

B-24 Liberators used paper ferry tanks to reposition across vast distances. Transport aircraft extended supply routes. Even B-17s experimented with paper tanks for extreme-range missions into Eastern Europe.

The design held.

In June, German engineers finally examined an intact paper tank captured in France. Their technical report betrayed disbelief bordering on irritation. The Americans, they concluded, must be improvising out of necessity—starved for metal, forced into crude solutions.

They were wrong.

Huff had not built paper tanks because metal was unavailable.

He had built them because paper solved the problem better.

By August 1944, production figures told the same story in cold numbers.

147,000 paper tanks produced.

Cost: $1.176 million.

Equivalent metal tanks: $9.261 million.

Savings: more than eight million dollars.

And cost was only part of it.

Paper tanks were expendable by design. Metal tanks were not. Metal tanks had to be conserved, retrieved, reused. Paper tanks were meant to be dropped the instant they became a liability. That single distinction reshaped air combat behavior.

Pilots no longer hesitated.

They did not nurse damaged tanks. They did not cling to fuel out of fear of losing expensive equipment. They dropped and fought.

Range gave them freedom.

Freedom changed everything.

By late summer 1944, Allied fighter bases moved onto the continent. Distances shortened for some missions—but not all. Targets in eastern Germany, Austria, and Czechoslovakia still demanded maximum range. Synthetic oil plants, ball-bearing factories, aircraft assembly lines—these were the last pillars of German war production.

Paper tanks remained essential.

Statistics from August told the story with brutal clarity.

7,200 bomber sorties.

Loss rate: 1.4 percent.

Less than a year earlier, the same force had been bleeding at over nine percent.

Bomber crews felt the difference in their bones.

They no longer scanned the sky in dread once escorts peeled away—because escorts never peeled away. Mustangs stayed overhead during bomb runs, circled stragglers, drove off lone attackers. Crews who had watched friends die over Schweinfurt and Regensburg now came home mission after mission.

The psychological shift was profound.

Men who expected death began planning futures.

The Luftwaffe tried one last time to claw back control. They concentrated fighters into massive formations—one hundred aircraft or more—accepting enormous losses to break through escort screens. Occasionally, it worked. On September 11th, near Stuttgart, a concentrated attack brought down twelve B-17s in minutes.

But such successes became rare.

The Mustangs adapted. They had fuel to counter mass attacks. They chased decoys. They pursued withdrawing fighters. They refused to be drawn away because they could afford to fight longer.

Range was no longer a constraint.

By September 1944, factories had delivered two hundred thousand paper drop tanks. Every American fighter group in England, Italy, and the Pacific had used them. The total failure rate across all theaters stood at 0.02 percent—forty tanks out of two hundred thousand.

Unmatched reliability.

The Pacific Theater embraced the tanks with particular urgency. P-51s escorting B-29 Superfortresses over Japan faced round trips of fifteen hundred miles. Metal tanks were scarcer there than in Europe. Paper tanks made those missions possible.

Huff traveled to Saipan in October 1944.

The tanks sat outdoors in heat and humidity for weeks. He expected deterioration—mold, resin breakdown, delamination.

He found none.

The tanks loaded onto Mustangs, flew escort missions to Truk and Formosa, and performed exactly as designed. When jettisoned, they separated cleanly. Tropical conditions meant nothing to laminated craft paper and glue.

Huff returned to England convinced of one thing.

The design could not be improved.

By then, the war in Europe was entering its final phase. Allied armies liberated France. Fighter bases pushed east. Some missions no longer required external tanks—but the deepest strikes still did. Berlin. Dresden. Targets beyond the reach of anything but full-range escort.

Paper tanks stayed.

The final accounting revealed what Huff’s work had enabled.

From January through December 1944, Allied fighters destroyed approximately five thousand Luftwaffe aircraft in air-to-air combat over Europe. The majority fell to P-51 Mustangs flying long-range escort missions.

Those missions would not have existed without drop tanks.

And ninety percent of those drop tanks were paper.

The chain was direct and unforgiving.

Paper tanks gave range.

Range gave time over target.

Time over target gave opportunities.

Opportunities destroyed the Luftwaffe.

Huff never claimed credit for those victories.

He built fuel tanks.

Pilots flew the missions.

Pilots pulled the triggers.

But he understood the math.

Without his tanks, the Mustangs would have turned back. The engagements would not have happened. The victories would not exist.

The numbers by war’s end were staggering.

By May 8th, 1945, British and American factories had produced 412,000 paper drop tanks.

Total program cost: $3.296 million.

Equivalent metal tanks: $25.956 million.

Savings: $22.66 million.

But the larger figure mattered more.

Analysts estimated that long-range escort missions enabled by paper tanks prevented the loss of approximately two thousand heavy bombers.

Two thousand bombers.

Twenty thousand aircrew lives.

A return on investment no other single equipment program in the war could match.

And still, Huff remained largely unknown.

PART V: WHAT PAPER SAVED

When the war ended, it did not end with fanfare for Cass Sheffield Huff.

There was no parade. No press conference. No headline announcing that craft paper and glue had changed the course of the air war over Europe. The machines went quiet, the factories slowed, and the men who had built solutions in desperation were quietly reassigned or sent home.

Huff rotated back to the United States in October 1945.

He had spent three years and four months in England. In that time, he had flown P-38s, P-47s, and P-51s. He had evaluated hundreds of modifications, rejected dozens more, and watched the air war pivot from near-collapse to dominance. Of everything he tested, nothing mattered more than the paper drop tank.

His air technical section disbanded.

The engineers scattered. The test pilots moved on. The paper mills returned to making boxes and packaging. The specialized gluing machinery was dismantled and scrapped. Within two years, not a single paper drop tank remained in military inventory.

Wright Field never apologized.

The engineers who had declared the tanks “absolutely unfeasible” simply stopped talking about them. By late 1944, Wright Field was quietly ordering paper tanks for its own test programs. The official Air Force history of World War II equipment development devoted three short paragraphs to the program—acknowledging cost savings, noting reliability, then moving on.

No mention of how close the program came to cancellation.

No mention of what would have happened if Huff had obeyed that report.

Huff did not care.

He returned to Daisy Manufacturing in Michigan and resumed his position as vice president. Eventually, he became president. For twenty-eight years, he ran a company that made BB guns. He built toys. He oversaw production lines. He worried about margins, materials, and quality control.

He never spoke publicly about his war work.

Most of his employees knew he had served. Few knew what he had actually done.

The Distinguished Flying Cross he received—for a forty-three-thousand-foot dive in a P-38 Lightning, testing the aircraft beyond all known limits—sat in a drawer at home. The citation spoke of courage, of deliberate entry into unknown regions of flight. It said nothing about paper tanks.

The paper tanks themselves vanished almost completely from public memory.

Surplus stocks were burned or buried. No museum wanted to store obsolete fuel tanks made of craft paper. No surviving examples were preserved. The innovation disappeared physically, but its influence did not.

Postwar aircraft designers took note of what Huff had proven.

Expendable components did not need to be durable.

They needed to be reliable once.

They needed to be cheap.

They needed to be easy to discard.

That philosophy shaped rocket stages, missile fairings, modern drop tanks, and disposable aerospace structures for decades to come. The concept of deliberate disposability—so obvious in hindsight—traced directly back to Huff’s paper tanks over Germany.

The pilots never forgot.

Veterans of the Eighth Air Force wrote memoirs filled with disbelief and gratitude. How could paper carry fuel at forty thousand feet? How could glued craft paper survive combat damage? How could something so cheap work so well?

The answers were never romantic.

Good materials.

Better engineering.

Relentless testing.

And the refusal to accept theory over evidence.

Colonel Cass Sheffield Huff died on September 17th, 1990.

He was eighty-five years old.

The obituaries mentioned his service in World War II. They noted his Distinguished Flying Cross. They listed his career at Daisy Manufacturing. None of them mentioned paper drop tanks. None of them connected his name to the destruction of five thousand German aircraft. None of them connected him to the twenty thousand aircrew who came home instead of dying over Germany.

But the mathematics remained.

412,000 paper tanks produced.

$3.3 million spent.

$22.6 million saved in manufacturing costs.

$400 million saved in prevented bomber losses.

Approximately 20,000 lives preserved.

No single modification program in the war achieved comparable results at comparable cost.

Huff had seen a problem everyone else considered unsolvable.

He had found a solution everyone else considered impossible.

And he had proven it with craft paper and glue.

The experts had been right in theory.

Paper should not hold fuel.

Paper should not survive altitude.

Paper should not endure combat damage.

But Huff had never asked whether paper should work.

He asked whether it could.

And then he built four hundred twelve thousand answers that said yes.

THE END

News

(CH1) 20-Year-Old Hellcat Rookie Misjudged His Dive And Stumbled Into a Strike Pattern That Dropped 3 Zero

Story Title: Eleven Seconds Over Leyte PART I: THE DIVE The altimeter spins backward. It is not supposed to do…

(Ch1) Japanese Women POWs Arrived On American Soil —And Were Shocked To See How Advanced The US Really Was

They Were Brought to America as Prisoners. What They Discovered There Broke an Empire Without Firing a Shot. Oakland, California…

(Ch1) Japanese POW Women Hid Their Pregnant Friend in Terror — U.S. Doctors Promised to Protect the Child

They Hid Her in the Dark. What the Americans Did Next Terrified Them More Than Any Weapon. WISCONSIN, 1945 —…

(CH1) “He Took a Bullet for Me!” — Japanese POW Woman WATCHED in Horror as Her American Guard Saved Her

THE LIE SHE CARRIED ACROSS THE OCEAN Akiko Tanaka arrived in the Arizona desert already condemned—at least in her own…

(CH1) “Don’t Touch Her, She’s Dying!” — Japanese POW Women Shielded Their Friend Until the U.S. Medics

SAN FRANCISCO HARBOR — WINTER 1945 Sachiko’s hand was on Hana’s shoulder the way it had been for weeks—steady pressure,…

(Ch1) “They Will Cut My Hand Off!” — German POW Woman Wept When American Surgeon Spent 4 Hours Saving

WESTERN GERMANY — APRIL 1945 They told her the Americans would cut off her hand. Not might. Not maybe. They…

End of content

No more pages to load