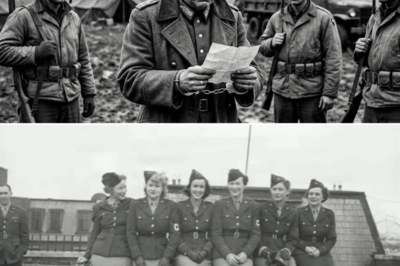

By the winter of 1944, the war had shrunk the world down to barbed wire and fear.

Somewhere in the Pacific, on an island whose name the women barely knew in English, a group of Japanese nurses and auxiliaries stood at the edge of an American prison camp. They had been pulled here from captured field hospitals and bombed communications posts, marched at gunpoint through jungle and coral dust, minds echoing with the same words they’d heard since their first day in uniform:

Never surrender. If you are captured, you are no longer human. The enemy will starve you, torture you, defile you. Better to die as a loyal subject of the Emperor.

For most of them, surrender had not been a choice at all. They had been buried in collapsed aid stations, found half-conscious in caves, dragged away from burning field hospitals. The shame of survival sat in their stomachs like a stone. Now, as the camp gate clanked open, that same stomach turned to ice.

They expected blows as they passed through the entrance.

They expected spit, slurs, hands tearing at their clothing.

What they found instead was order.

Barbed wire ringed the perimeter; watchtowers stared down with their dark silhouettes and rifles. But inside the fence, the ground was raked, the paths were clear, and the buildings were laid out in straight lines. Signboards in English and Japanese marked the infirmary, the mess hall, the barracks. Very quickly, one other detail pushed itself to the front of their perceptions.

American women.

Uniformed women moved through the compound—nurses in white armbands, clerks with stacks of papers, administrators with clipboards. They wore pants and boots, spoke briskly with male officers, and gave instructions that men obeyed. It was such an inversion of everything the prisoners had been raised to expect that many of them simply stared.

“I had never seen a woman stand next to a man in uniform and not be behind him,” one former prisoner wrote decades later. “Here, they walked beside. Sometimes in front.”

The intake process began.

It looked, at first, like any machinery of control. Lines formed. Numbers were taken. Possessions were inventoried. The women, their uniforms stiff with sweat and salt, were made to strip so that lice-infested clothing could be taken away for burning or fumigation.

They braced for humiliation.

Instead, American nurses handed them robes and moved the line efficiently toward a delousing station. Lice powder stung scalps and armpits. Hair was cut short on some, but not shorn off as a mark of disgrace. The women were pushed, certainly, but not struck. A medic—an enlisted man with dark circles under his eyes—carefully unwrapped the bandage on one nurse’s arm, grimaced at the angry red wound beneath, and began to clean it with practiced gentleness.

She watched his hands. Rough but careful. Nothing in them of the gleeful cruelty she’d been told to expect.

He caught her look.

“Honto ni, daijōbu,” he said in clumsy Japanese. “Really, it’s all right.”

He taped fresh gauze into place and moved on to the next patient.

They were shown to their barracks. The building was simple: wooden walls, a potbelly stove at one end, double bunks down each side. But there were mattresses—thin, yes, but mattresses—and wool blankets folded at the foot of each bed.

“For the first night, I slept with blankets heavier than any I’d seen since the war began,” one woman remembered. “I cried, but not where anyone could see.”

In the camp’s administrative office, the entire process was entered into Ink on forms stamped and filed. Prisoner of War. Female Section. Quarters B-3.

To the Americans, this was routine.

To the women, it was disorienting.

The next morning, a whistle shrilled through the cold air.

Roll call.

The women shuffled out of their barracks in the predawn gloom, tin cups in hand, shoulders hunched against a wind that felt sharp even after the damp heat of the islands. They lined up automatically—some habits overcome borders. They waited for the shouted insults, the rifle butts slamming into backs for being too slow.

The sergeant in charge—an American with a Kansan drawl—checked the list, counted faces, nodded.

“Mess hall,” he said. “Go.”

The mess hall smelled like every canteen they’d ever passed as civilians on the way to school: metal, steam, and food. Real food. The women pressed forward, clutching their trays with fingers that shook.

In the last year on Okinawa and in the Philippines, most of them had learned to live on a kind of hunger that never left. A bowl of thin rice gruel. A slice of sweet potato. On rare days, a scrap of dried fish the size of a matchbox. Meat had become a fairy-tale memory. Sweets belonged to another lifetime.

Now, behind the serving line, American cooks in stained aprons stood with ladles and spatulas. They slid hamburgers, mashed potatoes, soft bread, and even fruit onto the prisoners’ trays. Milk splashed into metal cups. Coffee—the real, smoky American kind—poured into others.

One woman, a nurse who’d patched men together under bombardment in Manila, stared at the plate as if it might disappear before she sat down. She took one bite and began to laugh—a quick, sharp sound that turned into a sob. The woman beside her put down her own fork and reached for her hand.

“Stop,” she hissed. “Do you want them to see you?”

But others were no better. Some giggled uncontrollably. Others sat almost rigid, eating slowly, as if every mouthful might be the last. A few simply stared at the food, unable to process how quickly the world could shift from gnawing hunger to greasy, overwhelming fullness.

“It tasted wrong and right at the same time,” one prisoner wrote later. “My mouth rejoiced. My heart hurt.”

The routine extended beyond food.

Doctors and medics did daily checks at first, then weekly. Body weight was logged. Temperatures were taken. Vitamins—small, chalky pills the women had never seen—were distributed to fight malnutrition. Nursing staff kept a special eye on wounds that had been neglected in the field.

And always, there was the barbed wire.

No one pretended this was benevolence for its own sake. The women were prisoners. The guards carried rifles and knew how to use them. Escape attempts were punished, though more often with reduced privileges and confinement than the brutal reprisals the women feared. Rules were posted. Order was maintained.

But the women could not avoid seeing something fundamental: in this place, even as the enemy, they were being treated according to rules that seemed to apply whether or not anyone was watching.

Separate quarters for women. Limited searches of private areas. Curtains drawn during medical examinations. Care given as if their lives had value.

It bored itself into them.

Within weeks, supervised letter-writing sessions were allowed.

The first letters home were tentative, written in small, careful characters, half to be understood by censoring eyes, half to try and describe the indescribable. Those who could wrote to parents in Hokkaido, Tokyo, Hiroshima, Osaka. Others had no idea where their families were, only a last known address months out of date.

One nurse who had been captured on Okinawa wrote:

“Mother, I am ashamed to say these things, but you must know. The enemy cares for us. I eat eggs, meat, and vegetables. I have a mattress and two blankets. They treat my wounds and give us music to listen to at night. The guards know our names and say good morning. I do not know how to make this seem proper in my own mind.”

Her words, smuggled through the Red Cross and past the censor’s blue pencil, would land on a kitchen table in a house with no roof, read under a candle stub.

She never knew exactly how her mother reacted.

What she did know was that when she closed her eyes at night, under the weight of those American blankets, the heat of guilt radiated more fiercely than the small stove in the corner.

“How can I swallow this food,” another woman wrote in her diary, “when I see my brothers in my mind eating roots?”

Work became part of the rhythm.

Every camp had tasks. Snow must be shoveled. Kitchens must be cleaned. Laundry washed. Gardens tended. Roads cleared. The women were assigned to details under guard—sometimes doing jobs traditionally coded as “female” back home, sometimes not.

They watched American women drive trucks, operate generators, write reports, and run supply rooms. A female sergeant in charge of the infirmary checked inventory with a pen stuck behind her ear and issued orders men obeyed without hesitation.

In the islands and cities they had come from, nurses were often expected to serve, not lead. Here, their status seemed to rise with their competence.

“If she said a thing,” one former prisoner recalled of an American lieutenant in the camp hospital, “the men did it. No one laughed. No one said she should be in the kitchen. I had never seen that before. Not once in my life.”

The prisoners were paid a small wage in camp coupons for their work. The canteen stocked items that would have been unimaginably luxurious in wartime Japan: stationery, soap, salted crackers, and—most extraordinary of all—chocolate.

“Back home, chocolate had become medicine,” one woman said. “Reserved for the very sick or very rich. Here, I saw American boys give it away to prisoners and shrug. It broke something in me.”

English classes were offered in the evenings.

Some women attended eagerly, sensing—even if they could not yet admit it—that knowledge of the enemy’s language might one day be a bridge. Others refused, offended by the idea of putting foreign words into their mouths. Yet curiosity grew. What did “Good morning” really mean when the guard said it? What was that song on the radio about? Why did the American women laugh so loudly and without covering their teeth?

Little conversations began to happen around the edges.

A guard passed out chewing gum to a work detail. A prisoner mimed her delight and then stuck it in her mouth wrapper and all, to the laughter of everyone within sight. A correction was made: “No, no—paper off first.” For a moment, the shared amusement eclipsed the categories of “us” and “them.”

These cracks did not erase trauma. Each woman carried things that could not be washed away with soap or smoothed out with routine. Names of dead friends. Visions of burning cities. The Orders from on high that had said surrender was dishonor, and the inner voice that now insisted survival was, somehow, a greater sin.

But the contrast—between the deprivation they knew their families still faced in Japan and the mundane abundance inside the wire—grew sharper every day.

In August 1945, news came like a stone dropped into still water.

Hiroshima.

Nagasaki.

Two unfamiliar names in English, and a handful of Japanese characters on Red Cross bulletins that changed everything. Atomic. Single bombs. Cities gone. The prisoners, many of whom had family in those regions or nearby, sat on their bunk planks, reading translated fragments, trying to fit the words into their understanding of war.

Some wept openly for the first time since capture, grief and fear and helplessness pouring out in great shuddering waves. Others withdrew into a silence so deep it frightened the guards. No one celebrated in the camp. Not the Americans, who had grown closer to the prisoners than they admitted; not the women, who could only imagine the scale of annihilation.

“I feared home more than prison,” a former prisoner wrote. “I feared stepping into a wasteland where the only thing familiar would be sorrow.”

As Japan’s surrender was announced and the Pacific War formally ended, repatriation began. For the women, the weeks that followed were a swirl of medical exams, briefings, and packing. They received new uniforms and traveling clothes. On the day they boarded the ships, many wept in front of their captors for the first time.

Not out of loyalty to a fallen Empire.

Out of dread.

“I did not want to leave the fence,” one woman wrote bluntly. “Outside it was hunger and rubble and judgment. Inside it was rules, enough food, and faces I had learned to trust, a little.”

The Americans did what they could. They organized extra medical supplies for the journey. They made sure each woman carried a parcel of food. Guards who had been brusque now seemed awkwardly gentle.

“Good luck,” one said, bowing slightly in a way that approximated what he’d seen them do.

“Ganbatte,” answered a woman without thinking. Do your best.

Home was not what any of them remembered.

Ships docked at shattered ports. They stepped off into cities that looked like black-and-white photographs: girders bent, blocks leveled, streets clogged with rubble and half-starved people. Houses were gone. Parents were gone. Brothers were gone. It was not always clear who had died in air raids and who had simply vanished into the maws of distant battlefields.

For many, the comforts of captivity became a kind of burden.

“You lived while others died,” neighbors hissed at one former nurse when they learned she had been a prisoner in America and not on the front when the war ended. “You were eating enemy food while we boiled roots.”

She began to duck their eyes when she walked past.

Few of the women spoke openly about the details of their time in American camps. Some said “I was in a camp” and left it at that. Others hinted at “decent treatment” and “enough to eat,” and saw expressions pinch shut on the faces of their listeners.

Honor was still a powerful word. So was shame.

“We had been taught that for a woman to be captured was shame,” one wrote. “But we had not been taught how to live afterward if capture brought kindness.”

Instead of telling their stories, many poured what they had learned into actions.

They went into nursing, teaching, social work. They supported efforts to expand girls’ education. A quiet few argued that democracy and the rule of law, ideas the Americans had talked about so often, were not foreign poison, but closer to what Japan claimed to value before militarism consumed it.

“What I learned from the American women,” one former prisoner wrote, “was not that they were better people. It was that a woman could stand in front of a room, give orders, and expect to be obeyed. I tried to remember that when I took up my work again.”

Some kept small tokens—a Red Cross booklet, a scrap of PX chocolate wrapper, a photograph of a barracks christmas—hidden in drawers. They did not show these to their children, but they took them out in lonely hours to remind themselves that the world was not as narrow as their childhood had been.

The memories of kindness in captivity did not erase the horror of war or the bitterness of loss. They sat alongside them, complicating every simple story, every attempt to paint one side all black and the other all white.

“Kindness burns longer than cruelty,” one woman wrote in her old age. “A slap I can explain away. A warm meal in the hands of an enemy—I cannot.”

It took decades for historians to ask the right questions.

When they did, when oral history projects and declassified Red Cross records began to bring these women’s voices into the light, a pattern emerged. Again and again, they described the moment they stepped through the gate of an American camp expecting degradation and found instead a system of rules that protected them. They talked of bewilderment, then guilt, then a kind of hard, sobering gratitude.

They had gone to war convinced that their enemies were monsters.

They came home wrestling with the knowledge that, for a brief and critical time, those enemies had treated them better than their own country had treated many of its citizens.

The war had ended in surrender and rubble. In its aftermath, these women carried a strange, potent knowledge: that mercy could wound as deeply as a blow, and that sometimes the most powerful act in a conflict isn’t the bullet that kills, but the hand that offers a blanket.

“I hated being a prisoner,” one of them said shortly before her death. “I hated the wire, the waiting, the shame. But I thank those Americans. Not because they fed me. Because they proved I could be seen as more than a tool to be used and thrown away. They proved I could be something more than a victim.”

Her country had taught her how to die for it.

Her captors, in their flawed, ordinary, procedural way, had taught her something far harder:

How to live afterward—and how to insist, however quietly, that dignity belonged to everyone, even the defeated.

News

(CH1) FORGOTTEN LEGEND: The Untold Truth About Chesty Puller — America’s Most Decorated Marine, Silenced by History Books and Erased From the Spotlight He Earned in Blood 🇺🇸🔥 He earned five Navy Crosses, led men through fire, and left enemies whispering his name — yet most Americans barely know who Chesty Puller really was. Why has the full story of this battlefield titan — his brutal tactics, unmatched loyalty, and unapologetic grit — been buried beneath polite military history? What really happened behind closed doors during the fiercest battles of WWII and Korea? And why has one of the Marine Corps’ most legendary figures been all but erased from modern memory? 👇 Full battle record, unfiltered quotes, and the shocking reason historians say his legacy was “intentionally softened” — in the comments.

Throughout the history of the United States Marine Corps, certain names rise repeatedly from battlefields and barracks lore. Many belong…

(CH1) A 19 Year Old German POW Returned 60 Years Later to Thank His American Guard

In the last days of the war, when Germany was nothing but smoke and road dust, a nineteen-year-old named Lukas…

Woman POW Japanese Expected Death — But the Americans Gave Her Shelter

By January 1945, Luzon was on fire. American artillery thudded across the hills. Night skies flickered with tracer fire. Villages…

Japanese ”Comfort Girl” POWs Braced for Execution — Americans Brought Them Hamburgers Instead

By the last year of the Pacific War, the world those women knew had shrunk to jungle, hunger, and orders…

6 months dirty. Americans gave POWs soap & water. What happened next?

On March 18th, 1945, when the transport train finally shrieked to a halt outside Camp Gordon, Georgia, Greta Hoffmann pressed…

(Ch1) Former Goebbels Officer Expects Torture in US Prison Camp—What He Gets Instead Breaks Him Completely

When the headline caught his eye, Eric Müller thought at first he had misread it. “President criticized for policy failures.”…

End of content

No more pages to load