Throughout the history of the United States Marine Corps, certain names rise repeatedly from battlefields and barracks lore. Many belong to Medal of Honor recipients or former Commandants. Yet one name stands apart, known even to people who have never worn a uniform: Lewis Burwell “Chesty” Puller.

Puller never received the Medal of Honor. He did not graduate from a prestigious academy, did not hold a university degree, and did not have the polished résumé expected of senior officers. And yet he became the most decorated Marine of his era, earning five Navy Crosses, one Distinguished Service Cross, and a rack of other decorations that marked him as something rare even in a hard-fighting service.

His fame did not come from a single dramatic moment. It came from something much more difficult: decades of front-line service, across three major conflicts, and an unwavering willingness to lead from the front.

This is the story of how a boy from a small Virginia town became the legendary “Chesty” Puller.

A Tough Childhood in Tidewater Virginia

Lewis Burwell Puller was born on June 26, 1898, in West Point, Virginia, a small community at the confluence of rivers in the Tidewater region. He was the third of four children born to Matthew and Martha Puller. His family had deep roots in the region; their ancestors had arrived from England in the early 1600s. Through distant branches of the family tree, he was related to another famous American officer, General George S. Patton.

Whatever comfort that long heritage might suggest did not last. In 1908, when Lewis was only ten, his father died. The family’s circumstances changed overnight. Money was tight, and the young boy had to grow up fast.

He stayed in school but also worked to help his mother keep the family afloat. He sold crabs at the local waterfront amusement park and labored in a pulp mill—hard, dirty work for a child. Those years gave him an early lesson in responsibility and endurance. The military, with its promise of steady pay and a chance to prove himself, seemed an obvious path.

Restless for War

By his mid-teens, Puller was captivated by stories of soldiers on the move. In 1916, he wanted to join the Army to take part in the Punitive Expedition into Mexico, aimed at hunting down Pancho Villa. He was underage, however, and his mother refused to sign the enlistment papers. The answer was no.

When the United States entered World War I in 1917, Puller was 17. He secured an appointment to the Virginia Military Institute (VMI) as a state cadet. This arrangement gave him financial assistance in exchange for later service. At VMI he was not a standout student; he was, by most accounts, average in the classroom. But his mind was not on textbooks. Reports of fighting in Europe constantly tugged at his attention.

He followed news of the Marines closely. The exploits of the 5th and 6th Marine Regiments, especially at Belleau Wood, made a deep impression on him. The idea of Marines as hard-hitting shock troops resonated with his own desire for action.

In August 1918, with the war still raging, Puller left VMI and enlisted in the Marine Corps as a private. He completed boot camp at Parris Island, South Carolina, and his prior time at VMI helped him win a slot at Officer Candidate School in Quantico, Virginia. After passing the course, he was commissioned as a reserve second lieutenant on June 16, 1919—just as the war had ended.

His timing could not have been worse.

Losing His Commission and Starting Over

Like all services after the armistice, the Marine Corps shrank dramatically. Postwar reductions cut the force from tens of thousands of men to a much smaller peacetime establishment. Amid this drawdown, Puller was placed on inactive status just ten days after receiving his commission. He lost his status as an officer and reverted to the enlisted ranks.

For many, that would have been the end of the story. Puller, however, refused to walk away. On June 30, 1919, he reenlisted in the Marine Corps, this time as a corporal.

His next posting took him far from Virginia, into the complex world of America’s so‑called “small wars.”

Learning the Hard Way: Haiti and Nicaragua

Puller was sent to Haiti, where the United States maintained a presence under a treaty with the Haitian government. He served in the Gendarmerie d’Haïti, a paramilitary constabulary led by American officers—many of them Marines—and staffed largely by Haitian enlisted personnel. Puller held the local rank of brevet lieutenant and quickly found himself in real combat against rebel groups known as the “Cacos.”

This was not grand, set‑piece warfare. It was patrols, ambushes, and close‑range engagements in rough terrain. Puller absorbed lessons the hard way. He used local residents as sources of information, watching how insurgents moved by night and hid by day. He began to apply these lessons in carefully planned ambushes.

In one notable action, he set an L‑shaped nighttime ambush against a rebel camp using a skirmish line to the front and machine guns on the flank. It was a textbook example of effective small-unit tactics in close terrain. Over his time in Haiti, he led more than forty operations, many of them at platoon strength. His units eliminated a significant number of rebel fighters and captured weapons, gradually wearing down organized resistance.

His performance impressed his superiors. With the support of Major Alexander Vandegrift (a future Marine Corps Commandant), Puller regained a regular commission as a second lieutenant in March 1924. Between Haiti and his later service in Nicaragua, he accumulated more field experience than any other company-grade officer of his time.

In 1928, he joined a detachment supporting the Nicaraguan National Guard in its fight against armed bands in the countryside. Once again, he was in the field more than behind a desk. For his leadership in engagements there he received his first Navy Cross—the nation’s second-highest award for valor in combat. Returning to Nicaragua after completing the Company Officers Course in 1931, he earned a second Navy Cross for his actions in a pitched battle. By the early 1930s, he was already becoming a legend among Marines who valued hard-won experience over polished manners.

China, the Classroom, and a Crucial Friendship

In early 1933, Puller joined the Marine detachment at the American Legation in Beijing, China. There he commanded the famed “Horse Marines,” a mounted unit that patrolled and guarded American interests in a region full of tension and competing armies.

Later he transferred to the heavy cruiser USS Augusta, commanding its Marine detachment. Aboard that ship he met her captain, Chester W. Nimitz—the future admiral who would command the U.S. Pacific Fleet during World War II. The professional relationship and respect built during that cruise would later prove valuable for Puller’s career.

In 1936, Puller returned home to become an instructor at The Basic School in Philadelphia. Despite his impressive record, he was denied a seat at the U.S. Army Command and General Staff College because he did not have a bachelor’s degree. Many officers might have seen that as a career-ending setback. Puller simply taught infantry tactics with the same intensity he brought to patrolling in Haiti and Nicaragua, shaping a generation of young officers.

After three years in the classroom, he returned to sea duty on the Augusta, then went ashore with the 2nd Battalion, 4th Marines in Shanghai in 1940. He had married Virginia Montague Evans in 1937, and together they would have three children: a daughter, Virginia, born in 1938, and twins Lewis Jr. and Martha, born in 1944.

In August 1941, as tensions in the Pacific deepened, Major Puller assumed command of the 1st Battalion, 7th Marines at Camp Lejeune. War was coming, and he would soon be exactly where he had always believed he belonged: leading Marines in battle.

Baptism of Fire in the Pacific

Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941 brought the United States fully into World War II. Puller trained his battalion rigorously and took it to Samoa in 1942 to help defend key positions there. Soon after, his unit was ordered to join Major General Vandegrift’s 1st Marine Division in the struggle for Guadalcanal.

Coming ashore in September 1942, Puller’s Marines were quickly thrown into the bitter fighting along the Matanikau River. During one chaotic engagement, elements of U.S. forces became trapped. Puller personally signaled the destroyer USS Monssen offshore, coordinating a daring evacuation that saved many lives. For his actions he was awarded the Bronze Star.

Later that year, in October, his battalion played a central role in the defense of Henderson Field, the vital airstrip on Guadalcanal. For three hours on the night of October 24–25, 1st Battalion, 7th Marines, alongside the U.S. Army’s 3rd Battalion, 164th Infantry, held off repeated assaults. The Americans suffered dozens of casualties but held the line. Enemy losses were far heavier.

For his calm, determined leadership under intense pressure, Puller received his third Navy Cross.

He was wounded himself on November 8, 1942, when attacks struck his command post, injuring his arm and leg. The wounds required surgery, and he temporarily relinquished command. On November 18, however, he was back with his battalion. One of his Marines during those hard days, Gunnery Sergeant John Basilone, would later receive the Medal of Honor—after Puller personally recommended him for the award.

After the Guadalcanal campaign, Puller became executive officer of the 7th Marines and took part in the Battle of Cape Gloucester in late 1943 and early 1944. There he earned a fourth Navy Cross, directing units in difficult jungle operations against entrenched forces.

Promoted to full colonel on February 1, 1944, he soon took command of the 1st Marine Regiment.

Peleliu: The Cost of a Hard Mission

In September 1944, Puller led the 1st Marines in the assault on Peleliu, one of the toughest assignments of the Pacific war. His regiment was tasked with seizing Umurbrogol Ridge, the core of a heavily fortified defensive system of caves and ridgelines.

The fighting there was brutal and prolonged. Enemy forces used well-prepared positions, overlapping fields of fire, and natural terrain to exact a terrible price. Puller’s regiment ultimately took the ridge, but at an enormous cost—over half of his men became casualties.

Some critics later argued that his style was too aggressive, even ruthless, in pressing attacks against strongly defended positions. Others noted that he led from the front, sharing the dangers of his Marines and refusing to ask of them anything he would not do himself. As with many hard-fought battles, judgments about Peleliu remained complex and often emotional.

During this period, war reached deep into his own family. In the summer of 1944, his younger brother, Samuel D. Puller, executive officer of the 4th Marine Regiment, was killed by a sniper on Guam.

With Peleliu secured, Puller returned to the United States in November 1944 to command the Infantry Training Regiment at Camp Lejeune. He remained there through the end of World War II, shaping new generations of Marines even as the global conflict drew to a close.

Back to War: Korea and Chosin

The end of World War II did not end Puller’s service. In the years that followed, he held a series of commands, including the 8th Reserve District and the Marine Barracks at Pearl Harbor.

When war broke out in Korea in 1950, Puller once again took command of the 1st Marine Regiment. Preparing his men thoroughly, he led them in General Douglas MacArthur’s bold amphibious landing at Inchon in September 1950. For his role in that operation he received the Silver Star and a second Legion of Merit.

In late November and early December 1950, as the conflict shifted dramatically with the intervention of large enemy forces, Puller and his Marines found themselves in one of the most famous actions in Corps history: the fighting around the Chosin Reservoir.

There, encircled in freezing conditions and heavily outnumbered, the 1st Marine Division fought its way out through determined resistance. Puller’s leadership during this campaign brought him the Distinguished Service Cross from the U.S. Army and a fifth Navy Cross from the Navy.

It was during this time that he delivered one of his most famous lines. When told that his Marines were surrounded, he replied:

“We’ve been looking for the enemy for some time now. We finally found him. We’re surrounded; that simplifies things.”

The remark, equal parts grim humor and unshakeable resolve, perfectly captured the way many Marines saw Puller: unflappable in the worst situations, always ready to find a way forward.

Promoted to brigadier general in January 1951, he served briefly as assistant commander of the 1st Marine Division, then as its acting commander after the transfer of Major General O.P. Smith. He returned to the United States in May 1951 and took command of the 3rd Marine Brigade at Camp Pendleton, remaining with the formation when it became the 3rd Marine Division in January 1952.

In September 1953 he was promoted to major general and, the following year, took command of the 2nd Marine Division at Camp Lejeune.

Final Years and Enduring Legacy

Years of service in tropical climates and hard conditions eventually took their toll. Puller suffered from high blood pressure and recurring bouts of malaria, which contributed to heart problems. On November 1, 1955, he was forced to retire for health reasons. He received a final promotion to lieutenant general upon retirement, a recognition of his long and distinguished service.

By that time, his list of decorations was remarkable even by Marine Corps standards. He had been awarded the Navy Cross five times and the Distinguished Service Cross once, along with two Legions of Merit, a Silver Star, a Bronze Star, and the Purple Heart, among many other honors.

As for his nickname, “Chesty,” Puller himself said he was not entirely sure where it came from. Some believed it referred to his prominent, thrust-out chest; among Marines, “chesty” was also slang for someone confident—perhaps more than a little so. Either way, the name stuck, becoming almost synonymous with the ideal of a tough, no‑nonsense Marine leader.

He retired to Virginia and lived there quietly until his death on October 11, 1971, following a series of strokes.

His family’s service did not end with him. His son, Lewis B. Puller Jr., served as a platoon leader in Vietnam, where he was severely wounded by a mine, losing both legs and parts of both hands. Despite his injuries, he built a career as a writer and advocate and was awarded the Pulitzer Prize in 1992 for his autobiography Fortunate Son: The Healing of a Vietnam Vet. He passed away in 1994.

In more recent years, the U.S. Navy honored Chesty Puller’s memory by naming an expeditionary mobile base ship USS Lewis B. Puller, the second vessel to bear his name. It serves as a floating support platform—fitting for someone whose entire career revolved around being forward, close to the action.

Why Chesty Still Matters

Chesty Puller’s life does not fit easily into a simple slogan. He was a hard man in a hard profession, praised by many and criticized by some. He could be demanding, blunt, and relentless. Yet his Marines knew he would be there with them under fire, not watching from a distant headquarters. He rose from a boy selling crabs in a small coastal town to a three‑star general, not through formal academic credentials, but through performance in the field.

He fought in the so‑called “small wars” between the world conflicts, faced jungle campaigns in the Pacific, and led men in the frozen hills of Korea. Through it all, his reputation grew not because of carefully crafted image, but because his name kept turning up wherever the fighting was hardest.

Ask a recruit today to name a legendary Marine, and odds are good you will hear the same answer echoing down the barracks:

“Chesty Puller.”

That is perhaps the strongest measure of his legacy—decades after his death, his story is still told, his quotes still repeated, and his example still used to teach new generations what it means to lead from the front.

News

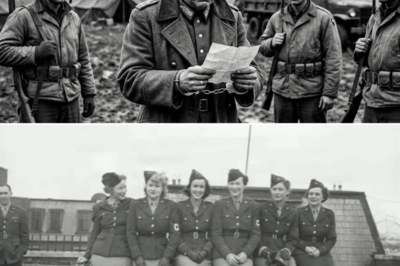

(CH1) A 19 Year Old German POW Returned 60 Years Later to Thank His American Guard

In the last days of the war, when Germany was nothing but smoke and road dust, a nineteen-year-old named Lukas…

Woman POW Japanese Expected Death — But the Americans Gave Her Shelter

By January 1945, Luzon was on fire. American artillery thudded across the hills. Night skies flickered with tracer fire. Villages…

Japanese ”Comfort Girl” POWs Braced for Execution — Americans Brought Them Hamburgers Instead

By the last year of the Pacific War, the world those women knew had shrunk to jungle, hunger, and orders…

(CH1) Female Japanese POWs Called American Prison Camps a “Paradise On Earth”

By the winter of 1944, the war had shrunk the world down to barbed wire and fear. Somewhere in the…

6 months dirty. Americans gave POWs soap & water. What happened next?

On March 18th, 1945, when the transport train finally shrieked to a halt outside Camp Gordon, Georgia, Greta Hoffmann pressed…

(Ch1) Former Goebbels Officer Expects Torture in US Prison Camp—What He Gets Instead Breaks Him Completely

When the headline caught his eye, Eric Müller thought at first he had misread it. “President criticized for policy failures.”…

End of content

No more pages to load