May 12, 1945 – Kreuzberg, Berlin

The panzerfaust was heavier than it looked in the training pamphlet.

Fifteen-year-old Klaus Becker crouched behind a heap of shattered brick and plaster, the anti-tank launcher awkward across his narrow shoulders. His hands shook – from fear, from exhaustion, from three days without real food. The Volkssturm armband they’d strapped on him two weeks earlier felt less like a badge and more like a noose.

Through dust and lingering smoke, he heard them coming.

The grinding clatter of tank treads on cobblestones. Shouts in English. The methodical advance that had pushed his “unit” – twelve boys and three old men – back, block by block, stairwell by stairwell, until there was simply nowhere left to retreat.

His Hitler Youth training whispered in his ear:

The Americans are barbarians. They kill prisoners. Better to die for the Führer than surrender to beasts.

An SS corporal – their “squad leader” – had been even more blunt before he disappeared:

“They’ll torture you and then execute you. Fight to the last bullet. Or keep one for yourself.”

Klaus had believed him. Why wouldn’t he? It was all he’d ever heard.

Now the tank rumbled closer, maybe thirty meters away. Close enough that a panzerfaust could hit it. Probably. Maybe. If he didn’t miss, if the backblast didn’t knock him senseless in the street like it had done to his fourteen-year-old friend Friedrich the day before.

Friedrich had fired, been knocked cold by the blast, and never gotten back up. The tank’s machine gun had cut him to pieces as he lay there.

Klaus’s finger found the trigger.

The panzerfaust sights trembled as he tried to line up the moving bulk of the tank. Behind the gun, he was alone with two choices he understood: die gloriously or die badly.

The tank stopped.

The turret traversed. The long barrel swung, searching, then leveled directly at his position.

Klaus closed his eyes; the expected flash and shock never came.

Instead, a voice – amplified, loud, clumsy German spoken with a harsh foreign accent:

“Komm raus, Junge. Waffen runter.”

Come out, boy. Weapons down.

Boy.

Not “enemy”, not “Nazi swine”. Boy.

He stayed frozen. This was a trick. It had to be. The minute he stood up, they would cut him down. That’s what the propaganda had said. That’s what everyone had said. The Americans killed prisoners.

But the propaganda had also promised the Wehrmacht would never retreat. That Germany was winning. That miracle weapons would turn the war. Klaus had watched whole divisions vanish, streets full of wrecked armor, comrades surrendering in groups. Berlin was burning. No secret weapons had ever come.

What if the other part of the story was a lie too?

Very slowly, Klaus set the panzerfaust down. His fingers fumbled with the sling. He stood up, knees threatening to give way, lifted his empty hands above his head.

“Nicht schießen! Don’t shoot!” he shouted, his voice cracking.

Three American soldiers stepped out from behind the tank. Rifles raised, fingers off the triggers.

They were enormous.

Klaus had been told Americans were weak, soft, addicted to chocolate and jazz. These men looked like giants. One of them was Black. Klaus’s indoctrination had been clear on that point: Black American soldiers were especially savage.

A hand clamped down on his shoulder.

Klaus flinched so hard he almost dropped to the ground, braced for the butt of a rifle or the shock of a bayonet.

The grip steadied him instead. Firm but careful, as if the man was afraid he might fall over.

When he opened his eyes, the Black soldier was holding out a metal canteen.

“Trinken,” the man said in halting German. “Drink.”

Klaus stared at the canteen. At the man’s face. There was concern there, not cruelty.

His own hands, still shaking, reached out almost without his permission. He drank.

The water was cool, clean, better than anything he’d tasted in weeks.

When he finished, the soldier took the canteen back, nodded once, and jerked his thumb toward the rear. Klaus followed the motion with his eyes.

In a shell-chewed intersection behind the tank, a loose group of German prisoners sat on the pavement under watch. Some already had field rations in their hands. No one was being beaten. No one was being shot.

“Dort,” the American said. “There.”

No torture. No execution. Just water. A nod. And directions to go sit down.

The propaganda in Klaus’s head shattered with each step he took toward the other prisoners.

Hitler Youth to Volkssturm: Children Sent to Die

Klaus Becker’s story wasn’t unique. He was one of tens of thousands of boys the collapsing Third Reich hurled into its final battles under the banner of the Volkssturm – the “People’s Storm.”

When Hitler decreed its creation on 25 September 1944, the Volkssturm was supposed to be a last-ditch national militia: all males aged 16 to 60 not already in uniform. In practice, as Germany’s situation deteriorated, those age limits dissolved. Boys as young as 12 were dragged from schools, Hitler Youth units, even homes. Some “volunteered” under the weight of years of indoctrination. Others were simply seized.

They were given armbands, castoff uniforms, a few obsolete rifles, and inexpensive single-shot anti-tank weapons like the panzerfaust. Training often lasted a matter of days.

Klaus’s unit in Kreuzberg was typical. Fifteen years old. Five years of Hitler Youth behind him: marching drills, flag ceremonies, “racial science” lectures, and cartoons depicting Allied soldiers as leering criminals.

When the Volkssturm came for him in April 1945, he’d felt a sick tangle of fear and pride. He was defending Berlin. Fighting for Germany. Serving the Führer.

Reality arrived quickly.

His unit: 12 boys, three old men. Eight rifles. Four panzerfausts. Maybe fifty rounds of ammunition between them. Their officer, a young SS corporal, made all the proper threats about cowardice and treason… and vanished within 24 hours.

“We were just children with guns,” Klaus recalled years later. “Terrified. Hungry. Waiting to die.”

Propaganda That Made Capture Worse Than Death

By the time Klaus lifted that panzerfaust in Kreuzberg, his fear of capture wasn’t a vague worry. It was doctrine.

Nazi propaganda had done its work.

From schoolbooks to newsreels, German children were fed the same message: the enemy isn’t just dangerous – he’s a monster. Radio bulletins recounted supposed Allied atrocities. Films showed American and British soldiers as sadists who tortured prisoners for sport.

Hitler Youth leaders hammered it home weekly:

Death in battle is glorious.

Retreat is shame.

Surrender is unthinkable.

Many kids believed it literally. They were told Allied soldiers skinned prisoners alive, mutilated corpses, kept body parts as trophies. One teenager captured near Würzburg remembered putting his rifle in his mouth, intending suicide, convinced that anything else was worse.

That mindset made child soldiers lethally dangerous. They weren’t fighting for ground or tactics. They were fighting to avoid what they’d been taught was a fate worse than death.

And that dogma didn’t just endanger them. It put American troops in impossible situations.

The Americans Weren’t Ready for Children With Guns

American units rolling into Germany in early 1945 expected pockets of fanatical resistance from SS veterans. They didn’t expect to be shot at by boys whose uniforms still smelled of schoolbags.

It was a moral ambush.

The rules of engagement were clear: a person with a weapon, firing at you, is a legitimate target. But that’s a cold comfort when the person behind the panzerfaust is a kid who looks like your son or little brother.

Some GIs froze. They tried warning shots, shouting in broken German, desperate to get kids to surrender. Sometimes it worked. Sometimes it didn’t.

Sometimes hesitation got Americans killed.

Sergeant Robert Mitchell of the 3rd Infantry Division remembered storming a house they’d taken fire from near Nuremberg:

“Inside were five kids. Fourteen, fifteen. Two were dead already from our fire. Three surrendered, crying. The guy next to me started crying too. He had a boy that age back home.

We’d spent months shooting at men. That day we realized we’d been shooting at children too. There was no easy way to live with that.”

Other soldiers suppressed their discomfort and fired anyway. Then spent decades trying to square military necessity with the memory of young faces in their gunsights.

Most did neither completely. They improvised.

They learned enough German to shout Ergib dich! – surrender. They held fire a second longer than doctrine advised, hoping the boy with the panzerfaust would drop it. They aimed to wound when they could.

They did what they could live with.

Mercy as Policy – Even For Child Soldiers

Once the shooting stopped, another choice began.

Captured child soldiers weren’t supposed to be a special category under the laws of war. Under the Geneva Conventions, a prisoner of war is a prisoner of war.

In practice, American units and later camp commanders made exceptions.

Teenage Volkssturm fighters like Klaus were processed and treated as POWs – but someone always noticed their age. Guards nicknamed them “kid,” “boy,” “baby Kraut”. Chaplains noted them in reports. Medics made sure they got vaccinations and extra rations.

In POW camps near Mannheim, near Nuremberg, across the American zone, administrators did small things that made big differences: keeping teens away from hardcore Nazi prisoners who might radicalize or exploit them, pushing them toward language classes and work details that taught useful skills.

Their survival rates reflected that care. Overall German POW mortality in American hands was low by the ugly standards of the time; among under-18s, it was even lower. They were fed. Treated medically. Eventually sent home.

The decisions weren’t driven by sentiment alone. There was a cold logic to it: a fifteen-year-old who survives and goes home has a lifetime to spread whatever impression he carries back with him. Better it be They treated me fairly than They murdered us.

But for boys like Klaus, the motive didn’t matter. The outcome did.

He expected torture. He got a blanket and a bowl of stew.

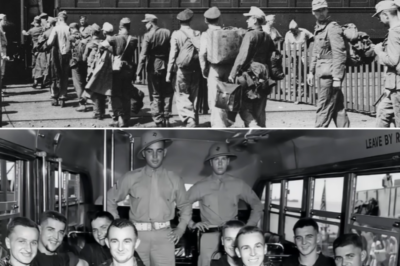

He expected execution. He got a train ride, a camp bunk, and American guards who said “Good morning” instead of pointing a pistol at his head.

“They Stopped Being Monsters”

Klaus spent seven months in an American-run transit camp.

He ate regularly for the first time in years. His body, stunted by wartime rationing, began to fill out. He learned simple English phrases from a guard who had sons his age.

“I kept waiting for the cruelty,” he said later. “For them to show their true face. It never came.”

By the time he was processed and put on a train back to a shattered Berlin, his picture of the world had been rearranged more violently than any bomb could have managed.

The city that greeted him was rubble. His father was dead. His mother was living in a basement of a half-collapsed building. Food was scarce. The Reich that had promised glory had delivered ruins.

But Klaus himself was alive.

He was alive because an American soldier – one his government had described as racially subhuman – had chosen to offer him water instead of a bullet.

He was alive because other Americans had chosen to risk their own lives not to fire too quickly on kids, had chosen to treat captured fifteen-year-olds as prisoners, not as vermin.

Years later, Klaus would say that moment in Kreuzberg did more than just save him physically.

“When that Black American soldier told me, ‘No one will hurt you,’ and I could see in his eyes he meant it, everything I’d believed collapsed.

They weren’t monsters.

We had been fighting for the monsters.”

The Chocolate That Finished the Job

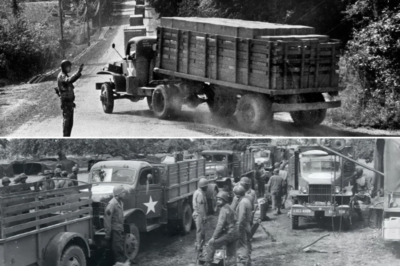

A few weeks later, in a makeshift holding area in Berlin, an American supply truck backed up to a line of seated Volkssturm prisoners. Boys in threadbare uniforms, some still wearing Hitler Youth belt buckles.

The same soldier who’d handed Klaus water appeared again, this time with a crate.

He pried it open. Chocolate bars. Hershey’s, stamped in neat raised letters.

He moved down the line, pressing one into each dirty hand.

“For you. Gute Kinder,” he said in broken German. Good kids.

Klaus turned the bar over in his fingers. The last time he’d tasted chocolate, he’d been nine and the world had still made sense.

Around him, some boys were already eating, stuffing the chocolate into their mouths with desperate urgency. Others just stared, suspicious and confused.

Klaus bit off a corner. Sugar and cocoa and fat exploded across his tongue. Sweetness and shame.

His eyes filled with tears.

Not because he was afraid. Not because he was hungry. But because the meaning of that chocolate bar was something his fifteen-year-old mind could barely comprehend.

The enemy had given him life. Now the enemy was giving him candy.

“The war is over,” the American said quietly. “You get to be kids again.”

Klaus believed him.

For the first time in years, he could imagine a future that wasn’t measured in days remaining. He went home to rubble, guilt, and the task of rebuilding a life – but he went home.

And for the rest of his life, he carried the memory of a canteen and a chocolate bar offered by men he had been taught to fear more than death.

Klaus Becker’s story doesn’t erase the horrors of that war. It doesn’t excuse the firestorms, the camps, or the many places where mercy failed.

But it does show something worth remembering.

In a burned-out street in Kreuzberg, one soldier made a choice. So did a thousand others like him in fields, camps, and ruined towns across Europe.

They chose to treat a child with terror in his eyes as a boy, not as a symbol.

They chose to put down revenge and pick up a canteen.

Those choices didn’t change the outcome of the war.

They changed what came after.

News

(CH1) When Luftwaffe Aces First Faced the P-51 Mustang

On the morning of January 11th, 1944, the sky over central Germany looked like it was being erased. From his…

(CH1) German Pilots Laughed at the P-51 Mustangs, Until It Shot Down 5,000 German Planes

By the time the second engine died, the sky looked like it was tearing apart. The B-17 bucked and shuddered…

(CH1) October 14, 1943: The Day German Pilots Saw 1,000 American Bombers — And Knew They’d Lost

The sky above central Germany looked like broken glass. Oberleutnant Naunt Heinz had seen plenty of contrails in three years…

(CH1) German Generals Laughed At U.S. Logistics, Until The Red Ball Express Fueled Patton’s Blitz

The first thing Generaloberst Alfred Jodl noticed was that the numbers, for once, were comforting. For weeks now, the war…

(CH1) German Teen Walks 200 Miles for Help — What He Carried Shocked the Americans

The first thing Klaus Müller remembered about that October afternoon was the sound. Not the siren—that had been screaming for…

(CH1) When German POWs Reached America It Was The Most Unusual Sight For Them

June 4th, 1943 – Norfolk Naval Base, Virginia. The ship’s gangplank creaked. The air tasted like coal dust and salt….

End of content

No more pages to load