On the morning of April 17th, 1945, the Rhine looked almost peaceful.

The river caught the pale spring sun in long silver ribbons. On its western bank, American soldiers trudged through mud and rubble, boots caked, shoulders hunched beneath packs and weeks of exhaustion. Smoke curled from broken chimneys. Artillery thumped far off like a storm rolling through stone.

On the eastern side, in the shadow of a collapsed farmhouse, a group of young German women had reached the end of their courage.

They were nurses, signal auxiliaries, clerks. Some had followed units as camp followers when their homes were bombed out, staying close to the only structure left in their lives: the retreating Wehrmacht. Now that army was gone, dissolved into scattered pockets and surrendering columns. The women had found shelter where they could—in ruined barns, cellars, abandoned field stations—moving like ghosts with blankets, suitcases, and the last of their food.

For weeks, fear had been their only constant companion.

The stories from the east had reached them in broken fragments. Red Army soldiers storming villages, women dragged from houses, endless reprisals. Nazi propaganda, desperate and shrill in its final months, told them Americans were no better. The leaflets and radio broadcasts warned of “Anglo-American beasts,” of rape, humiliation, and murder. If you fall into enemy hands, they said, you will not live long enough to regret it.

So when the first olive-drab soldiers appeared at the edge of the field, rifles on their shoulders, the women did what they had been trained to do. They froze.

One of them—Hilde, 21, a nurse from Dortmund—clutched the handle of her small suitcase so tightly her knuckles turned white. Another, Lena, who had once been a telephone operator in Cologne, whispered a fragment of a prayer. Several had hidden morphine ampoules in their pockets. A few had agreed, in whispers the night before, that they would rather die by their own hands than be taken and defiled.

The Americans moved forward in a loose wedge, weapons at low ready, eyes scanning. They looked tired, not triumphant. They did not shout. They did not fire warning shots. They did not break into a run.

One soldier, tall and dust-covered, lowered his rifle entirely and lifted a hand, palm out. Then he did something that did not match any rumor, any frightening story from the east.

He offered water.

He walked up, slow enough for them to watch each step, unscrewed his canteen, and held it out to the nearest woman. She drew back, instinctive, expecting a trap. The soldier didn’t force it. He just nodded, pointed at the canteen, then at his mouth, as if speaking to a frightened animal.

After a long moment, she reached out and took it.

The water was cool, metallic, and tasted more of shock than anything else. No one hit her. No one grabbed her. No one laughed.

Confusion rippled down the line.

Behind the first rank of infantry, a lieutenant with a clipboard approached. He spoke to his men first, not to the women.

“Separate them from the men. Women over here. Keep rifles down unless there’s trouble. No touching. Understood?”

The instructions were matter of fact, the tone professional. The words meant nothing to the women—they understood only the gestures—but their bodies recognized something older than language: restraint.

They were guided, not dragged, into a loose group. A few instinctively tried to cling to one another, but the Americans didn’t pry them apart. They were moved away from a nearby cluster of captured German soldiers. A perimeter was established. Guards positioned. The entire scene looked less like the beginning of an atrocity and more like the opening frame of something that none of them had expected: order.

Months earlier, the same women had lived inside a different rhythm.

The Third Reich had been built upon certainty. The slogans were painted on walls, heard in songs, repeated in classrooms. Germany was strong, self-sufficient, disciplined. Its enemies were decadent, weak, and chaotic. American society, in particular, was presented as a shabby circus of crime and corruption led by “foreign elements,” too soft and selfish to endure a modern war.

By late 1944, those slogans had become cruel jokes.

In the east, the Red Army drove westward in a relentless tide. In the west, American and British units had punched through Normandy, raced across France, and were now pouring into the heartland of Germany. Bombers shattered cities night after night. Bridges vanished in plumes of stone and water. Train stations became twisted sculptures of steel.

Supply lines flickered and died.

Once, these women had been decently fed and housed. A nurse at a Luftwaffe hospital could expect regular rations, clean bandages, and hot water. A signal auxiliary in a bunker outside Cologne might spend long, dull nights with coffee, cigarettes, and boredom. But by early 1945, “regular” meant something else entirely.

Food shrank to thin soups and crusts of dark bread. Cotton that might have gone into underwear or sanitary supplies was redirected into uniforms and gun wadding. Field hospitals ran out of gauze and began boiling old rags. Women bled into boiled sheets, traded scraps of linen in whispers, hid infections under uniforms, and pretended everything was under control.

Now, that control was gone. Army units were disintegrating, commanders dead or missing, orders contradicting each other or never arriving at all.

The only thing they still clung to was fear.

Fear of what waited across the front line. Fear of what men with guns do when no one can stop them. Fear of becoming not just defeated, but degraded.

Inside American headquarters, a very different apparatus was moving.

The U.S. Army that crossed the Rhine in 1945 had been fighting for years and had learned, sometimes the hard way, how to handle victory. Its doctrine was not improvisation. It was procedure. Regulations and routines. That included how to handle prisoners of war—male and female.

By then, the Geneva Convention of 1929 was more than a signature on a treaty. It had been integrated into training lectures, pamphlets, and field orders. Prisoners, whether taken in hedgerows in Normandy or in bombed fields in Bavaria, were to be processed, identified, separated by rank and gender, and treated humanely. Food, shelter, and medical care were not optional favors. They were written commands.

It was not mercy. It was policy.

The difference mattered little to women who had expected to die, but it mattered to the men carrying rifles that morning by the farmhouse. Their orders said: keep control, follow the rules, don’t indulge your anger.

The first hours after surrender were the worst and the most important.

The women were marched—carefully, slowly—down the rutted road toward a temporary holding point near the river. When one stumbled, an American soldier instinctively reached to help her up, then stopped himself and simply pointed, letting her choose whether to accept his hand. She did.

At a schoolyard turned processing zone, things became more structured.

A tent appeared for initial registration. Interpreters—mostly German-speaking American enlisted men and a few refugee volunteers—sat at tables with stacks of forms. Each woman was asked her name, age, unit, and role. Nurses were noted. Signal auxiliaries. Civilians who had simply latched onto retreating columns.

They were photographed. They were given numbered tags. Each step felt cold and clinical. It was dehumanizing in its own way, but not in the way they had braced for. No one spat on them. No one tore their clothes. No one asked them to do anything vile to prove their obedience.

Water stations appeared. Bread and canned meat were distributed.

The first time a loaf was thrust into her hands, Lotte—a clerk from Düsseldorf who hadn’t had a full meal in weeks—hesitated.

“Essen,” the interpreter said gently. “Food.”

She took a tentative bite. It stayed down. No one laughed when she devoured the rest.

A U.S. Army nurse examined a woman with a bandaged hand. She unwrapped the dirty cloth, cleaned the wound, and rewrapped it with sterile gauze. The German watched her movements, the professional care, the absence of contempt.

“You are a nurse?” the American asked, through the interpreter.

“Yes,” the woman answered.

“Then you know this needs to be changed again in two days.”

The German nodded, almost in disbelief.

These small exchanges, dozens of them, added up. Each one chipped away at eight years of stories and fixed images.

They were not being saved. They were being processed.

And yet, in that routine was something that felt a lot like salvation.

The camp they ended up in a few days later had once been a training barracks for German recruits. Now it wore foreign colors, but its bones were familiar: long, low buildings, gravel yards, guard towers at the corners.

The differences were in the details.

The barracks assigned to women had been cleared of men, scrubbed down, and equipped with bunks, straw mattresses, and blankets. Windows had glass. Doors had functioning latches. The latrines, while simple, had been cleaned at least once in recent memory.

The first night, many of the women slept in their clothes, clutching their belongings. Some pushed beds together in pairs. Pavlovian fear does not vanish because a uniformed stranger tells you, “You are safe now.”

But by the second and third day, something else settled in: routine.

Wake-up call at 0600. Roll call. Breakfast: bread, a smear of jam, sometimes oatmeal or a slice of sausage. Hygiene inspections. Medical checks. Work assignments: laundry, kitchen duty, cleaning. Free hours. Lights out.

Everything happened on schedule.

There was never enough—never the rich, impossible variety American soldiers enjoyed—but there was enough. Enough to stop losing weight. Enough to think in full sentences again. Enough for menstrual cycles that had stopped during the worst of the hunger to slowly return.

In their world, discipline had always come with cruelty attached. In this one, it came attached to predictable meals and clean sheets.

They watched the guards.

When a prisoner stepped out of line, she was corrected, not beaten. When an American soldier made a crude remark within earshot of an officer, he was pulled aside and read the riot act. When a woman cried out in the night from a nightmare, a nurse came, not someone to tell her to be quiet or else.

They waited for this to be a trick. For the mask to slip. For the real savagery to reveal itself.

It didn’t.

There were surely exceptions elsewhere, dark corners of a vast system where individual cruelty slipped through cracks in supervision. But for many women in camps like these, the reality remained stubbornly simple: they were taken seriously as prisoners, separated from men for their own safety, fed, kept warm, and treated as a problem to manage, not as spoils to enjoy.

The shock of that never fully went away.

“I cried,” one former nurse would later write, “not because I was hurt, but because I had been ready to die and someone gave me soup instead.”

The hardest adjustment wasn’t physical. It was moral.

These women had served a system that, in its last years, had stopped caring if its own people starved. They had watched wounded men left on stretchers because there were no trucks. They had seen civilians driven away from supply depots with nothing because “the front comes first.” They had packed and unpacked boxes of supplies that never reached the people whose names were on their forms.

Now they found themselves in an enemy camp where supplies arrived when they were supposed to. Where blankets were stacked according to a list. Where the Red Cross came to inspect and complain if rations fell below regulations.

Some of them refused to believe what they were seeing.

“This is propaganda,” they muttered to each other. “They are showing us the good side.”

But months passed. Seasons changed. The routines did not.

A few started keeping diaries again. In cramped, precise handwriting, they recorded the mundane details of captivity: the temperature in the barracks, the taste of the bread, the way the guards treated them when no one was watching.

“We were told that capture meant shame and horror,” one woman wrote. “Here, it means standing in line for soup and having a tooth filled. I do not know what to do with this.”

They felt guilt, too.

Letters from home trickled in when the postal system staggered back to life. Hamburg, Cologne, Dresden—they were ruins. Families wrote of ration cards with almost nothing listed, of children with swollen bellies, of coal shortages and nights spent huddled in coats. One woman’s mother wrote that they burned furniture for heat.

The prisoner who had just finished a bowl of American oatmeal read that line and closed her eyes, shame and gratitude wrestling in her chest.

“I ate today,” she wrote back. “I wish I could send you my ration. I cannot. I can only promise to come home strong enough to help.”

It was a cruel irony: a camp in Texas or Bavaria could, for a time, be safer and more nourishing than home.

Years later, when historians and interviewers came looking for their stories, many of the women began with the same scene.

The moment at the farmhouse or ruined village when they had expected the worst and received something else.

Not kindness, exactly. Kindness is personal. This was something more structural, less emotional, and in some ways more powerful.

They remembered the lowered rifles. The steady voices. The water canteen offered before the questions. The decision to separate them from men not to isolate them for abuse, but to protect them from it.

They remembered the shock of realizing that the enemy had rules and followed them even when no one was watching.

And tucked inside that realization was something that would change how they raised their children and how they thought about citizenship long after the war: the understanding that strength and decency are not opposites.

The Americans had had all the power. Guns, trucks, air cover, full supply lines. They could have done anything. They chose not to.

That choice, seen up close by women who had every reason to expect something else, was as destabilizing as any bombing campaign.

It did not undo the horrors elsewhere. It did not erase what had happened in the East, or in camps whose names would become shorthand for human evil. But it lodged in memory alongside those things as a stubborn counterexample.

The same species that builds gas chambers, one might say, can also build camps where captured enemy nurses get their teeth cleaned.

Both things are true. Their coexistence does not cancel one or the other. It complicates everything.

When those women stepped off trains back into a shattered Germany in late 1945 and 1946, they carried luggage and memories.

They walked through stations with no roofs and streets with no buildings and ran their fingers over ration cards that promised too little. They went looking for missing family members. Some never found them. They married or did not. They became nurses in civilian hospitals, typists in new offices, mothers in small apartments with thin walls.

In quiet moments, they told their children stories about the war.

Not just about air raids and hunger. Not just about Hitler and loss and the night the city burned.

They told them about the day they surrendered and didn’t die.

About the soldier who handed them water instead of a bullet. About the officer who said “Your war is over” and sounded like he meant it as a blessing, not a sentence. About the camp where they first learned the meaning of a foreign word that would shape their lives: rules.

Some of their children grew up to distrust all armies. Some joined new ones, under new flags, shaped by new alliances. Many visited America at least once, walking streets their mothers had only glimpsed from train windows.

They saw supermarkets bursting with goods and felt a faint echo of the shock their mothers had felt at the sight of a full American mess line. They studied health care systems and legal codes and tried to build a country where no one would need to fear the arrival of foreign rifles again.

For the Americans—the men with rifles and clipboards in 1945—the days at the Rhine and in the camps became just one part of a larger story. They went home. They married. They became teachers, mechanics, doctors, pastors. Years later, if someone happened to ask about the war, they might mention a battle, a wound, a lost friend.

If pressed, some of them would tell a softer story.

“Once,” they’d say, “we captured a group of German women. They were terrified. We treated them right.”

The listener might nod and move on, not realizing that in that understated sentence lay the crux of something enormous.

Not all victories are measured in miles gained or flags raised. Some are measured in the damage not done.

On that gray April morning by the Rhine, the war in Europe was almost over. The guns would fall silent soon. The flags would change.

But for 177 women who had rehearsed their deaths in their minds, the moment that mattered most came when five strangers in enemy uniforms chose not to become the monsters those women had been taught to see.

The war taught them that destruction could be total.

Their captors taught them that decency didn’t have to be.

News

(CH1) “SHE DON’T KNOW ANYTHING”: Greg Gutfeld Unleashes Blistering Takedown of Rep. Jasmine Crockett on Live TV — Then Drops the One Piece of Evidence That Stuns the Entire Studio Into Silence It started as a joke — and turned into a televised reckoning. During a fiery segment of Gutfeld!, the host didn’t hold back: slamming Rep. Jasmine Crockett for what he called “reckless spending, zero accountability, and nonstop noise.” But the real shock came next. Gutfeld pulled out a document linked to an alleged hidden agenda — one tied to Crockett’s recent moves in D.C. When he read it aloud, the audience froze. Even his panelists were caught off guard. 👇 What was revealed, why it matters, and how Crockett has (so far) refused to respond — full story in the comments.

She Thought One Name Would Change Everything.He Called It A New Wave.The Studio Fell Silent Before It Laughed.What Happened On…

“Just married my coworker. You’re pathetic, by the way.” I replied: “Cool.” Then I blocked her cards and changed the house locks. Next morning, police were at my door…

I never understood the phrase “blood running cold” until 2:47 a.m. on a Tuesday. It wasn’t a metaphor. It was…

(CH1) When Luftwaffe Aces First Faced the P-51 Mustang

On the morning of January 11th, 1944, the sky over central Germany looked like it was being erased. From his…

(CH1) German Pilots Laughed at the P-51 Mustangs, Until It Shot Down 5,000 German Planes

By the time the second engine died, the sky looked like it was tearing apart. The B-17 bucked and shuddered…

(CH1) October 14, 1943: The Day German Pilots Saw 1,000 American Bombers — And Knew They’d Lost

The sky above central Germany looked like broken glass. Oberleutnant Naunt Heinz had seen plenty of contrails in three years…

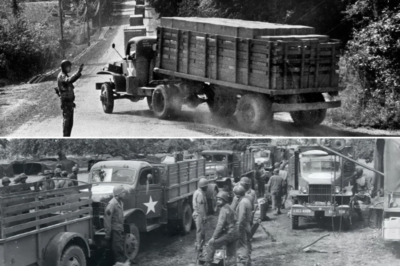

(CH1) German Generals Laughed At U.S. Logistics, Until The Red Ball Express Fueled Patton’s Blitz

The first thing Generaloberst Alfred Jodl noticed was that the numbers, for once, were comforting. For weeks now, the war…

End of content

No more pages to load