April 1945

Ansbach Airfield, Southern Germany

By late afternoon the rain had turned the concrete into a slick skin of gray. Water gathered in the bomb craters along the runway, shivering whenever another distant explosion rolled across the sky. The hangar roof over Luftnachrichtenhelferin Gertrud Seidel wasn’t really a roof anymore—just a jagged skein of twisted girders and corrugated metal. Rain leaked through in thin, steady threads. It had been doing that for weeks.

“Cable,” someone called, and Gertrud bent to haul another length of rubber-insulated wire across the floor. Her fingers, wrapped in torn cotton strips, didn’t want to close. The skin along her knuckles had split days ago. Every cold, wet handful of cable pulled the cracks open again. It hurt in a way that made her teeth ache.

She was nineteen, but she felt older. Before the war, she’d been a shoemaker’s daughter who knew how to stitch leather and balance her father’s accounts. Now she wore the gray-blue uniform of the Luftwaffe’s signals corps. The eagle and swastika had been ripped from her cuff two days earlier on an officer’s orders—“No more targets on your sleeves, girls”—but the ghost of the stitching still itched.

Around her, thirty-six other Helferinnen moved in slow, mechanical circles, hauling telephones, coiling wires, dragging field switchboards from one half-shelter to the next as units dissolved and retreated east. Their greatcoats were gone; SS men had taken them at pistol point when they’d passed through on their way to “establish new defensive lines.” Gertrud and the others had watched them go: black uniforms dry and perfect in the snow, boots polished, eyes flat.

The frostbite had followed.

It started in their fingertips, a numbness that seemed almost like relief after months of cold. Then the pain came back, sharper. Fingers swelled, split, turned mottled. They tore up shirts and old bandages to wrap their hands, but the wet seeped through. One girl, Lotte, had already lost two fingertips. The medic had burned them black with a cigarette and tied them off with a strip of gauze.

“Keep working,” he’d said. “At least you won’t feel it as much.”

That afternoon, as Gertrud dragged yet another dead weight of cable across the floor, the far end snapped free of her hands and slid through the raw meat of her palms. She gasped and dropped to her knees. Bright blood welled instantly through the filthy bandages.

“Up,” the signals officer barked, voice hoarse with sleeplessness. “We’re not done yet.”

She stood. What else was there to do?

A siren wailed once, twice—thin and ugly against the low clouds. Not the clean rise and fall of an air-raid alarm. Something closer and more animal. Two of the older men exchanged a look.

“Tanks,” one said. “Not ours.”

Outside in the rain, engines rumbled. Not the high whine of Messerschmitts or the throaty roar of the few remaining Fw 190s. These sounds were deeper. Heavier.

Gertrud stepped to the jagged mouth of the hangar and looked out.

Across the field, between the skeletal remains of other hangars and the charred carcasses of aircraft, shapes were moving through the smoke. Squat. Angular. Painted in a color she’d never seen on armor before—olive green that looked almost gentle against the wrecked concrete.

There was lettering on the side of the lead vehicle. White, large, incomprehensible at first. Then, as it drew closer and the rain wiped a smear of soot from the plating, she made it out: U.S.A. followed by a string of numbers.

Her hands forgot to hurt. Her heart did something else entirely.

“They’re here,” someone whispered behind her. It might have been Lotte. It might have been her own mouth.

American.

A dozen thoughts tumbled, chain-linked and frantic. The stories they’d heard from the Party women, from the newssheets that still arrived with less and less paper and more and more venom. Americans beat prisoners. Americans raped German women by the thousands. Americans would ship the young ones to mines in Africa, to brothels in France, to factories in Chicago where they died at their machines for capitalist bosses. Better to die now, officers had said. Better a bullet than American chains.

Her stomach clenched around nothing. There was nowhere to run. Beyond the hangar mouth the airfield yawned open, cratered and slick. Beyond that, forest and fields still dusted with old snow. And beyond those—the end of the world she knew.

“Fall in,” the officer croaked at last. His shoulders slumped as if someone had cut away the strings that had been holding him upright. “In a line. Hands visible.”

They stumbled into formation, a ragged row of gray and blue, hands held out away from bodies, bandages filthy and hanging. The men stood off to the side, fewer now than there had been a month ago. The last time a Ju 52 had come in, half the ground crew had fled aboard it. There were no more planes in the air now. Only these new machines grinding across wet concrete, their turrets low and lazy. The barrels of their guns looked bored, almost.

The lead jeep broke away and bounced toward the hangar. It slid to a stop ten meters away. A man jumped down, boots splashing in the shallow puddles.

He was shorter than she’d expected. Not a giant or a brute. His helmet rode low over his eyes. A strap of his rifle crossed his chest, but his hands were empty except for a crumpled pack of cigarettes tucked under one arm. He wore a jacket the color of new moss and trousers stained with oil and mud.

He popped a piece of something from his pocket into his mouth and chewed.

Wrigley’s, a word came from somewhere in Gertrud’s memory. Chewing gum. The thing candy-store windows used to advertise before kids like her learned to read silhouettes of planes instead of labels.

He looked at them for a long moment. There was no triumph on his face, no sneer, no hunger. Just a strange, alert tiredness, the look of a man who had been awake for a long time and expected to stay that way.

“Ladies,” he said at last.

The interpreter behind him—a lanky GI with a hooked nose and German vowels as crisp as any schoolteacher’s—repeated, “Frauen.”

The word sounded wrong in a soldier’s mouth.

A second jeep pulled up behind the first. Two men climbed out carrying wooden crates. The crates were stamped with numbers, letters, neat markings. They did not look like they contained bullets or grenades. They looked like something that should be stacked in a warehouse, tall and clean, under electric lights.

Gertrud’s heart hammered. If it’s not bullets, then—?

The sergeant jerked his chin toward the women. “Hands,” he said. He pointed to his own, then to theirs.

No one moved.

His jaw tightened in what might have been exasperation, not anger. He levered the lid off the nearest crate with the butt of his rifle.

Inside, neatly lined up like loaves in a baker’s rack, lay rows of gloves.

Heavy, leather gloves. Dark brown, almost black. The inside was lined with something pale. Fleece, or sheepskin. They were new—not cracked relics pulled from some supply depot’s forgotten back shelf. New. They still smelled of tannery and factory, of chemicals and animal hide.

For a second no one breathed.

“Gloves,” the interpreter said, a little unnecessarily. “Handschuhe. For you.”

He didn’t need to add the last words. The sergeant was already reaching in.

He picked up a pair from the crate and walked toward the front of the line. Toward Gertrud.

“Here,” he said gently.

He held the gloves out.

Her hands knew what they wanted before her brain caught up. They reached, trembling. The bandages had stuck themselves into the cracks in her skin. When her fingers brushed the leather, pain flared bright and hot. She almost hissed, almost pulled back.

The sergeant saw the flinch. Something moved in his face. He took her right wrist, slowly, deliberately, in both of his hands, making sure she could pull free if she wanted.

“Okay?” he asked, eyes meeting hers.

They were hazel, she noticed absurdly. Not blue or gray, not the cold flat color of the propaganda posters. Just human, threaded with bloodshot lines, the eyes of someone who’d seen too many things and was still trying to sort them.

She nodded once.

He unwrapped the filthy cotton strips, letting them fall wet and stained into the puddle at their feet. Her skin beneath was swollen and torn, gray at the edges of the cracks, mottled with the beginnings of infection. He sucked in a breath between his teeth. Not a theatrical sound—a reflex.

He slid the glove over her hand himself, guiding each finger into its sheath. The inside was soft. Warm, even in the cold rain.

It squeaked.

The small, ridiculous eek of new leather rubbed against itself. It was a sound she hadn’t heard in years. German gloves no longer squeaked. German anything no longer squeaked. German things creaked, cracked, crumbled.

She stared at her hand, encased in something that had come out of a crate like bread from an oven.

“Next,” the sergeant said softly.

He moved on. Behind him, the other GIs stepped up, grabbing pairs two and three at a time, dropping them into open palms, tugging them over cramped fingers, laughing when someone tried to flex too fast and winced.

Murmurs began to rise around her in German.

“Neue…”

“Richtige Handschuhe…”

“Für uns…?”

“For us,” someone whispered, sounding more offended than grateful, as if the universe had broken some rule they’d never been told about. “Real ones. Not even patched.”

Beside her, Lotte made a strangled noise as a glove slid over the hand where two fingertips were missing.

“Warm,” she gasped. “It’s warm.”

That night, Gertrud found a corner of what had once been an office—desk overturned, file cabinets gutted—and sat on the floor with her back against the damp wall. The gloves lay in her lap.

Rain pinged softly on the broken glass in the window frame. Farther off, artillery rumbled. The war was not over elsewhere, not yet, but here on this airfield it had ended with a gentle pressure on her fingers.

She pulled the gloves on again. They squeaked in the dark.

In the flicker of a small candle someone had lit from a stolen cigarette butt, she could see the stamp burned into the leather near the cuff. U.S. Army Air Forces. Contract number. A date too recent. These hadn’t been hoarded since 1939. They had been made while Germany starved.

She flexed her hands. No pain. Just pressure and the strange, foreign feeling of being protected.

“We heard they would starve us,” she wrote in the small notebook she had carried through three transfers and two retreats. She’d stolen the paper from a signals office in ’43, back when paper was still plentiful. “We were ready for that. We were ready for blows. We were ready to hide our faces. We were not ready for gloves.”

Her pencil hovered.

“I no longer understand this war.”

The gloves were not an isolated miracle. They were part of a pattern she only recognized with time.

Two days later, medics arrived with tins of white powder and small glass ampoules of sulfa drugs. They lined the women up, opened wounds, sprinkled powder, wrapped clean gauze. Hands that had been left to fend for themselves under German care were suddenly receiving treatment that would not have been out of place in 1939’s best hospitals.

“Look,” whispered Magda, the signals NCO who had once scolded them for sloppy uniform buttons. “Real bandages. Not cut-up sheets.”

Gertrud watched an American medic—Goldstein, according to the name tape—bend over Lotte’s mangled hand. He was Jewish. She could see it in the way he flinched at the sight of the Luftwaffe insignia on the wall before someone tore it down.

And yet his fingers were as gentle as the sergeant’s had been. He cradled Lotte’s wrist, cleaned her wounds, muttering softly in a language Gertrud didn’t know. Hebrew, maybe. He looked up once, caught her eye, and something passed between them that had nothing to do with rank or language.

Hurt is hurt. Hands are hands.

Afterwards, Lotte fell asleep with her gloved hand cradled against her chest.

Weeks later, in an American-run camp farther west, Gertrud saw the same crates again.

Camp Struth, they called it, a name that sounded harsh but was just the hometown of the colonel on the gate signs. The rain had stopped. The Texas sun—which the older prisoners spoke of with both fear and awe—was still a rumor. For now, it was still Germany. The fences were real. So were the guard towers.

So were the milk cans that arrived every morning.

“You are prisoners now,” the commandant had said in careful German, standing on a crate so they could all see him. He was not much older than they were. “But under the Geneva Convention you are also protected persons. You will be fed. You will be housed. You will work, but not as slaves. Anyone mistreated should report it.”

He had said the last part with a sideways glance at his own guards.

Gertrud didn’t fully understand the words. Protected person. Geneva Convention. They sounded like phrases from some other kind of war where someone drew up rules on paper and everyone followed them. Her war had been mud and steel and voices screaming in the dark.

But the food arrived.

The milk was thin, but it existed. The bread was soft enough to dent. They got meat. Maybe only twice a week, but that was twice more than she’d expected. Her father, when he’d written from Nuremberg in ’44, had spoken of a meat ration of 100 grams per week, if you could get it at all.

“It is wrong,” Lotte said once as they sat on their bunks and chewed. “Children are eating rats in Berlin, but we—”

She broke off and looked at her own piece of sausage.

Gertrud swallowed. “If we don’t eat it, they won’t send it to Berlin,” she guessed. “They’ll just throw it away.”

The thought made her skin crawl.

Months later, after Germany surrendered, after they were moved again, this time far away across an ocean to Camp Swift in Texas, the gloves came out of the box less often. The sun did their work for them. In Texas, the challenge was not keeping your fingers from freezing but keeping your brain from boiling.

But she kept them.

She kept them when they learned about the camps in the east, about places with names like Buchenwald and Dachau. She kept them when an American chaplain showed them photographs of stacked corpses and starved survivors. The images made her stomach turn.

“We didn’t know,” many of the women said. It sounded hollow, even to their own ears.

Some had known pieces. All had chosen not to ask too many questions.

She would sit on her bunk on hot nights, the gloves in her lap, and try to hold both truths at once: that her country had built those places, and that the country that had freed them had also turned cities like Dresden and Hamburg into firestorms.

Harm, harm, harm. On both sides.

And yet—there were also gloves.

She wore them again the winter she came home.

Home wasn’t home.

Nuremberg was a tangle of broken stone. Churches were shells. The building where her parents had lived was simply gone, reduced to a heap of brick and plaster. Of her family, only an aunt remained, living in two rooms with eight others and a coal stove that gave more smoke than heat.

Food was rationed. Real coffee was a fantasy. So were oranges, chocolate, decent shoes.

Her aunt eyed the gloves the first time she saw them.

“Where did you get those?” she asked sharply.

“America,” Gertrud said. She held her breath.

Her aunt snorted. “Of course. While we freeze.”

Gertrud understood the bitterness. She felt it, too, every time she walked past a queue in front of the bakery and knew that the American meals she’d eaten as a prisoner had been richer than anything her own family had seen in years.

She almost put the gloves away for good.

Then one day she saw a man on the street, fingers bare and blue, trying to light a cigarette. She took the gloves out of her pocket and put them into his hands without a word.

He blinked.

“They’re American,” she said, before he could ask.

His jaw tightened. “We don’t need—”

“You do,” she said, more sharply than she’d intended. “They owe us nothing and gave them to me. I owe you something, and I am giving them to you. Either take them or freeze.”

He took them.

She went home and sat at the small table in her aunt’s kitchen. Her hands were cold. Her nose ran. Somewhere down the street a coal wagon rattled by, the driver shouting out his meager load.

She felt lighter.

That night she wrote, “I always thought the gloves meant their abundance and our scarcity. Maybe they also mean what we do when we have a little abundance of our own again, however small.”

She didn’t keep the original pair. But later, when the Wirtschaftswunder began and West Germany’s factories hummed to life under the soft shadow of American aid, she bought new gloves every few winters. Leather, good ones. She looked for the same squeak.

She married, had two children. She worked as a bookkeeper in a small factory that made machine parts, then in a larger firm that exported to France and, eventually, to America. Sometimes she smiled at the invoices. Dollars, not Reichsmarks. Stamped with places she now knew on a map: Detroit. Cleveland. Omaha.

When her children asked about the war, she told them the whole of it.

The sirens. The fear. The guilt. The camps. The lies.

And the gloves.

“The gloves?” her son laughed the first time, thinking she’d misspoken.

“Yes,” she said. “The gloves. That was when I realized that the people we were told were savages fought just as hard as we did, but also had enough left over to be kind.”

Her daughter frowned. “Is that enough to forgive them for the bombs?”

“No,” Gertrud said. “Kindness doesn’t erase harm. But it shows what is possible. It shows what we should expect from ourselves.”

In 1985, long after her husband died, her granddaughter convinced her to attend a reunion of former Helferinnen at a small hotel in Munich. There were only a few dozen of them now. Time had done what war and famine hadn’t.

They sat in a bright conference room with bad coffee, good cake, and name tags pinned over blouses. They compared notes on hips and heart medication, on grandchildren and pensions. And eventually, the conversation turned, inevitably, to 1945.

“Do you remember the gloves?” someone asked.

Half the women in the room nodded at once.

“They squeaked,” one said. “Do you remember that?”

Laughter.

“My father cried when he saw mine,” another admitted. “He had stolen boots from a dead comrade the month before. He said, ‘They had this to spare?’”

A woman from Vienna, now living in Hamburg, shook her head. “I still have mine,” she said. “I kept them in a box all these years. When I put them on, I feel nineteen again and very stupid.”

They all knew what she meant.

That nineteen-year-old who believed she was serving the most advanced nation on earth, whose factories would never fail, whose leaders would never lie—that girl was harder to forgive than any American or Russian or British soldier.

They raised their coffee cups.

“To stupid nineteen-year-olds who can still learn,” someone said.

“To warm hands,” said another.

“And to crates,” Gertrud murmured, mostly to herself.

One November, late in her life, Gertrud took her youngest granddaughter to see an exhibit about the war at the Dokumentationszentrum in Nuremberg. Glass cases held uniforms, medals, pieces of shrapnel. Photographs lined the walls. Some showed faces she’d seen once on banners. Others showed faces like hers, small and tired in the background.

Near the end of the exhibit, in a case of objects from occupied Germany, there lay a pair of gloves. Brown leather, fleece-lined, stamped with U.S. Army.

Her granddaughter leaned closer.

“Oma,” she breathed. “Look.”

Gertrud smiled. Lines around her mouth softened. “Yes,” she said. “Those.”

“They’re just gloves,” the girl said. “Why are you smiling like that?”

“Because they’re not just gloves,” Gertrud answered. “They’re the moment I realized our leaders had built our pride out of paper, and someone else had built theirs out of machines that could make this,” she tapped the glass, “by the millions and still have enough to give away.”

“That sounds…sad,” her granddaughter said slowly.

“It was,” Gertrud agreed. “And also the beginning of something better. When you stop believing lies, even if the truth hurts, you can start building something real.”

She watched her granddaughter’s reflection in the glass, the way her brow furrowed as she tried to fit this story into the ones she’d been told in school. About the Marshall Plan. About NATO. About the European Union.

“It’s easy to talk about freedom,” Gertrud added after a moment. “Harder to remember that it includes warm hands in winter. That a country that calls itself free should be able to do both—make speeches and make gloves.”

Her granddaughter nodded slowly.

“I’ll remember,” she said.

Gertrud believed her.

The rain that had fallen on Ansbach that long-ago April still fell sometimes in her dreams. Cold. Relentless. Smelling of fuel and fear. But when she woke, her fingers would still curl in remembered leather, and she would know that somewhere, in warehouses and factories and ordinary houses, there were still crates waiting to be opened.

Someone would slide something soft and warm over someone else’s hurt skin.

Someone would choose to share when they could have turned away.

And that, she thought, was as good a definition of strength as any flag.

News

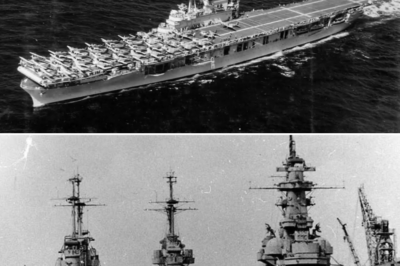

(CH1) Captured German Officers See a US Aircraft Carrier for the First Time

The first time they heard about the American carriers, most of the officers in the Kriegsmarine laughed. It was early…

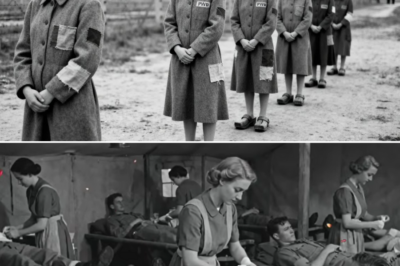

(CH1) German POW Nurses Said: “You Treat Us Well, How Can We Help?” — “Heal Our Wounded”, Said The General

When the trucks stopped at Camp Rucker, the Alabama sky looked wrong. It was too big, too blue, too indifferent…

(CH1) Captured German Nurses Were Shocked With American Medical Abundance

The first thing that hit her was the smell. Not blood, not gangrene, not the sour stench of bodies crammed…

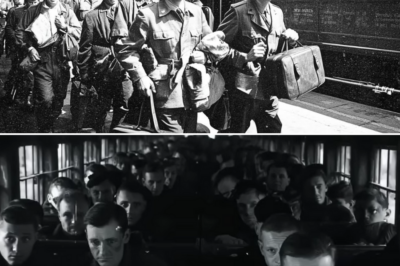

(Ch1) When German POWs Reached America They Saw The Most Unexpected Thing

The first thing that hit him was the smell. Not coal smoke or cordite or the sharp bite of disinfectant…

(Ch1) Female German POWs Didn’t Expect New Shoes—and Socks—in America

The order came in English first, then in rough, accented German. “You’ll remove your shoes now.” The voice was flat,…

(Ch1) He Taught His Grandson to Hate Americans — Then an American Saved the Boy’s Life

January 1946, the war was over, but the ground still killed. In a ruined German city, American combat engineer Paul…

End of content

No more pages to load