The first thing Klaus Müller remembered about that October afternoon was the sound.

Not the siren—that had been screaming for nearly a minute already—but the way all the other sounds in Düren seemed to hold their breath at once. Shop doors half-closed and left hanging, a cart abandoned in the middle of the street, the echo of a shouted name chopped off mid-syllable as people vanished underground.

Then the bombers came.

He heard them before he saw them, a distant vibration rolling across the slate roofs, deepening into a mechanical growl that seemed to rattle the fillings in his teeth. Klaus stopped dead in the middle of the station square, eyes turned upward. For a moment, they were only black specks against the pale autumn sky. Then they grew, resolving into the unmistakable shapes he’d seen in newspapers and propaganda films. RAF Lancasters. Dozens of them.

Someone grabbed his sleeve.

“Klaus!” It was old Frau Heinemann, her blue scarf askew. “Get underground, you stupid boy!”

Greta. The thought shot through him like an electric shock. His sister was at home. Greta, nine years old, with her one good dress and the habit of chewing her braids when she was nervous. She’d been helping their neighbor boil potatoes when he left that morning. Home. She would be home.

He tore his arm free and ran.

He’d been told, over and over, that only the weak ran. That German youth stood firm. That to flee was dishonor. Hitler Youth leaders had shouted it in his face until spit flecked their lips. But those men didn’t have a little sister with plaits and ink on her fingers from making drawings on scrap paper.

The first bombs fell as he turned into Hülstraße.

The world became noise and pressure. A blast picked him up and threw him like a rag doll. He slammed against something—wall, ground, he didn’t know—and lost all direction. For a long moment, there was nothing but ringing in his ears and a weight on his chest that made breathing an effort.

When he forced his eyes open, the sky was gone.

Dust and smoke turned the daylight into a red-brown murk. Somewhere nearby, someone was screaming, a high, endless sound that rose and fell and rose again until abruptly cut off. Flames licked at shattered wood. Roof tiles lay like broken teeth on the cobbles. The panel of a door, painted green, leaned crazily against what had once been a bakery.

Hülstraße was gone.

The neat row of apartment buildings and small shops—gone. In their place: heaped brick, splintered beams, twisted metal. Klaus didn’t think about what this meant. He couldn’t. He dug himself out from under fallen plaster, coughing, and stumbled forward, legs moving without waiting for his permission.

“Greta!” he shouted, the word torn from his throat. “Greta!”

The shape where their building had been was unrecognizable. The ground floor had collapsed inward, the upper stories pancaked on top of it. Only part of the rear wall still stood, blackened and cracked, windows blown out. Klaus scrambled up onto the rubble, hands clawing at brick and stone.

“Greta!”

He tore his fingernails bloody pulling at a chunk of masonry that had once been the lintel over their front door. It refused to move at first, then shifted with a grinding sound. He heaved, muscles screaming, and it toppled aside. Through the gap, the dark maw of the cellar.

“Greta!” he shouted again, voice breaking.

For a long moment, there was nothing. Just the roar of distant fires and the groans of collapsing beams.

Then: a cough.

“K… K-Klaus?” Faint. Choked. But there.

He sobbed, half relief, half terror. “Hold on! I’m coming!”

The cellar stairs were gone, replaced by a jumble of broken boards and bricks. He lowered himself down, scrapes of pain flaring along his shins. Dust puffed with every movement, filling his lungs. He could barely see. The emergency candle Greta had lit before the raid had tipped over, leaving wax hardened in dripping stalactites on a fallen crate.

“Here,” she whispered from the darkness. “Klaus, here.”

He found her under what had once been the old butcher’s heavy oak table, now tilted at an angle like a tent. Debris lay across the top, but the thick timber had shielded where she crouched, arms over her head, eyes too wide in her pale face.

“I knew you’d come,” she said, the strange calm of shock in her voice.

He tried to laugh. It came out as a cough. “Of course. You think I’d leave you here?”

He’d expected her to be frightened. Instead, she looked eerily detached, lips pressed tight, breath coming in little panting gasps. It wasn’t until he tried to pull her out from under the table that he understood why.

Her left leg was pinned.

A beam from the floor above—a rough, splintered joist—had driven itself between table and floor, catching her shin. At first, he thought she was stuck. He braced his feet and heaved at the wood. It didn’t move. Greta swayed, head lolling, as a choked whimper escaped between her teeth.

He looked down.

The beam had crushed her leg against the ground. The skin above her ankle bulged unnaturally around it. Below, her foot lay at an angle feet were not meant to adopt.

“Don’t,” she panted, gripping the table. “Don’t, Klaus. It… it doesn’t hurt. Much. Just get me out.”

He bit his tongue until he tasted blood. “I have to move it.”

He tried again. The beam groaned. Something down there—bone, maybe—made a soft, sickening crunch. Greta screamed then, the sound tearing through the cellar.

Eventually, with leverage from a broken chair and everything he had left in his arms, he managed to lift the beam enough to drag her free. She passed out halfway up the pile of rubble. He carried her the rest of the way, lungs burning, through a street that no longer existed as a street.

The church had become a hospital overnight.

Klaus hadn’t known how many people lived in Düren until they were all trying to fit into the same space. The pews were gone, stacked against the wall, replaced by rows of mattresses and blankets and, for those less lucky, bare floor. The air stank of blood, sweat, and something sourer that clung to the back of the throat.

The veterinarian stood near the altar.

He wore a once-white coat now stained gray with ash. His hands moved quickly, efficiently, checking wounds, tying tourniquets, palpating broken ribs. There were crude stations laid out. Wounds that might live to the left. Wounds that probably wouldn’t on the right. A boy of Greta’s age lay on two crates with a sheet over his face. His hair stuck out at the top. Klaus pretended not to see.

“Next,” the veterinarian called without looking up.

Klaus shuffled forward carrying Greta. He tried to keep her leg still. Every time it bumped, her eyes fluttered and she made that same low, animal sound.

The veterinarian glanced up, sighing. “Put her down. Gently.”

He peeled back the blanket. Examined the leg with quick clinical touches. Looked into Greta’s eyes. They slid away from him, unfocused.

“Crushed fracture,” he said flatly. “Likely damage to the tibia, maybe the fibula. Blood supply compromised. That bruise there? That’s not good.”

“What does that mean?” Klaus asked.

The veterinarian pressed his lips together. “It means gangrene will set in. That tissue is dying already. Left alone, the infection will spread. Into the blood. Into the organs. She’ll get septic. She’ll die.”

Klaus swallowed. In his mind, the word gangrene was a thing of nightmare stories. It turned limbs black. It stank. The smell in the church told him the veterinarian spoke from experience.

“You can fix it,” Klaus said. “You have to.”

“Fix?” The man let out a bitter laugh. “Boy, I have 200 wounded and three rolls of bandage. No penicilllin. No sulfa drugs. No anesthetic. I am a veterinarian who used to treat cows. I can amputate, not ‘fix.’”

“Amputate?” Klaus’s vision blurred.

“I cut off the leg.” The veterinarian’s eyes were tired, but not unkind. “If I do it now, she might live through it. If I wait, the infection will spread and then not even that will help. You decide.”

Klaus looked at Greta.

She was awake again. Listening. Understanding, because she was not stupid. Her fingers twisted in the blanket.

“No,” she whispered. “Klaus, don’t let him. Don’t let him cut it off.”

His throat closed.

“Isn’t there something else?” Klaus asked hoarsely. “Some… some medicine?”

“In Berlin, maybe. In Hamburg, before the bombs. Not here.” The veterinarian straightened. “I don’t have time. Others are waiting. Decide now or take her away.”

Klaus felt all the air leave his lungs at once.

He imagined Greta with one leg. Hopping. Falling. Being stared at. He imagined her dying. Turning gray, then green, then black.

“I… I can’t,” he said.

The veterinarian shrugged, already turning away. “Then say goodbye. I won’t ask again.”

They tried home first.

Home was a crater.

The building that had collapsed had now burned. Rain and time had already smoothed some of the sharp edges. Smoke no longer rose, but the smell lingered. Klaus carried Greta anyway, shifting her weight whenever she winced.

“Where are we going?” she asked.

“To find help.”

“There is no help. Everyone’s dead.”

He wanted to say she was wrong. He didn’t. He kept walking.

He tried the next town over. The roads were filled with refugees. People dragging carts, pushing bicycles, carrying bundles on their backs. A woman walked past them, barefoot, her shoes tied together and slung over one shoulder to save the soles.

The hospitals were full there as well. The doctors gone. The nurses exhausted. “We can’t take anyone else,” they said, glancing apologetically at Greta’s leg. “Try further west. The Americans have good hospitals. If they don’t shoot you.”

The Americans.

Until now, they had existed in Klaus’s mind only as monsters in posters. Gorillas in uniforms, teeth bared, strangling Germania. In the classroom, Herr Völkmann had described them in detail.

“The Amerikaner,” he’d said, pacing between wooden desks, boots thudding. “They pretend to be civilized, but beneath their neat uniforms they are animals. They rape, they torture, they take trophies. The miserable negro soldiers are worst of all. They know no restraint. If you are captured, you will beg for death. Better to fight to your last cartridge.”

Behind him, a poster showed a hairy fist crushing a German child.

The words had stuck deep.

At night, when the air raid sirens howled and the bombs fell, Klaus had whispered to Greta: “If the Americans come, we have to run. Never let them take you. Do you understand?”

“Yes,” she’d whispered. “I won’t let them.”

Now she was ten days into an infection that would kill her, and the only people in the world with medicine were those same Americans.

Klaus sat on the edge of the broken fountain in the center of a nameless village and made a choice.

He’d been told death was preferable to capture.

Greta’s life mattered more than principles.

“Listen,” he said, taking her hand. “I’m going to the Americans.”

Greta stared at him, eyes huge and fever-bright. “No.”

“I have to. They have medicine. You heard what the doctor said. Without it…”

He couldn’t finish.

“They’ll kill you,” she whispered. “They’ll kill you, or cut you open and… and…” She didn’t even have the words for what the posters had implied.

“Maybe,” Klaus said. The honesty surprised them both. “Maybe they will. But you will die for sure if I stay.”

She squeezed his hand so hard his fingers hurt. “I don’t want you to die.”

“I don’t want you to die either.”

For a moment, neither spoke. The sounds of the ruined town washed over them—hammering as someone tried to nail a plank over a broken window, a baby wailing thinly, a pot clanging.

Klaus reached into his pocket and took out a scrap of ration card and a pencil stub. He smoothed the paper on his knee.

“I’m going to write them a note,” he said. “In case they don’t understand me. I’ll tell them everything.”

The pencil shook in his hand.

Please help my sister. She is 9 years old. Her leg is crushed. Infection. She will die without medicine. My name is Klaus Müller. I am 14. I will do anything. Please.

He read it once. It looked thin and stupid and childish on the torn card. But it was all he had.

He folded it carefully and tucked it into his pocket.

“Stay here,” he told Greta. “Stay with Frau Heinemann. I’ll be back.”

“Do you promise?” she asked, voice breaking.

“Yes.”

It was the biggest lie he’d ever told.

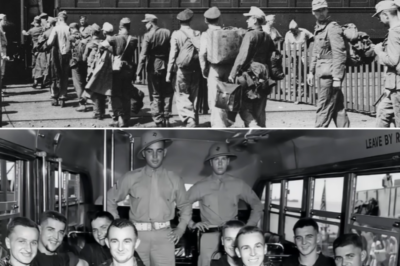

The first 20 kilometers were the hardest.

He had shoes when he left. Thin, worn, but shoes. They fell apart on day one, the soles separating like bark peeling from a tree. He kept them on until the leather flapped with every step, then tore off what remained and wrapped his feet with rags torn from his shirt.

The roads west were clogged. Refugees heading in the same direction. Soldiers heading the other way. Klaus kept his head down, blending into the gray tide.

At night, he slept in ditches or under hedges. The October air was cold enough that he woke shivering. Once he curled up behind a half-burned haystack and dreamed of Greta burning up with fever alone.

He stole a turnip from a field. It was hard and raw and tasted of dirt, but it filled the hollow ache in his stomach for an hour. He drank from streams with dead fish floating in them. Each swallow tasted like guilt.

On the third day, the coughing started.

It began as a tickle at the back of his throat. By afternoon it was a full, hacking fit. His chest burned. Every breath felt like needles. Heat flashed through his body; then he shook so hard his teeth chattered. He knew enough about sickness to recognize fever when it came.

“Not yet,” he croaked to whatever power might be listening. “Let me get there first.”

He heard the Americans before he saw them.

Engines. Deep, powerful, smoother than the stuttering tractors back home. He crawled up the side of a ditch and peered through the branches of a straggly bush.

They came in a line down the muddy road. Jeeps first. Then trucks. Then tanks.

The tanks terrified him. Not because of propaganda this time, but because of sheer size. They were bigger than anything he had imagined. Shermans, he’d heard the word whispered by older boys who pretended to know about such things. They rolled over potholes without slowing.

He watched, heart pounding, as the convoy passed.

He saw faces. Men in helmets and strange webbing, their uniforms a dusty green-brown. They looked tired. Some smoked. One sat sideways on the back of a truck, reading a newspaper.

They did not look like the creature on the posters.

They looked like… men.

When the last truck passed, he realized he was shaking. The convoy had moved on. The road behind it was empty.

Then he saw the sign.

A wooden stake by the side of the road. Nailed to it, a crudely painted arrow and a word he could only just make out.

Amerikaner. 3 km.

He swallowed. His legs felt made of straw.

Three more kilometers.

By the time he saw the camp, the fever had deepened.

The trees opened onto a clearing. Tents. Trucks. A perimeter of wire. Guards in foxholes. Everything he had been taught to avoid.

Klaus stepped out anyway.

The searchlight snapped onto him at once. Blinding white turned the world into sharp-edged shadows. He threw up his hands, blinking.

“Halt!” someone shouted.

He stopped.

“Drop your weapon!” came next, crackling through a loudspeaker in mangled German.

He laughed weakly. “Ich habe keins!” I don’t have one. “Ich… I have no gun!”

“Hands up!” another voice shouted. That much English he understood.

He raised his arms higher. His vision was tunneling, the circle of light the only thing that seemed real.

“Come forward!” the first voice yelled. “Slowly!”

He tried. His feet tangled. The world tilted. His knees hit the mud. His palms followed. The last thing he saw before darkness swallowed him was a pair of American boots splashing toward him and a voice saying, “Jesus Christ, he’s just a kid.”

He woke to light filtered through white canvas.

The first breath hurt. The second hurt less. Something prickled in his arm. An IV line. He turned his head. The world moved too slowly.

“Easy,” a voice said, rough but not unkind. “Welcome back.”

Klaus blinked. A man sat on a wooden crate near his cot. Olive drab uniform. Corporal stripes. A face lined with fatigue and stubble. Eyes the color of stale coffee.

“My name’s Tom Schneider,” the man said. His German was clumsy but understandable. “My Oma came from Bayern. You know Bayern?”

Klaus nodded slightly.

“You walked a long way,” Schneider said. “Two days. Maybe three. Your feet looked like raw meat. Doc says you have pneumonia. That’s why you passed out. Tough kid.”

Greta.

The thought slammed into him.

“My… my sister,” he croaked. His throat felt like sandpaper.

Schneider leaned forward. “Yeah. The note. We found it.”

He held up the scrap of ration card, now lying on the lid of an ammo crate. The pencil marks were smudged but legible.

Please help my sister. She is 9. Her leg is crushed and infected. She will die without medicine. My name is Klaus Müller. I walked to find you.

“We’re still trying to decide if you’re brave or nuts,” Schneider said.

“Is she…?” Klaus couldn’t finish.

“We don’t know yet,” Schneider said, and for the first time his voice lost its joking edge. “But we’re going to find out.”

He stood. “Stay here. Don’t die while I’m gone. Doc would be pissed. I’ll get the captain.”

Klaus lay there, staring at the canvas ceiling. Somewhere outside, engines idled. Men shouted. A dog barked. It sounded like another planet.

“Brave or nuts,” he whispered. Then closed his eyes again.

Captain Miguel Torres was not what Klaus had imagined the enemy commander would look like.

For one thing, he was small. Narrow-shouldered, dark-haired, with skin the color of coffee mixed with too much milk. No iron jaw. No steely-eyed glare. Just a man in a slightly cleaner uniform with a map under one arm and exhaustion clinging to him.

“Private Schneider tells me you walked here from Düren,” Torres said, in German that was nearly perfect.

Klaus nodded.

“Do you know how far that is?” Torres asked.

“No.”

“Two hundred kilometers.” Torres whistled softly. “No wonder you dropped like a stone at the gate. You’re either the bravest kid I’ve ever seen or the dumbest. Maybe both.”

Klaus didn’t smile.

Torres’s face sobered. “Tell me about your sister.”

Klaus did.

He talked about Hülstraße. About the butcher’s cellar. About the veterinarian with three bandages and 200 patients. About the smell.

He had to stop once, when his throat closed around the words “too late even for amputation.” Schneider went out and came back with water. Klaus drank and kept going.

When he finished, Torres sat very still.

“We’re short on everything,” the captain said finally. “Men. Fuel. Time. We have orders. We’re supposed to be pushing east, not running rescue missions.”

Of course. This was the moment. The refusal. The part of the story where the American laughed and walked away.

Torres leaned forward.

“But I’ll be damned if we let a little girl die ten miles from our camp when we have medicine and those bastards back there don’t,” he said quietly. “We’ll send a team.”

Klaus stared. “Why?”

Torres blinked. “Because she’s nine.”

“We’re… we’re Germans,” Klaus said. “We… we killed your men.”

Torres’s mouth tightened. “You? No. Some other German maybe. Wear that guilt when you’re older. You’re a kid who walked until your lungs gave out to save his sister. Your country’s government wants me to hate you. My government wants me to defeat your army. Neither one told me I had to let a child die on my doorstep to feel good about it.”

He stood. “Patterson!” he called. “Schneider! Front and center!”

A man in a stained medical jacket stuck his head in the tent. Doc Patterson. Big shoulders. Hands like shovels. Eyes surprisingly gentle under bushy eyebrows.

“We’re going into Düren,” Torres said.

Patterson raised an eyebrow. “Funhouse ride. What’s the prize?”

“Little girl with a busted leg and a bad infection,” Torres said. “Our young friend here says she’s holed up in a church basement. The locals can’t do jack.”

Patterson didn’t hesitate. “Then what are we waiting for?”

Torres sighed. “The part where I get court-marshalled, probably.”

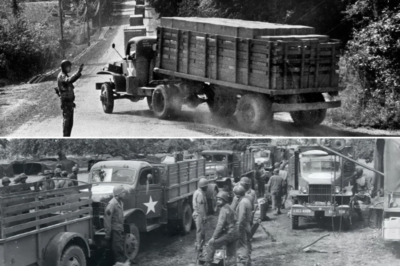

The convoy rolled out at dawn.

A jeep in front. Truck behind. Eight men. Schneider in the passenger seat of the jeep, map on his lap. Patterson and his medical kit in the back of the truck, sitting on ammo crates, checking his supplies: sulfa drugs, morphine ampoules, sterile bandages. It was more medicine than Klaus had seen in his entire life.

The road to Düren was a skeleton.

Bridges broken. Trees shattered. Houses burned. Torres swore softly when they reached the outskirts.

“Christ,” he said, slowing the jeep. “You sure your sister’s in here?”

Schneider pointed. “Kid says church on Hülstraße. Or what’s left of it.”

The town looked like a giant had stepped on it.

Streets filled with brick and twisted metal. The air still smelled faintly of burnt flesh. A dog trotted through the rubble, ribs showing, a child’s shoe in its mouth.

They found the church by its bell tower, which still stood, cracked but upright. The rest was a shell. The stained glass windows were gone. The pews had been thrown out. Inside, on the stone floor, rows of pallets.

The sound hit them when they stepped inside. Coughing. Groaning. Muttered prayers. The shuffling of feet.

Patterson’s eyes scanned the room quickly. Pneumonia. Infection. Trauma. He could see the stories on their bodies.

“We’re looking for Greta Müller,” Schneider called in German. “Nine years old. Hurt leg. Anyone know her?”

It took a moment. Then an old man in what had once been a butcher’s apron, now stiff with dried blood, looked up.

“You’re the Americans,” he said. It wasn’t a question.

“Yes,” Schneider said. “We came for Greta.”

The old man’s face twisted with something like hope and anger mixed. “Greta. She’s over there.”

She looked smaller than Klaus had described.

Curled on a pallet in the back corner, under a threadbare blanket, she barely seemed to take up any space at all. Her hair clung to her forehead in damp strands. Her skin was a waxy gray, except for spots of fever red on her cheeks. The smell around her was sweet and rotten. Gangrene.

Patterson knelt. Placed a hand on her forehead. It was a nurse’s touch, not a soldier’s.

“Hey there, sweetheart,” he said quietly. “Name’s Doc. Your brother sent us.”

Her eyes opened a crack. Brown, unfocused, but she tried to lift her head.

“Where’s Klaus?” she whispered in German.

“He’s waiting for you,” Schneider said. “But first, Doc here has to fix your leg.”

He peeled back the blanket.

Patterson had seen worse. He’d seen everything. North Africa. Sicily. Italy. He’d pulled shrapnel out of men’s guts while artillery shook the tent poles.

He still winced.

The lower half of her leg was swollen and mottled. The skin, where it wasn’t purple, was starting to go greenish-black. The toes were cold.

He looked at the butcher-apron man. “They would have cut it off,” the man said. “If we had anything to cut with.”

“Too late for that now,” Patterson muttered. “We’ll do what we can.”

He knew they should have done the amputation days ago. He knew that even now it might be the only way. But he also knew that without an operating theater, without proper preparation, trying to take the leg here might kill her faster than the infection.

He looked at Schneider. “We’re getting her out of here. Now.”

“You can’t move her,” the butcher protested. “She’s too weak.”

“She’ll die if we don’t,” Patterson snapped. “She might die if we do, but it’s the only chance she’s got. Help me with this splint.”

They carried her back through streets that had ceased to mean anything but rubble.

Patterson rode in the back of the truck, holding the IV bottle in one hand, Greta’s small, limp wrist in the other, feeling for any sign her pulse was weakening. The road jolted them. Every bump sent a hiss of pain through her clenched teeth.

“Hang on, kid,” he muttered. “If you die on me after this trouble, I’ll be very annoyed.”

When they rolled back into camp after dark, Klaus was on his feet before anyone could stop him.

He stumbled toward the truck. Schneider jumped down, intercepting him.

“She’s alive,” he said simply. “Doc’s going to work on her now. You did it, kid.”

Klaus tried to thank him. The words jammed in his throat. He nodded instead, hard, until his neck hurt.

They didn’t let him inside the tent while Patterson worked. He paced outside, counting his own breaths to keep from going mad.

One-two-three-four, in.

One-two-three-four, out.

Voices floated through the canvas. Patterson’s low growl. A nurse’s higher, calm answers. The clink of instruments.

After what felt like hours, Patterson finally stepped out.

He looked like a man who’d been fighting as hard as any infantryman.

“Well?” Schneider demanded.

Patterson rubbed his face. “We cleaned the hell out of the wound, took out dead tissue. Started her on sulfa and penicilllin. It’s a mess, but it isn’t hopeless. The next 48 hours will tell.”

The next 48 hours did tell.

Greta’s fever spiked once more, then broke. The angry redness around the wound faded. The black edges of dead skin stopped advancing. The stink lessened. She slept. She woke. She asked for Klaus. She complained about the bitter taste of the medicine.

“You know what that is?” Patterson said, grinning. “That’s recovery.”

They kept her at the camp for another week. Long enough to know she’d live. Long enough for Klaus to see enough of Americans to understand that everything he’d learned about them was upside down.

They fed him three times a day. Soup, bread, even meat. Doc Patterson yelled at him when he didn’t finish.

“They let us eat meat once a week back home,” Klaus muttered.

“Welcome to the winning side,” Patterson replied.

He heard American soldiers grumble about the same food. “Jesus, stew again?” Private Denison groaned. Klaus wanted to shake him.

Once, Schneider caught Klaus staring at his plate, guilt written all over his face.

“You’re allowed to eat,” the corporal said. “You’re not stealing from your own people by chewing.”

“But my aunt,” Klaus said. “My neighbors. They’re all starving.”

“Yes,” Schneider said. “And you and your sister being dead won’t feed them.”

He thought for a moment. “Tell you what. You get strong enough to walk without wobbling, and we’ll see about sending some extra rations to Düren. No promises. But I’ll try.”

“You’d do that?” Klaus asked.

“No guarantees,” Schneider repeated. “But if I can bend the rules a little without getting my ass court-martialed, I will. You’re not the only kid in this war who deserves something decent to eat.”

Later, Klaus watched as Schneider did something that made his throat close.

The corporal was assigned to distribute rations to local civilians one afternoon. He stood beside a truck with boxes of canned meat, powdered milk, flour. The line of Germans stretched down the road. Old women. Children. Men with empty eyes.

Schneider handed out tins, brusque but fair. When a little girl with braids reached the front, he gave her an extra can.

“Don’t tell anyone,” he said in bad German, winking. “You’re my favorite.”

Klaus laughed.

He couldn’t help it.

He’d never imagined he would laugh because of an American.

Years later, when people asked him the obvious question—how could he have trusted them enough to walk into their camp?—Klaus always answered the same way.

“I didn’t trust them. Not at first,” he would say. “I trusted that if I did nothing, Greta would die. That was the only certainty I had. Everything else was a gamble.”

And afterward?

“Afterward,” he would say, “they left me no choice but to trust them. They didn’t act like monsters. I had two options: cling to the lies I’d been fed, or believe my own eyes.”

He chose his eyes.

He held onto what he had seen: the Black soldier handing him water. Patterson bending over Greta’s leg with all the care he’d give his own child. Schneider arguing with an officer about sending food to Düren. Captain Torres looking him in the face and saying, we are not the monsters your teachers told you we were.

Those images became anchors.

Years later, when he taught history in a Pennsylvania high school, he would sometimes see the posters in his dreams—the old propaganda drawings of Americans as apes. He would wake up angry on behalf of the men who had proven those drawings obscene lies.

When his students asked which side he was on—American or German—he told them, “I was on the side of whoever remembered to be human.”

He told his story so often that his family could recite it.

At his funeral, when his son stood at the pulpit, he didn’t talk about battle statistics or famous names. He talked about a fourteen-year-old boy whose faith in his own country had been destroyed, but whose belief in humanity had been saved by the people he’d been taught to hate.

And in the front row, an old woman with a limp wiped tears from her eyes and nodded with every word.

Because she remembered too.

Not the propaganda. Not the posters.

The hand on her forehead, checking for fever.

The American medic’s gruff voice saying, “She’s going to make it, kid.”

Her brother’s face, stunned, when he realized that sometimes the enemy doesn’t look like a monster at all.

Sometimes he looks like a man who hands you water and says, “You’re safe now,” and means it.

News

(CH1) When Luftwaffe Aces First Faced the P-51 Mustang

On the morning of January 11th, 1944, the sky over central Germany looked like it was being erased. From his…

(CH1) German Pilots Laughed at the P-51 Mustangs, Until It Shot Down 5,000 German Planes

By the time the second engine died, the sky looked like it was tearing apart. The B-17 bucked and shuddered…

(CH1) October 14, 1943: The Day German Pilots Saw 1,000 American Bombers — And Knew They’d Lost

The sky above central Germany looked like broken glass. Oberleutnant Naunt Heinz had seen plenty of contrails in three years…

(CH1) German Generals Laughed At U.S. Logistics, Until The Red Ball Express Fueled Patton’s Blitz

The first thing Generaloberst Alfred Jodl noticed was that the numbers, for once, were comforting. For weeks now, the war…

(CH1) German Child Soldiers Couldn’t Believe Americans Spared Their Lives and Treated Them Nicely

May 12, 1945 – Kreuzberg, Berlin The panzerfaust was heavier than it looked in the training pamphlet. Fifteen-year-old Klaus Becker…

(CH1) When German POWs Reached America It Was The Most Unusual Sight For Them

June 4th, 1943 – Norfolk Naval Base, Virginia. The ship’s gangplank creaked. The air tasted like coal dust and salt….

End of content

No more pages to load