January 1946, the war was over, but the ground still killed.

In a ruined German city, American combat engineer Paul Henderson had three seconds to decide whether to save himself or an enemy child.

The boy couldn’t have been more than eight. Thin, blond, eyes too big in a too-thin face. He stood in the middle of the street, boots half-buried in rubble, staring at something sticking out of the broken cobblestones: a dull, finned cylinder half-hidden in dust.

An unexploded bomb.

From the shattered window on the third floor, Klaus Weber saw it at the same moment the Americans did.

He saw his grandson first.

“Fritz!” he shouted, his voice raw. The sound came out useless and thin over the winter wind.

Then he saw the Americans—three combat engineers in bulky coats and helmets, 40 meters away, working over a collapsed tram line. One of them turned at the sound, saw the boy, and went rigid. Klaus expected the man to shout, to aim his rifle, to wave the child away.

Instead, the sergeant dropped his equipment and ran.

Klaus was already limping toward the stairs, bad knee forgotten, heart hammering as he stumbled down half-collapsed steps. By the time he burst out into the street, Henderson had almost reached the bomb.

“Stopp!” Klaus rasped, though he doubted anyone understood. The cold bit through his old Vermacht coat; only the insignia had changed. The fear inside him was older than any uniform.

Fritz reached toward the cylinder, small fingers stretching.

The sergeant didn’t slow. He threw himself forward in a low dive, wrapped both arms around the boy’s chest, and drove them sideways.

The world went white.

The blast wave hit Klaus in the chest, knocked him backward. For a moment he heard nothing—no sound, no thought—only a pressure like a giant hand squeezing his lungs. Dust and hot air punched through the street; glass cascaded from empty window frames like icy rain.

When he could hear again, it was a ringing, far-away sound. The place where the bomb had been was now a smoking crater. Street stones were shattered, bits of brick still pattering down from above.

And ten meters away, Paul Henderson lay on top of Fritz.

The American’s back was shredded, uniform torn open in half a dozen places. Blood soaked through olive drab and into the boy’s shirt, spreading in a warm, dark stain. Klaus’s entire body went cold. For one wild moment he thought they both must be dead.

Then Henderson’s head lifted, just a little. His face was ashen, lips cracked, but his eyes found Fritz’s. He blinked once, as if clearing dust from his vision, and smiled.

“You’re okay, son,” he whispered in halting German. “You’re okay.”

Klaus saw his grandson’s mouth move, saw tears mixing with brick dust. He limped closer on legs that felt like paper. Before he could reach them, two other engineers were there—one dropping to Henderson’s side, the other carefully lifting Fritz free.

The boy struggled for half a second, then let himself be carried, turning to look back at the man who’d thrown himself over him.

They brought Fritz to Klaus.

“He is okay,” the corporal said in broken German, placing the child into his arms with surprising gentleness. “Not hurt. Sergeant Henderson… saved him.”

Klaus clutched Fritz, feeling the frantic, living heartbeat against his chest. Over the boy’s shoulder, he watched the medics work on the American: pressure bandages, tourniquet, shouted English words he didn’t understand. They treated him as if he mattered.

And in that moment, something broke inside Klaus Weber that had held firm for twelve years.

I taught that boy to hate the man who just bled for him.

It hit him like a second explosion.

Eight weeks earlier, the city had been colder, hungrier, somehow quieter in its ruin.

In December 1945, Klaus sat on a sagging sofa in their gutted apartment, Vermacht jacket wrapped tight against the drafts. He’d torn off the insignia months earlier, but he kept the coat. Winter did not care what cause you’d served.

On the floor, Fritz was building a crooked fortress out of scorched wooden blocks. Outside, wind creaked through broken window frames and rattled loose glass in the stairwell. The city smelled of wet plaster, coal smoke, and the faint sourness of too many people cooking too little food.

“OPA?” Fritz looked up. “Har Schneider says the Americans are giving chocolate at the checkpoint. Can we go?”

The question lodged like a splinter. Klaus had been turning it over in his mind for weeks—the boy’s growing curiosity, the way his eyes followed the passing Jeeps and trucks, the new flag snapping over the Kommandantur.

“No,” Klaus said too sharply. The boy flinched. He softened his tone. “Come here, Fritz.”

The child climbed up beside him, settling under the old coat on Klaus’s lap, all elbows and bone. Klaus stared at the far wall for a long moment, listening to the rat-tat of a distant hammer as someone tried to rebuild something that used to be home.

He had not decided to be cruel. He had decided to be honest, or so he told himself.

“Listen to me, Junge,” Klaus began. “The Americans… they are not like us. They do not follow rules like we do. They are dangerous, violent people. They smile and give chocolate, but it is a trick. They want you to trust them so they can hurt you.”

“But Opa,” Fritz said, “Har Schneider—”

“I was at Normandy,” Klaus cut in. It came out harsher than he intended. “I saw what they did.” He hadn’t, not really. He’d seen bombs and tracers and the endless, terrible competence of an enemy with more planes, more ships, more everything. The stories about atrocities had come later, in dugouts and cellars, passed from officer to enlisted man and back again. American savagery. Anglo-Saxon cruelty. Jewish revenge. Convenient stories that made losing feel less like failure.

He looked down at Fritz, his son’s child—the only piece of his boy left. His son, who’d frozen and starved at Stalingrad. His wife, who’d died under an Allied firestorm in Dresden.

“I am all you have now,” Klaus said quietly. “Your mother is gone. Your father is… gone. I tell you this because I love you. The Americans are dangerous. Stay away from them. Always.”

The boy nodded solemnly, taking his grandfather’s fear and making it his own. “Yes, Opa.”

Every lie Klaus had ever swallowed hardened into certainty.

Three weeks after he watched Henderson almost die on the street, that certainty felt like poison.

The field hospital where they took Henderson was set up in what had once been a school gymnasium. The basketball hoops were gone now. In their place stood rows of metal beds, white curtains, and the low hum of overworked generators.

Klaus stood outside the door for twenty minutes before going in. His breath clouded in the cold hall. Fritz was home with Mrs. Adler from downstairs, safe, the doctor said, not even bruised.

Because that American almost died for him.

A nurse intercepted him as he stepped inside. Her English was rapid, her German accented, but understandable.

“Can I help you?”

“The sergeant,” Klaus said. “The one hurt yesterday. Henderson. Is he—?” His throat closed.

“Alive,” she said, her expression softening. “Recovering. Are you family?”

Klaus swallowed. “The boy he saved. That is my grandson.”

“Third bed on the left,” she said. “Fifteen minutes. Please don’t tire him.”

Henderson was propped up on pillows, bandages swathing his shoulder and back. He looked smaller without his gear. Younger. His eyes flicked up as Klaus approached.

“Morning,” he said in English. When Klaus didn’t respond, he switched to halting German. “Der Junge… the boy. He is gut? Good?”

“Yes,” Klaus said. The word came out rough. “He is not hurt. Because of you.”

Henderson nodded, exhaled slowly. “Good. I am glad.”

Klaus stood rigid, hands twisting in the fabric of his coat. For a moment, neither man spoke.

“Why?” Klaus asked at last. One syllable containing 12 years of indoctrination, anger, grief. “He is German. You are American. We were enemies. Why would you…?” He gestured helplessly toward the bandages.

Henderson was quiet for a long time. When he spoke, his words were simple.

“He is a child,” he said. “Kinder sind keine Feinde. Children are not enemies.”

Klaus hadn’t realized how much he’d needed to hear that sentence spoken aloud until he heard it from the mouth of the man who was still bleeding for his grandson.

He thought of all the speeches, all the slogans about total war—about “Volksgemeinschaft,” about the enemy’s children growing up to become the enemy’s soldiers. About cities as legitimate targets, about sacrifice, about hardness.

He thought of Dresden and Stalingrad and Leningrad and Coventry and Hamburg.

He thought of an American farm boy who’d flung himself on a bomb for a German boy he’d never met.

“I taught him to hate you,” Klaus said. The confession spilled out before he could stop it. “After the war, I told him you were cruel. That you would hurt him. I believed it. I wanted to believe it because then… then fighting you made sense.” He looked down at his hands. “And then you bled for him. You almost died for a child whose grandfather told him to fear you.”

He forced the last word out. “I was wrong.”

The nurse glanced over, checking the clock. Henderson shifted carefully and gestured to the chair.

“Setzen,” he said. “Sit.”

Klaus lowered himself awkwardly, suddenly aware of his age.

They talked, stumbling through two languages.

“You were soldier?” Henderson asked.

“Vermacht,” Klaus said. “France. Russia. Berlin.” He hesitated. “Normandy.”

“Iowa,” Henderson said with a tired smile. “Farmer. Three sisters, two brothers. Army since ‘42. North Africa, Italy, Normandy, Belgium. Now…” He gestured to the bandages. “Bomben.”

“We may have shot at each other,” Klaus said.

“Ja,” Henderson agreed. “Now we shake hands.” His smile turned lopsided. “Komisch. Strange.”

“Strange,” Klaus echoed. “But good.”

The next day, Klaus brought Fritz.

The boy didn’t want to go. The world had shaken under his feet twice in as many days—first under the bomb, then under his grandfather’s apology.

“But Opa, you said—”

“I said wrong things,” Klaus told him. He knelt on aching knees so he could look his grandson in the eye. “I believed lies. I told you lies. I am trying to fix that now. Sergeant Henderson wants to see that you are alright. Will you come? Will you be brave?”

Fritz took a deep breath. “I’m brave,” he said, more to himself than to Klaus.

In the ward, Henderson’s face brightened as they entered.

“Hallo, Fritz,” he said carefully. “Wie geht’s?”

Fritz hovered behind Klaus’s coat like a shy shadow.

Henderson didn’t push. He reached into his bedside drawer and pulled out a slightly squashed Hershey bar, peeling back the paper to show the chocolate.

“For you,” he said, holding it out. “Do you like… Schokolade?”

Fritz looked up at Klaus. Klaus nodded.

Very slowly, Fritz walked forward and took the bar. “Danke schön,” he murmured.

“You’re welcome,” Henderson said. His German broke down; the smile filled in the rest. He pointed to his own bandaged shoulder. “Hurt a little, but okay. You… okay. No Angst. No fear.”

“My Opa says I should say thank you,” Fritz added, his voice barely audible.

“You are very welcome,” Henderson said. Then he looked at Klaus. “But you must also… danke Opa. He learns… new Sachen. New things. Right things. That is hard. Harder than… jumping on bomb.”

Klaus felt his throat close.

Over the next weeks, the relationship deepened. Klaus had been a schoolteacher before the war; his English from those days, rusty but serviceable, came back with practice. The Americans needed translators, especially in the dangerous business of clearing unexploded munitions from streets full of children.

The captain in charge agreed to hire him as a civilian liaison. Henderson joked that Klaus made him look clever in front of his own officers: “They think I understand all those German forms,” he said, grinning. “Really, it’s all Weber.”

Klaus translated requisitions and reports. Henderson shared stories of Iowa fields and harvests. Klaus told him about school days before Hitler, about hiking in the Black Forest, about a son he’d never see again.

Outside the ward, the old poison still simmered. One afternoon, three former soldiers cornered Klaus near the Kommandantur, their faces hard and hungry.

“Weber,” the tallest hissed. “Collaborator. Working with the Americans like a tame dog. You should be ashamed.”

Klaus looked at them—men who still wore their old hate like a uniform, even in patched civilian coats.

“That enemy,” he said quietly, “saved my grandson’s life. That enemy has shown me more honor in three months than the party ever did in twelve years. You want to keep fighting? Fight your own bitterness. But do not call me traitor for choosing peace.”

He walked away, knees shaking but head high.

When he told Henderson about it later, the American frowned.

“I am sorry you get trouble because of me.”

“It isn’t because of you,” Klaus said. “It is because of them. They cannot imagine the war is over. They do not know how to live without enemies.”

Henderson was silent for a moment.

“Back home, some folks think all Germans are Nazis,” he said slowly. “My kid brother writes me letters. Tells me I should hate you all. I write back and tell him about you, about Fritz. I’m not sure he believes me yet.”

“Do you?” Klaus asked.

“Yes,” Henderson said simply. “Or I would not be here.”

When Henderson’s deployment ended in 1948, the farewell at the station was harder than any parting Klaus had experienced in uniform.

Fritz clung to Henderson’s waist, crying openly. Henderson knelt, hugged the boy, and murmured in his improved German, “Grow strong. Learn both languages. Build bridges.” Fritz sniffed, laughed through tears at the American’s accent.

Then Henderson stood, face lined with age and pain that had nothing to do with his wounds.

“Take care of him,” he said.

“Always,” Klaus replied. “And you—go home, Paul. Be happy. You deserve it.”

They shook hands. Then, breaking all his own rules about reserve, Klaus pulled the younger man into a brief, hard embrace.

“You will have two people in Germany who think of you every day,” he said into Paul’s shoulder. “Not as an American. As family.”

The letters began a month later.

Paul wrote from Iowa about the stubbornness of corn, the fickle moods of hogs, the way the sky could swallow a man on the prairie. Klaus wrote from Frankfurt about classrooms with no windows and eager faces, about chalk dust and new textbooks, about the strange comfort of teaching verbs instead of slogans.

He told his students the truth.

“I fought for Germany,” he said on their first day. “I believed what I was told. I did not question enough. I even taught my own grandson to hate people he had never met. And I was wrong. I did not join the party. I did not beat anyone. But I was silent when I should have spoken. That is its own kind of guilt. So I will not be silent now.”

He told them about a January morning and a bomb in the street. About a man from Iowa who chose to bleed for a child he didn’t know.

“We were taught that strength means hardness,” he told them. “That mercy is weakness. But that day, I saw the opposite. The hardest thing in the world is to see your enemy as human and act like it.”

Paul told his kids about Klaus.

He kept the German’s letters in a box by his bed, carefully folded. In 1972, when Klaus died, Paul flew back to Germany for the first time since he’d left. He stood beside a grave in a small Frankfurt cemetery, the cold seeping into his shoes, and said, “He taught me that admitting you were wrong takes more courage than any battlefield.”

Paul died in 1989, surrounded by children and grandchildren. Among his papers, they found two dozen letters from Klaus and Fritz, spanning four decades. On top of the bundle was a handwritten note:

“These letters are proof that peace is harder than war. Read them. Remember them. Choose compassion.”

Today, in Frankfurt, there is a small bronze plaque on a quiet street.

It marks the spot where an unexploded bomb once lay and where a decision was made in three seconds that would echo for generations.

They were enemies. They became friends.

The inscription below reads:

“Transformation is always possible when we have the courage to choose it.”

Underneath is a line from one of Klaus’s letters, written in 1965:

“The hardest apology is to yourself, admitting you lived years believing lies. The most important apology is to those your lies hurt. And the greatest gift is when someone accepts that apology not with words, but with a life lived in friendship and grace. Thank you, Paul, for accepting my apology with your entire life. We both bled for that peace—you literally, me inwardly. I would not trade that wound for anything.”

Some wounds never fully heal.

This one did something better.

It healed two men, one family, and a little corner of the world that had been taught it was impossible.

News

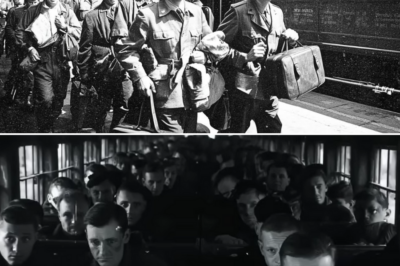

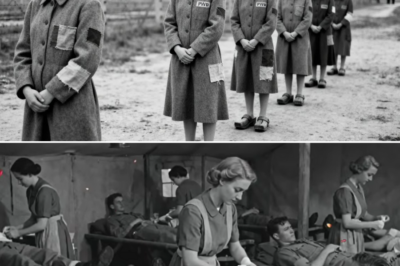

(CH1) German POW Nurses Said: “You Treat Us Well, How Can We Help?” — “Heal Our Wounded”, Said The General

When the trucks stopped at Camp Rucker, the Alabama sky looked wrong. It was too big, too blue, too indifferent…

(CH1) Captured German Nurses Were Shocked With American Medical Abundance

The first thing that hit her was the smell. Not blood, not gangrene, not the sour stench of bodies crammed…

(Ch1) When German POWs Reached America They Saw The Most Unexpected Thing

The first thing that hit him was the smell. Not coal smoke or cordite or the sharp bite of disinfectant…

(Ch1) Female German POWs Didn’t Expect New Shoes—and Socks—in America

The order came in English first, then in rough, accented German. “You’ll remove your shoes now.” The voice was flat,…

(Ch1) This 19-Year-Old Was Flying His First Mission — And Accidentally Started a New Combat Tactic

By the winter of 1943, the sky over Europe was killing American pilots faster than the factories at home could…

For years I thought the woods behind my house were just a place to clear my head after long days, a quiet trail where I walked Max and tried to outrun the kind of loneliness you don’t admit out loud

The first thing I heard was my daughter screaming. Not a pain scream. Not the weak little cough-laced sounds I’d…

End of content

No more pages to load