The day everything changed started with a silence so wide it felt like a sky. David Jackson stood on the front porch of the old farmhouse outside Charlotte and listened to it. The fields stretched away in every direction, winter-brown and sleeping. In the distance, the river moved the way it always had. Wind brushed the bare branches. The house behind him creaked and settled. For a long time, nothing else.

The land had been in his family since the first Jackson could legally sign his name under a deed. His great-grandfather had bought it with money saved in coins and folded bills after emancipation, hired himself out where he could, planted where he was allowed until he bought a corner of earth that answered to no one but him and the sky. His grandfather had farmed it with mules and then with a tractor he called “the green mule.” His father had spent a life doing what the land demanded—mending fences, fighting drought, counting calves at dawn—and taught his son to do the same.

“Son,” he used to say, a rough palm resting heavy on David’s shoulder, “they don’t make more land. Men will make paper and call it law. They will shake hands and call it truth. But dirt is dirt. Hold on to it. Don’t let anyone—no matter what they wear or how they smile—tell you it belongs to them.”

David, now in his late fifties, had believed him. He kept every paper like another fencepost. Deeds in a metal box. Survey maps rolled into tubes and tied with twine. Tax receipts in a folder so thick it had to be taped shut. He didn’t shout. He paid the county on time. He walked the boundary lines the way other men walked laps around a park. Protection for him looked like preparation.

In the spring, the silence shifted. At first he thought the noise he heard was highway work. Then the bulldozers came and the trucks behind them. Men in hard hats drove straight across his property, cutting down pine, scraping topsoil into mounds, and setting rebar where he used to find arrowheads after a rain. David stood on his porch and watched the first week, then the second. He didn’t wave his arms. He didn’t march down and plant his body in front of a blade. He kept his hands in his pockets and took note of license plates.

Word moved ahead of him into town. Martha Jenkins, a retired teacher who brought him peach cobbler each summer with a folded note that said Add more sugar if it ain’t sweet enough, showed up at his gate, breathless and pale.

“David, you can’t let them. They’re building right on your daddy’s fences,” she said, pointing past him, anger making her hands tremble. “They can’t do that.”

“They can try,” David said. He watched a concrete truck burp wet gray into a trench. “Let them. Finish. Every brick they put down will be mine a second time.”

His younger cousin Michael, all flame and fight, arrived a day later in a pickup with more rust than paint. “You gon’ just stand there?” he shouted, slamming the door hard enough to startle birds from the crepe myrtle. “If Uncle James was alive, he’d be down there turning all that machinery into scrap.”

“That’s what they expect,” David answered. He didn’t raise his voice because the truth didn’t need volume. “We go down there and break what they built, we become the story. They’ll call the sheriff, they’ll get a paper signed, and we’ll spend the next ten years telling people we’re not what those papers say we are. No. We let them walk themselves onto our side of the line. Then we show them what our paper looks like.”

The neighborhood rose while the tomatoes grew in David’s garden. Streets appeared first, then light poles and fire hydrants with blue caps that meant a good water line. Houses came out of the ground like a card trick—foundations, frames, roofs, siding—until there were rows of identical dreams. Moving trucks arrived like a miracle and doors opened onto wool rugs and new couches still smelling like the store. Children rode their bikes in circles. A young woman on a porch hung a fall wreath made of plastic pumpkins and told her neighbor across the street that it already felt like home.

No one knocked on David’s door to ask who the field belonged to before it was cul-de-sacs. The man at the front of their new association would have told them if they’d asked. His name was Richard Wittmann, a tall man with neat silver hair and a British accent that made even apologies sound like commands. He stood before rows of folding chairs in a borrowed cafeteria and told his people about vision.

“This land was wasted,” he said, smiling as if generosity had built the place. “We’ve turned it into something. A community.”

Behind him, a banner with the neighborhood’s name rippled in the air conditioning. He did not mention the Jackson family. He did not mention deeds. He did not mention law.

David drove into Charlotte and asked to see a lawyer.

Angela Brooks did not decorate her office with things that didn’t serve a purpose. A plant in the corner because it improved the air. A painting because someone she loved made it. A row of law books that were mostly digital now but could be heavy in the hand when they had to be. She was in her forties, precise in her speech and her suits, with glasses that magnified an expression that made people tell the truth faster.

She spread David’s papers on the table between them like a path you could follow out of a forest. Certified deeds with ink older than her grandmother; surveys stamped by three different companies and the county in four different decades; receipts for taxes paid every year since anyone could find records to show it; a photograph of David’s grandfather mending wire on the northern fence in 1953, a photo of his father, James, with a new tractor in 1972, David in a ball cap in 2001 with a boy’s grin and a hammer.

She paged through each, circling signatures with a finger, checking dates and notations, then leaned back. “Mr. Jackson,” she said, and smiled the way a person smiles when the thing in front of them is going exactly the way she needs it to go, “this land is yours. It has always been yours. They didn’t buy title. They didn’t get an easement. They didn’t get permission. They didn’t even file a notice. And now they’ve attached a hundred and twenty-six houses to your claim.”

“What happens next?” David asked.

“We file,” Angela said. “And we write a letter to the registry so no one else can close on a property before the court speaks. No one sleeps on your paperwork, Mr. Jackson. Not anymore.”

Letters went out to porches where seasonal wreaths swayed in late summer storms. Some people ripped them open at the mailbox and squinted as if the words might look different if they stood in a different light. Others set them on the hall table where keys and backpacks waited and didn’t open them until the house was quiet. A woman named Sarah Miller read hers at the kitchen island while a toddler asked for a snack and a baby grunted in a swing. “Thomas,” she called, and her husband came running from the garage with a handful of tools and a face he couldn’t keep steady. They read it twice. Then again. They called the bank. The bank said the title insurance company would call—tomorrow, next week, then soon. They called the HOA. The HOA said it was a misunderstanding.

In a conference room with glass walls, Richard told his board to hold the line. “We’ve broken ground, homes are sold, families are moved in. We are too far along to be threatened by a deed book,” he said. He checked his watch, and no one asked him what a deed book was.

The first hearing filled the courtroom to its corners. The benches creaked under the weight of a hundred bodies and their worry. Reporters clustered at the back, pens and cameras ready. It smelled like old wood and paper and the coffee of people who didn’t sleep.

Angela stood and laid out the Jackson story without adjectives. “Your Honor, Exhibit A: the original deed recorded in 1890; Exhibit B: subsequent transfers within the family; Exhibit C: county tax receipts paid every year since; Exhibit D: certified surveys, including the 2009 county-wide update; Exhibit E: photographs establishing continuous possession and maintenance. The defendant HOA acquired no title, filed no petition, produced a defective legal description, obtained permits on land it did not own, and built over a recorded boundary. That is trespass. Mr. Jackson asks for quiet title and equitable remedies the court deems appropriate—including ejectment against the association and damages for the encroachment.”

The HOA’s lawyers tried a different story. They called the land abandoned. They called it fallow. They called David careless with his heritage. They shifted blame toward builders and banks and a county clerk who had signed off; they insisted the train had moved too far down the tracks to put it back.

Judge Williams, a large man with a soft voice people learned to lean in to hear, watched, asked, made notes. He had been a property lawyer before he wore a robe. He knew the difference between dirt and paper.

He adjusted his glasses and read from the bench.

“Title to the land described in the original and subsequent Jackson deeds is hereby quieted in Mr. David Jackson. The court enjoins further construction and transfers. The court acknowledges the presence of innocent purchasers who relied upon defective approvals. As to the association and developers, damages will be set at a separate hearing; for the individual homeowners, the court will consider equitable remedies, including—but not limited to—ground leases under the Jackson trust or rescission with restitution. Counsel will confer and present proposals within thirty days.”

Gasps rose like wind. Someone in the back sobbed his wife’s name. Richard’s face went a color not included in dress shirts. Angela put a hand on David’s arm, brief and firm. He breathed out slow.

Outside, cameras made noise where the land had given him quiet. Microphones moved. “Mr. Jackson, do you have anything to say to the families living in those homes?” a young reporter asked.

David kept his eyes where he had learned to put them—level, steady. “It wasn’t them who cut my fences,” he said. “They were sold something that didn’t belong to the seller. I won’t pretend I’m not angry about the way I was ignored. But my fight has never been with the people setting up beds in those rooms. It’s with the men who brought trucks onto my side of the line because they knew they could count on our silence. They were wrong.”

The story traveled because it fit in people’s mouths. At the diner, a man with flour on his apron said, “Did you see that?” At the church, after the service, a woman with gray hair and a surveyor brother said, “There’s a reason we keep paper.” At a park, while one child pushed another on a swing, a woman said, softly, “I hope he’s kind,” and her friend answered, “I hope the HOA pays through the nose.”

Martha came by with a pie she’d baked too long because worry makes you forget. “Your father would’ve sat taller today,” she told David, pressing the dish into his hands. “I never knew your grandfather, but I know his name well enough to think he’s listening, too.”

Michael, who had wanted to turn back the bulldozers with his hands, leaned against the porch rail and watched the sun go down. “You were right,” he said finally. “You made a trap out of being ready.”

It took months to sort the pieces into places people could live with. Angela drafted documents for a land trust with the Jackson name on its letterhead. The trust offered ninety-nine-year ground leases to homeowners who wished to stay—an annual rent keyed to market and subsidized by the damages recovered from the HOA, the developer, the title insurer, and the bank that had funded a project on a defective title. The court ordered a restitution fund to help those who wanted to leave. The HOA board resigned. Richard did not show his face at the next meeting, and his name, months later, appeared in a smaller headline about a civil penalty and a professional sanction.

David walked the neighborhood evenings that spring. He learned the names of the dogs he heard barking—Mabel, Jax, Queenie, a tiny creature named Moose. He nodded to families in rocking chairs. He answered questions asked without hostility: “What does this mean for us?” “How do we pay?” He told his story if someone asked nice enough, and he listened even when they didn’t.

On the corner where the old oak used to throw shade, a bronze plaque went into the ground. The homeowners association and the Jackson trust agreed to it as part of settlement. It read:

THE JACKSON LAND

Purchased by Henry Jackson, 1890

Farmed by James Jackson, 1930–1990

Defended by David Jackson, 2024REMEMBER WHOSE HANDS TURNED THIS SOIL.

Respect is owed to the work that came before you.

He brought his metal box out from the safe one more time and slid this year’s receipt to the back of the pile. He put the box back and turned the key. He went out onto his porch and watched the last light skim the rooftops and settle on the far line of trees.

People said he had taken a neighborhood. He didn’t feel like that. He had taken back what men had tried to make him forget he owned. He had taken back his great-grandfather’s purchase and his father’s fences and his own careful walking of lines in the heat of July. He had taken back time.

The farmhouse did not look smaller with all those roofs between it and the horizon. Somehow, it looked more like it had found its place in the story—the way a person looks when finally seen for what they have always been doing.

“Land is the one thing they don’t make more of,” his father had said. “Hold on to it.” David had. He had not chased trucks or wrestled with men twice his size; he had wrestled with paper and memory and patience. He had won in a way that made a lesson work: prepare and keep preparing; anger burns too fast to be useful; and if you carry your family’s name like a shield into a world set up to pretend it does not recognize it, sometimes you can make even a court speak it out loud.

Years later, when the stories were told in a classroom as examples of property law and in kitchens around the county as examples of not letting people make you smaller than your deed, it was not the judge’s words or the HOA’s arrogance that people remembered. It was a man standing on a porch at dawn, watching his land, and deciding to fight the way his grandfather would have recognized.

It was a line hammered into a plaque: Remember whose hands turned this soil.

News

CHAOS ERUPTS INSIDE TURNING POINT USA — Leaked Texts from Candace Owens Just Hit the Wire, the Screenshots Were Published on Owens’ Own Show, Staff Are Scrambling, Alliances Are Fracturing, and Whispers of a Power Coup Are Spreading Fast… But What Was Really Said in Those Messages Has People on the Inside Panicking — You Need to See This Before It Disappears 👇👇👇

After the Assassination: TPUSA Reels from Candace Owens’ Leaked Texts and Legacy Rift In the wake of Charlie Kirk’s tragic…

While I was working a double shift in the ER on Christmas, my family told my 16-year-old daughter there was “no room” for her. She drove home alone to an empty house. I didn’t get angry.

At Christmas, I was working a double shift in the ER. My parents and sister told my 16-year-old daughter there…

For five years, he visited his wife’s grave, certain he knew every detail of her life. Then he found a 6-year-old boy sleeping on the granite slab, holding a photo that shouldn’t exist. What the boy said next rewrote his entire past

A bitter February nor’easter scoured the old burial ground on the outskirts of Willowbrook, Massachusetts, sending plumes of snow swirling…

After 13 years of silence, my son returned the moment he heard I was wealthy! He and his wife arrived with bags packed, expecting to move in. He thought I was the same broken woman he’d abandoned, but he was about to learn a powerful lesson…

The sun rises slowly over the quiet street, painting the porch in warm golden light. Gloria Brooke stands at the…

I came home from my work trip a day early, planning a surprise for my husband. Instead, I found a street full of cars and a party in my own home

The rain hammered against my hotel room window like bullets, each drop a reminder of the storm that had become…

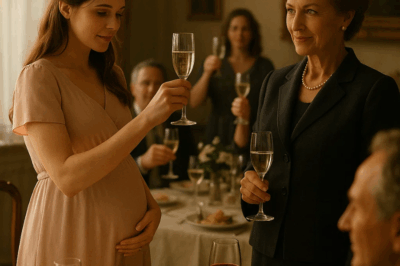

My Mother-In-Law Slipped Something Into My Glass At My Pregnancy Announcement, With A Smile That Hid Pure Betrayal. When I Confronted Her, She Hissed, ‘My Daughter Deserves To Give Birth First—Not Some Outsider.’ I Quietly Switched Glasses With Her Precious Daughter During The Toast… And Then Everything Fell Apart.

Part 1 – The Toast My name is Sarah, and I’ve been married to my husband, Jake, for three years….

End of content

No more pages to load