In the history of warfare, death usually wears a uniform. It arrives with the

thunder of artillery, the scream of Stukas, the grinding crawl of tanks.

You see the enemy. You know to run.

But in the occupied streets of Haarlem in 1943, death did not look like a monster.

It looked like a schoolgirl.

The Girl on the Bicycle

She is 14 years old.

Dark hair in two long braids that brush her shoulders as she pedals through the afternoon shadows. To the German sentries at the checkpoints, she is invisible. Harmless. A child running errands for her mother.

They smile at her.

They wave her through.

They do not check the wicker basket on her handlebars.

That mistake will cost them their lives.

Hidden beneath a dirty cloth, nestled between schoolbooks and groceries, lies a loaded FN Browning pistol. And the girl with the braids knows exactly how to use it.

Her name is Freddy Oversteegen.

She is not riding home to play with dolls.

She is hunting.

Before the Gun: Hunger and Ideals

To understand how a child becomes an assassin, you don’t start with the gun.

You start with the hunger.

Freddy Oversteegen was born in September 1925 near Haarlem, into the grit of the working class. Her family lived on a barge that smelled of stagnant water and coal dust. Money was scarce. Stability was nonexistent.

Her father was a dreamer who sang French songs but couldn’t keep bread on the table. The iron in her blood came from her mother, Trijn Oversteegen.

Trijn was a communist in a time when that label made you a target for everyone. For her, politics wasn’t theory. It was survival. Jewish and communist refugees from Eastern Europe slept hidden in the dark hold of their barge. Freddy and her older sister Truus learned their first lesson in resistance before they could read:

When humanity is on the line, you do not look away. You act.

When the marriage failed, the family moved into a cramped apartment in Haarlem. The straw mattresses got thinner. The clothes more worn. But dignity stayed.

Trijn enrolled her daughters in the Dutch Communist youth movement. While other girls learned embroidery, Freddy and Truus made dolls for children orphaned by the Spanish Civil War. They didn’t fully understand fascism yet, but they knew: somewhere out there, very bad men were marching.

Then the sky fell.

Occupation

May 10, 1940. German troops poured into the Netherlands. The Dutch army fought, but in five days it was over. The queen fled to London. Rotterdam’s center burned under Luftwaffe bombs.

In Haarlem, swastika flags appeared on government buildings. The sound of jackboots on cobblestones became the new heartbeat of the city.

Most people lowered their heads and tried to survive.

The Oversteegen family started fighting.

It began with paper. They printed illegal pamphlets in their living room, the press so loud they posted lookouts on the corner. Fourteen-year-old Freddy and sixteen-year-old Truus went out at night with pots of glue and flyers.

Wherever the Germans pasted up Arbeit in Deutschland posters urging Dutch workers to go to Germany, the girls covered them with warnings:

“Don’t go. For every Dutchman working in Germany, a German soldier goes to the front to kill.”

It was dangerous and illegal.

To the occupiers, it was a nuisance.

That changed in 1941.

“Are You Willing to Use Weapons?”

One day a man knocked on their door.

Frans van der Wiel, commander of the Haarlem Council of Resistance. A serious man who lived with the constant knowledge that torture and execution were one step away.

He sat in their shabby living room, looked at Trijn, then at the two girls.

He knew about the posters and pamphlets.

He hadn’t come to scold them.

He had come to recruit them.

They needed couriers who could slip through checkpoints. Scouts to watch German airfields. And they needed something else:

Liquidators.

“Are you willing to learn to use weapons?” he asked.

The room went still. This was no longer ink and glue. This was treason, punishable by death.

Truus asked the only question that mattered.

“Will we have to kill people?”

Frans didn’t lie.

“Yes. But not just anyone. Traitors. SS men. The ones hunting Jews. The ones sending families to the camps.”

The girls looked at their mother.

No mother wants to send her children into that darkness. But Trijn looked out at a world where roundups had begun and boxcars rumbled east.

She nodded.

But she gave them one rule:

“Always stay human. You must never become like them.”

Freddy would spend the rest of her life wondering if she had failed that rule.

Learning to Kill

Their training ground was an underground potato shed. It smelled of damp earth and mold.

Frans pressed a revolver into Freddy’s hand. It was heavy and cold.

“Aim,” he said. “Squeeze. Don’t yank.”

She fired. The blast in the cramped space was deafening, the recoil jarring her arm. She hit the target.

Again.

And again.

She learned how to strip and clean a pistol. How to prime a grenade. Where to attach dynamite on a rail line to derail a troop train.

She was 14.

Her first mission wasn’t murder. It was arson—a test of nerves.

The target: a warehouse full of German supplies. The plan: seduce the guards’ attention.

Freddy and Truus put on lipstick. Let their hair down. Went to the gate and giggled at the SS men, who leered and lit their cigarettes. While the guards stared at the girls, other resistance members slipped in the back with gasoline and matches.

Minutes later, smoke billowed into the night sky. By the time the Germans realized, the warehouse was an inferno.

The girls walked away, hearts pounding.

It felt like a victory.

Killing a building is one thing.

Killing a man is another.

The First Shot

The Council soon needed more than arsonists. Dutch collaborators and Nazi police were systematically hunting Jews and resistance families.

One man in particular—a Dutch traitor—had to go. He’d sent dozens to their deaths.

Freddy was chosen.

She put her pistol in the basket under her schoolbooks. She pedaled through the gray Haarlem streets.

She spotted him.

He looked ordinary. Not a movie villain. Just a man walking, maybe thinking about lunch.

Freddy rode closer. Her hands were steady.

She reached into the basket. Her fingers closed on cold metal.

No doctrine. No backup. No time.

She fired.

The man crumpled. Not cleanly. He fell, shocked, alive, bleeding out on the pavement.

Years later, Freddy would describe the moment:

“You shoot and you realize he is human. You want to help him get up.”

But she couldn’t.

She had to ride on.

That night, the adrenaline drained. The horror rushed in. She had crossed a line that children aren’t supposed to even see.

She cried. Her mother held her.

“You saved others,” Trijn told her. “Never forget that.”

But the war wasn’t done with her.

The Girl Who Lured Nazis to Their Deaths

The resistance realized something ugly and useful:

German men underestimated pretty girls.

So they weaponized that sexism.

This tactic would later be called a honey trap, but to these teenagers it was just the next impossible order.

Freddy or Truus would go alone into bars or cafes frequented by German soldiers and collaborators. They’d sit, drink something non-alcoholic, and wait.

The men always came.

Lonely officers in crisp uniforms, full of arrogance. They saw a young girl as entertainment, not a threat.

The girls laughed. They listened to war stories. They indicated interest.

Then, at the right moment, they would lean in and say:

“Would you like to take a walk? The woods are beautiful by moonlight.”

The German would follow, thinking he was about to seduce a Dutch girl.

He walked into the trees.

He never walked out.

Sometimes resistance men were waiting in the dark. Sometimes it was just Freddy and a gun.

Imagine that walk.

Fifteen years old. Arm in arm with a man you hate. Feeling his hand on your wrist. Keeping your voice light when everything in you is screaming.

Knowing that in three minutes he will die.

Knowing it will be your finger that sends the bullet.

One such mission targeted a high-ranking SS officer, responsible for deportations. Too guarded in the city, too careful in public.

Freddy dressed in her best. Fixed her braids. Went to his usual cafe.

She reeled him in.

They walked into the woods.

He leaned in for a kiss.

He met the barrel of a pistol instead.

He looked shocked, not scared. He couldn’t understand how the child in front of him had become death.

She didn’t give him time to understand.

The shot echoed.

And once again, a teenage girl walked away from a corpse.

Saving Children in a Starving Country

Freddy and Truus weren’t only killers. They were smugglers of life.

By 1943, Jews in the Netherlands were being systematically rounded up and sent east. In Haarlem and Amsterdam, Jewish children were separated from their parents and held in crèches—the last stop before the trains.

The sisters joined operations to snatch children from these collection points.

Freddy would take a child by the hand and walk right past German guards.

“Pretend I am your sister,” she whispered. “Do not speak.”

The child might be three years old. Might not understand. Might speak only Yiddish. If they cried or slipped up in German hearing, both would die.

They moved dozens this way. Each child carried away became another blow against Auschwitz. Hidden in barns under hay. Hidden with Christian families. Hidden in plain sight.

Not all missions succeeded.

Once, during a bombing, the children in their care were killed by Allied bombs.

Freddy never forgave the randomness of that. Doing everything right, risking your life—and still losing.

It hardened something in her that never healed.

The Red-Haired Sister

Around this time, the duo became a trio.

Through the communist circles, they met Jannetje “Hannie” Schaft—a law student with a shock of fiery red hair and a spine of steel.

She had refused to sign the Nazi loyalty oath at university and gone underground. She brought brains, idealism, and even more danger.

German reports started mentioning “the girl with the red hair” in connection with sabotage and shootings. The occupiers put her on their most-wanted list.

The three women became inseparable. They shared everything—beds, food, fear.

They promised each other:

“We live together. Or we die together.”

War had other plans.

The Hunger Winter and the Last Missions

The winter of 1944–45—the Hongerwinter—turned the Netherlands into a graveyard.

German reprisals for resistance actions and railway strikes closed supply lines. People boiled tulip bulbs and wallpaper glue to eat. Thousands starved.

Most people’s only goal was surviving one more day.

The girls were still out on the tracks with explosives.

At 3:00 a.m. in minus 20°C, Freddy and Truus lay in snow planting dynamite under railway lines. Fingers numb, body shaking, trying not to jolt the fuse.

A train carrying German armor approached.

Boom.

Derailment. Steel screaming. Tanks and ammo tumbling into the night.

A victory.

Followed by reprisal.

The Germans rounded up civilians near the site and executed them.

Every time.

And Freddy knew that. The moral arithmetic kept her awake at night.

But she also knew this: if the trains rolled, more Dutch children would starve, and more Jews would die.

There were no clean choices left.

“I Shoot Better Than You”

The Germans were desperate now.

They hunted Hannie relentlessly.

She dyed her hair black. Wore glasses. Changed safe houses like socks.

On March 21, 1945, carrying illegal newspapers and a pistol, Hannie was stopped at a random German checkpoint.

The dye in her hair had faded enough to reveal the red roots.

They took her away.

For weeks, she endured interrogation and torture. They wanted names. They wanted the sisters.

She gave them nothing.

On April 17, 1945, with the war effectively lost, two men drove her to the dunes near Bloemendaal—a sand cemetery where hundreds of resistance fighters were shot.

They led her into a shallow pit.

One German guard fired. He only wounded her.

Bleeding, on her knees, Hannie looked up at her executioners and said:

“Ik schiet beter” – “I shoot better than you.”

The Dutch collaborator beside him stepped forward and finished the job with a machine pistol.

Three weeks before liberation, the girl with the red hair died in the sand.

She was 24.

Liberation Without Peace

May 5, 1945: liberation.

Crowds in orange. Canadian tanks rolling through Dutch streets. Flags, kisses, cheers.

Freddy and Truus stood among them. Nineteen and twenty-one.

Everyone around them celebrated.

They couldn’t.

They scanned the faces, hoping against hope to see Hannie among the freed prisoners.

They never did.

Later, the mass graves in the dunes were uncovered. One of the 422 bodies was female.

Freddy and Truus went to the reburial.

They buried their sister in arms with state honors.

Then they had to find a way to live with what they had done.

The War That Wouldn’t End

Freddy suffered nightmares for decades.

No one called it PTSD then. She just had “nerves.”

She would wake up screaming, see the men she shot in her bedroom, smell cordite and forest earth.

She married, had children, worked in office jobs, tried to be “normal.”

But the war never left her.

On top of the trauma, there was betrayal—from the very country she’d saved.

Because she and Truus were communists, they were politically inconvenient in the Cold War years. Other resistance members received pensions, medals, public recognition.

For decades, they did not.

“Women don’t count,” Freddy said in a late interview. “They still don’t.”

Her sister Truus became more publicly known—an artist, a writer, a face of resistance.

Freddy stayed in the shadows.

The quiet one.

The teenage assassin turned housewife.

Only near the end of her life did things change.

Late Recognition

In 2014—almost seventy years after the shootings stopped—the Dutch government finally awarded Freddy and Truus the Mobilization War Cross.

Prime Minister Mark Rutte pinned the medal on her frail chest.

She was 88.

She did not cry. She sat straight and received it with the same quiet steel she had shown as a girl in the woods.

Streets were named after them. Documentaries were made. International newspapers called them “the teenage sisters who killed Nazis.”

It was late. But it mattered.

Truus died in 2016.

Freddy followed on September 5, 2018, one day before her 93rd birthday.

Right up to the end, her dark humor stayed sharp. When a nurse asked if she was in pain, she answered:

“I’ve been in pain since 1940.”

The Question She Left Us

For seventy years, Freddy wrestled with her mother’s rule:

“Always stay human.”

Did killing make her inhuman?

We can answer her, now.

Staying human doesn’t mean never fighting.

It means fighting for someone.

Freddy used a weapon, yes. But she used it to:

derail trains carrying tanks instead of food,

shoot men who murdered children in the street,

clear a path for Jewish toddlers to grow up.

In a world where most adults kept their heads down, she got on her bike and rode toward danger.

At 14.

That is not a loss of humanity.

That is humanity pushed to its furthest edge—and refusing to break.

The Nazis promised a thousand-year Reich.

It collapsed in twelve.

Freddy Oversteegen, the girl with the braids and the gun in her basket?

She’s still here.

In every story told.

In every child whose grandparents lived because a teenager in Haarlem pulled a trigger.

In every warning that ordinary people are capable of extraordinary resistance when fascism returns.

She thought she might be a monster.

History knows better.

She was human.

Fiercely, terrifyingly, beautifully human.

News

(CH1) Admirals Called Her Chalk Trick “STUPID” – Then It Saved 48,000 Lives

At 6:43 on a raw March morning in 1943, a nineteen-year-old woman stood in a cold Liverpool basement and looked…

(CH1) How One Girl’s “SILLY” Chalk Trick Made German U-Boats Sink 3 Times Faster

At 6:43 on a cold Liverpool morning in March 1943, a nineteen-year-old woman stood in the middle of a painted…

(CH1) How One US Woman’s “Shopping Trips” Saved 7,000 Allied Pilots from Nazi Prisons

March 2nd, 1943. Marseille. The coded telegram was short, cold, and devastating. “Pat has fallen.” Four hundred kilometers away, in…

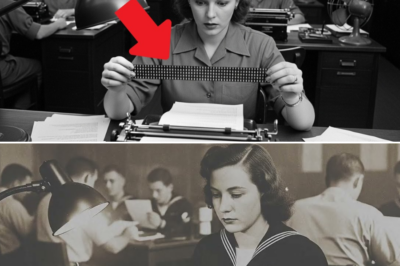

(CH1) How One American Woman’s Torn Typewriter Ribbon Saved 3,000 Lives and Sank 4 Japanese Carriers in 5 Hours

At 4:17 a.m. on May 25th, 1942, the ocean was still dark outside Honolulu, but inside the Fleet Radio Unit…

(CH1) How One Female Sniper’s “CRAZY” Trick Took Down 309 Germans in Just 11 Months

5:47 a.m. – August 8th, 1941. Belaya Tserkov, Ukraine. Twenty-four-year-old history student Lyudmila Pavlichenko crouched behind a pile of shattered…

(Ch1) How One Woman’s Bicycle Chain Silenced 50 German Tanks in a Single Morning — And No One Knew

At 5:42 a.m. on October 3rd, 1943, the gray morning light slid across Hall 7 of the Henschel & Sohn…

End of content

No more pages to load