The North Atlantic in March of 1943 was not water. It was a graveyard waiting to be filled.

Convoy HX-229 clawed its way west through fifteen-foot swells, forty-one merchant ships hauling 140,000 tons of food, fuel, steel, and explosives—all that kept Britain from starvation. On the bridge of the Liberty ship SS William Eustace, twenty-eight-year-old Captain James Bannerman gripped the rail, binoculars glued to his face as the bow plunged and rose through black water.

Somewhere out there, he knew, men were listening.

Six hundred yards off the convoy’s port beam, forty feet below the surface, Kapitänleutnant Helmut Mansack sat in the cramped control room of U-758. The red lights painted the faces of his crew the color of blood. His hydrophone operator, headphones pressed tight, eyes closed, listened to the ocean.

“Kontakt, Herr Kapitän,” the young sailor murmured. “Bearing two-eight-zero. Multiple screws. Heavy machinery noise. Estimate forty vessels.”

Mansack smiled. It was all there in the sound—the slow chop of propellers, the rumble of engines, the echo of water sliding past steel hulls. He picked up the microphone.

The wolfpack awakened.

None of them—neither Bannerman on his exposed bridge nor Mansack in his steel tube—had any idea that in the William Eustace’s galley, a twenty-eight-year-old cook named Tommy Lawson was scrubbing plates and hearing something no admiral, engineer, or scientist had noticed.

Over the next six days, the Atlantic became an abattoir. Two convoys, HX-229 and SC-122, were mauled by three wolfpacks. Twenty-two merchantmen went down in icy black water. More than three hundred merchant seamen died. It was the worst convoy disaster since 1942.

In Berlin, Admiral Karl Dönitz called it “the greatest convoy battle of all time.”

The numbers were terrifying. In March alone, German U-boats sank 567,000 tons of Allied shipping—the highest monthly total of the war. Britain’s food stocks had fallen to a three-month supply. At that rate, the island would starve before summer.

Winston Churchill, who rarely admitted fear, would later write, “The only thing that ever really frightened me during the war was the U-boat peril.”

The Allies threw everything at the problem and nothing worked.

They had Azdic—early sonar—on their escorts. It could pick up a submerged submarine at 2,500 yards. But the beam was narrow. U-boat captains soon learned to attack from outside it, on the surface, at night. Hydrophones—passive listening devices—on the German boats could hear a convoy from fifty miles away. Individual merchant ships shouted their position with every turn of their propellers from twelve miles off.

The ocean carried sound like wire. The convoys were loud.

Liberty ships like the William Eustace were acoustic disasters. Their 15-foot propellers turned at 76 rpm, gouging into water and creating cavitation—bubbles forming and collapsing with every rotation. Engines vibrated through the steel hull. Everything resonated. It all went straight into the sea, a vast underwater bell.

The Royal Navy knew the physics. Their own scientists had written it down.

To fix it, they were told, would require rebuilding the ships from the keel up.

So destroyers and corvettes zigzagged. They kept radio silence. They swept ahead with sonar that couldn’t hear past their own convoy’s roar. The U-boats simply sat and listened.

800 miles to the west of those Admiralty briefings, Tommy Lawson stood in an engine room and listened, too.

Lawson had never been meant for anything grand.

Born in South Boston in 1915, he dropped out of school at fourteen to bring home a paycheck. He learned to crack eggs and flip pancakes in a diner. Later, he learned how to cook for men at sea. By the time the war started, he’d burned his arms on too many stoves and realized that merchant ships paid three times what a Boston galley job did.

He joined the Merchant Marine at twenty-six not to be a hero, but to pay the rent.

The William Eustace was his third ship. On his off-watch hours, instead of sleeping or playing cards, he drifted down into the belly of the vessel.

The engine room was hellish. Steam pipes screamed, turbines whined, the propeller shaft thumped with every revolution, sending shivers through the deck. The engineer, a Scotsman named McLeod, thought the American cook was crazy.

“Ye’ll get yourself boiled down here, Lawson,” he barked over the noise. “This is nae tourist attraction.”

But Lawson wasn’t touring. He was listening.

All his life, he had dissected things with his senses—flavors, textures, smells. Now he was doing it with sound. He could pick out the high whine of the turbine from the low thud of the shaft, the faint rattle of loose pipe brackets from the steady hum of generators.

February 19th, 1943. Mid-Atlantic. Convoy SC-118.

The alarm sounded at 0210. A long, wailing blast. Lawson was in the engine room, crouched by the main steam line, when the ship shivered with a distant impact. Not on them—two columns over.

Through steel and water he heard it.

First the dull crump of a torpedo strike. Then a new sound. A roaring, rushing, hollow boom—water pouring through torn plates into empty holds, a ship filling with the sea. The vibration of her engines stuttered, faltered. The prop noise dropped. In seconds, it faded to nothing.

The sound was there and then it wasn’t.

McLeod swore and checked his gauges. Lawson grabbed his sleeve.

“Do you hear that?” he shouted.

“Aye, I hear it. Some poor bastard just took one amidships.”

“No,” Lawson insisted. “Listen. The sound. It stopped. When she filled with water.”

McLeod glared at him. “Of course it stopped, ye daft Yankee. She’s gone.”

But Lawson wasn’t thinking about the dead ship. He was thinking about the ones still afloat. About vibrations, about density. About the ocean as a conductor.

“What if you could put water where the vibrations start?” he yelled. “Not enough to sink her. Just… around the engines. Around the shaft. It would soak up the noise.”

“Water inside a ship is called sinking,” McLeod snapped. “Get back to your pots.”

For the rest of that voyage, Lawson filled a cheap notebook with sketches. He drew engines and shafts, hull cross-sections, and boxes. Water-filled boxes. He understood enough plumbing to know how to flood and empty a tank. He didn’t know the math behind acoustics, but he knew, in his gut, that the boiling, rushing silence he’d heard belonged in more places.

He showed the drawings to McLeod. The engineer barely glanced.

He showed them to the first mate, who laughed and told him that pipe dreams belonged in pipes.

On the bridge, Captain Bannerman listened longer than the others, then shook his head. “Son, you’re a good cook. That keeps men alive. Leave the ship fitting to those trained for it. They’ve got professors working on all this.”

But professors weren’t the ones standing next to a bare steel bulkhead, feeling the ship’s heartbeat through their bones.

When the William Eustace berthed in Liverpool in late March, the crew scattered into the city for their forty-eight hours ashore. The pubs were full of exhausted men trying to forget the torpedo wakes and the screams. Lawson didn’t go ashore.

He washed, he put on his cleanest shirt and his best attempt at a pressed uniform, and he walked to Western Approaches Command.

He got as far as the front lobby.

The two Royal Navy shore patrolmen were not impressed by the slight, grease-stained American who tried to blow past them into the nerve center of the Battle of the Atlantic.

“This is restricted, mate,” one said, putting a hand on his chest. “You want the pub, it’s three streets down.”

“I want to talk to someone about convoy noise,” Lawson said.

“We all want something.”

“It’s about the U-boats. I’ve got an idea.”

The second patrolman snorted. “We’ve got Admirals for ideas. Cooks make breakfast. Off you go now.”

They were turning him toward the door when a sharper voice cut through the lobby.

“Hold a moment.”

Commander Peter Gretton was twenty-nine, bone-tired, and furious at the ocean. He had just come back from convoy ONS-5, where thirteen ships had gone down under his protection. He hadn’t stopped seeing lifeboats in his sleep since.

“What did you say about convoy noise?” he asked.

Lawson spoke fast. He talked about the engine room, about the way the dying ship had gone quiet when water filled her. He talked about vibration traveling through steel. He talked about water as a barrier.

He used words like “insulation” and “dampening” that shouldn’t have belonged in a cook’s vocabulary.

“That’s nonsense,” Gretton said automatically. “Water in your hull is called sinking.”

“Not if you control it,” Lawson said. “Not if it’s in sealed tanks against the right spots. Around the shaft. Around the mounts. That’s where the noise starts. You stop it there, the U-boats can’t hear you.”

For the first time in months, something in Gretton’s brain clicked in a new way.

“Come with me,” he said.

What followed was three days of unauthorized, possibly insane work in a Liverpool dry dock.

Under Gretton’s authority and over the protests of Lieutenant James Whitby, the Sunflower’s engineer, they welded steel drums around her propeller shaft housing. They wedged rubber bladders against her engine mounts and filled everything with seawater.

On paper, they were vandalizing a King’s ship.

Test one failed spectacularly. At low speed on the Mersey, HMS Trespasser heard the Sunflower loud and clear.

Lawson was the one who spotted the leaks. The welds on the drums had seeped. Half the water had drained. The system had been working only half-heartedly.

“Seal them properly,” he insisted. “Then run her hard.”

Gretton closed his eyes and thought of thirteen ships going down into black water. Three more days. That’s the most he could afford before a dockyard officer—or an admiral—noticed.

They sealed the tanks. They adjusted the bladders. They tested again.

At 1,000 yards, Trespasser heard the Sunflower’s engines and propeller, loud as church bells. At 800, still heard. At 600, heard.

At 400 yards, the sound faded into the ambient noise of the river.

At 300, she vanished.

The submarine captain, baffled, surfaced and signaled, “At close range you disappeared. Your noise blended with background.”

It wasn’t magic. It was physics with oil drums and stolen hours.

In London, the idea should have died.

Experts don’t like being told they’re wrong by a man who scrubs pots.

Dr. Harold Burrus, the Admiralty’s chief naval architect, called the modification “reckless tinkering” and the test results “statistical anomalies.”

“It violates every principle of ship design,” he snapped. “You cannot simply bolt water tanks onto a hull and declare victory.”

But Gretton had the numbers. Admiral Max Horton had something else: the March casualty charts pinned to his wall, red lines climbing at an angle Britain could not survive.

He listened to Burrus. Then he listened to Lawson explain again how water absorbed vibration before it could reach the hull plating.

“Six ships,” Lawson said. His palms were sweating. “That’s all I’m asking. Retrofit six ships in one convoy. If I’m wrong, I’m wrong. But if I’m right…”

Horton stared out at the Thames for a long time.

“Six ships,” he agreed. “And if it fails, Commander Gretton, you can explain to the Board why you turned His Majesty’s corvettes into plumbing experiments.”

Convoy ON-184 sailed from Liverpool into a killing zone in April.

Forty-three ships, six of them carrying Lawson’s crude, welded-on silence in their engine rooms. The German B-dienst had decrypted their route. Thirty-seven U-boats waited.

U-264’s hydrophone operator pressed his headphones tight. “Convoy noise fading, Herr Kaleun,” he reported. “Some ships loud. Others… quiet. Very quiet.”

U-boat captains targeted what they could hear. Torpedoes slammed into hulls. Nine ships died in swirling water and burning foam.

None of the six modified vessels were hit.

When ON-184 made New York Harbor, salt-streaked and battered but largely intact, Gretton’s signal to London was almost gleeful.

After that, the idea stopped being “a cook’s madness” and became “operational priority.”

Installations spread. First to more North Atlantic ships, then to others. The system was refined: welded chambers became proper tanks, crude bladders became engineered masking layers. The underlying concept remained exactly the same: put a dense, water-filled barrier between vibration and ocean.

By summer, almost every new merchantman leaving North America carried Lawson’s silence in her bones.

U-boat hydrophones, once able to pick up convoys from dozens of miles away, started hearing ghosts. Their operators reported “contacts lost at close range,” “targets disappearing,” corridors of quiet where there should have been thunder.

German captains, who had once simply parked across convoy routes and waited, now had to close in, creeping within half a mile to hear anything. That brought them into sonar range. Into radar range. Into the eyes of lookouts who had learned what to watch for.

In May 1943, Black May, forty-one U-boats were sunk. Dönitz pulled the packs off the North Atlantic.

“This is no longer a battle,” one German officer wrote. “It is a slaughter.”

Statistics are cold, but they told the story. Before acoustic dampening: convoys lost roughly a third of ships attacked in wolfpack engagements. After: losses dropped into single digits.

Thousands of men who would have died in screaming hulls and frozen water simply didn’t.

You won’t find Thomas Lawson’s name in most history books.

He got a medal in a small ceremony. He went home. He opened a diner in Dorchester. He fried eggs and flipped burgers and yelled at teenagers to wipe their boots before they came in. He married a girl from South Boston and had three kids.

He never once stood up at a Legion hall and declared, “I helped win the Battle of the Atlantic.”

When a naval historian finally tracked him down in the late seventies, looking for “the cook in the engine room,” Lawson shrugged off the idea that he’d done anything special.

“I just noticed something,” he said. “The folks with real rank took the risk.”

But three old British officers made the trip to Boston when he died in 1991. They stood at his grave in their worn blazers and put a small, folded note into the earth.

Because of you, it said, we came home.

In the end, that’s what his idea bought: noisy convoys that became, for all practical purposes, whispers on the ocean. U-boat captains hearing nothing where once they’d heard easy prey. Liberty ships slogging through storms with their hearts wrapped in water and steel.

A cook had looked at a problem everyone else had declared impossible and asked, “What if it isn’t?”

In a war defined by mass production and huge systems, it was one man with a notebook in a hot engine room who saw the way sound moved through steel—and thought to stop it.

News

(CH1) Admirals Called Her Chalk Trick “STUPID” – Then It Saved 48,000 Lives

At 6:43 on a raw March morning in 1943, a nineteen-year-old woman stood in a cold Liverpool basement and looked…

(CH1) How One Girl’s “SILLY” Chalk Trick Made German U-Boats Sink 3 Times Faster

At 6:43 on a cold Liverpool morning in March 1943, a nineteen-year-old woman stood in the middle of a painted…

(CH1) How One 14-Year-Old Girl’s “Crazy” Bicycle Trick Killed Nazi Officers

In the history of warfare, death usually wears a uniform. It arrives with the thunder of artillery, the scream of…

(CH1) How One US Woman’s “Shopping Trips” Saved 7,000 Allied Pilots from Nazi Prisons

March 2nd, 1943. Marseille. The coded telegram was short, cold, and devastating. “Pat has fallen.” Four hundred kilometers away, in…

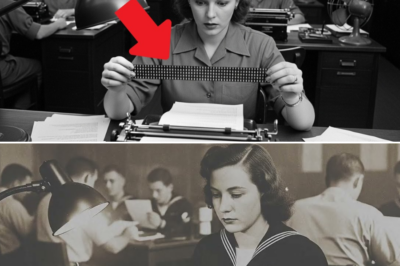

(CH1) How One American Woman’s Torn Typewriter Ribbon Saved 3,000 Lives and Sank 4 Japanese Carriers in 5 Hours

At 4:17 a.m. on May 25th, 1942, the ocean was still dark outside Honolulu, but inside the Fleet Radio Unit…

(CH1) How One Female Sniper’s “CRAZY” Trick Took Down 309 Germans in Just 11 Months

5:47 a.m. – August 8th, 1941. Belaya Tserkov, Ukraine. Twenty-four-year-old history student Lyudmila Pavlichenko crouched behind a pile of shattered…

End of content

No more pages to load