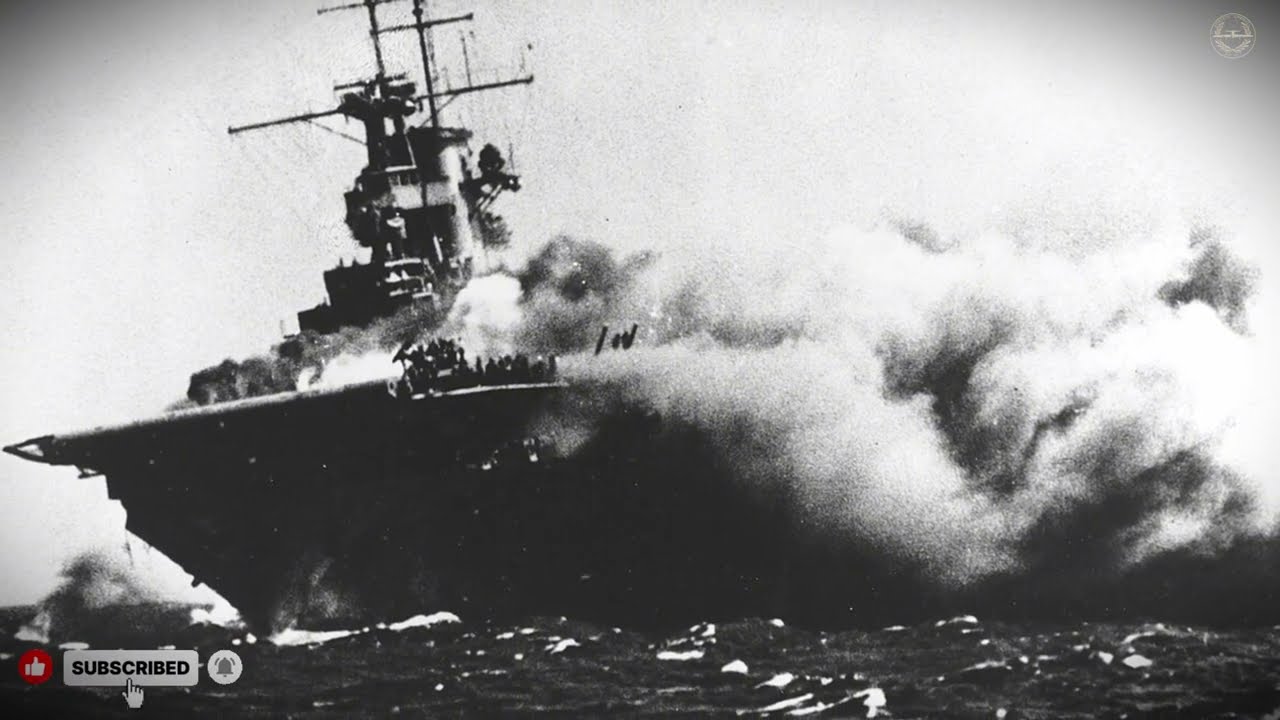

By August 1942, the name “Guadalcanal” was just a tangle of syllables on a map to most Americans. To the 16,000 Marines who waded ashore there, it was a strip of steaming jungle, a half-finished Japanese airfield, and a place that felt very much like the end of the earth.

On paper, they had done something extraordinary. In a surprise landing, the Marines had seized a vital Japanese airfield on the northern shore of the island—Lunga Point. The Japanese had been working on it for weeks, hacking a runway out of the jungle so their bombers and fighters could threaten the sea lanes to Australia. If this base became operational, the Allies’ whole strategy in the South Pacific would be in jeopardy.

The Marines took it before the Japanese could finish.

They renamed it almost casually: Henderson Field, after a Marine pilot killed at Midway. It was a victory worth headlines.

Then the rain came.

The first tropical downpour hit like a sheet of poured water. One moment the sky was simply heavy and gray. The next, it opened. The cleared strip of reddish earth that the Japanese had been calling an airfield—barely scraped level, rolled once or twice—drank all that water in one greedy gulp.

It turned to mud.

Not just any mud. Something more like a chocolate pudding of volcanic soil and clay that grabbed anything heavier than a boot and refused to give it back.

When the first American fighters arrived—the makeshift unit soon known as the “Cactus Air Force”—they approached the runway warily. From the air, it still looked like a strip of earth carved from trees. From the ground, it was something worse.

One Wildcat, wheels down and committed, touched the surface and, instead of rolling, sank. The landing gear punched through the crust into the muck beneath. Struts disappeared with a sickening lurch. Mechanics could only stare as the fighter sat nose-high in a self-made pit, engine roaring uselessly.

Another pilot tried to taxi out for a scramble when word came of incoming Japanese raiders. He throttled up. The wheels turned. The aircraft lurched—and carved trenches four feet deep before it ran out of momentum. The plane hadn’t even left the ground. It was as stuck as if it had been bolted there.

The Marines had captured an airfield.

They did not have a runway.

Japanese bombers and fighters came almost daily, swooping in from Rabaul and other bases. They found Henderson Field a tantalizing target—an island full of Marines who could not count on steady air cover. At night, Japanese ships would slide in close enough to shell the perimeter. Each barrage chewed up more of the fragile surface.

Back in Washington, the reports landed on desks with increasing urgency.

The problem was miserable and simple: how do you build a usable airstrip in a matter of days on top of mud that wants to swallow you whole?

Concrete was out. It would take months to pour and cure. There were no cement plants handy on the edge of a contested jungle. Crushed coral, used on some Pacific fields, washed away in the first serious rain. The engineers tried rolls of burlap soaked in asphalt, piling them like rugs over the ground; the first few landings tore them to shreds. Heavy steel plates were tried next, but in the tropical heat they warped and buckled, turning the runway into a kind of lethal washboard that shook planes to pieces.

Every conventional solution failed.

It was almost comical to think that America’s vast Pacific strategy—its carriers, its logistics, its island-hopping plan—could be stalled by mud. But that’s what was happening.

In a design office at Carnegie-Illinois Steel in Pittsburgh, an engineer named James Marston sifted through the failures and did something rare in engineering: he stopped trying to beat the problem head-on.

Everyone else was treating the mud as an enemy to conquer.

Marston looked at it another way. Why fight it at all?

He thought in terms of distribution, not domination. The real problem wasn’t the mud itself; it was the way weight met mud. A 30-ton bomber presses down with enormous force if you concentrate it into two skinny lines beneath its wheels. Spread that same weight over a larger area, and the ground can bear it.

So Marston didn’t design a road in the old sense.

He designed a kind of metal carpet.

It would be a flexible, interlocking system of steel planks that could be laid over almost any surface, spreading the load of each aircraft so widely that even soft ground would support it. It would “float” on the mud—not by hovering over it, but by refusing to let any one part sink too deep.

Each plank he sketched out was ten feet long and fifteen inches wide. They were punched from steel sheet and weighed about sixty-six pounds—a weight two men could manage together. But the genius lay in three features.

The first was the perforations. Each piece was riddled with 87 holes—not randomly drilled, but arranged in a pattern. They lightened the mat, of course, but they also let water drain through rather than pool on top, reducing the risk of hydroplaning. The stamped edges around each hole bit into tires just enough to give grip in the wet.

The second and third features were the ends: one side had a hook, the other a slot. To connect the pieces, you laid one down, brought the next one alongside, tilted it slightly, fit hook to slot, and dropped it. It clicked into place. No bolts to thread. No welding. No wrenches or lathes. Just that solid, satisfying “click.”

Once joined, the planks formed a continuous surface strong enough to take the beating of landings and takeoffs, yet flexible enough to move a little with the ground instead of cracking.

Someone somewhere, looking at the drawings and the test sections, decided to take a chance. The manufacturing orders went out. Steel mills stamped the new invention by the acre.

They called it Marston Mat, after the airfield in North Carolina where it was first tested. To most soldiers, it would be known simply as “PSP”—pierced steel planking.

On Guadalcanal, the first shipments arrived over a beach being raked by Japanese machine-gun fire.

The men who were told to unload the long, flat bundles were not runway specialists. They were Seabees—the Navy’s construction battalions—men who before the war had been welders, carpenters, riggers, ditch diggers. Now they found themselves dragging sixty-six-pound steel planks over sand and tucking them into stacks near the edge of a bog that pretended to be an airstrip.

A lieutenant explained how the hooks and slots worked.

Two men grabbed one end of a plank, a third grabbed the other, and together they carried it to the edge of the laid section. They lined up the slot with the hook, tilted, and let it fall.

Click.

Again.

Click.

Again.

Sometimes the sirens would wail, and the sharp cough of Japanese Zero engines would reach them over the palm trees. The Seabees dropped the planks, dove into foxholes or behind piles of earth as bombs fell. When the noise passed and the ground stopped trembling, they came out, picked up the mats, and kept going.

If a bomb cratered the section they had already laid, they filled the hole with crushed coral or whatever they had, lifted out the twisted panels, and slid new ones into place. What might have taken days to repair in a concrete runway could be patched in under an hour.

Within forty-eight hours of the first bundle being opened on Guadalcanal’s beach, a 200-foot section of Marston Mat had been laid down.

It wasn’t much, but it was enough.

The “Cactus Air Force”—so named after the Allied codename for Guadalcanal—brought in the first Wildcat fighters to land on this new surface. The planes rolled in, their wheels clattering across steel but not sinking. Their pilots climbed down, muddy and tired, and for once not furious at the field.

By September 5th, while the battle for the island still raged, the Seabees had extended the runway to 5,200 feet. It was a real airfield now, in the practical sense. Fighters could land, refuel, and scramble. Bombers could lumber in, unload, and lumber out. The mud still existed, but it had been bridged by steel.

Marston Mat solved more than a local problem.

The entire Japanese defensive strategy in the Pacific had been built on time. They fortified island after island, betting that even if the Americans took them, it would take months to build useful infrastructure: runways, fuel depots, docks. Every month spent bogged down on one island was a month Japan could use to reinforce another.

Marston Mat shattered that timetable.

On Munda Point, the Seabees laid a runway in eleven days under sniper fire. On Bougainville, they pre-assembled huge sections and laid an entire operational strip in just four days. On Saipan and Tinian, they used PSP to build the vast airfields from which B-29 bombers would later take off to bomb Japan itself. Those runways were functional in weeks, not months.

The transformation rippled outward.

Suddenly, “island hopping” didn’t just mean seizing a dot of land and pouring effort into it. It meant landing, securing a perimeter, and, almost immediately, unrolling a metal carpet to support fighters and bombers.

Planes that would have sunk to their axles in coral sand or jungle mud could now operate from almost anywhere the planking could be laid.

On the other side of the world, engineers realized they could use PSP in other ways. On the beaches of Normandy in June 1944, Marston Mat was laid over soft sand to create instant paths for tanks and trucks so they wouldn’t bog down at the waterline. Later, PSP would be used in Korea and Vietnam, wherever a “now, not later” runway was needed. In earthquake zones and disaster relief operations in the twenty-first century—Haiti, for instance—versions of that same pierced steel planking have been used to create quick landing strips for aid flights.

It never looked heroic.

It didn’t roar.

It didn’t drop bombs or fire shells.

It just lay there, row after row of 10-foot-long, hole-punched steel sections, turning useless mud into something planes could land on.

The war in the Pacific was won by carriers and submarines and bombers, yes. But it was also won by the unglamorous, ingenious idea that you could float on the problem instead of fighting it, that two men with a sixty-six-pound plank and a lot of determination could turn a patch of jungle or beach into a runway in a matter of days.

Guadalcanal had taught the Americans that the real enemy wasn’t always a soldier with a rifle.

Sometimes it was the ground itself.

James Marston’s steel carpet gave them a way to defeat that enemy—and, in doing so, helped pave the way, literally, to victory.

News

“A millionaire saw his ex-girlfriend begging on the street with three children who looked a lot like him — what happened next will break your heart.”

“A millionaire saw his ex-girlfriend begging on the street with three children who looked a lot like him — what…

He had been locked out, starved, and silenced for three years—until one snowy afternoon when someone finally asked, “Why are you outside?” and the truth rewrote their entire future.

The moment I pulled into my daughter Leona’s driveway that Thanksgiving afternoon, I felt something was wrong. Snow drifted in…

During my grandmother’s 85th birthday celebration, my husband suddenly leaned in and whispered, “Get your bag. We’re leaving. Don’t ask, don’t act weird.”

During my grandmother’s 85th birthday celebration, my husband suddenly leaned in and whispered, “Get your bag. We’re leaving. Don’t ask,…

“That necklace belongs to my daughter,” the millionaire shouted upon discovering it on the maid… The truth is shocking.

The ballroom was dazzling, illuminated by crystal chandeliers and decorated with white and gold flowers. It was a gala evening,…

A Truth That Has Been Silenced For 50 Years. The Secret Of The Concentration Camps

Number 13 Buchenwald, 1943 They always came in the evenings. Fifteen minutes at most, sometimes less. They never stayed longer…

Can’t Believe This German Women Prisoner Shocked to Ride Trains in the U.S Without Guards Watching

Story title: Open Doors 1944 Somewhere in the American Midwest When the tailgate dropped, the air didn’t smell like war….

End of content

No more pages to load