PART I: SECONDS

0710 hours. July, 1943.

Lake City Ordnance Plant, outside Independence, Missouri.

The building shook like a living thing.

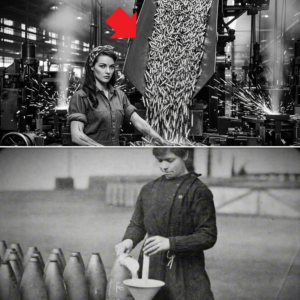

Stamping presses slammed brass into shape in violent, rhythmic bursts. Annealing furnaces radiated heat that pressed against skin and lungs alike. Conveyor belts rattled and clattered, carrying warm casings that smelled of metal, oil, and human sweat. The noise was not chaos—it was purpose, refined into vibration.

America needed ammunition.

Not tomorrow.

Not next month.

Now.

Combat reports from the Solomons said machine-gun teams were burning through hundreds of thousands of rounds in a single week. Sicily demanded more. Fighter squadrons over Europe emptied .50-caliber belts so fast that ordnance officers joked it took more ammunition to keep a B-17 in the air than to build one.

The joke wasn’t funny anymore.

Washington’s estimates were brutal and precise: to sustain simultaneous operations in the Pacific and the Mediterranean, the United States needed 2.4 billion rounds every month.

Lake City was barely producing half.

Inside the plant, nineteen-year-old Evelyn Carter pushed a cart of warm brass toward Line Four and tried not to think about the number. She had been here twelve weeks—long enough to recognize the tone of voices when supervisors talked about output, long enough to know that when engineers muttered about bottlenecks, it meant something was quietly, steadily failing.

She also knew something else.

The most delicate part of the process—the moment raw casings were fed into alignment tracks before charging and crimping—was still done by human hands, working a pattern that hadn’t changed since 1918.

Pick.

Place.

Slide.

Over and over. Thousands of times per hour.

At 0720, the day shift settled in. Six women gathered at the feeder table, arms moving in tight loops. The plant hoped for 30,000 fed casings per hour on this line. On most days it stalled at 23,000.

Seven thousand missing rounds an hour didn’t sound like much.

Scaled across twelve lines.

Across two shifts.

Across thirty days.

Millions of rounds simply never existed.

At 0726, a guide rail snapped loose.

Casings spilled across the concrete floor in a bright, metallic scatter. The line froze. A red warning lamp flashed. Supervisors sprinted. Mechanics rolled carts. The women stepped back, wiping sweat from their faces.

Everyone knew the drill.

Every stoppage meant recalibration.

Every recalibration meant lost output.

Every lost minute meant fewer rounds in a Marine’s belt.

Evelyn knelt to gather the casings. As she did, something tugged at her attention—not the mess itself, but the motion she had just watched resume.

The pattern of hands.

The looping arc of wrists and shoulders.

It wasn’t linear. It was circular.

Pick, place, slide—an orbit disguised as a line.

She froze, crouched on the floor, watching the rhythm repeat. The familiarity bothered her. It felt borrowed from somewhere else—something she had seen in a museum with her father, or in a textbook she half-remembered from school.

A machine that spun to feed something faster than human hands ever could.

She shook her head and stood. Absurd. She wasn’t an engineer. She earned eighty cents an hour pushing brass. But the thought clung to her like heat.

A rotating pattern.

Multiple stations sharing the load.

A wheel instead of a line.

At 0734, the line resumed at a crawl. Evelyn glanced at the production clock and felt a tightening in her chest. Another ten minutes gone. Another slice cut from the daily quota. Somewhere in Washington, a colonel would underline a number in red.

She wheeled her cart down the aisle.

The idea sharpened as she walked.

A rotating system wouldn’t force hands to restart with every cycle. It would carry the motion for them—continuous, steady, indifferent to fatigue. A ring of feeders instead of a row. Efficiency gained not by pushing people harder, but by letting a machine do the moving.

The shape formed in her mind so suddenly that she stopped in the aisle.

A wheel.

A drum.

A rotating star of loading slots.

Her breath caught as the name surfaced.

Gatling.

The old Civil War gun that increased fire rate by rotating barrels instead of demanding one barrel do everything. What if feeding ammunition worked the same way—in reverse?

She almost laughed at herself.

But the idea pulsed with clarity.

If rotation solved heat in a gun, why wouldn’t it solve fatigue in a factory?

By the time she reached the rear of the building, she felt a strange sensation—not inspiration exactly, but inevitability. As if the solution had been sitting in plain sight and she had simply tripped over it.

Even a modest improvement would ripple outward.

A few seconds saved per station.

A few seconds multiplied by hundreds of workers.

Scaled across twelve lines.

Across twenty-four hours.

The numbers climbed quickly. Dangerously quickly.

What she didn’t know—what she couldn’t know yet—was how that small observation born at 0726 would grow into a mechanism capable of doubling Lake City’s output. Or how its influence would stretch from Missouri to Normandy, Saipan, and the skies over Europe.

For now, she had only a half-formed idea she barely understood.

At 0800, the plant whistle screamed—a long metallic blast that rattled sheet-metal walls and signaled the official start of the day shift. The night crew shuffled out, hollow-eyed from fourteen hours of brass and heat. The day crew stepped around bins of warm casings that still smelled of copper.

Near the entrance, a clipboard hung with the morning numbers written in pencil.

Units short. Again.

The deficit looked small on paper. Tens of thousands of rounds. But scaled across coming invasions, across two oceans, those missing rounds became something heavier.

Commanders in Europe reported platoons nearly going black on ammunition. Marines at Munda burned belts faster than transports could deliver them. Quartermaster analysts warned that if output didn’t rise by 20 percent by autumn, entire offensives might stall—not for lack of tanks or planes, but bullets.

By 0807, the heat climbed past what offices would consider survivable. Lake City had been built for production, not comfort. Glass windows trapped sunlight. Furnaces warmed the air. Steam rose from coolant baths. Pocket thermometers pushed 97 degrees.

No one complained.

Complaining didn’t add brass to belts.

At 0813, a foreman unlocked a cabinet and pulled out yesterday’s production summary. The graphs were brutal. Lake City’s monthly high hovered around 1.4 billion rounds. For Washington, that wasn’t just insufficient.

It was a crisis.

Reports from Sicily said infantry units were reducing training fire because they feared they wouldn’t have enough for combat. Photocopies of letters from the front were pinned to bulletin boards as motivation.

“We’re running the guns hot enough to melt the jackets. Send more.”

Evelyn paused near Line Six as an inspector checked casing dimensions with a micrometer. Twelve thousandths too wide and the round jammed. Six too narrow and it failed pressure tests. Precision mattered—and precision took time.

But throughput was the real monster.

One thousand was manageable.

One million was hard.

One billion per month was something else entirely.

At 0825, the morning briefing began. A lieutenant from Ordnance read from a memo fresh from Washington. Consumption rates had risen nearly 30 percent. Enemy resistance was intensifying. More artillery duels. More close-range firefights. More aerial intercepts.

The margin between enough and catastrophe often came down to minutes.

Ten minutes lost to a jammed conveyor didn’t feel disastrous inside the plant. Multiply it across twelve lines, two shifts, thirty days—and hundreds of thousands of rounds never existed.

Those rounds were hills taken or abandoned.

Lives protected or spent.

Evelyn caught herself imagining what one percent efficiency looked like at scale.

Fourteen million additional rounds per month.

Five percent meant seventy million.

The war ran on numbers like that.

At 0833, the briefing ended. Workers scattered back to stations. Evelyn hesitated. She wasn’t an engineer. She had no authority. But she had eyes—and she had noticed something others hadn’t.

She replayed the looping motion of the feeders in her mind. That circular rhythm. That forgotten memory of rotation solving a problem linear motion couldn’t.

At 0911, she stood beside Line Four again. The line was running, but limping. Six pairs of hands repeated the same loop. A loop disguised as a line.

She watched without blinking.

Then her breath caught.

She didn’t see the solution fully—but she saw the shape.

A wheel.

At 0914, an inspector walked by muttering about throughput again. No one asked why the numbers lagged. They simply pushed harder.

Evelyn felt a flicker of defiance.

Trying harder wouldn’t get Lake City from 1.4 billion to 2.4 billion. Doing the same thing faster didn’t change the math.

Changing the motion might.

When the foreman turned away, she slipped toward a scrap bin near the east wall. Broken pallets. Bent brackets. Discarded slats. Forgotten parts. Her fingers closed around an oily bearing ring.

A wheel needed a heart.

At 0923, she ducked behind stacked crates and arranged scraps on the concrete—triangles, stars, circles—testing how a rotating carrier might cradle casings. She trembled, not from fear, but urgency.

She wasn’t supposed to be here.

But time was bleeding away.

At 0931, a mechanic stepped out of the maintenance shed and froze when he saw her kneeling with lumber and metal arranged in strange geometry. She blurted an explanation she barely understood—rotation instead of linear feed, throughput instead of force.

He didn’t laugh.

He asked one question.

“What problem are you actually trying to solve?”

“Throughput,” she said.

He nodded.

Throughput was a language everyone spoke.

At 0937, she spun the improvised star by hand. It wobbled. Slats slipped. It didn’t matter. This wasn’t a prototype—it was proof of motion.

By 0942, she was at a drafting table with a dull pencil. Central ring. Rotating plate. Peripheral slots angled to cradle casings. A linkage to an existing motor.

She didn’t know torque or tolerances.

But she knew frequency.

Nine revolutions per minute.

One thousand casings per turn.

Sixty thousand per hour.

Her pulse jumped at her own math.

At 0950, the foreman found her and demanded why she wasn’t at her station. She held up the sketch with shaking hands.

He didn’t dismiss her.

He said they would test it at lunch—not because he believed it would work, but because desperation opened doors.

At 0958, she returned to her line. The machines sounded louder now. She wasn’t imagining the bottleneck anymore.

She was diagnosing it.

Once you see inefficiency, you can’t unsee it.

At 1122, the maintenance crew cleared a narrow space beside Line Two for a test. Three minutes. Not four. Lunch wouldn’t wait for ideas.

At 1123, the crude wooden wheel wobbled onto a spindle. A salvaged motor flicked on. Casings scattered. Laughter rippled—not cruel, just tired.

She adjusted. Slowed the belt. Deepened recesses with her thumb.

At 1125, time was up.

Then the mechanic said, “One more rotation.”

He steadied the wheel. Lowered the speed. The rotation became deliberate.

Three casings.

They fell where they needed to.

Not success. But sense.

At 1126, power cut. The moment ended. The line roared on.

An older woman from Line Four approached Evelyn quietly and placed a casing in her hand.

“You see that dent?” she asked. “That’s fatigue. Repetition does that—to metal, to people.”

She nodded toward the wheel.

“Anything that reduces it is worth trying.”

Evelyn redrew the design during lunch. Deeper recesses. Rubber lining. A weighted rim. Then she added a second wheel. A third. Staggered rotation. Continuous motion.

At 1247, the foreman called her to the supervisor’s platform.

An engineer.

A procurement officer.

The mechanic.

All staring at her sketch.

At 1300, the procurement officer authorized a steel prototype for the night shift.

Not because he believed.

Because Lake City had run out of alternatives.

That night, sparks would fly. Steel would ring. A wheel would become something real.

And the next morning, Lake City’s world would tilt.

PART II: WHEN THE NUMBERS MOVED

0650 hours. July, 1943.

Lake City Ordnance Plant, Independence, Missouri.

The plant woke the way it always did—slowly at first, then all at once.

Cars rolled into the gravel lot. Boots hit concrete. Doors slammed. The whistle cut through the humid air like a blade. Inside, presses began their pounding rhythm, furnaces came alive, belts shuddered into motion. It felt like any other morning.

It wasn’t.

At the center of Line Two, bolted into place during the night shift, stood a machine that did not belong to yesterday. It wasn’t polished. It wasn’t elegant. It was heavy steel, scarred by welds, painted only enough to keep edges from cutting skin. A circular plate nearly thirty inches across sat on a hardened spindle. A weighted rim gave it mass. Rubber-lined recesses waited at its perimeter.

A wheel.

The foreman gathered the morning crew. He didn’t raise his voice. He didn’t promise miracles.

“We start slow,” he said. “If it fails, we shut it down. If it works, you’ll feel it before you see it.”

No one laughed.

They’d all been disappointed before.

At 0705, the plant engineer checked the motor housing and gear reduction—nine revolutions per minute. Not ten. Not eight. The number mattered. He nodded to the mechanic.

“Power.”

The switch snapped.

The motor growled low. The wheel jerked once, hesitated, then settled into a steady, deliberate rotation. Not frantic. Not trembling. A slow, confident heartbeat.

Workers leaned closer.

The first casings were placed into the recesses. The wheel carried them forward and—without ceremony—delivered them into the alignment chute.

No jam.

No pause.

At 0713, the counter ticked through the first full minute.

Five hundred.

Six hundred.

Seven hundred.

By 0715, the rate stabilized near 780 casings per minute.

The usual rate on that station had been under five hundred.

No one cheered. That wasn’t how Lake City worked. Instead, a strange quiet spread, the kind that comes when people realize something fundamental has changed and don’t yet trust themselves to say it out loud.

At 0721, they loaded a larger batch.

The wheel took it.

Rubber lining absorbed vibration. The weighted rim smoothed the rotation. Casings fell with a consistency that felt almost wrong in a building used to constant interruption.

Supervisors arrived, notebooks open, pencils moving fast. The foreman didn’t smile, but his eyes narrowed, tracking the counter like a gambler watching dice settle.

At 0730, Evelyn stood off to the side, hands clasped behind her back, trying to stay invisible. She noticed what others missed—the slight axial drift, the momentary wobble when a slot carried a heavier casing, the fraction-of-a-second delay when the chute filled faster than expected.

It worked.

But it could work better.

At 0738, the engineer pulled her aside.

“Can it scale?” he asked.

She didn’t pretend certainty.

“Yes,” she said. “But the spindle mounts need reinforcement, the stabilization ring needs more mass, and the recess curves need reshaping.”

She surprised herself with how easily the words came.

At 0744, the counter crossed a number Lake City had never seen at that hour.

80,000 casings in a single hour.

Workers froze, staring as if the machine might retract the lie.

It didn’t.

At 0750, the superintendent arrived, summoned by the foreman’s urgent call. He studied the wheel, the counter, the absence of jams. Then he looked at Evelyn.

“Can it scale?” he asked.

The question carried another one beneath it, heavier than steel: How many lives does this mean?

By 0800, the decision was made.

Three additional units authorized immediately.

Full redesign of Line Two.

Phased conversion of remaining lines if results held for 72 hours.

A memo went to Washington. No names. No stories. Just numbers.

Numbers were what mattered.

SEVENTY-TWO HOURS

The wheel ran.

Then it ran again.

By noon, Line Two’s throughput was consistently above 1.8 times its previous average. Fatigue complaints dropped. Jam reports plummeted. Maintenance logs, usually thick with red ink, stayed clean.

At 1430, Line Six jammed again—seven minutes lost, nearly four thousand casings gone. Supervisors looked from the stalled line to Line Two’s wheel, still turning, still feeding.

The contrast was brutal.

That night, the maintenance bay lit up again. Sparks flew. Steel rang. Two more wheels took shape, heavier and better balanced than the first. Engineers thickened the spindle, widened the bearing seat, reshaped the recess lips. Rubber linings were replaced with a denser compound scavenged from vehicle mounts.

Evelyn stayed past her shift, then past what she told herself she’d allow. She sketched revisions, erased them, sketched again. She wasn’t calculating tolerances—she was thinking about people. How hands tired. How mistakes crept in at the end of a long loop. How machines should move so humans didn’t have to.

By the end of the second day, Line Two was unrecognizable.

Three wheels ran in staggered sequence, each feeding while the next reloaded itself. Continuous motion replaced stop-start drudgery. Throughput climbed again.

By the end of the third day, Lake City’s daily output ticked past a number Washington had circled in red for months.

Two billion rounds per month—projected.

Not achieved yet.

But reachable.

And in a war factory, reachable changed everything.

WASHINGTON TAKES NOTICE

The call came at 0940 on the fourth day.

The superintendent listened in silence, then handed the receiver to the engineer. The engineer listened, nodded, and covered the mouthpiece.

“They want validation,” he said. “And a schedule.”

By afternoon, Ordnance officers arrived with clipboards and questions sharpened by urgency. They asked about failure modes. Maintenance intervals. Safety. Integration. They asked who designed it.

The superintendent answered with numbers.

The officers pressed.

“Who,” one of them said, “came up with this?”

The superintendent glanced at Evelyn, then back at the clipboard.

“It came from the line,” he said. “That’s what matters.”

The answer was sufficient.

By evening, authorization came to convert four more lines. By the end of the week, all twelve.

The wheel multiplied.

THE RIPPLE

By August, Lake City’s monthly output cleared 2.3 billion rounds.

By September, it crossed 2.6 billion.

Washington revised its forecasts. Sicily’s rationing ended. Units in the Solomons reported training allotments restored. Fighter groups over England received full belts without delay.

The change did not announce itself with headlines. It arrived quietly, in the absence of shortages.

That absence mattered.

At Anzio, an infantry platoon held a line through the night with ammunition to spare. In the Central Pacific, a machine-gun crew sustained fire without breaking rhythm. Over Schweinfurt, escort fighters returned with belts empty—but replacements waiting.

The war did not pause to thank Lake City.

It simply consumed what Lake City could now provide.

CREDIT AND CONSEQUENCE

Evelyn’s life changed in ways she did not expect.

She was reassigned—not promoted, not celebrated—to a small process-improvement team tucked behind the main floor. Her pay increased modestly. Her hours grew longer. Engineers asked her questions and then pretended they hadn’t.

She didn’t mind.

She cared about motion.

About flow.

About seconds.

The wheels evolved. Steel gave way to cast assemblies. Bearings improved. Recess geometry was standardized. Other plants asked for drawings. Then templates. Then shipments of components.

By early 1944, rotating feeders—descendants of Evelyn’s first sketch—appeared at ordnance plants across the Midwest.

No plaques bore her name.

But the numbers did.

THE QUIET MATH OF WAR

By the summer of 1944, Allied planners stopped worrying about small-arms ammunition. It became the first category to shift from scarcity to surplus.

Not because battles grew smaller.

Because factories learned to think differently.

A one percent efficiency gain had become millions of rounds.

A wheel had replaced a line.

And seconds, once lost forever, had been reclaimed.

At 0710 one humid morning, a nineteen-year-old had noticed a loop where everyone else saw a line.

Two months later, soldiers fired rounds that existed because someone dared to change the motion.

PART III: THE QUIET VICTORY

By October 1943, Lake City no longer sounded like a factory in crisis.

It sounded… steady.

The presses still hammered. The furnaces still radiated heat. The belts still rattled under the weight of half-finished rounds. But the frantic stops—the red warning lights, the shouted recalibrations, the long minutes lost to spilled casings—had thinned to background noise.

The wheels turned.

And because they turned, the war shifted.

WHEN SHORTAGE DISAPPEARED

Washington noticed the change the way it always noticed things: through numbers.

Monthly production reports crossed desks at the Ordnance Department showing a curve that should not have existed. A line that had crawled upward for months suddenly bent sharply, then climbed.

2.1 billion rounds.

2.4 billion.

2.7 billion.

Analysts double-checked the math. Then checked it again.

By November, Lake City alone was producing more small-arms ammunition than entire Allied nations had managed in the previous war. Other plants followed. The rotating feeder system—never called by its inventor’s name, never formally credited—spread quietly, replicated by men who cared only that it worked.

Factories in Minnesota.

Illinois.

Pennsylvania.

The wheel became standard.

No ceremonies marked its arrival. No newspaper headlines announced it. Ammunition simply stopped being the limiting factor.

That absence was decisive.

AT THE FRONT

In Italy, infantry companies stopped rationing training fire. Platoon leaders no longer told men to hold rounds “just in case.” Machine-gun crews no longer broke contact because belts ran dry.

In the Pacific, Marines landing on coral beaches fired until barrels smoked—and still had reserves. At Saipan, after-action reports mentioned sustained suppressive fire as a factor in breaking Japanese counterattacks.

In the skies over Europe, fighter groups loaded full belts without delay. Aerial commanders stopped calculating sorties against ammunition stocks and started calculating against weather and fuel instead.

The change didn’t make headlines.

It made survival normal again.

THE GIRL WHO SAW THE LOOP

Evelyn Carter never visited the front.

She never saw a beach landing or heard a machine gun fire in anger. She didn’t wear a uniform or receive a medal. Her contribution arrived wrapped in grease, steel, and arithmetic.

Her days changed subtly.

She was moved into a small process-analysis office overlooking the floor—not as an engineer, not officially, but as someone whose instincts had proven inconveniently accurate. Engineers brought her problems framed as questions.

“Where does this slow down?”

“Where do hands get tired first?”

“What motion doesn’t belong?”

She answered honestly.

Sometimes she was wrong.

Sometimes she was right enough to matter.

By early 1944, she was working twelve-hour shifts alongside men with degrees she didn’t have. No one mentioned it. War had a way of stripping credentials down to results.

Her pay rose quietly.

Her name stayed off memos.

That was fine.

WHEN THE WAR ENDED

In May 1945, Lake City slowed for the first time in years.

The presses still ran, but not at a scream. The wheels still turned, but fewer lines demanded full output. Workers gathered around radios when announcements came—Germany first, then Japan.

The factory did not celebrate loudly.

It exhaled.

In the months that followed, production lines were dismantled or repurposed. The rotating feeders were boxed, shipped, adapted for civilian manufacturing. Some ended up feeding rivets, bearings, bottle caps—anything that needed steady motion without fatigue.

Evelyn stayed on.

She enrolled in night courses paid for by the company. Learned drafting properly. Learned mathematics she had once only approximated. By the early 1950s, she held a quiet title in industrial process design.

If anyone ever asked how she learned, she gave the same answer.

“I watched.”

HISTORY, MISPLACED

Decades later, historians would write about World War II as a triumph of strategy, of generals and invasions, of tanks and planes and codebreakers. They would speak of logistics, but rarely linger on the mechanics of it.

They would not name the wheel.

They would not name Evelyn Carter.

But the math would remain.

A five percent efficiency gain across ammunition production translated into hundreds of millions of rounds. Those rounds translated into sustained fire. Sustained fire translated into ground held, assaults repelled, lives preserved.

Wars are not won only by bold decisions.

They are won by systems that stop bleeding seconds.

THE LAST MORNING

Years later, long after the plant had modernized beyond recognition, Evelyn visited Lake City one final time. The old feeder tables were gone. In their place stood sleek machines she barely recognized, all rotation and automation.

She stood behind the safety rail and listened.

The sound was different now—less frantic, more controlled. Like breathing.

A supervisor pointed proudly at a modern feeder wheel and explained its advantages to a group of visitors.

“Continuous motion,” he said. “No dead time.”

Evelyn smiled to herself.

The guide asked where the idea came from.

The supervisor shrugged.

“Hard to say. Someone figured it out during the war.”

That was enough.

At 0726 one morning in July 1943, a guide rail snapped loose and brass spilled onto concrete.

A nineteen-year-old noticed a loop where everyone else saw a line.

And because of that, millions of rounds existed when they were needed.

History remembers battles.

But wars are won by motion.

THE END

News

Ana Morales, his maid, was finishing up for the day, her six-year-old daughter Lucia skipping behind her in an oversized Santa hat. They were heading home.

By the time the first snowflake drifted past his window, the city below was already wearing its winter disguise. Edinburgh,…

I WAS SITTING CALMLY WITH MY 6-YEAR-OLD DAUGHTER AT A FAMILY PARTY WHEN SHE SUDDENLY CLUTCHED MY SLEEVE AND WHISPERED, MOM, WE NEED TO LEAVE NOW. I ASKED WHAT WAS WRONG, AND WITH SHAKING LIPS SHE SAID, DID YOU SEE WHAT’S UNDER YOUR CHAIR? I LEANED DOWN TO LOOK, MY HEART STOPPED, AND WITHOUT A WORD, I TOOK HER HAND AND STOOD UP.

I WAS SITTING CALMLY WITH MY 6-YEAR-OLD DAUGHTER AT A FAMILY PARTY WHEN SHE SUDDENLY CLUTCHED MY SLEEVE AND WHISPERED,…

I sat at the Thanksgiving table with an untouched plate, reading a note that said they were celebrating at an upscale restaurant while I ate alone.

Instead of family warmth, Thanksgiving greeted me with an empty chair and a note announcing they were dining at a…

Hungry Black Girl Found Him Shot and Holding His Twins — She Didn’t Know He Was the Billionaire Skye Jackson always took the long route home.

She found him in a puddle of rainwater and spreading blood, clutching two infants like they were the only proof…

A young man missed the interview that could have changed his life because he stopped to help an elderly woman stranded in the rain… never knowing she was the CEO’s mother. Minutes after being turned away for arriving late, a single message arrived—and everything he believed about his future was turned upside down.

The rain fell as if the sky wanted to empty itself all at once. Luis ran down the avenue, dodging…

No one dared to intervene as the billionaire CEO struck his pregnant wife—until a Black waitress uttered TWELVE WORDS that stopped the entire ballroom cold…

“Touch her again, and I swear—I’ll burn your empire to the ground.” He smirked.“Who’s gonna believe you? A Black…

End of content

No more pages to load