5:47 a.m. – August 8th, 1941.

Belaya Tserkov, Ukraine.

Twenty-four-year-old history student Lyudmila Pavlichenko crouched behind a pile of shattered brick, watching a German sniper line up a shot on a Soviet sergeant 40 meters to her left.

She’d been a sniper for exactly six hours.

No food. No sleep.

One Mosin–Nagant rifle.

Forty rounds.

Zero kills.

Three hundred and nine to go.

Four months earlier she’d been in a classroom at Kiev University, studying history. Her professor, Anatoly Vulov, lectured about revolutions and empires.

Eleven days before she enlisted, a German bomb turned that lecture hall into a crater.

Seventy-three students died.

Professor Vulov was buried under rubble for two hours.

Her best friend Natasha burned alive in the university library. The fire ate all the books and all the people inside.

The next morning, Lyudmila went to the recruiting office.

“You should be a nurse,” the officer said. “Women belong in medical units, not in the infantry.”

“I’ve been shooting since I was fourteen,” she told him. Youth shooting club, top scores, regional competitions.

The officer laughed. “Targets don’t shoot back. Combat is blood and screaming. Women can’t handle that.”

“Test me,” she said.

He handed her a rifle, pointed at a fence post 100 meters away. She put five rounds through the center.

The officer stopped laughing.

She was assigned to the 25th Rifle Division.

Sniper.

Now, in Ukraine, lying in the dirt of Belaya Tserkov, a German sniper was about to kill a man she’d met the day before.

Sergeant Dmitri Kravchenko.

Thirty-two. Married. Two kids.

He’d broken his bread ration in half and given some to her when she hadn’t eaten in 18 hours.

Now he was pinned behind a low wall, unaware that a German scope was on him.

The German sniper was 280 meters away, behind a ruined farmhouse wall. Lyudmila could see the rim of his helmet through a crack in the bricks. His attention was fixed on Kravchenko.

Her instructor’s words came back to her:

“Don’t think about killing. Think about solving a problem.

Distance. Wind. Target movement.

It’s mathematics, not murder.”

280 meters.

Light crosswind from the west.

Target stationary.

She adjusted windage. Settled her sights on the gap in the wall. Her finger took up the slack on the trigger.

This was it.

Either she could kill or she couldn’t.

Either she was a soldier or just a student holding a gun.

She exhaled, slow.

Squeezed.

The Mosin-Nagant kicked into her shoulder. The shot cracked across the battlefield. Through the scope, she saw the helmet snap back and vanish from view.

Kravchenko flinched, looked around, confused. He didn’t know he’d just been saved.

Lyudmila worked the bolt, scanned for movement. Nothing.

She had her first kill.

She felt…nothing. No thrill. No guilt. Just one clear thought:

“Where’s the next one?”

That was August 8th, 1941.

By May 1942, she would have 309 confirmed kills – including 36 enemy snipers. She would become the deadliest female sniper in history.

And the crazy thing that made that possible?

She fought doctrine.

She used herself as bait.

The first sniper Lyudmila lost was Lieutenant Anna Morozova.

August 19th, 1941.

Morozova had been in the game eight months.

Forty-seven confirmed kills.

Smart. Experienced. Textbook Soviet sniper.

Doctrine said:

Never expose your position.

Fire, then move.

Never stay in the same spot more than 30 minutes.

Never fire more than three shots from one place.

Always have a secondary position. A tertiary one if you can.

Morozova did everything right.

She set up on the third floor of a shattered apartment building. Great sight lines. Two preplanned escape routes.

She shot a German machine-gunner at 320 meters. One shot, one kill.

She moved to her second nest on the second floor. Waited twenty minutes.

She killed a German officer at 280 meters.

She started down the stairwell to her third position. A single German rifle cracked outside.

The bullet came through a broken window. Clean shot to the chest.

She was dead before the medics arrived.

A German sniper had been tracking her from the first shot. Watching. Waiting. Predicting exactly how she’d move—because she moved exactly like the Soviet sniper manual said she should.

Lyudmila was in the same building, one floor below. She heard the shot. Heard Morozova fall. Heard German voices laughing across the ruins.

That German sniper’s name was Hans Becker.

Vermacht.

Counter-sniper specialist.

Eighty-nine confirmed kills.

He hunted Soviet snipers like Lyudmila hunted German soldiers. And Soviet rules made his job easy.

The second sniper she lost was Corporal Viktor Stepanov.

August 27th. Nineteen years old. Six weeks in the field. Eleven kills. Good kid. Too eager.

He dug into a perfect drainage ditch, 400 meters from German lines. Camouflage flawless. Position excellent. Textbook again.

At dawn, he took out two Germans from that ditch. The Germans scattered, dove for cover.

Stepanov did what he was supposed to do. He stayed put. Waited fifteen minutes before moving.

German artillery fell on the ditch.

One shell, direct hit. Nothing left to bury.

The Germans hadn’t seen him. They’d just back-plotted his shot and plastered the area.

He did everything right. He died anyway.

By September, Lyudmila had watched seven snipers die. Every one of them had obeyed doctrine like it was gospel.

The Germans knew that gospel, too. They had their own sniper manuals. They’d read captured Soviet ones. They’d seen these patterns play out in Poland, in France, in the Baltics.

If you followed the rules, you were predictable.

If you were predictable, you were dead.

Lyudmila started doing something dangerous:

She thought for herself.

She studied every failed engagement she survived.

Pattern:

-

Soviet sniper takes a good position.

Takes a shot.

Germans triangulate.

Counter-sniper or artillery reacts.

Soviet sniper dies or flees.

They weren’t losing because they couldn’t shoot. Soviet snipers were excellent marksmen. They were losing because they were always reacting, never initiating. Always defending, never hunting.

German snipers like Becker did the opposite. They forced you to move, then killed you when you did.

Lyudmila decided to flip the game.

She’d make the Germans react to her.

Which meant breaking every rule she’d been taught.

Her trick was simple and suicidal:

She exposed herself.

On purpose.

Not fully, not stupidly. Carefully. Designed.

She built two hides, not one. Primary and secondary, but unusually close—just four to six meters apart.

In the primary nest, she put a decoy: a helmet on a stick, a spare sleeve stuffed with straw, sometimes just a shadow shaped like a head and shoulders. From 300+ meters away through a scope, it looked like a real sniper.

She hid in the secondary nest. Concealed. Rifle ready.

Then she waited.

Sooner or later, a German counter sniper would see the decoy and shoot. He had to. A Soviet sniper in the open was too juicy a target.

The moment he fired, the game changed.

Muzzle flashes are hard to hide, especially in low light. Through her scope from the secondary nest, Lyudmila would see that flash. She had maybe two to four seconds before the German realized he’d hit straw instead of flesh and started moving.

Two to four seconds to:

Find him.

Adjust for distance and wind.

Fire.

If she missed, he’d know her real position. Then it was her turn to be hunted.

If she hit, she moved. Immediately. Tear down, relocate, repeat.

It broke doctrine.

Doctrine said, “Never expose a position, even a fake one.”

Doctrine said, “Survival is concealment.”

Lyudmila decided survival was aggression.

September 3rd, 1941.

She tested it.

Early morning, German lines 340 meters away. She set up in a ruined cellar: two nests, one decoy. Helmet propped just where a sniper might peek.

Then she melted into the secondary nest, five meters to the right, rifle aimed at the most likely German counter-position.

Forty-five minutes of nothing.

Insects crawling on her hands.

Back screaming from stillness.

Then: a crack. The helmet exploded off the decoy.

Muzzle flash, 320 meters, behind a shattered brick wall.

Three seconds.

She didn’t think. She just did what training and months of rage taught her.

Adjust. Squeeze.

The figure dropped.

She didn’t wait for confirmation. She crawled to a third position, set up again, watched.

A little later, two Germans crawled to the wall and dragged a body back.

First hunter down.

Over the next six weeks, Lyudmila refined the trap.

She learned:

German snipers preferred upper floors.

Avoided ground-level holes.

Used the sun at their backs.

Hated moving in daylight.

So she set her decoys where they liked to look and hid where they least expected.

By October, she had 78 confirmed kills.

Twenty-two were snipers.

Word spread along the Soviet line:

“There’s a girl who hunts the Germans who hunt us.”

Soldiers began requesting her by name when a sniper problem got bad.

Officers who’d watched their men picked off one by one came to her, hat in hand, asking for help.

Sometimes they brought vodka.

Sometimes extra bread.

Often just grief.

The duel that turned her into legend came at Sevastopol.

November 1941.

German forces pressed the city hard. The siege was brutal—bombardments, hunger, horses butchered for food.

And somewhere beyond the rubble, a German sniper was surgically dismantling Soviet command.

In three days, he killed:

Eleven Soviet officers and NCOs,

Always at dawn,

Always one shot, one kill.

He never stayed in the same place. He never fired twice from the same angle.

He was, in every sense, perfect.

Soviet officers stopped standing up.

Sergeants refused to cross open ground.

The unit started to fall apart.

Major Chernov brought Lyudmila into HQ, showed her the bodies, the impact charts.

“We don’t move in the daytime anymore,” he said. “We can’t. He kills anyone who gives an order.”

They gave her 48 hours.

Find him. Kill him. Or this sector breaks.

She walked the perimeter with a reconnaissance officer named Boris. Together they mapped angles, lines of fire, escape paths.

Fourteen positions could have produced the kill angles they saw.

Fourteen was too many.

She needed to make him choose. To force him to shoot at her.

So she put on a dead lieutenant’s greatcoat and walked into the open.

No decoy.

No straw.

Just Lyudmila standing where an officer would stand for a morning briefing.

Her real nest was four meters away, rifle trained at the most likely tower ruin.

She stood there in the cold.

Seventeen minutes.

Every second, her skin crawled, expecting a bullet.

Nothing.

Maybe he wasn’t there.

Maybe he was watching and laughing.

Maybe he was just better than she was.

At 5:59 a.m., the shot came.

A Mauser crack. The bullet missed her head by centimeters. She felt its slipstream.

She dove toward the rifle, not away from the shot.

Hands on wood. Cheek on stock. Eye in the scope.

Muzzle flash – third floor of a ruined church tower, 300 meters.

He was moving back into shadow. She had no time for perfect math.

She fired on instinct.

The figure staggered. Fell.

She stayed down. Waited. Watched.

No second shot.

Infantry moved on the position. Cleared the tower.

Boris leaned out of the shattered bell opening, waved his arms.

“Got him! He’s dead!”

They found a highly modified rifle, personal log book, 60-plus confirmed kills. Whether his name was truly König, as later propaganda claimed, or someone else, doesn’t matter.

He was good.

He was hunting them.

She hunted him better.

And she did it by using herself as bait.

Between August 1941 and May 1942, Lyudmila Pavlichenko recorded 309 confirmed kills:

36 snipers,

187 officers and NCOs,

The rest machine-gunners, spotters, infantry.

Every single kill was logged, witnessed, confirmed. Soviet command had to be strict. They needed real heroes, not invented ones.

She was wounded four times.

The last wound – mortar shrapnel to the face – finally pulled her off the line.

Not because she wanted to go. Because Moscow decided the woman with 309 kills was more valuable alive as a symbol than dead in a crater.

They made her a Hero of the Soviet Union.

They sent her to Moscow, then London, then Washington.

She hated it.

She wanted her rifle back.

Instead, she shook hands with Churchill, had tea with Eleanor Roosevelt, and stood on American stages telling crowds:

“Gentlemen, I am 25 years old and I have killed 309 fascist occupants. Don’t you think, gentlemen, you have been hiding behind my back too long?”

Crowds roared.

Propaganda loved it.

But behind every number, every speech, were those six-hour days in the ruins, those insane gambles with her life.

Those dual nests.

Those decoys.

Those seconds where everything could go wrong.

After the war, she trained snipers instead of being one. Passed on her tricks.

Her aggression, her bait tactics, her “hunt the hunter” mindset seeped into doctrine. Today, modern snipers around the world use versions of her methods without knowing her name.

Ask most people about Pavlichenko, if they know her at all, and you’ll hear:

“The Soviet girl sniper with 309 kills.”

That’s the headline.

The truth is deeper.

She wasn’t just “good with a rifle.”

She looked at the rules everyone followed and realized those rules were getting them killed.

She broke them.

She survived.

And she changed how a whole profession fights.

We celebrate heroes who follow orders.

We should make more room for the ones who don’t — when the orders are wrong.

Lyudmila Pavlichenko used herself as bait to kill the hunters.

Now you know her story.

If this hit you the way it hits us, tap like so more people see it.

Tell us where you’re watching from.

And if you want more stories about real people who changed the war by thinking differently, hit subscribe.

The people who lived this deserve to be remembered.

The end.

News

(CH1) Admirals Called Her Chalk Trick “STUPID” – Then It Saved 48,000 Lives

At 6:43 on a raw March morning in 1943, a nineteen-year-old woman stood in a cold Liverpool basement and looked…

(CH1) How One Girl’s “SILLY” Chalk Trick Made German U-Boats Sink 3 Times Faster

At 6:43 on a cold Liverpool morning in March 1943, a nineteen-year-old woman stood in the middle of a painted…

(CH1) How One 14-Year-Old Girl’s “Crazy” Bicycle Trick Killed Nazi Officers

In the history of warfare, death usually wears a uniform. It arrives with the thunder of artillery, the scream of…

(CH1) How One US Woman’s “Shopping Trips” Saved 7,000 Allied Pilots from Nazi Prisons

March 2nd, 1943. Marseille. The coded telegram was short, cold, and devastating. “Pat has fallen.” Four hundred kilometers away, in…

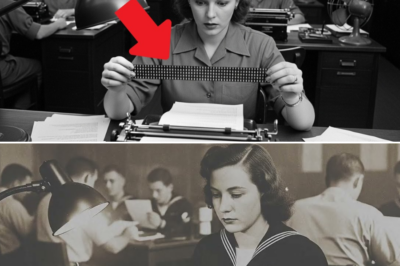

(CH1) How One American Woman’s Torn Typewriter Ribbon Saved 3,000 Lives and Sank 4 Japanese Carriers in 5 Hours

At 4:17 a.m. on May 25th, 1942, the ocean was still dark outside Honolulu, but inside the Fleet Radio Unit…

(Ch1) How One Woman’s Bicycle Chain Silenced 50 German Tanks in a Single Morning — And No One Knew

At 5:42 a.m. on October 3rd, 1943, the gray morning light slid across Hall 7 of the Henschel & Sohn…

End of content

No more pages to load