At 6:43 on a cold Liverpool morning in March 1943, a nineteen-year-old woman stood in the middle of a painted floor, looking down at a sea that existed only in chalk.

The floor in the basement of Derby House was linoleum, but in the minds of everyone working there it was the North Atlantic. Rectangles of wood marked convoys of merchant ships. Small white blocks marked escort destroyers. Black blocks marked German U-boats. When the black blocks slid between the white ones, the red counters came out. Red meant ships sunk. Red meant men drowned.

Her name was Janet Patricia Oake, and she had just run a simulation that exactly matched the real-world convoy massacre which, two days earlier, had killed her brother.

The telegram about HMS Hesperus had arrived while she was still in “the pit,” as they called the tactical floor. She read it in the harsh electric light of the Western Approaches Tactical Unit – WATU – where the war at sea was being fought in numbers and chalk. “Lost with all hands.” There was no room for euphemism in that phrase. Her brother Thomas, twenty-three years old, an anti-submarine warfare officer, was gone.

He had written to her weeks earlier from that very destroyer, escorting a convoy across the Atlantic. The tactics aren’t working anymore, he had said. They chased the U-boats, dropped depth charges where they thought they might be, and still the ships died. His words had the frustrated edge of a professional who knew something was wrong but could not quite explain it.

Janet had spent eight months at WATU doing exactly what he could not: explaining why the escorts kept failing.

It was an unlikely posting. When she had joined the Women’s Royal Naval Service straight from school in 1942, she had been a promising mathematics student, not a mariner. Her skills lay with algebra and geometry, not charts and compasses. But the Royal Navy had a problem it could not ignore. The Battle of the Atlantic – the lifeline that kept Britain fed and fuelled – was going badly.

For years, convoy after convoy had been savaged by German U-boats operating in wolfpacks. Escort commanders, schooled in two centuries of British naval tradition, did what doctrine demanded: they hunted the enemy aggressively. When a submarine was spotted or its presence betrayed by a torpedo, destroyers broke from the convoy screen and charged off to attack. On the surface that seemed brave, Nelsonian even. In practice, it was an invitation to disaster.

By the summer of 1942 the Admiralty grudgingly agreed to support a strange experiment in a basement under Liverpool: a tactical laboratory run by Captain Gilbert Roberts, a tuberculosis-scarred officer declared unfit for sea. Roberts had been given three things: a blank floor, a handful of bright young Wren telegraphists with no pre-war naval experience, and orders to “find out how to beat the U-boats.”

The Western Approaches Tactical Unit was born there on that linoleum.

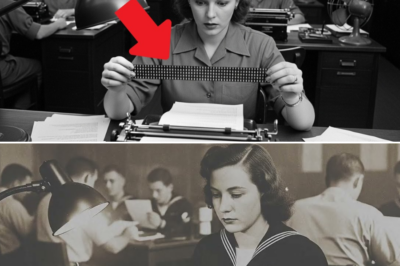

The method was deceptively simple. Officers fresh from escort duty were brought down into the basement and invited to command their convoys in a war game, seeing their actions play out in miniature. The Wrens, including Janet, took the role of the enemy, moving the black U-boat blocks across the painted grid according to real German tactics gleaned from intercepted signals and captured documents. Every movement was timed on stopwatches. Every course change and attack run was recorded.

When Janet took charge of the U-boats for the first time, she approached the problem the way she approached an equation. She looked for pattern and consequence, for the chain of cause and effect that doctrine blurred beneath phrases like “offensive spirit” and “initiative.” The pattern emerged quickly. When escorts stayed close to the convoy, keeping their screen tight, the U-boats struggled to get in and line up torpedo shots. When one submarine broke the surface and was seen, and the escorts hurtled after it in a fury of star shells and depth charges, a gap opened where they had been. Other submarines slipped through those gaps. Red counters began to litter the floor.

Again and again, officers at the plotting table made the same choices their doctrine demanded. Again and again, Janet’s wolfpack exploited them. Convoys died not in spite of experienced leadership, but because of it.

The sinking of Convoy SC 121 in late February 1943 was a brutal confirmation. Fifty-nine merchant ships had left Nova Scotia eastbound, guarded by nine destroyers. The U-boats found them mid-ocean and attacked at night. By the time it was over, thirteen of those merchants were burning or sinking, and HMS Hesperus, Thomas’s ship, lay on the bottom with all hands after taking a torpedo while racing to attack a submarine that had already slipped away.

Janet read those details in the official report even as she stood amid the chalk tracks of her own simulation of the same convoy. She had run the scenario beforehand. She had seen, in miniature, how escorts charging off after U-boats would allow other submarines to punch through the weakened screen. Her mathematical conclusion, written in tidy script in Captain Roberts’ reports to the Admiralty, had been stark: aggressive pursuit was creating vulnerability. The more escorts hunted, the more they left their convoys exposed.

Those reports had gone largely unheeded. War is conservative by nature. The Royal Navy had been built on the creed that offense wins battles. To suggest that in the submarine war defense – bare, unromantic defensive discipline – might be the key to survival was to attack not just tactics but a culture.

Janet’s grief hardened into resolve. Two days after the telegram, she asked Roberts for what amounted to an audience with the most powerful man in Western Approaches Command.

The admiral in question, Sir Max Horton, was no armchair sailor. In the First World War he had commanded submarines himself, stalking German shipping in the North Sea. He understood the hunter’s mindset intimately. Now, in 1943, he was the man responsible for every convoy crossing the Atlantic.

Horton had heard about WATU and its floor games in the abstract, and he was intrigued enough to visit Derby House. Captain Roberts greeted him and, with all the diplomatic caution he could muster, invited him not to sit in a corner and observe, but to take command of the escort group in one of their simulations.

The admiral agreed.

Janet and her fellow Wren, Jean Laidlaw, laid out the scenario: a mid-Atlantic convoy under winter conditions, fifty merchant ships with eight escorts. U-boats waited in the murk beyond. Horton stood on the balcony overlooking the painted sea, studying the layout as though it were a real operations room. When he was satisfied, he deployed his destroyers in the way his decades of experience prescribed – spread out, forming a wide ring, ready to spring at any sign of a submarine.

From her position in the “enemy” chair, Janet watched those white blocks slide into their familiar hunting pattern and felt a grim sense of déjà vu.

At the start, she moved one U-boat brazenly close, just far enough that one escort’s sonar “contact” could justify a surge. Horton reacted as any of his escorts would have reacted in the Atlantic: two destroyers leapt from the ring, like hounds off the leash, charging toward the threat. Depth charges “rolled,” chalk marks etched the sea with their patterns. For several minutes Horton focused on the chase.

That was the moment Janet had been waiting for. While those two escorts were away, she moved her remaining U-boats into the gap they had left. Jean did the same on the other side. Now inside the broken circle, the black blocks turned inward and moved among the merchants.

Red markers began to pile up. The admiral tried to pull his ships back to plug the hole, but the damage was done. Within forty-seven minutes of game time, seventeen of his merchant ships were destroyed. Not a single U-boat had been sunk.

No one spoke at first. Senior officers watching from the edge of the pit avoided eye contact. Roberts kept his face neutral. Janet, chalk in hand, waited. With a single sentence Horton could have dismissed the whole exercise as an academic trick. He could have laughed, thanked them, and gone back to fighting the war the way he always had.

Instead, he did what great commanders, and good scientists, do when the data hurt: he changed his mind.

“This works,” he said quietly. “Teach every commander.”

Those words were Janet’s victory, though she took no joy in them. They had come too late for Thomas, and for dozens of convoys gone before. But from that day on, WATU was transformed from an eccentric annex into the beating tactical heart of the Atlantic war.

Over the next months, steady streams of officers from escort groups across the Allied navies descended into the basement where the nineteen-year-old waited for them with chalk and a wolfpack. Some came with open minds, stunned by Horton’s endorsement. Others arrived resentful, older men bristling at the idea that Wrens with no sea time were to instruct them in the art of naval warfare.

The pit levelled those differences. Time after time, Janet and her colleagues allowed the visiting commanders to deploy their escorts however they wished and then used German tactics to test those choices to destruction. The pattern repeated: doctrines built for gunnery duels against visible ships faltered against the mathematics of invisible predators.

Again and again, the lesson emerged: when an escort abandoned its place to chase a submarine, the system failed.

From the wreckage of those games, new doctrine was born. Tactics were given names to make them memorable: Raspberry, a drill in which escorts lit up the night with star shells to deny U-boats the cover of darkness; Beta Search, a search pattern based on predicted U-boat behavior rather than hopeful sweeping of empty ocean; Pineapple, a method of keeping the screen intact under multi-directional attack; Step Aside, a maneuver to throw off the primitive acoustic torpedoes that homed on propeller noise.

At their core, all these innovations prized discipline over dash, cohesion over individual hunting glory. The convoy was no longer bait to draw the enemy into a fight. It was the thing itself, the bloodstream of the nation, to be encircled and guarded at all costs.

By May 1943, as the first cohorts of WATU-trained officers took command at sea, the statistics shifted dramatically. That month, German Admiral Karl Dönitz would later write, was “Black May” for the U-boat fleet. Forty-one submarines were sunk. Loss rates for merchant shipping, which had hovered at catastrophic levels through the winter, plunged. Convoys began to reach Britain intact. The long-sought control of the sea lanes was finally within reach.

Historians would later tally the effects of the tactical revolution that began on that basement floor and estimate that thousands of ships and tens of thousands of sailors survived the Atlantic war because of it. In the contemporary moment, few of those sailors ever knew that their lives had been wagered and saved in a room they would never see.

Janet stayed at WATU until the end of the war, training more than 5,000 officers in the new doctrine, running 473 separate simulations by one tally. She did not go to sea. Her ocean remained that painted linoleum, her ships the blocks she moved across it with the precision of someone playing both sides of a chessboard.

When peace finally came, the secrets of Western Approaches Tactical Unit were sealed. The young women who had taught admirals to rethink Nelson were bound by the Official Secrets Act to say nothing. Janet left the Navy, married, and became a mathematics teacher. On her CV, under “War Service,” she could write only a vague line: “Operations, WRNS.”

For decades, the historiography of the Battle of the Atlantic focused on machines and grand strategy: the codebreaking triumphs at Bletchley Park, the advent of centimetric radar, the appearance of escort carriers. Commanders and scientists were named and lauded. The pit and its chalk gathered dust in the archives.

Only in old age did Janet begin to talk about it, and even then she tended to deflect credit. It was a team, she insisted. Captain Roberts deserved the lion’s share. That may have been true, but the officers who had stood in the pit with her remembered the young Wren who had calmly, repeatedly sunk their convoys until they learned not to abandon them.

Janet Oake died in 2009. Her obituary in the national press mentioned her war service in passing, without detail. The tactical drills she helped devise, refined and taught, lived on in naval textbooks and training syllabi with the names WATU had given them, but not with hers.

If you go now to the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich, there is a small exhibit about the Western Approaches Tactical Unit. In one of the photographs a slight young woman stands by the edge of the painted sea, chalk between her fingers, eyes level with the camera. The caption lists her as a Wren.

It does not say that she walked into a room full of senior officers and, two days after her brother’s death, forced them to look at the cold arithmetic of their failures. It does not say she spoke for the men whose names appear only on telegrams.

But you know it now.

When the Battle of the Atlantic turned, it did so not just on the bridge wings of destroyers bucking through the gray Atlantic swell, but also on a chalk-stained floor under Liverpool, where a nineteen-year-old mathematician, armed with nothing more than pattern recognition and stubborn moral courage, decided that being right on paper was not enough. Someone had to make the Admiralty listen.

News

(CH1) Admirals Called Her Chalk Trick “STUPID” – Then It Saved 48,000 Lives

At 6:43 on a raw March morning in 1943, a nineteen-year-old woman stood in a cold Liverpool basement and looked…

(CH1) How One 14-Year-Old Girl’s “Crazy” Bicycle Trick Killed Nazi Officers

In the history of warfare, death usually wears a uniform. It arrives with the thunder of artillery, the scream of…

(CH1) How One US Woman’s “Shopping Trips” Saved 7,000 Allied Pilots from Nazi Prisons

March 2nd, 1943. Marseille. The coded telegram was short, cold, and devastating. “Pat has fallen.” Four hundred kilometers away, in…

(CH1) How One American Woman’s Torn Typewriter Ribbon Saved 3,000 Lives and Sank 4 Japanese Carriers in 5 Hours

At 4:17 a.m. on May 25th, 1942, the ocean was still dark outside Honolulu, but inside the Fleet Radio Unit…

(CH1) How One Female Sniper’s “CRAZY” Trick Took Down 309 Germans in Just 11 Months

5:47 a.m. – August 8th, 1941. Belaya Tserkov, Ukraine. Twenty-four-year-old history student Lyudmila Pavlichenko crouched behind a pile of shattered…

(Ch1) How One Woman’s Bicycle Chain Silenced 50 German Tanks in a Single Morning — And No One Knew

At 5:42 a.m. on October 3rd, 1943, the gray morning light slid across Hall 7 of the Henschel & Sohn…

End of content

No more pages to load