March 2nd, 1943. Marseille.

The coded telegram was short, cold, and devastating.

“Pat has fallen.”

Four hundred kilometers away, in a cramped apartment in Toulouse, an elderly woman unfolded the message with hands that didn’t shake.

In Marseille, Belgian doctor Albert Guérisse—known in the underground as Pat O’Leary—sat in a Gestapo interrogation room, his face already swollen from the first round of questioning. In the cells below, 47 more resistance workers waited for the same treatment. The largest escape network in occupied France was collapsing in real time.

Over 600 Allied airmen had already escaped through the O’Leary Line: downed pilots and crew shepherded from Belgium through France to Spain. Now, in 72 hours, one British traitor and one Gestapo roundup had destroyed it.

What the Gestapo did not know was that the woman reading that telegram in Toulouse—a 61-year-old dressmaker with a cat on her lap and a cigarette in her ivory holder—was about to do something they believed impossible.

At that moment, 127 Allied airmen were hiding in barns, attics, and cellars across southern France. Without the O’Leary Line, they were stranded behind enemy lines. German patrols were tightening their search. Every hour increased the odds of capture.

In London, this was more than a moral crisis. It was arithmetic.

Training a single B-17 bomber crew cost roughly $150,000 in 1943 dollars and three months of intensive instruction. Each crew carried ten highly trained specialists. In 1943, fewer than one in four bomber crews survived their full 25-mission tour. Losing men wasn’t just tragic. It was strategically unsustainable.

Downed airmen who survived the crash and evaded immediate capture represented a massive investment in training, experience, and morale. When they were caught, that investment vanished behind barbed wire.

The O’Leary Line had been the answer: an underground railroad stretching from Brussels to the Spanish border. But it had a fatal flaw.

It depended on one man.

When that man fell, London wrote the network off as lost.

In Toulouse, Marie-Louise Dissard read the telegram, dropped it into the fireplace, and reached for her handbag. Inside: fake identity cards, 50,000 francs in MI9 money, and the addresses of eighteen men wanted by the Gestapo.

She had perhaps 48 hours before they came for her.

She decided not to run.

“Francoise” in Plain Sight

Marie-Louise Dissard did not look like anyone’s idea of a resistance leader.

Born in 1881 in Cahors, she was 61 when the war came fully to southern France. She ran a small dressmaking shop on the Rue du Palmier in Toulouse and worked part-time as a secretary at city hall. She was small, sharp-spoken, always smoking, always carrying a shopping basket. The local police file on her described her as eccentric and “possibly unbalanced.”

Which suited her perfectly.

Her entry into the underground began in July 1942, when a man from the O’Leary Line named Paul Ullmann knocked on her door. He needed safe lodgings for downed airmen. Her modest means and her reputation made her ideal.

“How many?” she asked.

“Six. For now,” he replied. “There will be more.”

She looked around her small apartment, at her dress shop below, at her ordinary life.

“All right,” she said. “Bring them.”

Within months, she was cooking meals for resistance fighters, renting extra rooms, and escorting airmen across the city under layers of lies and charm. Her code name was Françoise.

She noticed something that neither British intelligence nor German counter-intelligence grasped:

No one looks twice at an old woman with a shopping basket.

When the O’Leary Line Fell

On March 2nd, 1943, Harold Cole—a British sergeant who sold out his own side to the highest bidder—completed his treachery.

He gave the Gestapo the addresses, names, methods, and safe houses of the O’Leary Line.

In 48 hours, the Germans rolled up the network: guides, forgers, safe house keepers, even sympathetic train conductors. Albert Guérisse was captured. So were dozens of helpers. The southbound escape pipeline was shredded.

Across the countryside, airmen who’d been promised evacuation suddenly had nowhere to go.

In London, MI9 officer Airey Neave scrawled in his diary: “We are back to zero. Any airman going down now is lost.”

In Toulouse, Marie-Louise read “Pat has fallen” and understood exactly what that meant.

One hundred twenty-seven airmen: stranded.

Gestapo: hunting.

British: blind.

Most people in her position would vanish into the countryside.

Instead, she opened her window, let the telegram burn to ash, picked up her cat, slipped on an absurd hat, and walked straight toward the Gestapo.

Not into their office, but into the apartment building next door.

She rented a flat.

“They’ll never look for me where they sleep,” she joked later. “I hid under their nose.”

From that apartment, within earshot of German boots, she began rebuilding the network the Allies had written off.

The Françoise Line

The principle of her new system was simple and insane.

Downed airmen would be collected by local farmers and resistance contacts.

Word would reach Toulouse.

Françoise would arrange identity papers and train tickets.

Then she would personally escort the airmen past German checkpoints as her “nephews.”

A young man in ill-fitting French clothes with poor French was suspicious. A shy “nephew” accompanied by an over-talkative, chain-smoking aunt fussing with her cat and basket was ordinary.

The Germans saw what they expected to see.

Her first major test came in April 1943: eight American airmen hiding near Bergerac with Gestapo sweeps closing in. Over four days, she made three trips, each time shepherding two or three airmen through checkpoints by sheer force of personality.

She talked at guards. She argued about ration cards. She complained about the cold. Soldiers stamped her papers quickly just to make her go away.

All eight airmen reached Toulouse.

From there, she passed them on along forged identities, through Perpignan, over the Pyrenees, and into Spain.

When she reported the success to fellow resistance members, they were horrified.

“This is suicide,” one told her. “You’re loud. You’re visible. You’re memorable.”

“Exactly,” she replied. “They remember me. They don’t remember the men.”

London Argues. London Relents.

News of the “Françoise Line” reached London via a British vice-consul in Switzerland.

The reaction at MI9 was mixed.

On paper, the new network was reckless:

– No formal dead-drops.

– No secure radio traffic.

– No professional tradecraft.

– One elderly woman at its center.

“We can’t build a system around someone like this,” one officer objected. “It’s worse than O’Leary. If she’s caught, everything goes again.”

But the numbers were already arguing for her.

Since O’Leary’s arrest, official networks had evacuated no one from that sector.

This unknown seamstress had moved 34 men in six weeks.

A senior officer cut through the debate: “From March to now, how many evaders did our trained networks extract from southern France?” Silence. “And how many did this woman get out?” More silence.

He nodded. “We don’t have to like her methods. We have to recognize they work.”

MI9 not only approved funding—they gave her operational independence.

Airey Neave added one hard instruction to his file: “For God’s sake, don’t tell her how to do her job.”

Hiding in Plain Sight

By late 1943, the Françoise Line had grown into a web across southern France. Her network included:

Train conductors who “lost” tickets,

Farmers who hid airmen in haylofts,

Doctors who certified false illnesses,

A few priests and nuns who offered sanctuary,

And even several French policemen who quietly looked the other way.

All of it coordinated from an apartment pressed up against Gestapo headquarters.

German intelligence knew evaders were still getting out of the Toulouse sector. They could see it in their statistics. But their reports show how badly they misread the source.

One Gestapo memo, recovered after the war, reads:

“Continued escapes of Allied airmen through Toulouse region. Suspected Communist rural network. Increased surveillance of countryside recommended.”

They were watching the hills.

The danger lived in town.

Another report notes an “elderly woman frequently seen escorting young men on trains to Perpignan” and identifies her as “Marie-Louise Dissard, age 62, dressmaker, reputed eccentric, mentally unstable. Assessment: harmless. No action required.”

During that same period, she moved 43 airmen past German inspections.

The mask worked.

The Stakes: Men, Money, and Time

To grasp what she accomplished, it’s worth looking at the cold math again.

When a heavy bomber went down over France:

A crew of ten died or fell into captivity.

Their training—about $15,000 per man in wartime dollars—was lost.

Their hard-won combat experience—dozens of missions—disappeared.

The replacement crew took months to train and had no experience.

Escape lines like O’Leary and Francoise changed that calculus.

Of the men who survived a crash:

30–40% evaded immediate capture.

In areas with functioning escape lines, 60–70% of those evaders eventually made it back to Allied control.

Those returnees didn’t go home. They went back to their squadrons, bringing:

Firsthand intelligence on flak concentrations, fighter tactics, and targets.

Combat experience that made them steadier and more effective.

Morale: proof to other crews that if they went down, someone might bring them back.

Every man Marie-Louise escorted wasn’t just a life saved. He was a multiplier for the Allied air campaign.

Risk Without Pause

In January 1944, one of her guides was arrested in Perpignan. In his notebook, the Gestapo found an address in Toulouse.

Hers.

She cleared her safe houses in 24 hours, moving nine fugitives to new hiding places—barns, attics, back rooms of sympathetic business owners. Then she vanished.

For six months, she lived in the shadows of her own city. Sleeping in different apartments each week. Eating when she could. Still running the line. Still riding trains. Still carrying that basket, dressed sometimes so plainly she blended into stone, other times so ostentatiously that no one took her seriously.

A policeman later said, “She was everywhere and nowhere. We thought she’d been arrested. Then she’d appear with a new airman and a new story for the checkpoint.”

By early summer 1944, the net was tightening. Allied invasions in Normandy and preparations for Operation Dragoon in the south brought more patrols, more checkpoints, more crackdowns.

She responded the only way she knew how: by pressing harder.

Her last major operation before liberation involved eight American airmen to be moved from Toulouse to Perpignan in July 1944. The line through the Pyrenees was barely functioning; patrols had increased.

She escorted them to the train herself.

Later, one of those airmen recalled:

“I thought we were doomed. There were Germans everywhere. And this old lady just fussed over us, fixed our collars, complained to the soldiers about the draft from the train window. They stamped our papers without even looking at my face.”

All eight made it to Spain. Two weeks later, Allied troops landed in southern France.

The occupation was ending.

Aftermath and Obscurity

Toulouse was liberated in August 1944.

By then, Marie-Louise was exhausted. She had spent the last two years living on cigarettes, black coffee, and adrenaline, making decisions hourly that could kill or save people.

The new French authorities and the returning Allies wanted heroes.

They found her.

France awarded her the Légion d’Honneur and the Croix de Guerre. Britain gave her the George Medal. The United States presented her with the Medal of Freedom with Gold Palm. Belgium honored her as well.

At one ceremony, when an American general pinned the Medal of Freedom to her dress and called her a “great heroine of the underground,” she said quietly into the microphone:

“This belongs to the ones who didn’t come home. I merely walked and talked.”

After the war, she went back to her shop. She had no taste for politics, declined to run for office, and refused to write a memoir. She lived simply in Toulouse until her death in 1957 at the age of 75.

Most of the roughly 700 airmen she helped save never learned her full story. To them, she was “Françoise,” the old lady with the cat and the endless cigarette, who somehow ghosts them under the noses of the Gestapo and onto a path home.

In Toulouse today, a street bears her name. A modest cultural center is dedicated to her memory. In archives in London and Washington, she’s a file, a codename, some numbers.

But the numbers are worth remembering:

~700 airmen shepherded to safety across her O’Leary and Françoise years.

Thousands of combat hours returned to Allied squadrons.

Untold lives downstream—families, children, grandchildren—that exist because a woman everyone underestimated refused to leave men stranded.

Airey Neave, the British MI9 officer who approved her funding, summed it up in his memoir:

“The war was won by people like Marie-Louise Dissard. Ordinary people who did extraordinary things because someone had to.”

The Gestapo thought she was a harmless, annoying old shopkeeper.

She was, in fact, one of the most effective resistance organizers in occupied Europe.

If there’s a thread tying together all these forgotten stories—the snipers, the codereakers, the cooks, and the seamstresses—it’s this:

The war’s outcome didn’t just hinge on generals’ plans.

It hinged on people nobody expected.

People like Marie-Louise, with a shopping basket and a stubborn refusal to accept that nothing could be done.

News

(CH1) Admirals Called Her Chalk Trick “STUPID” – Then It Saved 48,000 Lives

At 6:43 on a raw March morning in 1943, a nineteen-year-old woman stood in a cold Liverpool basement and looked…

(CH1) How One Girl’s “SILLY” Chalk Trick Made German U-Boats Sink 3 Times Faster

At 6:43 on a cold Liverpool morning in March 1943, a nineteen-year-old woman stood in the middle of a painted…

(CH1) How One 14-Year-Old Girl’s “Crazy” Bicycle Trick Killed Nazi Officers

In the history of warfare, death usually wears a uniform. It arrives with the thunder of artillery, the scream of…

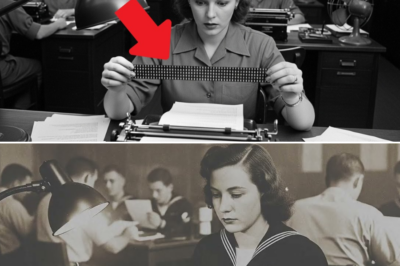

(CH1) How One American Woman’s Torn Typewriter Ribbon Saved 3,000 Lives and Sank 4 Japanese Carriers in 5 Hours

At 4:17 a.m. on May 25th, 1942, the ocean was still dark outside Honolulu, but inside the Fleet Radio Unit…

(CH1) How One Female Sniper’s “CRAZY” Trick Took Down 309 Germans in Just 11 Months

5:47 a.m. – August 8th, 1941. Belaya Tserkov, Ukraine. Twenty-four-year-old history student Lyudmila Pavlichenko crouched behind a pile of shattered…

(Ch1) How One Woman’s Bicycle Chain Silenced 50 German Tanks in a Single Morning — And No One Knew

At 5:42 a.m. on October 3rd, 1943, the gray morning light slid across Hall 7 of the Henschel & Sohn…

End of content

No more pages to load