At 5:42 a.m. on October 3rd, 1943, the gray morning light slid across Hall 7 of the Henschel & Sohn tank plant in Kassel.

Rows of brand-new Panzer IVs and Tigers stood in formation on the assembly floor, steel hulls still smelling of fresh paint and hot welds. Overhead, lamps buzzed, casting cold light over the final line.

According to the shift plan, by 6:00 a.m. every engine should have been running, oil lines pressurized, transmissions engaged. Twenty tanks were scheduled to roll toward the rail yard before breakfast.

Instead, nothing happened.

The air was thick with machine oil and iron dust, but not a single motor turned.

Foremen climbed into turrets, turned ignition keys, and shoved throttles forward. Engines coughed, clattered, tried to bite. Then, one after another, they stalled.

Every gearbox on the line had locked solid.

Somewhere down on the floor, a mechanic swore. Sparks flew from overloaded testing rigs as operators tried again and again, until the chief of production shouted for everything to be shut down.

Within minutes, the hall filled with shouting. It wasn’t usual factory noise—a dropped wrench here, a jammed press there. This was panic. The panic of something impossible.

From the second-floor observation deck, an officer in a black Panzer uniform looked down at fifty dead tanks. He watched the frantic gestures, the technicians tearing open access panels.

“Sabotage.”

He didn’t raise his voice. He didn’t have to. No one dared agree out loud. But 50 tanks destined for the Eastern Front—an entire week’s output—had just become 45 tons of useless steel each.

Somewhere deep in that mechanical labyrinth, something microscopic had broken the war machine.

Outside the gates, a thin woman in a dark coat pedaled away on a rusted bicycle.

Her name was Lotte Bäuer. Twenty-nine years old. Maintenance mechanic, gearbox section, night shift.

Her bicycle tires hissed over wet cobblestones. The cold air stung her cheeks. In the small canvas pouch on her handlebars, she carried half a loaf of bread, a wrench, and a short length of chain.

Nothing unusual for a worker going home at dawn.

What nobody in Kassel knew that morning—not the supervisors, not the guards, not the officers who would spend the next weeks tearing their factory apart—was that the chain in her bag didn’t belong to her bicycle.

It belonged to history.

In 1943, Henschel & Sohn in Kassel was one of the beating hearts of the Reich’s armored power.

Assembly halls stretched nearly a mile along the Fulda River. Every day, trains brought steel plate from Essen, Maybach engines, gear assemblies from Ruhr workshops. Inside, 12,000 men and women labored under the never-ending rhythm of war.

The sound was constant: riveters hammering, cranes screeching, welders throwing blue sparks across the floor. It wasn’t just industry. It was the pulse of the Eastern Front.

The plant produced roughly thirty-five tanks a week. A Panzer IV’s transmission alone required 140 individual parts, every one tracked by serial number and inspected. A Tiger needed even more—200,000 individual components, 500 man-hours of machining, and twelve separate sub-lines feeding the final assembly.

On paper, nothing in that system was allowed to go wrong.

On the floor, everything depended on people like Lotte.

Officially, she was “Mechanikerin, Wartung – Getriebebau, Schicht C.” Maintenance tech, gearbox section, night shift. Unmarried. No party membership on file. Good record. Quiet.

Before the war, she had repaired bicycles in her father’s shop near Stuttgart and done a little amateur racing. That’s where she learned to feel a bearing through her fingertips, to hear when a chain was too tight just by listening to the click under load. She spoke in metal: slack, tension, misalignment.

The men called her “das Mädchen mit den leisen Händen” — the girl with the quiet hands. She rarely spoke. She never made mistakes.

Her station sat next to the final gearbox inspection bench, where teams tested the transmissions before they were bolted into tanks. Each gearbox weighed nearly 600 kilos, a dense maze of shafts, gears, and a chain that linked the main drive to the clutch assembly.

The tolerances were microscopic. A misalignment smaller than a millimeter could seize the entire unit.

Lotte’s job was to keep that from happening.

Twelve-hour nights under dimmed lights—air-raid precautions meant the factory never operated at full brightness after dark. Welding arcs and press rams punched holes into the shadows. One third of the workers around her were foreign forced laborers: Poles, Czechs, Frenchmen in gray coveralls marked with colored patches that told you who was allowed to live where.

To the guards, they were invisible. To each other, they were something else: witnesses.

A Polish mechanic once slid Lotte a piece of bread when she fainted from hunger at her post. She hid a file for another man caught with tools he shouldn’t have had. He was hanged in the courtyard two days later.

That was when something in her shifted.

She stopped believing in victory long before Berlin admitted the possibility of defeat.

She watched the machines differently. Not as a loyal worker, but as a saboteur in training. She watched how a jammed gearbox could stall the entire line. How supervisors panicked under pressure and signed off on work they hadn’t checked. How the system’s strength depended on a single fragile thing: obedience.

One deviation, one invisible flaw, and the whole elegant mechanism could collapse.

She learned the plant like a map she might someday need to escape. Shift times. Guard routes. Inspection routines. Serial number ranges. The layout of the parts racks. The sound each line made when it ran right, and the slightly wrong hum when something was off.

And then, one winter night, her bicycle broke.

Late February 1944. The wind knifed across Kassel, and snow clung stubbornly in the cracks between cobblestones. Lotte pedaled home, shoulders hunched, fingers numb on the handlebars.

Halfway up a hill, the chain skipped.

A sharp metallic snap, her pedals spun free under her boots, and she coasted to an awkward stop beneath a darkened streetlamp. Cursing under her breath, she knelt and flipped the bike, the front wheel turning lazily in the air.

One link in the chain was bent. Not much. Just enough.

She wrestled the chain off the sprocket and worked it free. The damaged link had worn unevenly; the inner pin was pinched slightly out of round. Under just the wrong load, at just the wrong angle, it jammed. The whole chain seized.

One bad link, and the entire mechanism failed.

She held it up to the lamplight, turning it between her fingers. The cold metal stuck to her glove. Behind her, the distant rumble of the factory washed over the city.

“If one link can stop a bicycle,” she whispered to herself, “why not a tank?”

She stayed up all night.

On the table in her cramped apartment, next to an empty bread plate and the stub of a candle, she spread out what she knew. The Panzer IV gearbox in her mind. The primary drive chain that carried torque from engine to transmission. The point where the load was greatest.

She didn’t have blueprints. She had memory and touch.

The weak spot was obvious once she thought like an enemy instead of a mechanic: the coupling chain between the first and second drive gear. Put the flaw there, and the moment full power hit, the defective link would deform. The chain would lock. The gearbox would freeze.

Outwardly, everything would look perfect—weighed and measured, within spec. Only when the tank tried to move would the sabotage appear.

She needed a link that looked identical to the originals, behaved like them under normal test loads, and then failed in exactly the right way at exactly the wrong time.

So she started making them.

From scrap bins in the gearbox shop, she collected offcuts of chain and sprocket steel and smuggled them home in her pockets. At night, she clamped them in a vice and filed them into shape. Too brittle, and they’d crack during bench testing. Too soft, and they’d deform under low load and get caught by inspectors.

She hardened samples over a candle flame, quenched them in water, and listened to the file’s drag across their surface until she found a tone she recognized: not too high, not too low. Resilient, but with a fault hidden in its heart.

Night after night, she tested. At work, she watched the inspection routines. The men at the bench applied torque, but never enough to simulate the strain of a 45-ton tank trying to climb a hill in winter mud.

The system trusted itself.

Her plan was brutally simple: during one long night shift, she would open gearbox housings on the final inspection rack and swap one link in each drive chain for one she had made. Not every unit—just enough. Too many failures and the pattern might be obvious. Too few and the disruption would be absorbed.

She made thirty-six links. Thirty-six bullets.

On the evening of March 12th, 1944, she went to work.

The night shift clocked in just before eleven. The plant was a dim orange world, the high windows painted black, lamps hooded, welding arcs flashing like distant lightning.

Lotte signed in on the time sheet—“Bäuer, L. – Schicht C, Getriebe”—and walked calmly to her station. In her satchel the cloth pouch felt very heavy.

The guard at the inspection table unfolded a newspaper and parked himself on a stool, his flashlight on the floor by his boot.

The line began to move.

Gearboxes came down the conveyor in steel cradles, pausing briefly at her maintenance station. She waited until the inspector turned away to argue with a foreman, then slid the cover off her first target.

The drive chain gleamed under her lamp. She loosened a tension pin, popped out one original link, and slipped in her own. It fit like it had always belonged there.

Casing back on. Bolts tightened. Grease smear wiped.

Two minutes. Done.

She did it again. And again.

Every fifth gearbox. Thirty units by 0317.

Once, the sergeant got up, folded his paper, and did his little patrol. His boots clanged past just as Lotte held an open gearbox in front of her, defective link half installed.

She bent low, pretended to retighten a bolt. His flashlight beam slid like a searchlight across the metal. It lingered, just long enough for her heart to stop, then moved on.

“Don’t stay after the bell,” he muttered. “We’re behind as it is.”

She nodded without looking at him. When he turned the corner, she let out a breath she hadn’t known she was holding. Her hands shook. Her work didn’t.

At 5:12 a.m., she wiped her bench clean, ticked “inspected and cleared” on thirty gearbox cards, and walked out.

Her time card stamped at the clock: 05:12 – end of shift.

Ten minutes later, she was on her bicycle, pedaling past the railyard where finished tanks waited in rows, dark shapes in the dawn. The siren that would become infamous—internal mechanical alarm, not air raid—hadn’t sounded yet.

Behind her, the bell rang to start the day shift.

Ignitions were turned.

The sound came like breaking teeth.

Engines roared to life, diesel exhaust pouring toward the roof. For a few seconds, Hall 7 sounded like every other morning: the building shaking with simultaneous startups, the vibration running through the soles of workers’ boots.

Then, a sharp metallic crack. A grinding shriek. Another. Then dozens.

Torque gauges spiked into the red. A tank lurched a meter forward and died. Another kicked sideways on its test stand, jamming the unit next to it. Within two minutes, fifty engines had choked themselves to silence against fifty seized transmissions.

Sparks sprayed from a pump as an operator tried to force more oil into a frozen housing. “Alles aus! Alles aus!” the foreman screamed, waving his arms. “Shut everything down!”

The factory ground to a halt.

By seven, supervisors were in a shouting match. By eight, the plant manager was on the phone to Berlin. By noon, telegraphs were describing “catastrophic transmission failures in all units completed night 12–13 March. Cause unknown.”

The Gestapo arrived the next day.

They dragged forced laborers from the line. They beat a Polish mechanic until he couldn’t stand. They interrogated foremen and inspectors, hammering their fists on tables.

They found nothing.

Engineers dismantled gearboxes, measured every gear tooth. Everything looked perfect. Every dimension was within tolerance. Yet when reassembled and tested under load, the transmissions froze every time at the same torque.

It took days before one junior engineer, bleary-eyed over a magnifying glass, noticed tiny scratches on an inner face of a chain link. On another unit, microscopic heat distortion exactly where no heat should have been.

Under test, both links deformed at 650 newton-meters of torque.

Exactly when they had been designed to fail.

He wrote a report. His boss read it, went white, and tore it in half.

“There is no sabotage in Kassel,” he said. The fragments went into the furnace.

Officially, it remained “a manufacturing anomaly.” Unofficially, everyone in the plant understood: somebody had done this on purpose.

They just didn’t know who. “Bäuer, Lotte” was already gone. Her bicycle found leaning against a railing by the Fulda. Her file stamped “Krank – beurlaubt.” Sick leave.

No trace. No confession. No explosion to point at on a map.

Just fifty tanks that never moved.

History tends to record what blows up, not what quietly fails to start.

Those fifty tanks were destined for the 56th Heavy Panzer Battalion. They were supposed to reinforce Army Group South just as the Red Army was preparing its spring offensive.

Because of the “mechanical losses at depot,” those tanks arrived six weeks late.

Because of that delay, one German regiment fought without armor support on the Dniester, then broke under pressure. Supply depots had to be abandoned. Soviet infantry crossed where they shouldn’t have been able to.

British intelligence later estimated that the failure at Kassel robbed Germany of roughly a division’s worth of combat power at a critical moment.

Did it win the war? No.

Did it save lives? Yes.

Thousands, possibly tens of thousands.

Not with a bomb. Not with a gun.

With thirty chain links and a bicycle mechanic’s hands.

When the Allies reached Kassel in 1945, the Henschel plant was a smashed shell. Archives burned. Machines twisted. No one was looking for one woman on a bicycle.

Decades later, when historians finally dug through what was left, they found a few traces.

A maintenance log with “Bäuer L. – Schicht C” penciled in. A British engineer’s field note: “Multiple gear units show identical torque seizure. Cause appears deliberate.”

In the 1970s, a German researcher at the Kassel museum opened an unmarked envelope in a box of old reports. Inside was a single chain link mounted on a steel tag: “Recovered, Kassel, 1944.”

Its metal composition was slightly off from standard. Its machining bore the telltale signs of hand filing. In a lab test, it deformed at exactly the torque the wartime notes mentioned.

Whoever made it knew exactly what she was doing.

Today, that link sits under glass in a small museum display. Visitors usually walk past it on their way to the big things—the tank hulls, the engines, the uniforms.

The label is short.

One defective link. 50 tanks stopped. Thousands spared.

No name.

No photo.

Just the weight of that simple equation.

Wars are usually told through the loudest moments—battles, explosions, declarations. But they’re also shaped by decisions made in the quiet. By people who choose, at great personal risk, not to keep the machine running.

Lotte Bäuer didn’t blow up a factory. She didn’t assassinate a general. She didn’t hijack a train.

She looked at a chain link, listened to how metal failed, and decided to turn her skill the other way.

She didn’t end the war.

But she jammed the gears.

And in a world built on steel and obedience, that’s sometimes the most powerful act of all.

News

(CH1) Admirals Called Her Chalk Trick “STUPID” – Then It Saved 48,000 Lives

At 6:43 on a raw March morning in 1943, a nineteen-year-old woman stood in a cold Liverpool basement and looked…

(CH1) How One Girl’s “SILLY” Chalk Trick Made German U-Boats Sink 3 Times Faster

At 6:43 on a cold Liverpool morning in March 1943, a nineteen-year-old woman stood in the middle of a painted…

(CH1) How One 14-Year-Old Girl’s “Crazy” Bicycle Trick Killed Nazi Officers

In the history of warfare, death usually wears a uniform. It arrives with the thunder of artillery, the scream of…

(CH1) How One US Woman’s “Shopping Trips” Saved 7,000 Allied Pilots from Nazi Prisons

March 2nd, 1943. Marseille. The coded telegram was short, cold, and devastating. “Pat has fallen.” Four hundred kilometers away, in…

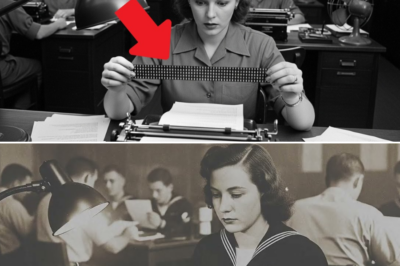

(CH1) How One American Woman’s Torn Typewriter Ribbon Saved 3,000 Lives and Sank 4 Japanese Carriers in 5 Hours

At 4:17 a.m. on May 25th, 1942, the ocean was still dark outside Honolulu, but inside the Fleet Radio Unit…

(CH1) How One Female Sniper’s “CRAZY” Trick Took Down 309 Germans in Just 11 Months

5:47 a.m. – August 8th, 1941. Belaya Tserkov, Ukraine. Twenty-four-year-old history student Lyudmila Pavlichenko crouched behind a pile of shattered…

End of content

No more pages to load