The winter of 1945 did not simply arrive in Germany; it descended like a curse.

Snow lay in dirty heaps between piles of bricks where houses had once stood. Chimneys jutted out of rubble like broken fingers. In what had been the small, prosperous town of Schwäbisch Gmünd, twelve-year-old Lisel Hoffmann pressed her back against the cold stone wall of a bombed-out bakery and held half a loaf of bread tight against her chest. It was hard as timber, the crust flaking with age. It had probably been baked weeks ago.

To Lisel, it was precious all the same. That bread was supposed to keep her and her little brother alive for three, maybe four days if they were careful. Hunger made careful difficult.

Her father had fallen at Stalingrad three years earlier, a place that had turned from a name on a map into a graveyard for an entire generation. Her mother had died of typhus the previous autumn. Since then, Lisel and her eight-year-old brother Friedrich had learned how to move like ghosts through the ruins, trading old clothes for potatoes, stealing a coal here or a turnip there, doing whatever was necessary to see the next sunrise.

From the shattered bakery window, Lisel could see the street. That morning it was filled by a slow-moving column of men. Prisoners. They shuffled past under the watch of Wehrmacht guards who looked scarcely better fed than those they herded. There was nothing triumphant about them now. These were not the soldiers the posters had shown, all sharp uniforms and sharp smiles. These were men with hollow cheeks and vacant eyes, moving because someone behind them still carried a rifle.

Among the prisoners, one uniform snagged Lisel’s eye. It was not German field grey, but a ragged, faded blue. The remnants of an RCAF tunic clung to a young man whose legs seemed to be folding beneath him with every step. She recognized the shape of the wings on his chest from leaflets and propaganda charts. An Allied pilot, she thought. A bomber crewman.

His name was Thomas Edward McKenzie, though that meant nothing to Lisel then. He was a farmer’s son from Saskatchewan who had enlisted in 1941 convinced, like so many, that the war would be an adventure before it was a duty. Those illusions had burned away somewhere over the Ruhr when German flak turned his Lancaster into a falling fireball. Six months in Stalag Luft III had reduced him further. The march—one of many that would be remembered as the “death marches” of that final winter—had finished the job.

On this bitter February day, Thomas’s legs finally surrendered. He stumbled, lurched sideways out of the column, and crumpled into the snow. His breath came in short, shocked gasps, forming small clouds in the air. The guard nearest him shouted something hoarse and angry, but did not stop. Perhaps he was too exhausted himself. Perhaps he knew the war would be over soon and could not bring himself to fire another shot. Whatever the reason, the column moved on without Thomas, its sound fading up the street.

When the last man had vanished around the corner of a ruined church, silence reclaimed the square.

Lisel looked down at her bread. Friedrich was asleep on a pallet in the corner behind her, wrapped in their mother’s old coat, his thin shoulders rising and falling with each laboured breath. The bread was their lifeline. Without it, there would be nothing between them and the emptiness that had already taken so many.

To share it was to bet against survival.

She looked back at the young man in the snow. He lay very still now. Not dead—she could see his shallow breathing—but not trying to stand, either. Lisel had seen a similar look in her mother’s eyes just before the end: that quiet surrender that comes when the body has finally convinced the mind that there is no point in struggling.

Her fingers trembled.

Then she broke the loaf in half.

The bread cracked with a sound that seemed too loud in the stillness. She put one piece back under her coat for Friedrich and stepped out into the street with the other.

The snow was crusted over with a thin layer of ice. It crunched under her bare feet in worn-through shoes. Every step took courage she was too hungry to feel. In 1945, compassion was dangerous. Everyone knew of people shot for less than this—sharing potatoes with forced labourers, giving water to prisoners, expressing doubt that the promised “final victory” would ever come.

She reached the pilot and crouched beside him. He flinched at the sound of her approach, his eyes opening in panic. For a moment they simply stared at one another: a half-frozen Canadian in a shredded uniform and a German child in rags, each shocked by the existence of the other.

She held out the bread.

“Bitt,” she whispered. It was one of the few English words she knew—or thought she knew. Please.

For a moment he didn’t move. The absurdity of it froze them both: a starving German girl offering food to an enemy prisoner in a ruined town in a defeated country.

Then his hand closed around the crust.

He tried to give some of it back almost immediately, breaking off a piece and holding it out to her, but Lisel shook her head and took a step backwards.

“Für dich,” she said, backing away, eyes flicking nervously to the end of the street where the column had vanished. “Für dich.”

Thomas’s throat closed. Tears burned his eyes, hotter than the wind that scoured his face. He hadn’t cried when his plane fell from the sky, nor when friends died in camp huts beside him, nor during the nights on the march when the cold seemed to seep into his bones. But this—this inexplicable grace from a child who owed him nothing—shattered something inside him.

“Thank you,” he managed, voice ragged. He knew she wouldn’t understand the words, but he hoped she would hear the gratitude in them.

By the time he looked up again, she was gone, vanished back into the ruins as silently as she had come.

The bread was old and hard, but it tasted better than any meal he had known. It put enough strength back into his body to let him stand when another group of prisoners and guards came through an hour later. He rejoined a different column. Three weeks later, near Stuttgart, American forces overtook that column. Thomas was liberated, sent to England, and eventually shipped home.

He returned to Canada. He married Dorothy, the daughter of a neighbouring farmer. They had three children. He tilled the same soil his father had, watched wheat rise and fall with the seasons, learned to live again in a land of wide skies and peace.

But he never forgot the girl in the snow, or the taste of that bread, or the fact that, at a moment when the world had seemed determined to prove that humans were nothing but beasts in uniforms, a child had chosen compassion over instinct.

Lisel survived the war too. She kept Friedrich alive through the chaotic weeks of collapse that followed, scavenging from American relief stations, sneaking into fields, accepting the occasional handout from soldiers who had more food than they needed and the grace to share it. In May, when the Third Reich finally fell and the guns went quiet, she was still there, as skinny as a ghost but unbroken.

She grew up in the ruins, then through the rebuilding. In the 1950s, she married Hans, a carpenter with steady hands and a quiet nature. They moved to Esslingen am Neckar, not far from where she had watched that column of prisoners pass. Hans’s business prospered in the economic miracle that remade West Germany. They had two daughters: Anna, who inherited Lisel’s blue eyes, and Christina, who inherited Hans’s thoughtful calm.

Lisel scarcely spoke about the war. When television documentaries showed footage of rubble and camps and men in brown uniforms shouting into microphones, she left the room. When her daughters asked what it had been like, she gave them the bare facts: her father had died in Russia, her mother of illness, there had been hunger and fear.

She never mentioned the Canadian.

The memory stayed tucked away like the folded winter scarf at the back of the closet—kept, but not used. In a childhood dominated by hunger and terror, that one small moment of giving had been a tiny flame. She wasn’t sure she wanted to expose it to any more air in case it went out.

Thomas, thousands of kilometres away on the Canadian prairie, carried the same memory.

He rarely talked about the war. His children knew he had been a pilot and spent time in a camp. They knew he sometimes woke up at night sweating, that he didn’t like fireworks or low-flying planes. They did not know that in his desk drawer, under a stack of farm receipts, he kept a small, rock-hard piece of bread wrapped carefully in cloth.

In 1970, the weight of unspoken memory became too much.

It may have been age—he was pushing fifty—or the way news from Vietnam brought back too many images he’d tried to bury. One autumn evening, sitting at the kitchen table with a cup of coffee cooling between his hands while Dorothy read the newspaper and the television muttered in the next room, he simply said it.

“I need to find her.”

Dorothy looked up. He didn’t need to explain who.

“Tom,” she said gently, “she could be anywhere. She might be…” She stopped short of the word.

“I know,” he replied. “But I have to try. I need to tell her it mattered.”

He wrote to the Canadian embassy in Bonn, to veterans’ associations, to the Red Cross. He described what he remembered: February 1945, prisoner march, near Schwäbisch Gmünd, a thin blonde girl about twelve, giving him bread. Most responses were polite but unhelpful. Some suggested that he let the past rest.

He didn’t.

Eventually, with the help of embassy staff, he placed a small notice in a handful of German regional newspapers. It asked for information about a German girl who had given bread to a Canadian prisoner in Schwäbisch Gmünd in early 1945. It included a post office box in Bonn where replies could be sent.

In Esslingen, one November morning, Lisel stopped at the vegetable stall in the market. A woman she knew casually from church was waving a newspaper around, excited.

“Can you imagine?” the woman said to a friend. “Some Canadian veteran is looking for a German girl who helped him during the war. He’s offering a reward. It’s like one of those films.”

“May I see?” Lisel asked.

She took the paper and scanned the article. The details were impossible to ignore: Schwäbisch Gmünd, February 1945, a little girl, a piece of bread. Her hands began to shake. The market blurred.

“Are you all right?” the woman asked. “You look pale.”

“I’m fine,” Lisel said. “Just a headache.”

She walked home with her vegetables and the newspaper and sat at the kitchen table for a long time. Hans was in the workshop out back. The girls were at school. The house was quiet.

The secret she had carried for twenty-five years lay on the table in black ink.

She didn’t write that day. Or the next. But she kept the clipping in the drawer where she stored family papers.

The decision came, unexpectedly, at another kitchen table moment. It was December, and outside the first snow of the season dusted the roofs. Christina, the younger daughter, was bent over a homework assignment.

“Teacher says we should ask what it was like for you in the war,” she said. “So we don’t forget. So it doesn’t happen again. What was it like when you were my age?”

“Hard,” Lisel said. “We were hungry. The city was bombed.”

“Did you ever see any enemy soldiers?” Christina asked.

Hans, reading in his chair, lowered his magazine slightly.

“Yes,” Lisel said. “Once, a Canadian pilot on a march. He fell in the snow outside a bakery. I gave him bread.”

“Did he live?” Christina asked, wide-eyed.

“I don’t know,” Lisel said. Then, after a pause: “He’s looking for me.”

She showed them the clipping. Hans listened, surprised but not as shocked as she had feared. Their daughters leaned in, fascinated.

“Will you answer?” Anna asked.

“I…don’t know,” Lisel admitted. “It means opening everything up again.”

Hans reached across the table and put his hand over hers. “Maybe it also means closing something, properly, instead of just shutting it away,” he said.

That night, after everyone had gone to bed, Lisel sat alone with pen and paper. She began formally, in German, “Sehr geehrter Herr McKenzie…” Dear Mr McKenzie. She tore up the first attempt. And the second. The third letter made it to the second paragraph before her hand refused to go on.

The version that finally made it into an envelope was simple.

She told him her name and that she believed she was the girl he remembered. She described the ruined town, the march, his fall in the snow, her hunger, Friedrich asleep in the bakery. She admitted that she had often wondered if he had survived.

She wrote that she hoped he had.

When the letter reached Saskatchewan some weeks later, Thomas read it at the same kitchen table where he had announced his search. The paper shook in his hands. Dorothy watched in silence until he looked up.

“She’s alive,” he said. “Her name is Lisel. She married. Two daughters. And she remembers.”

He wrote back. Letters crossed the Atlantic, a thin paper bridge carrying two lives.

He told her about the farm, about Dorothy, about the children. He told her about waking up at night and seeing snow and a girl and bread. About the piece of that loaf he had kept in his drawer, hardened under glass like a relic.

She told him about rebuilding, about her marriage, about guilt. About the day she had given him half their food and the weeks afterwards when she wondered if she had doomed her brother.

Over time, the correspondence grew more personal, less formal. They spoke of the present as much as the past. Letters piled up—over forty in all according to a later archivist’s careful count.

In 1973, they met.

Thomas and Dorothy arranged for Lisel and Hans to fly to Canada. At the small airport in Moose Jaw, Thomas recognised her at once. The lines of age on her face didn’t erase the structure he had stored in memory. She saw him and saw, behind the farmer in his Sunday suit, the young man shivering in German snow.

They hugged awkwardly at first, then with the easy warmth of recognition. Their spouses smiled and stepped back, giving space to people who had been waiting decades for this embrace.

They spent a week on the farm. Lisel walked through wheat that reached her waist, marvelled at the sheer space of the prairie. Dorothy and she cooked together, laughing as they invented a shared language of gestures and a few words. Their children—a Canadian brood and two German sisters—got used to each other’s accents and discovered shared tastes in music and books.

On a clear afternoon, Thomas took Lisel to a small cemetery where his father lay. Sitting on a stone bench among the graves, he told her, in halting phrases, how that moment in the snow had outlived all the others.

“I had given up,” he said. “You made me stand up again.”

“I was afraid,” she replied. “But I thought of my father. I hoped someone had been kind to him once. So I was kind to you. That’s all.”

It wasn’t all, of course. It was the difference between life and death. Between one farm being tended and one lying fallow. Between one Canadian family and the absence that would have shaped it.

Before she left, he gave her the preserved piece of bread. She refused to take it.

“Keep it,” she said. “Tell the story.”

They did. Together they spoke at a reconciliation event in Ottawa in 1985, two former enemies on a stage talking about bread and snow and how small choices matter. Their story spread, cited in articles and documentaries as an example of how wars are not only about destruction but also about the fragile threads of humanity that survive.

In 1995, fifty years after that winter, they stood in Schwäbisch Gmünd again. The town was rebuilt. The bombed bakery was an apartment building. The street had a new name. They couldn’t find the exact spot where Lisel had stood with her back to a wall holding a loaf like a treasure.

“It doesn’t matter,” Thomas said when she expressed regret. “What matters is that it happened.”

A small plaque in the town square carried their names and a simple inscription about an act of kindness between enemies. People passed it on their way to shops and offices, most barely noticing. But sometimes a child would stop and read it, ask a question, and the story would be told again.

Thomas died in 2003, at eighty-one. Lisel four years later. Their children and grandchildren still write to each other at Christmas.

Somewhere in two family homes, in Canada and Germany, there are photographs of them together and a small wooden box with a piece of bread under glass.

It is useless now—too old to eat, too brittle to touch. But its meaning has not aged.

In a winter when the world seemed determined to prove that humans were cruel by design, a starving girl broke her bread in half and gave it away. A dying man accepted it and carried the memory home.

Everything that followed—the letters, the meeting, the plaque in a rebuilt town—grew from that.

History will always record the dates and troop movements and treaties of 1945. But somewhere between those lines lives another kind of record, made not with ink but with hands and choices.

On a ruined street, in a defeated country, someone chose to be human when it was least expected.

And that, in the end, is the kind of victory that lasts.

News

(CH1) Admirals Called Her Chalk Trick “STUPID” – Then It Saved 48,000 Lives

At 6:43 on a raw March morning in 1943, a nineteen-year-old woman stood in a cold Liverpool basement and looked…

(CH1) How One Girl’s “SILLY” Chalk Trick Made German U-Boats Sink 3 Times Faster

At 6:43 on a cold Liverpool morning in March 1943, a nineteen-year-old woman stood in the middle of a painted…

(CH1) How One 14-Year-Old Girl’s “Crazy” Bicycle Trick Killed Nazi Officers

In the history of warfare, death usually wears a uniform. It arrives with the thunder of artillery, the scream of…

(CH1) How One US Woman’s “Shopping Trips” Saved 7,000 Allied Pilots from Nazi Prisons

March 2nd, 1943. Marseille. The coded telegram was short, cold, and devastating. “Pat has fallen.” Four hundred kilometers away, in…

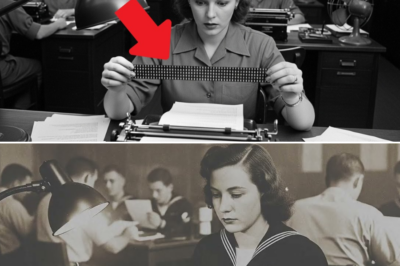

(CH1) How One American Woman’s Torn Typewriter Ribbon Saved 3,000 Lives and Sank 4 Japanese Carriers in 5 Hours

At 4:17 a.m. on May 25th, 1942, the ocean was still dark outside Honolulu, but inside the Fleet Radio Unit…

(CH1) How One Female Sniper’s “CRAZY” Trick Took Down 309 Germans in Just 11 Months

5:47 a.m. – August 8th, 1941. Belaya Tserkov, Ukraine. Twenty-four-year-old history student Lyudmila Pavlichenko crouched behind a pile of shattered…

End of content

No more pages to load