The desert around Camp Florence looked like the end of the world.

In April 1945, the sun beat down so hard the horizon seemed to shimmer. Dust clung to everything—boots, fences, the rough wooden barracks—and the air smelled of hot sand, diesel, and something faintly metallic. When the transport truck finally lurched to a stop and the tailgate banged open, the women inside had to blink against the brightness.

They climbed down slowly, wrists still raw where ropes had rubbed during the long journey. Twelve of them, all in faded field-gray, hair tied back, faces hollow from weeks of hunger and fear. Nurses. Clerks. Radio operators. They had been told since childhood that this was the worst possible destination.

America.

They’d heard the phrases again and again: Yankee savages. Jewish puppets. Weak and decadent, cruel in victory. At Munich station three months earlier, as Greta Hoffmann boarded the train that carried Wehrmacht auxiliaries west into chaos, her grandmother had grabbed her face with bony fingers and hissed a final instruction.

“They will starve you. Beat you. Parade you like animals. Don’t let them break you. Better to die with honor.”

Greta had believed her. She believed it now as her boots hit Arizona dust and the heat wrapped around her like a punishment.

The first person to greet them was not a barking sergeant with a whip, but a woman with lieutenant’s bars on her shoulders and a clipboard in her hands.

She had dark hair pinned tight at the back of her head, an angular jaw, and an expression that gave nothing away. When she spoke, the German was crisp and precise.

“I’m Lieutenant Sarah Tanaka. Welcome to Camp Florence. You’ll be processed, assigned bunks, and given work details. Follow me.”

That word—welcome—landed oddly in the women’s ears. No dogs strained at chains. No insults. No raised hands. Just a woman in a pressed uniform turning sharply and leading them toward the gate.

Processing took an hour: names checked against lists, tags issued, photographs taken under the hard desert light. The barracks they were led to afterward smelled of pine boards and dust. Each bunk held a thin mattress, two folded blankets, and, impossibly, a bar of Ivory soap resting on the pillow.

Greta picked hers up, turning it over as if it might crumble into ash. White, clean, faintly scented. It had been months since she’d had more than a splash of cold water and a sliver of gray ersatz soap.

“Where are the whips?” Anna, the youngest, whispered, eyes huge. “Where are the dogs?”

No one answered. They were all thinking the same thing: the real cruelty must come later.

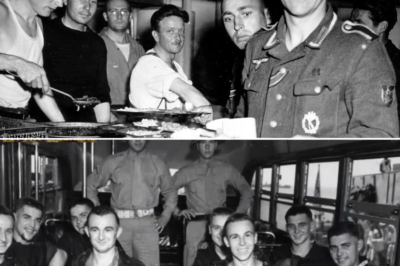

It did not arrive at the mess hall.

At six o’clock, the bell rang. The women filed in, shoulders tight, braced for watery soup and moldy bread. The smell that hit them stopped them in their tracks.

Roasting meat. Fresh yeast. Coffee.

Real coffee.

Behind the serving line stood an American sergeant wearing a stained apron and an easy grin. He ladled food onto tin trays without ceremony. When Greta held hers out, his spoon moved in a practiced arc. A thick slice of beef roast, pink at the center. A mound of mashed potatoes with a square of butter melting into a golden pool. Green beans glistening with fat. A roll that yielded steam when she pressed it lightly. Canned peaches in sweet syrup.

“This is American prison food,” Greta whispered in disbelief.

The words had barely left her mouth when someone slapped the fork from her hand. Metal clattered across the floor.

“Don’t touch it,” hissed Lisel Weber, thirty-eight, with eyes like chipped glass and the hard bearing of a former SS auxiliary. “It’s poisoned. They want us docile. Then…” She drew a finger across her throat. “Then comes the real punishment.”

It made sense. It fit everything Greta had been told. You didn’t feed your enemies this well unless you wanted something from them—or unless you were fattening them up for slaughter.

Then Lieutenant Tanaka sat down across from them.

Her tray matched theirs exactly, down to the number of green beans. She cut a piece of beef with calm precision, ate it, chewed, swallowed, and wiped her knife on a slice of bread.

“Article Twenty-Six of the Geneva Convention,” she said, her tone flat. “Prisoners of war receive the same rations as the captor nation’s troops. You can read the Red Cross inspection reports in the barracks if you like. They’re posted on the wall.”

Greta stared at her. At the food. At the other Americans laughing and eating the same meal a few tables away. If this was a trick, it was an elaborate one.

That night, after lights out, she lay on her bunk with half the roast wrapped in a napkin and hidden in her sleeve. Her stomach twisted between hunger and shame. In the darkness, she lifted the meat to her mouth and bit.

It tasted like salt and fat and something she would later recognize as the first crack in the world she’d known.

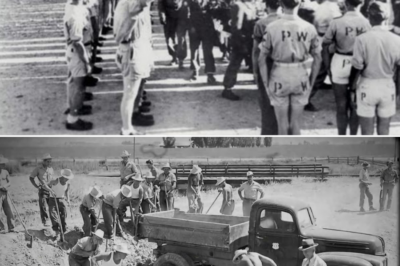

Camp Florence ran on routine: reveille at dawn, roll call, work assignments, mail call, lights out. The work was dull but humane—laundry detail, kitchen help, sewing uniforms. Pay came in the form of paper camp scrip, a few cents a day that could be used in the canteen.

The first time Greta held those flimsy notes in her hand, she felt faint. Eighty cents for a long day hauling wet uniforms from industrial washers to clotheslines that shimmered in the heat. More money than she’d had at one time since the war began.

At the camp store, she stood in front of the shelves as if they were altars. Bars of soap. Combs. Writing paper. Toothpaste in shiny tubes printed Colgate. A bored American corporal took her scrip, handed over the items, and barely looked up.

Anna bought cigarettes. She didn’t smoke, but held the pack tightly, another small insurance against the fear that all this would suddenly vanish.

Greta watched Lieutenant Tanaka move through the compound. Sarah’s steps were measured. Her uniform was always immaculate. When guards shorted a prisoner a dessert portion as a joke, Sarah reassigned them to night watch for a month. When she caught one of the women hoarding bread in the barrack footlocker—a hard habit to break in people who’d known hunger—she confiscated it without theatrics and recorded the incident, writing in a neat script across a report form.

It was the restraint that baffled Greta most. Sarah’s parents, she overheard, had lost their business on the West Coast when Japanese Americans were rounded up and sent to internment camps. Her brother had died in Italy fighting in the very uniform she now wore. Sarah had every reason to hate, yet she monitored calorie counts and medical charts, not as acts of personal generosity, but as obligations to a law she was unwilling to break.

One evening, when the barracks were nearly empty—most of the others had gone to the recreation hall to watch a movie—Sarah found Greta sitting on her bunk staring at a blank sheet of paper. A pencil rested in her hand.

“Writer’s block?” Sarah asked, switching to German.

“I don’t know what to say,” Greta answered. “If my family is even… there to read it.”

“The truth is usually a good place to start,” Sarah said.

“The truth is I’m being treated better here than I ever was at home,” Greta snapped, surprising herself with the bitterness in her own voice. “I eat steak while they starve. How do I write that?”

Sarah’s gaze flickered—just once, just enough to reveal the human behind the officer.

She reached into her bag and pulled out a small clothbound book. A German-English dictionary, its edges worn soft.

“Then start simple,” she said, placing it on the bed. “Tell them you’re alive. Let everything else wait.”

After she left, Greta opened the book. The pages smelled of dust and old ink. She traced words with her finger. Alive. Safe. Enough.

She wasn’t sure yet that she believed them.

The newsreels arrived in late May.

By then, the war in Europe was officially over. The camp grapevine had carried the news before the announcement. Hitler was dead. Germany had surrendered unconditionally. The Reich that was supposed to last a thousand years had burnt itself out in twelve.

On a hot evening, Sarah assembled all the women in the camp theater, a low building with a white sheet tacked up as a screen. The air inside was close, smelling of sweat and sawdust.

“V-E Day was two weeks ago,” she said in German, her voice flat and steady. “You know Germany has surrendered. What you have not seen are the camps. Tonight you will. No one leaves early.”

The lights went down. The projector clattered to life.

Greta lasted fifteen minutes.

Bergen-Belsen appeared first: heaped corpses like bundles of sticks, survivors staggering with eyes sunk deep in skulls, British soldiers wearing masks to block the smell as they pushed bodies into trenches with bulldozers. Dachau. Buchenwald. Auschwitz.

Greta stumbled out into the desert air and fell to her knees behind the theater, retching into the dust until there was nothing left.

She didn’t hear Sarah approach.

“Did you know?” Sarah asked quietly.

“No,” Greta whispered. “I was signals. A radio operator. I never saw…”

Words tangled in her throat. She’d heard jokes about “resettlement.” She’d heard rumors of ghettos and special trains. But she had never connected the dots, never let herself imagine what the euphemisms might mean.

“But I should have asked,” she choked. “We all should have. We sent messages. We never asked what they were for.”

Sarah sank into a squat beside her, boots crunching in the gravel.

“My parents lost their grocery store in San Francisco,” she said. “Thirty years of work gone in a week. My brother enlisted to prove we belonged here. He died with a U.S. flag on his coffin. And yet the law says that I feed you good food and make sure nobody lays a hand on you. That I call you ‘Miss’ and ‘Frau’ instead of ‘Kraut.’”

She looked back at the theater, where flickers of horror still danced against the inside walls.

“Restraint isn’t softness, Greta,” she said. “It’s the line between us and that.”

For once, Greta didn’t argue. She had no defense left.

The letter from Germany arrived in early June.

Red Cross envelope. Thin, too thin. Greta held it in both hands as if the paper might disintegrate. The script inside was unfamiliar, crabbed, and official. A neighbor, forced to play messenger of other people’s grief.

Her mother and younger brother killed in the Dresden firestorm that February. Her father missing, last seen somewhere along the Elbe, believed dead. Her grandmother, the one who had told her to die with honor, found hanging in the garden shed two days after the surrender.

The letter was dated months before, when all of it had been fresh.

Greta folded it carefully and placed it under the dictionary in her footlocker. Then she stopped eating.

Steak, potatoes, coffee—the abundance that had once felt like an affront to her pride now looked obscene. She sat in front of her tray in the mess hall until the food congealed and the room emptied around her.

“You’ve got to eat something, ma’am,” Jimmy told her, the easy humor gone from his voice.

It took Lieutenant Tanaka’s formal authority to get her moved from her bunk to a chair in the infirmary, the frame of her body already thinning.

“Don’t do this,” Sarah said. “You starving yourself won’t bring them back.”

In the barracks, Lisel interpreted the news in her own way.

“I told you,” she said, voice low and fierce, cornering Greta after lights out. “While Germany burned, you ate steak with the enemy. You sang songs with them. You chose them. And now you think you can just go home?”

Greta hit her then. Hard. Fury, guilt, grief—all of it exploded, sending both of them crashing into a bunk with fists flying. It took two guards to drag them apart and a report thick with ugly accusations to land Greta in an isolation cell.

Three days in a concrete room with only a cot and a metal bucket gave her time to stare straight at the questions she’d been dodging.

Did surviving in comfort while her family died make her a traitor? Did accepting mercy mean betraying the dead? If the enemy showed her more humanity than her own leaders had shown their victims, where did that leave her?

On the third day, Sarah came to the cell.

She didn’t unlock the door. She simply sat with her back against it and spoke through the bars.

“You didn’t choose to get captured,” she said. “You didn’t choose to be fed, or to see those films, or to have your world ripped open. You only choose what you do now.”

Greta closed her eyes.

“I should have died with them,” she said. “That would have been honest.”

“Honest to who?” Sarah’s tone sharpened for the first time. “To a grandmother who’d rather hang herself in a shed than face that she’d believed in a lie? To men who filled trains and built chimneys and then called it glory? No. You don’t owe them your death. You owe the living your work.”

Work on what? That question hung in the air, unanswered.

The answer arrived, in a way, in an envelope.

The International Red Cross, overwhelmed by pleas from displaced families in Europe, sent a representative to Camp Florence looking for German speakers who could help trace missing persons, translate letters, and fill out forms.

Sarah put the request in front of Greta as soon as she came out of isolation.

“Mother in Tucson can’t find her daughter,” she said. “Last seen fleeing Munich. Needs someone who can read both languages and knows how our paperwork works. I told them you might help.”

Greta stared at the letter. The German script was desperate, specifics spilling out—dark hair, scar on left hand from a kitchen accident, last known address. The kind of details that only someone who had waited and worried and prayed would bother to write.

She translated the letter sitting on the barracks floor with the dictionary open at her side. She wrote replies to agencies in Switzerland, Germany, and the U.S. Army’s Civil Affairs division. For the first time since she’d arrived in Florence, her hand moved purposefully across the page.

Two weeks later, the Red Cross sent back news. The girl had been found alive in a displaced persons camp near Stuttgart. Mother and daughter would be reunited.

It was one life, one small victory against an ocean of loss. It shouldn’t have mattered as much as it did. But to a young woman whose family had all vanished, helping even one stranger find theirs felt like something solid to stand on.

When a Red Cross official visited again, recruiting staff for postwar relief, Greta raised her hand.

“You’re always choosing them,” Lisel said bitterly that night. “Choosing the enemy.”

“No,” Greta replied. “I’m choosing the people who need help—ours, theirs, everyone’s.”

By the time repatriation orders came that summer, Greta Hoffmann was no longer simply a prisoner. She was a trained translator with a battered dictionary, a scarred heart, and a stack of letters in her footlocker that proved she could be something other than a passive witness.

On the last day at Camp Florence, she turned in her blankets and mess tin, shook Jimmy’s hand in the kitchen, and held on a moment longer than necessary.

“Don’t forget to eat over there,” he said, trying to hide emotion behind a grin.

Sarah met her at the truck.

“We’re sending you to a Red Cross office in Stuttgart,” she said. “They’ll need people who can explain both sides to each other.”

Greta nodded. Words stuck in her throat. At the last moment she blurted, “Thank you.”

“For what?” Sarah asked.

“For treating me like the law said I was when you had every reason not to,” Greta said. “For making it harder to hate.”

Sarah’s mouth tightened, but her eyes softened.

“Good luck,” she said.

It was not forgiveness. It was not closure. But it was a beginning.

The trucks pulled out, dust rising in their wake. Camp Florence shrank in the rearview to a cluster of low buildings and fencing, then vanished altogether. Ahead lay ships, the Atlantic, and the ruins of a homeland she barely recognized in Red Cross photographs.

Behind her lay a place where she had eaten the enemy’s food, learned the enemy’s language, and discovered that the enemy’s mercy could demand more of her than their hatred ever had.

Years later, when she sat at a desk in Stuttgart helping yet another woman fill out missing-persons forms, a chipped bar of Ivory soap used as a paperweight, she would still remember the heat of the Arizona sun, the taste of that first American meal, and the moment a Japanese-American lieutenant invoked the Geneva Convention like a prayer.

She had gone to America expecting to die with honor.

She left with something far more complicated—and far more powerful: the conviction that law, restraint, and human decency, even toward one’s enemies, were the only reliable weapons left in a world that had nearly burned itself to death.

News

(Ch1) “It Felt Impossible” — German Women POWs Shocked by Women’s Freedom in the America

The wind coming off New York Harbor that afternoon was sharp enough to sting the eyes. Gray waves slapped against…

(CH1) The German POWs Mocked America at First—Then They Saw Its Factories

When the train slid to a stop in Norfolk in January 1944, the men inside braced themselves for the worst….

(CH1) When German POWs Reached America It Was The Most Unusual Sight For Them

By the time the hatch slammed shut on the Liberty ship and the Atlantic swells began to lift the hull,…

(CH1) “It Burns When You Touch It” – German Woman POW’s Hidden Injury Shocked the American Soldier

By the time the trucks pulled up to the gate at Camp Swift on May 12th, 1945, Texas heat had…

(CH1) The German POWs Laughed at American Food—Then They Ate in US Camps

They had laughed at America long before they ever saw it. Around smoky campfires in Russia and under low tarpaulins…

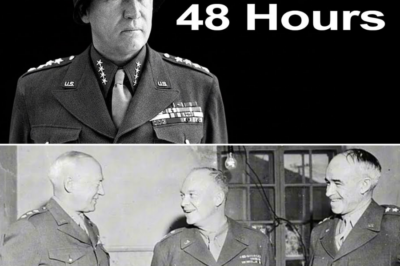

(CH1) Why Patton Was the Only General Ready for the Battle of the Bulge

On the night of December 19th, 1944, in a converted French army barracks at Verdun, the air in the conference…

End of content

No more pages to load