The wind coming off New York Harbor that afternoon was sharp enough to sting the eyes. Gray waves slapped against the hull as the ship eased toward the pier, its paint scarred by salt and time. On deck, thirty-odd women in drab field-gray uniforms stood shoulder to shoulder, waiting for orders that never seemed to come. Some hugged their arms tight across their chests. Others gripped the rail so hard their fingers blanched. All of them tried not to think about what might be waiting beyond the gangplank.

For weeks they had crossed the Atlantic in dim holds, hammocks swaying above greasy planks. They had lain awake listening to the heave of the sea and the low murmur of English voices. No one knew exactly where they were going, only that it was Amerika, and that word carried its own weight of fear and rumor.

They were nurses, typists, communications clerks, and war volunteers of the German Wehrmacht. None of them had fired a weapon in anger, but they had worn uniforms and served the regime that had dragged their country into total war. They had been told from childhood that Americans were crude, dangerous, and decadent. Propaganda in newsreels and newspapers painted them as a chaotic people ruled by greed and crime, led by Jewish conspirators and corrupt politicians. At best, the women were told, capture meant humiliation and forced labor. At worst, it meant worse things they did not name out loud.

So when the ship’s hatch finally clanged open and the first order barked up from the pier, many of them flinched. They gathered their few belongings—rolled blankets, a battered satchel, perhaps a photograph—and shuffled toward the gangway.

Then they saw who was waiting for them.

The pier was a living machine: cranes groaning over stacks of crates, trucks reversing in clouds of diesel fumes, gulls wheeling and crying overhead. American soldiers stood in ranks, rifles slung, helmets dull under the harbor light. But woven among the olive drab and steel were figures the German women had never imagined at the center of such a scene.

Women.

They moved with purpose between the clusters of guards and dockworkers, some in crisp khaki uniforms with insignia on their shoulders, others in trousers and rolled-up sleeves, clipboards tucked under one arm. One wore red lipstick above a sharp jaw and walked with the easy, straight-backed stride of someone used to being obeyed. Another pivoted on her heel, raised a whistle to her lips, and with one short blast sent a group of soldiers hurrying to help secure the mooring lines.

The prisoners stopped dead on the ramp.

“Are those secretaries?” someone whispered behind Lisa, one of the younger women.

“No,” another answered, staring. “They are in charge.”

On the pier a woman’s voice cut through the noise, clear and unhesitating. She stood by a folding table, calling out names from a manifest. American soldiers brought the women forward in small groups as she checked each tag, ticked off each entry, and directed them toward waiting trucks. The men did not contradict her. They did not smirk or warn her to step aside. They followed her instructions as if it were the most natural thing in the world.

For the Germans, whose lives had been defined by men barking orders, it was like watching gravity reversed.

They were herded onto the trucks with less roughness than they had known from their own sergeants. The boards under their boots were dry. The canvas overhead flapped in the wind. As the vehicles pulled away, Lisa caught sight of a faded poster on a warehouse wall.

A woman in a blue shirt, hair tied in a scarf, rolled up her sleeve and flexed her arm above the words: We Can Do It!

Lisa pressed her palm to the wooden slat and watched the poster shrink to a colored blur. “They let her show her arms,” she murmured, half to herself. “In Germany they’d call that shameless.”

The truck cleared the harbor area and rumbled into the streets of a small American town. Through the gaps in the canvas the women saw neat rows of houses, shopfronts with glass intact, and people walking the sidewalks unafraid. Women in dresses and coats carried bundles and grocery bags. Others pushed prams or walked alone, their backs straight, their heads uncovered even in the chill wind. No one hurried in fear. No one glanced nervously over a shoulder.

At a stoplight, a car pulled up alongside the convoy. Behind the wheel was a young woman with dark hair and a cigarette between her fingers. She tapped ash into an open tray and changed gears as casually as if she had been born doing it. The light turned green and she drove off, one hand on the steering wheel, smoke trailing out the window.

“Look at her,” Ruth said, craning to see. “Driving, alone…”

“In our town you’d hear talk for weeks,” another replied. “Here, no one even looks twice.”

They believed at first that this must be a special city, an exception the Americans had prepared to impress them. But as the days passed and trains carried them deeper inland, the same pattern appeared again and again.

In station after station, women in uniforms directed the flow of men and cargo. In depot yards, women drove forklifts and trucks, swung down from cabs with grease on their hands. Billboards showed smiling women in kerchiefs working on assembly lines. Newspaper headlines glimpsed through kiosk windows announced: WOMEN BUILDING PLANES, WOMEN REPLACING MEN ON FARMS.

They had grown up in a country that praised mothers as heroines but kept them out of the public square. In Nazi rallies, women marched in separate blocks, their virtues defined almost entirely by their capacity to bear sons. Even those who worked in offices did so in the shadows of men, their signatures legally second-class.

Here, on everyone’s lips and posters and radio broadcasts, was a different story.

By war’s peak, more than six million American women had entered the workforce. They built bombers, welded ships, packed ammunition, serviced vehicles, and ran government offices. The German prisoners didn’t know the exact figures. They knew only what they saw with their own eyes.

When the convoy finally ground to a halt in a processing camp somewhere in the Midwest, they half expected the spell to break. Within the fences, surely, the old order would reassert itself. Men with guns, men with files, men with power.

Instead, the first person they met at the registration table was Corporal Mary Henley.

Her khaki blouse was pressed, her hair curled neatly beneath a garrison cap. A metal pen gleamed against her chest pocket. She looked up as the line of women approached, her gaze level, expression unreadable.

“Welcome to the processing center,” she said in slow, careful German. “You will be registered, examined, and assigned to your quarters. Follow the painted lines on the floor. Keep your identity cards visible.”

Her tone was flat but not harsh. She didn’t shout. She didn’t call them “Krauts” or sneer at their uniforms. She simply did her job.

The women moved along the line like sleepwalkers. In a large hall, the clatter of typewriters rattled the air. Rows of American women in uniform sat at desks, fingers flying across keys as they transcribed names and numbers onto forms. Each thwack of a typebar sounded to the prisoners like a hammer striking another crack into their old certainties.

“So many women,” Ruth said under her breath. “They trust them with everything.”

Behind a folding screen, an army nurse waited with blood pressure cuffs and thermometers. She asked questions in halting German and checked tongues and pulses, eyes and ears. When one woman shivered in her undershirt, the nurse handed her a blanket without comment.

“Any illness?” she asked.

The prisoner shook her head automatically, trained by years of fear to hide weakness.

The nurse frowned. “You are thin,” she said. “Too thin. You will eat three times a day here.”

It was not a threat. It was a prescription.

Outside, in the yard between the barracks, American women drove jeeps from one building to another. They swung the vehicles around with practiced ease, boots hitting the pedals, hands relaxed on the wheel. They shouted jokes to one another in passing. No one told them to lower their eyes or mind their voices.

At night in the barracks, the prisoners lay on unfamiliar mattresses listening to unfamiliar sounds. Crickets in the grass. The distant hum of a generator. Somewhere beyond the fence, a radio played jazz. The brass and piano notes danced over the wire, less like marching and more like breathing.

“We were prepared for cruelty,” Greta wrote later in a notebook she kept hidden under her bunk. “We found order. We were prepared to hate. Instead, we were made to watch women live free.”

Within weeks, some of the women were working outside the camp under guard, part of a growing labor system the U.S. used to ease farm and factory shortages. They boxed rations in warehouses where women supervised them, or helped with laundry in hospitals run largely by female staff. On one farm, a woman in overalls named Helen showed them how to hitch a plow behind a tractor and laughed when they marveled at the machine.

“The land doesn’t care who drives,” she said, wiping sweat from her brow. “Only that it gets done.”

Every encounter piled another stone onto a growing cairn of evidence.

In American homes where some were trusted to work, they saw wives who controlled the family budget and spoke plainly to their husbands. They saw mothers reading books in quiet moments instead of scrubbing late into the night. They saw daughters planning to go to college instead of being told to plan for marriage and nothing else.

In a small town church, they watched women sing in the choir, play the organ, and stand up to speak about collecting clothing for European refugees. Their voices carried easily through the rafters. No one shushed them.

It was not that American women did not face limits or injustice. The German prisoners noticed contradictions too: racial segregation they found both familiar and shocking, hand-painted “Whites Only” signs that sat uneasily beside speeches about freedom. They saw black American women doing the hardest work for the lowest pay. They saw inequality threaded through the freedom.

But even with those faults, the shape of the society around them was fundamentally different from the one they had left.

In Germany, they had been told that their war was fought for “Kultur,” for a higher civilization. They had been locked out of that culture’s public voice. In America, they saw something more chaotic, more open, and somehow more alive.

“We thought culture meant marble halls and uniforms,” Ruth wrote in 1947, after she’d returned to a broken home in Bavaria. “Here I saw it meant a woman who could speak without asking permission.”

By the time repatriation came, and the trains rolled east again, many of the women stepped on board with an unexpected cargo: questions they could not easily set down.

What kind of Germany would they return to? What kind of women would they be allowed to be? Could they forget what they had seen: a corporal with a pen and a steady voice, a nurse who prescribed food instead of shame, a farmer whose strong hands gripped both plow and steering wheel?

Most never went back to America. Life after the war was hard, and in the struggle to find housing and work and enough food for their families, memories blurred.

Yet when their daughters grew, and later asked, “What was it like?” some of them chose to tell this part of the story.

One told her child about the first time she saw an American woman in uniform. Another described a kitchen where the wife spoke of her plans to study again after the men came home. A third, pulling a braid through the fingers of a granddaughter, said, “I did not know my own strength until I saw women who lived like it was normal.”

The war had taken homes, husbands, parents, and illusions. It had flayed their country down to rubble and dust. But from the far side of an ocean, in a place they had learned to fear by name, something had been handed back to them quietly: a vision of what they could be.

They had come to America as prisoners, expecting chains.

Instead, they saw women walking with their heads up, issuing orders that men obeyed, shaping their own work and families and futures. And they carried that image home through every checkpoint, across every border, and into every generation that followed.

In the end, it wasn’t a grand speech or a law that changed them most. It was the simple, ordinary fact of a woman standing at a table on a windy pier in New York Harbor, clipboard in hand, unafraid—and knowing, without anyone needing to say it, that she belonged there.

The end.

News

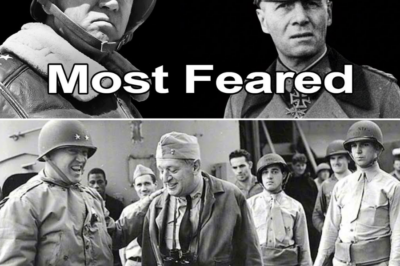

(CH1) Why German Generals Feared Patton More Than Any Allied Commander

In the spring of 1944, deep inside a smoky office in Berlin, German intelligence officers spread photographs, intercepted messages, and…

The day before my brother’s wedding, my mom cut holes in all my clothes, saying, “This will suit you better.” My aunt laughed, adding, “Maybe now you’ll find a date.” But when my secret billionaire husband arrived, everyone’s faces went pale…

The Silent Investor Chapter 1: The Art of the Cut “You’re not wearing that to the rehearsal dinner, are you?” My mother’s…

A millionaire woman kneels to dance with a poor boy: what happened next left everyone speechless…

The Silence After the Dance When Amanda got up from the floor, her legs were shaking. It wasn’t fear. It…

OUR DAUGHTER WAITS BY THE DOOR FOR HER DAD EVERY DAY—AND TODAY SHE NEARLY BROKE ME

It began as the tiniest routine. She’d finish her snack, wipe her fingers on that faded dress with the daisies…

The Millionaire Walked Into His Home Hoping For A Moment Of Peace — But When He Heard His Mother Whisper, ‘I’m Trying, Ma’am…

The Day My Perfect Life Cracked Open My name is Daniel Miller. On paper, I am the man everyone points…

(CH1) (1945) German‘Comfort Women’ Were Shocked When American Soldiers Finally Liberated Them

On the morning of April 7th, 1945, the war arrived in Alen-Grabow with the sound of engines, not bombs. Dawn…

End of content

No more pages to load