On the last raw mornings of October 1944, the war finally overtook Anna Vogel.

She had spent two days without sleep in a ruined field hospital somewhere near Aachen, packing bandages onto wounds that would not close, listening to artillery walk closer and closer through the night. The canvas roofs had long since given up; rain came straight through, turning blood, dirt and morphine into one sticky, freezing paste. When the shelling stopped, the silence felt worse than the noise. Everyone knew what it meant.

Surrender.

Anna was twenty-seven years old, a German nurse who had imagined herself tending children and elderly women in Cologne. Instead she had learned how to cut uniforms off shattered bodies with numb hands and how to keep her voice calm while telling boys half her age that no, their legs could not be saved. She had grown up on radio speeches about honour and sacrifice, about the duty to fight to the end. In the Wehrmacht briefings they never used the word “defeat.” Now, as olive-green trucks rolled over the muddy field and men in unfamiliar helmets spread out among the tents, the word sat like a stone in her throat.

She still carried a pistol, a ridiculous little thing tucked inside her coat, not to shoot the enemy but to avoid falling into their hands. The stories had been relentless: Americans would rape you, mutilate you, maybe cut your throat for sport. Nazi posters had shown crude cartoons of Jewish-American soldiers strangling blonde German women. Better a clean death of your own choosing than capture.

So when an American sergeant in a mud-stained field jacket knelt beside her and said, in halting German, “Bleiben Sie ruhig… you are safe now,” it did not register as kindness. It registered as a lie.

They took her bag, shook out the contents – bandages, a dog-eared Bible, a folded letter from her mother – and, to her surprise, handed everything back. No boots swung toward her ribs. No mocking laughter. Just a brisk wave toward the barn that had become a temporary holding area. Straw on the floor. Tin cups of water. Wariness in every eye.

“They’re feeding us,” a clerk whispered.

“It’s a trick,” someone answered.

Within twenty-four hours, Anna and a group of other female auxiliaries were on the move again, this time in the back of a larger truck. The field hospital, so permanent in her exhaustion, was already fading behind them. Beside her, a girl from signals clutched a rosary and muttered prayers. The road east had vanished; the road west led to a port she had only ever seen on maps.

At Le Havre the scale of her army’s collapse suddenly had mass and colour. Lines of gray-green uniforms stretched toward the harbour cranes, funnelled onto ships under the watchful eye of American MPs. She saw boys in their teens, men with white hair, tank crews with grease still ground into their fingers. In the distance a brass band tried to play above the churn of diesel engines. It all looked absurdly orderly compared to the chaos she had left.

On the transport ship, she heard, for the first time, the phrase “Geneva Convention.” An American officer explained through a translator that as prisoners of war they would receive food, shelter, medical care. The words meant almost nothing to Anna. Her own army had signed documents too, and she had seen how little the paper meant when things went bad. Still, the hot coffee in the tin cup tasted real enough.

Somewhere in those gray days the fear began to change shape. It no longer had the sharp edge of imminent violence. It became a dull, gnawing confusion. The enemy kept failing to act like the enemy.

When the ship docked on the American coast, she stood at the rail with hundreds of others, looking at a shoreline that might as well have been the moon. The docks were intact. Warehouses stood in neat rows. There were no bomb craters, no burnt-out trams, no shattered windows hastily covered by blankets. It was like staring into a world where the word “war” meant something entirely different.

On the pier, military police formed them into ranks and marched them toward a low building that smelled of soap and hot coffee. Inside, they were photographed, checked for lice, asked if they were wounded. Anna froze when she saw the examining doctor was a woman. In the Germany she knew, women in uniform were clerks, nurses, typists – never the one giving orders with a stethoscope. The doctor smiled like it was nothing and murmured, “You are safe now, Fräulein,” in reasonably decent German.

Safe. The word kept returning like an echo.

After a few days, a train carried them inland. The continent rolled past in segments: factories untouched by bombs, endless farms, distant mountains with snow clinging to their shoulders. At night, a guard came through the carriage and handed her an apple. It was so unexpectedly bright and cold in her hand that she almost dropped it. She hadn’t tasted fruit in months.

The train stopped at a place called Fort Douglas, in Utah, a name that felt like sand in her mouth. Barbed wire, watchtowers and long wooden barracks made clear that this was still a prison. But as Anna stepped down from the carriage, chilly air biting her cheeks, the first thing she noticed was the smell.

Bread. Warm, yeasty, unbelievable.

Inside the camp, everything ran on rules. There were timetables instead of shouted orders, regulations instead of threats. At roll call the guards counted briskly and moved on. No one used the butt of a rifle to hurry anyone up. After she and the other women had been assigned to a separate compound, they were taken to a washroom with actual running water and told to clean up. Soap, towels, plain PW-stamped clothing.

Her first night in the barracks she lay stiff on the narrow mattress, listening for the snap she had been waiting for since her capture: the moment the mask dropped and the cruelty began. Morning came instead, with oatmeal and boiled eggs and a coffee so weak it barely coloured the water, but hot all the same.

It was disorienting. She had been prepared for hatred, not for decency. Suspicion, not fairness.

The camp had a canteen where prisoners could spend the scrip they earned on work details. Cardboard tokens traded for bits of chocolate, cake on Sundays, tinned peaches. The sight of small luxuries on shelves, with price tags that prisoners could pay, felt at first like mockery. It became, slowly, something else: proof that these people believed obligation didn’t vanish just because the person in front of you wore the wrong uniform.

One afternoon, while lifting a tub of wet laundry, her hip flared with sudden, searing pain. The half-healed bruise from a collapsing wall back near Aachen had always been there, a dull throb she ignored. Now her legs buckled and the tub sloshed dirty water across her boots.

A guard saw. “Infirmary,” he said simply.

The word scared her more than she wanted to admit. In the Reich, hospitals for the weak could be final destinations. But the pain was too bad to refuse. She let herself be led to a squat white building near the fence. Inside, the air was crisp with disinfectant.

Ellen, the nurse, took one look at the way she sat and shook her head. X-rays followed – a rattling machine, a cold plate against her back, ghostly pictures of her bones pinned up to a light. The doctor traced a faint line with his fingertip.

“Hairline fracture,” the translator relayed. “Not dangerous, but it will hurt if you keep pretending it’s not there.”

They sent her back to the barracks with a bottle of pills and orders to avoid heavy lifting. Ellen produced a cushion – canvas stuffed with something firm but forgiving. “For when you sit,” she said, like a mother tucking a pillow under a child. The cushion went with Anna everywhere, a quiet little symbol of something she still couldn’t put a name to.

A German soldier under similar strain, she knew, would be told to keep marching.

Days settled into a rhythm. Work in the laundry. Roll call. Simple meals. Sunday concerts. English lessons taught by a prisoner who’d once studied in London. There were arguments in the barracks, too – about guilt and blame and whether any of this kindness was genuine. Some of the women believed it was all a calculated show for visiting inspectors. Others, like Anna, who spent time in the infirmary and saw the way staff treated their own wounded and the German ones exactly the same, began to suspect it was real.

“Why do you help us?” she asked Clara, the translator, one day, as they sat on the steps watching an American cook teach a prisoner how to flip pancakes.

“Because my brother is fighting in Italy,” Clara said. “If he was captured, I would want them to treat him like this, too.”

It wasn’t a grand speech. It didn’t need to be.

Letters home started to arrive just before Christmas. Her mother’s script, painfully familiar on flimsy paper: Cologne in ruins, her brother missing, food rationed to almost nothing. Anna read it at the edge of her bunk with the cushion under her and felt her stomach twist. She had been eating oatmeal and jam while her family boiled potato peels. Survivors’ guilt, the Americans called it later. At the time it was just a heavy, ugly feeling.

She helped more at the infirmary after that. Folding sheets, holding hands, writing letters for wounded men who couldn’t write themselves. Through Clara, she asked the nurses questions about hospitals in the States, about how they trained, about why there were so many women in positions of responsibility. In Germany, women were expected to serve, not to lead. Here, they ran entire buildings.

“When this is over,” Sergeant Moore, the supply sergeant, said once, wiping her hands on her trousers after hauling boxes of winter coats into the women’s compound, “we want to be able to say we stayed human.”

The phrase lodged in Anna’s mind like a stitch.

By spring 1945 the war in Europe was over. Flags dropped at half-mast, and the guards read the news aloud: Hitler dead, Berlin fallen, unconditional surrender. Some prisoners cheered. Others slumped as if struck. Anna simply sat on her bunk and stared at the fence.

The Americans did not gloat. There were no bonfires or jeers. Work details continued. Bread got a little better. Red Cross teams came through with more supplies. And slowly, the camp began to empty. Men and women went home in waves, carrying small bundles of belongings and the weight of what they had seen.

When Anna’s turn came, the same cushion Ellen had given her over a year before was one of the things she packed. It was ridiculous, a lump of stuffed canvas. But to her it had come to stand for the moment everything she’d been told about the enemy had cracked.

The trucks rumbled back east, through American towns with intact houses and supermarkets brimming with food. At the port, the crates they walked past bore stencilled words in English – FLOUR, MILK, PENICILLIN – bound, now, for a broken Europe.

Back in Germany, rubble greeted her. Streets she had played in as a child were now heaps of brick. Cologne’s cathedral spires still stood, improbably, over a sea of ruins. Her mother lived in a makeshift shelter with three other families, cooking thin soup over a shared stove.

“You look healthy,” her mother said, half relief, half accusation.

Anna couldn’t explain what it meant to be a POW in a camp that followed rules. She tried, haltingly, to describe the infirmary, the way the Americans had stuck to their Geneva books even when they were tired and angry. Some people believed her. More didn’t.

“You were fed by them while we starved,” a neighbour said once, bitterly. “Maybe you’ve forgotten who the enemy is.”

She hadn’t forgotten. She simply no longer believed that the labels told the whole story.

Work was scarce. Her fluency in English got her a job with the Allied administration, at first relaying lists, then translating in meetings. She watched American officers argue with German mayors about ration cards, housing allocations, rebuilding sewer lines. She saw them enforce rules not just on Germans, but on their own troops when they stole or misbehaved.

It looked, she realized, very much like the camp, scaled up: structure and fairness as tools, not decorations. Mercy with a spine.

When a visiting American doctor asked at a town meeting for volunteers to train as nursing aides in German hospitals, Anna’s hand went up almost without her thinking about it. She found herself back in wards that smelled of carbolic and sweat, this time in a white apron instead of a Wehrmacht uniform. She washed the faces of German children with rashes, steadied old men with coughs. Sometimes, as she bent over a bed, she’d catch a glimpse of a GI cap at the door and remember Utah.

On one of those days, a transport from a displaced persons camp arrived. The patients on the stretchers were not German. They were Polish, French, stateless Jews in clothes that hung off their bones. Some had camp numbers still visible on their forearms. Anna helped ease them onto beds alongside everyone else.

“Why are we treating them?” a local nurse whispered.

“Because they’re patients,” Anna replied, surprised by the certainty in her own voice. “That’s all.”

Years later, when she tried to explain to her children why she booked a trip to America, she told them she wanted to see where the world had turned upside down for her. Fort Douglas had been decommissioned by then, its barracks turned into exhibits and offices. The wire was gone. Visitors strolled where the guard towers once stood.

In the small museum, behind glass, there was a photograph of a group of German women in plain camp clothes, standing in front of a barracks in the snow. One of them looked very much like the girl she had been: thinner, wary, already beginning to let go of one set of beliefs and not yet sure what to replace them with.

A young guide in a crisp shirt told the group how many POWs had been held there, how the U.S. had ratified the Geneva Convention, how it had fed and housed and paid its prisoners. He spoke about training courses, hospital wards, vegetable gardens. He didn’t know he was speaking about her life.

After the tour, Anna stepped outside into the sharp Utah light. The flag snapped in the wind above her. She thought of the first time she had seen that flag from the ship, and how it had filled her with dread. Now it meant something else entirely.

They had won the war with fire and steel, yes. With bombers and tanks and prodigious industrial output. But they had also won it, she understood now, with blankets, with rules, with the stubborn insistence that even an enemy’s feet were worth saving.

Mercy had been their strangest weapon. And it had worked.

News

(CH1) Admirals Called Her Chalk Trick “STUPID” – Then It Saved 48,000 Lives

At 6:43 on a raw March morning in 1943, a nineteen-year-old woman stood in a cold Liverpool basement and looked…

(CH1) How One Girl’s “SILLY” Chalk Trick Made German U-Boats Sink 3 Times Faster

At 6:43 on a cold Liverpool morning in March 1943, a nineteen-year-old woman stood in the middle of a painted…

(CH1) How One 14-Year-Old Girl’s “Crazy” Bicycle Trick Killed Nazi Officers

In the history of warfare, death usually wears a uniform. It arrives with the thunder of artillery, the scream of…

(CH1) How One US Woman’s “Shopping Trips” Saved 7,000 Allied Pilots from Nazi Prisons

March 2nd, 1943. Marseille. The coded telegram was short, cold, and devastating. “Pat has fallen.” Four hundred kilometers away, in…

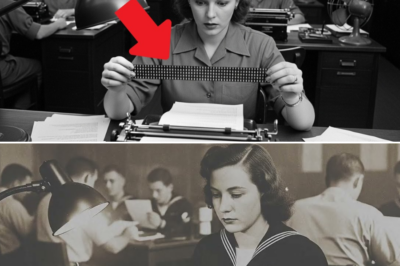

(CH1) How One American Woman’s Torn Typewriter Ribbon Saved 3,000 Lives and Sank 4 Japanese Carriers in 5 Hours

At 4:17 a.m. on May 25th, 1942, the ocean was still dark outside Honolulu, but inside the Fleet Radio Unit…

(CH1) How One Female Sniper’s “CRAZY” Trick Took Down 309 Germans in Just 11 Months

5:47 a.m. – August 8th, 1941. Belaya Tserkov, Ukraine. Twenty-four-year-old history student Lyudmila Pavlichenko crouched behind a pile of shattered…

End of content

No more pages to load