The convoy rattled through what was left of Germany.

Houses that had once been bright with geraniums and lace curtains now stood as shells, half-walls and dangling beams. A church steeple still pointed at the sky, but the nave beneath it was gone, open to the gray April air. Captain Robert Harrington leaned one hand against the canvas side of the medical truck and felt every rut the war had carved into the road shudder through his bones.

Behind him, men moaned on stretchers lashed to the truck bed. The air smelled of sweat, blood, disinfectant, and exhaust. He could tell, even without looking, who was drifting toward sleep and who was drifting toward shock. Eighteen months in Europe had given him a sixth sense for those things.

It was another sound that made him turn. A sharp cry in German, high and ragged, cut across the low groans. A woman’s voice.

He pushed the canvas flap aside.

Near the rear gate, a figure in a torn gray uniform had been standing, one hand gripping the metal frame. Harrington saw her knees buckle as if someone had cut her strings. She crumpled to the wooden planks. Her cap rolled away, bumping against a crate.

“Medic!” Private James Patterson shouted. The boy’s voice cracked with panic.

Harrington was already moving, his medical bag in his hand before he realized he’d grabbed it. The truck lurched and he grabbed at a rope to steady himself. When he reached her, he saw the blood—a dark stain spreading across the coarse fabric of her tunic, just below the ribs.

She lay on her back, eyes open, staring at the sagging canvas above. She couldn’t have been more than thirty, though war had carved deep lines around her mouth. Her blonde hair was yanked back in regulation severity, but loose strands clung to her damp forehead.

“Stop the convoy!” Harrington shouted toward the cab, knowing even as he did that it wouldn’t happen. They were threading through territory that had been contested that very morning. Stopping one truck meant stopping the whole column—turning fifteen vehicles into perfect targets. The driver had his orders. They didn’t mention halting for a German prisoner.

The engine note didn’t change.

Harrington knelt. His knees slammed into the boards. He barely felt it. He cut away the cloth over the wound with scissors from his bag. Blood welled up, more than he had thought at first, spreading in a hot wave. The smell hit him—iron and something deeper, the smell he associated with ruptured organs and failing time.

“Sir, Sergeant Morrison says we can’t waste supplies on prisoners,” Patterson stammered. “We’ve got our own—”

“Patterson,” Harrington snapped without looking up, “if I don’t act now, she’ll be dead before the next mile marker. Get me light. All of it. And every clean rag in this truck.”

Patterson moved. The other passengers pulled back, pressing against the walls, trying to make space that didn’t exist. An old German woman in a battered coat clutched a suitcase to her chest and watched with huge, frightened eyes. Two American soldiers with bandaged arms sat up straighter on their stretchers, their rivalry with the gray uniform on the floor swallowed by something older and simpler: the sight of someone dying.

“Ma’am, can you hear me?” Harrington asked. “Können Sie mich hören?“

Her eyes shifted, found his face. She nodded—a bare tremor. Her lips moved. He bent closer. Her breath was shallow, scented with fear and old coffee.

“Bitte,” she whispered. “Please.”

He’d heard that word in every language war offered. On operating tables. In cellars. In the filthy corners of bombed-out basements. It was always the same plea.

The truck hit a crater. The floor jumped under his knees. The scissors slipped, nicking her skin. She didn’t flinch. Her face had gone beyond white toward gray.

He checked the papers clipped to her tunic: Schrader, Margarete. Communications officer. Thirty-two. Captured near Kassel three weeks prior.

She looked younger.

“Patterson,” he said, “hold that lamp right over her. Davey, you—” he pointed at a corporal wedged near the wheel well, “—you help me steady her. Nobody moves unless I tell you to.”

He pressed his stethoscope against different quadrants of her abdomen. The sounds he heard—or didn’t hear—made his gut tighten. Rigid belly, guarding, diminished noise on the left. Internal hemorrhage. Something deep had split open.

He squeezed her shoulder. “Margarete,” he said, forcing his high-school German into the shape of reassurance. “Ich muss operieren. Hier. Jetzt. You understand?”

Her eyes brimmed, but her gaze was steady. Her hand shot up unexpectedly, fingers clamping around his wrist with surprising strength. She pulled his hand toward her belly.

“Baby,” she gasped in halting English. “Vier Monate. Four months. Please… Baby.”

He was a father. He had a seven-year-old boy named Bobby, a daughter, Sarah, and another child he had never seen—born while he was already in Europe. His wife’s last letter had mentioned tiny fingers and a shock of dark hair.

Two patients now, he thought. One on the wrong side of a war and one who’d never seen daylight.

“Hold her hand,” he told Patterson. “Talk to her. Keep her awake if you can.”

The boy’s fingers wrapped around hers. His other hand shook as he held the flashlight.

Harrington laid out what tools he had. Scalpels, hemostats, suture, saline. All cleaned by field standards but nothing like sterile. No ether. No chloroform. Only morphine ampules that could blunt the pain but might depress her breathing too much.

He couldn’t give her darkness. He needed her with him.

“This will hurt,” he warned. “Es wird weh tun. I’m sorry.”

He didn’t wait for permission. The first cut drew from her a sound that belonged in no language—a raw, rising wail that stuttered into gasps. Her body arched. Patterson clung to her hand, murmuring nonsense and prayer in equal measure.

The truck veered right, then left. Harrington’s blade tracked off its line but his fingers corrected. Muscle memory. Years in crowded emergency rooms, church basements, and barns turned into surgical theaters had taught him something: precision wasn’t a luxury. It was survival.

Her abdomen opened under his hands. Blood and dark clots spilled into the shallow basin he’d improvised from a mess tin. Deep inside, everything was displaced, swollen, wrong. He saw it then: the spleen, a mangled mass, half black, half oozing. An old injury, maybe from a beating or a fall, held together by nothing but chance and will until the jolt in the truck had finished what time had started.

She should have died days ago, he thought.

He clamped where he could, stuffed towels into cavities for makeshift suction, worked by feel when the truck’s bouncing blurred his vision. Davies blotted instead of wiped, as ordered; even a small misstep could tear what he was trying to save.

“Pulse?” he asked.

“Fast,” Davies answered, fingers at her throat. “Too fast. Weak.”

Tachycardia. Her heart pounding against the growing emptiness in her vessels. He murmured encouragement to no one in particular. “Come on. Stay with me.”

The engine note dropped. The truck slowed. Then, abruptly, it jolted to a full stop. Outside, voices shouted, boots thudded, orders flew. A checkpoint. An argument. Paperwork.

“Do not move,” Harrington said. “None of you.”

For the first time since he’d cut her, the floor wasn’t shifting under him. He took the gift.

He worked faster now, but not hastily. He tied off the splenic artery, pinching off the main line feeding the ruin. He cut the organ free like something rotten from a tree and packed the hole it left with gauze, hoping his knots would hold through the next pothole. There was no salvaging the spleen. Only the woman and the child.

“Baby?” she whispered once more, the word more air than sound.

“Herz schlägt,” he told her. “Heart’s beating. But I need you to fight.”

He could not promise her more than that.

When he tied the last suture, the truck roared back to life beneath him. The abrupt forward surge sent him sprawling, instruments skittering across the boards. He lunged to gather what he could, then crawled back, one hand braced on her shoulder as much for his balance as for her.

The wound was closed. For now, the bleeding was stopped. Infection, sepsis, and everything he couldn’t control would come later. Right now, she had a chance.

For the next fifteen hours, “chance” was all they lived on.

He and Patterson took turns checking her pulse, her pupils, her breathing. He rationed water in spoonfuls, watching her throat work as she swallowed. He flushed the wound as best he could. He dusted sulfa powder into the incision, knowing it was a flimsy shield against the millions of invisible enemies already creeping toward their handiwork.

Once, near dusk, she surfaced from the gray.

“Durstig,” she croaked.

“Small sips,” he warned. “Langsam.”

She sipped and then clung again to Patterson’s hand. Her eyes found Harrington’s face.

“Baby?” she asked.

“Still there,” he said. “Still fighting.”

She closed her eyes. A tear leaked from the corner and ran into her hair.

Outside, the countryside rolled past in ruined browns and blacks. Barns collapsed into themselves. Rows of fruit trees shattered like bones. Refugees trudged along the roadside, burdened with what little their lives had been reduced to: bundles, children, silence.

Finally, at dawn, the convoy pulled into a courtyard ringed by broken schools. A red cross flag hung from what had once been a gymnasium. They had reached the medical station.

Hands lifted her this time. Not rough, not gentle—just efficient. Onto a stretcher. Through doors that had once opened onto classrooms full of children reciting Latin verbs. Harrington followed, shouting a briefing as they went.

“Splenectomy in the field. Massive blood loss. Four months pregnant. No transfusion en route. She needs blood and antibiotics.”

Major Sullivan met them halfway, hair sticking up at odd angles, stethoscope around his neck.

“You cut her open in the truck?” he asked, incredulous.

“On the floor,” Harrington replied. “With half the instruments and none of the ether. I did what I could. The rest is yours.”

They moved her into a real operating room: tiled floor, overhead light, proper tables. For a moment Harrington hated the room—the cleanliness of it, the order. For a moment he wanted to kneel on that truck floor again where skill and need had been the only rules. Then he backed away, surrendering her to the system that could do more for her now than he could.

Sullivan looked at him over the mask. “You might have given her a chance,” he said. “Most men would have let her die.”

“I didn’t have the right kind of eyes for that,” Harrington said.

Sergeant Morrison found him outside later, while Harrington was smoking a cigarette he didn’t remember lighting.

“You know I should write you up,” Morrison began. “Using scarce supplies on a Kraut prisoner while our own boys—”

“Yes, you should,” Harrington agreed.

“—but I spoke to the colonel,” Morrison finished. “And to Sullivan. They think what you did was… exceptional.”

“Exceptional stupidity,” Harrington said.

“Exceptional courage,” Morrison corrected. “They’re putting you in for a commendation. Hell of a thing, Doc. Cutting in a moving truck. I wouldn’t have the stomach to watch it, let alone do it.”

Harrington thought about the three American boys Morrison had told him about—the ones who had bled out last week for lack of plasma. There was no tidy way to balance those scales.

“I didn’t do it to be brave,” he said. “I did it because she was dying in front of me.”

“Sometimes,” Morrison replied, “that’s what bravery is.”

He went to see her later that day.

The ward smelled of carbolic and boiled linen. Rows of cots lined the walls. Men lay under thin blankets, faces pale as candle wax, arms and chests and legs wrapped in gauze. The war had left its marks in straight lines and jagged scars.

She lay among them now, one more pale face.

“Captain Harrington,” she said when he approached. Her voice was soft, but it carried. “They tell me you’re the one who cut me open like a fish.”

“That’s one way of putting it,” he said, pulling a chair bedside. “I prefer ‘surgically intervened.’”

“They say you saved my life,” she went on. “And the baby’s.”

“‘Say’ is a strong word,” he answered. “You’re alive, and that’s something. The rest will depend on time and luck.”

“I had neither before you picked up your knife.” She touched her abdomen, fingers tracing the line of his sutures beneath the bandages. “It hurts.”

“It will. Healing hurts.”

She watched him silently for a moment. “Why?” she asked. “Why do that for me? I am German. Your enemy. I worked in signals. I sent messages that killed your people. Why save me?”

He met her gaze. There was no easy answer he could stomach.

“Because you were bleeding in front of me,” he said finally. “Because I’m a doctor and that’s what we do. Because if I start deciding who deserves to live, I won’t know where to stop.”

She seemed to turn that over, weighing the words.

“My husband is dead,” she said quietly. “My country is dead. Everything I believed in is dead. But this…” She laid her hand flat over the small swell of her belly. “…this is not dead. This is the only thing that is still new. You gave him a chance. Whatever else happens, that cannot be taken away.”

He didn’t correct her pronoun. It didn’t matter.

The war ended three weeks later.

Harrington heard the news over a distorted loudspeaker while he was rinsing his hands at a metal sink: Germany had surrendered. The ward erupted in cheers and quiet sobs. Nurses hugged one another. A man with his leg in traction tried to sit up and his neighbor hauled him back down with a laugh.

He thought of Margarete in the other building, healing slowly. Thought of the baby whose heart had thudded against his fingers while he tied off her splenic artery.

He saw her twice more before she left: once when she was strong enough to sit up and once when she was preparing to be moved to a displaced persons camp in Bavaria.

“Will you go back to Kassel?” he asked.

“There is no Kassel left,” she replied. “Only rubble. I will go where they send me. When the child comes, we will see.”

What he remembered most from that last meeting wasn’t her words. It was the way she stood by the window, one hand on the frame, the other on her side, looking out at the spring sky with something that was not quite hope and not quite despair. Something in between.

“Thank you,” she said once more before they took her away. “For seeing me as something other than the uniform I wore.”

“I’ll try to do that more often,” he replied.

In 1947, back in Pennsylvania, he opened a letter forwarded through military channels. The handwriting was neat and careful; the paper was thin and worn from travel.

Dear Captain Harrington,

You may not remember me, but I am the German woman whose life you saved in a truck in April 1945.

My son was born in August of that year. He is healthy, strong, and too clever for his own good. I named him Klaus, for his father, and Robert, for you.

Life here is hard. Our town is rubble. Food is scarce. But every time I look at my son, I remember that in the worst moment of my life, when I had every reason to believe my enemy would let me die, an American doctor chose to help me instead.

I tell this story often. Some do not want to hear it. They prefer their hatred simple. But others listen. Perhaps that matters.

With gratitude,

Margarete Schrader

He sat for a long time with the letter in his hand. Then he went to his desk and wrote back.

He told her about his own children, about Bobby’s baseball games and Sarah’s books, about little Rob dribbling peas onto the floor. He told her that the surgery haunted him sometimes, not as a nightmare, but as a strange, bright memory of clarity in a muddy war.

You ask why I did what I did, he wrote.

The simple answer is that you were my patient. War draws lines between us, but medicine erases them. For a few hours in that truck, you were not German and I was not American. You were in trouble and I knew how to help.

I’m glad Klaus Robert is well. I’m honored you chose my name. Tell him, when he is old enough to understand, that his life is the result of many hands and choices. His mother’s courage, a private’s kindness, a medic’s habit of carrying extra gauze, and a decision, made quickly in a noisy truck, that a stranger’s life mattered.

That is how the world gets better, if it ever does: small decisions that say, over and over, we will not let each other fall.

Sincerely,

Robert Harrington

The letters continued, sporadically, over decades. They traced two lives rebuilding out of the same war from different sides of the ocean. Photographs came: a boy with serious eyes wearing too-big hand-me-downs in a bombed-out courtyard; a teenager in a school uniform; a young man in a lab coat.

In 1963, a lean twenty-year-old with those same serious eyes—and a slight limp from a childhood accident—stepped off a plane in New York as part of a student exchange. He took a bus to Pennsylvania and knocked on the door of a modest house with a brass plaque that read: R. Harrington, M.D.

When Harrington opened the door, he was older than the captain in the truck, his hair more gray than brown. But his eyes were the same.

“Dr. Harrington,” the young man said in accented English. “I am Klaus Robert Schrader.”

They shook hands on the porch. Harrington felt, absurdly, like he was touching the ghost of that impossible morning brought to life and given flesh.

They spent two days together. They drove through the countryside. They ate meals with Harrington’s family, the German guest sitting at the table among grown American children who had heard the story their whole lives. They talked about medicine, history, forgiveness.

“My mother always said you reminded her that being a doctor means more than treating your own side,” Klaus told him. “She says you helped her remember her duty as a nurse is to life itself, not to a flag.”

“Your mother reminded me of mine,” Harrington answered. “She reminded me why I picked this profession before uniforms and ranks got involved.”

On his last evening, Klaus said, “She wanted me to tell you that what you did that day changed more than two lives. She has spent years telling your story. Some people have listened. Some have changed how they see Americans, how they see enemies. So perhaps your surgery was the first stitch in a much larger wound.”

Harrington smiled sadly. “Then it was worth the cramped knees.”

He died in 1981, at seventy-three. There were flowers and hymns and eulogies about his decades of service as a small-town doctor.

Among the mourners was a middle-aged man who had traveled from Germany, a man who stood by the casket with his hand resting lightly on the wood.

“My mother sends her love,” he told Harrington’s widow. “She is too ill to travel. But she wanted you to know she never forgot your husband. She lived her life trying to be as kind to others as he was to her.”

Somewhere in Germany, a woman who had once screamed under his knife lay in a narrow apartment, an old scar puckered under her nightgown, a grown son at her bedside. Somewhere in Pennsylvania, Harrington’s grandchildren listened to the story their mothers and fathers told about a day in 1945 when a doctor refused to let the war decide who deserved to live.

April 14th, 1945 had been just another day in the war. There were skirmishes, artillery barrages, bombings, and a thousand nameless deaths.

And there was, inside the rattling dark of a truck, a small act of defiance against the simplest cruelty of war: the temptation to look away.

In the end, it was not a general’s strategy or a politician’s speech that connected the Harringtons and the Schraders. It was a hand on a wrist, a promise made over blood, a scalpel line drawn in hope.

This is what medicine is, Harrington would have said, if anyone had asked him to sum it up.

Not miracle cures. Not perfect outcomes.

Just a man with a bag of tools, seeing someone in pain, and kneeling on a rough floor to say: I will not let you die if I can help it.

News

(CH1) Admirals Called Her Chalk Trick “STUPID” – Then It Saved 48,000 Lives

At 6:43 on a raw March morning in 1943, a nineteen-year-old woman stood in a cold Liverpool basement and looked…

(CH1) How One Girl’s “SILLY” Chalk Trick Made German U-Boats Sink 3 Times Faster

At 6:43 on a cold Liverpool morning in March 1943, a nineteen-year-old woman stood in the middle of a painted…

(CH1) How One 14-Year-Old Girl’s “Crazy” Bicycle Trick Killed Nazi Officers

In the history of warfare, death usually wears a uniform. It arrives with the thunder of artillery, the scream of…

(CH1) How One US Woman’s “Shopping Trips” Saved 7,000 Allied Pilots from Nazi Prisons

March 2nd, 1943. Marseille. The coded telegram was short, cold, and devastating. “Pat has fallen.” Four hundred kilometers away, in…

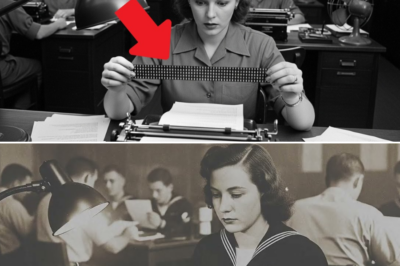

(CH1) How One American Woman’s Torn Typewriter Ribbon Saved 3,000 Lives and Sank 4 Japanese Carriers in 5 Hours

At 4:17 a.m. on May 25th, 1942, the ocean was still dark outside Honolulu, but inside the Fleet Radio Unit…

(CH1) How One Female Sniper’s “CRAZY” Trick Took Down 309 Germans in Just 11 Months

5:47 a.m. – August 8th, 1941. Belaya Tserkov, Ukraine. Twenty-four-year-old history student Lyudmila Pavlichenko crouched behind a pile of shattered…

End of content

No more pages to load