In December 1946, in a hushed courtroom in Nuremberg, a young German woman leaned toward the microphone and said a sentence that made several judges frown.

“The first thing they told us was, ‘Show us your feet.’”

The trial was supposed to be about gas chambers, extermination orders and mass murder. Yet here was a former Wehrmacht auxiliary, speaking calmly about boots and blistered soles. It sounded almost trivial, until she began to explain what those four words had meant in the last weeks of the war.

Her name was Greta. She had been a signals clerk, captured with a group of forty-six other German women near the Rhine in April 1945. Three days before her capture, she had been retreating ahead of the Red Army. By the time American troops surrounded their column, the women had walked more than 300 kilometres. Many of them could barely stand. None of them expected to live much longer.

Nazi propaganda had done its work well. For years they had listened to radio voices and read leaflets that warned of the same fate: if you fell into American hands, you would be raped, tortured and shot. Better to die by your own hand than endure that dishonour. They had seen those words pasted on village walls. They had repeated them to one another in bunkers and barracks.

On a cold, rainy day in early April, the women were herded into a long canvas tent in a makeshift prisoner-of-war camp by the river. The ground had turned to thick brown mud. Their uniforms were soaked through; their boots were little more than stiff, filthy shells around their swollen feet. The tent smelled of wet wool, sweat and fear.

They stood in line shivering, waiting for the blows to fall.

Instead, an American sergeant stepped in, rain still dripping from the rim of his helmet. He looked at them without evident anger, then spoke through a German-speaking interpreter.

“Boots off. Socks off. Show us your feet.”

For a moment, no one moved.

They had trained themselves for questions, even for physical abuse. No one had prepared them for this. Did the Americans intend to shame them, make them stand barefoot in the cold mud? Was this some new form of humiliation?

At the back of the tent, men with Red Cross armbands were setting up folding tables, lanterns and a small field stove. Basins appeared, then jerry cans of water. The scene looked less like a guardhouse than a rough medical station.

The oldest woman in the group, a thirty-four-year-old auxiliary called Hanna, decided someone had to go first. As a senior among them, she felt responsible for the younger girls, some only nineteen. She sat on a crude wooden bench and bent to untie her laces. The leather clung. When she finally prised the boot free, the sock underneath came with it, stuck to the skin. A sour smell spread through the tent.

An American medic knelt in front of her. He did not laugh. He did not look away in disgust. He simply examined her foot, then called for a basin and more light. Through the interpreter, he asked how long it had been since she had taken her boots off.

“I don’t know,” she said, embarrassed. “Weeks. We had to keep moving.”

One by one, the others began to comply. Boots thudded onto the ground. Damp, stained socks peeled away with little gasps of pain as skin came with them.

What the medics found under the wool confirmed what Germany’s own medical officers had been warning in reports for months: trench foot, the same affliction that had crippled thousands in the First World War, had come back with a vengeance in this final winter retreat. Nine out of ten of the women in the tent showed serious damage: whitened, soggy skin, deep cracks packed with mud, toes swollen to twice their size, patches of grey and black where circulation had died. One girl’s toes were so badly frostbitten that they were literally dead flesh she had been walking on.

When the medic reached Ingrid, a 23-year-old secretary from a signals battalion, he had to cut her sock away in strips. Her soles were so tender she felt nothing when he touched one darkened toe.

“How long have they been like this?” he asked.

“We marched and we marched,” she answered. “We were told, ‘Do not fall out. Do not stop.’ There was never time to take off our boots.”

The medics’ faces hardened, not in anger at their captives, but in professional alarm. Untreated, those feet would mean amputations, blood poisoning, death. In the cramped, unsanitary conditions of a prison camp, one case of gangrene could spread infection through dozens of people. Bacteria did not care what uniform you wore.

They sent for more supplies: warm water, soap, sulfur powder – the wonder drug of the day – and lengths of bandage. Sulfur, a sulphur-based antiseptic, was expensive. In 1945 it cost more than a private’s monthly pay for a pound. That afternoon, the U.S. medical team used roughly fifty dollars’ worth on this one group of German women. It was an odd investment, if you believed, as they did, that the war would soon be over and these were enemies.

The case that stayed with everyone in the tent, and later in Nuremberg, was Greta’s.

She had been resisting, pressing her heels into the mud as if refusing to surrender this last layer between herself and the enemy. When she finally complied, the medic saw at once that her feet were in worse condition than the others. The socks sheared away in bloody clumps. Underneath, the soles were pocked with tiny glints of glass.

Weeks earlier, in the chaos of the retreat, she had stepped through the shattered window of a shopfront. There had been no time to stop – the Soviet artillery was already in range. She had kept walking on the glass, day after day, until it became part of her.

The young medic who worked on her, Private Robert Johnson from Iowa, counted thirty-seven slivers of glass as he dropped them one by one into a pan. Some were near the surface. Others required small cuts to reach. Greta lay back on the bench, jaw clenched, determined not to cry out in front of the Americans.

As he worked, Johnson spoke quietly to the interpreter. He told a story about his sister back home, a child who had stepped on a nail the previous year. In wartime America, all the new antibiotics had been diverted to the military. The drugstore in their town had none left. The wound had infected. She had died.

That death, he said, was why he had joined the medical corps. He didn’t want anyone else – friend or enemy – to die of something that could be prevented with a careful hand and a bottle of antiseptic. When Greta asked, in slow English, why there were tears on his cheeks, that was the answer the interpreter gave her.

It was a small story, but in that tent it had the weight of a confession. Her own army had marched her on glass until her feet were raw meat. Her enemy, who had every reason to hate her, was kneeling in the mud and crying over those same feet.

By late afternoon the worst of the stench was gone. The tent smelled of iodine and soap. Basins of filthy water had been emptied and refilled countless times. The women’s feet, cleaned and dusted with sulfur, looked less like something from a trench horror photograph and more like human flesh, wrapped in strips of clean white cloth.

Then the nurses came.

They arrived in the early evening: American women in grey-green uniforms and white caps, carrying towels and enamel basins. They were officers and NCOs, some barely older than the prisoners. They moved down the line, kneeling in front of each woman in turn.

To many of the German women, who had grown up in Christian households, the image was jarring. In church they had heard the story of Christ washing his disciples’ feet. Servitude, humility, grace flowed in that direction: from the pure to the less worthy. Now the roles were reversed. Here were the victors, kneeling in front of the defeated, washing their wounds.

One former clerk later admitted that it broke something in her.

“I had learned to see them as monsters,” she said. “But monsters do not wash your feet.”

Not everyone in the tent welcomed it. Elsa, a nineteen-year-old former Bund Deutscher Mädel leader with neatly braided hair and the hard eyes of a zealot, recoiled as a nurse lowered her bandaged feet back into the water.

“This is for show,” she snapped in German. “For the newsreel. They want us weak and grateful so they can do what they really plan.”

The interpreter relayed her words. The nurse in front of her, Lieutenant Rebecca Mitchell, stood up slowly. She had a tired face, the kind that had seen more than one war. Without a word, she rolled up her left sleeve.

Faint blue numbers were tattooed on her forearm.

A-734.

Ingrid, watching from the next bench, stared. She had seen cartoons of such marks in foreign newspapers before the war; Nazi officials had always dismissed them as Allied lies.

“My name was Rivka before,” the nurse said in accented German. “I was born in Poland. The Germans gave me this number in Auschwitz.”

Through the interpreter she told them, briefly, what that meant. Her parents, her sisters, her grandparents – all had died behind the barbed wire and concrete of the camp. She had escaped before the end, made it to America, trained as a nurse and returned across the Atlantic in a different uniform. She had every reason to hate every grey-green collar she saw. Instead, she knelt down again in front of Elsa and lifted her heel into the basin.

“I wash your feet,” she said quietly, “because I refuse to become what was done to us.”

The tent was very still. Outside, somewhere, artillery thumped. Inside, water lapped against enamel, and a woman from Auschwitz bathed the feet of someone who had once led girls in singing songs about the purity of the Volk.

Later research by Allied medical units would show that, of the German women auxiliaries captured that spring, a large majority said it was this moment – the washing, the bandaging, the unforced kindness – that first cracked their belief that the enemy was inhuman.

War ended. The tent came down. But the consequences of those four words – “Show us your feet” – did not.

Six months later a very different smell filled the corridors of a hospital outside Frankfurt: carbolic soap, boiled linen, a hint of cigarette smoke. Germany lay in ruins. Cities had been flattened, food was scarce, and disease was stalking the displaced. Allied forces, now occupiers as well as victors, had hospitals to run for their own wounded and for civilians.

Walking down one of the wards, pushing a cart loaded with dressings and bottles of disinfectant, Greta passed beds filled with men in unfamiliar uniforms. On one bed lay an American sergeant whose legs ended in bandaged stumps just above the knee, casualties of a mine outside Bremen. On the next lay a German teenager with shrapnel in his chest. Farther on, a Polish former forced labourer coughed weakly under a blanket.

“If you were sick, you were a patient,” she would say later. “That was all that mattered.”

She was there by choice. Allied records show that several thousand former German prisoners volunteered to work in medical units after the capitulation. Some cooked or cleaned. Others, like Greta, trained as auxiliary nurses. The same women who had once typed military orders now rinsed out basins and changed bandages.

Elsa was there too. Her braids were gone, replaced by a practical bun under a plain scarf. She sat in a windowless supply room, counting rolls of gauze and checking expiry dates on bottles of iodine. Someone had painted a sentence in German and English above the shelves: “Healing knows no borders.”

In pediatrics, Maria, who had once marched in uniform, gently wiped the faces of children with measles and malnutrition. It didn’t matter if their parents had been party members or anti-Nazis, slave labourers or refugees. The fevers were all the same.

Rebecca, the nurse with the tattoo, visited sometimes. Her American uniform did not hide the faded numbers on her arm. She still knelt when she had to wash filthy, cracked feet. When Elsa asked her one day why she had allowed German women into her ward at all, Rebecca answered without bitterness.

“I don’t trust what you were,” she said. “I trust what you might become.”

And then, in that cold stone building in Nuremberg, where prosecutors were trying to define the difference between ordinary guilt and extraordinary evil, Greta told the story under oath.

She described the mud and the fear, the order to remove boots, the smell when the socks came off. She described the young American medic who cried because he had lost his sister to an untreated foot wound. She described Rebecca baring her arm and kneeling with the basin.

The judges, who had heard so much about cruelty, asked why this mattered.

Because, the prosecutor said, it showed there was a choice.

The same Europe had produced Auschwitz and the Geneva Convention, gas vans and field hospitals. The same war had seen prisoners beaten to death in some camps and bandaged carefully in others. No one in that courtroom pretended that an act of mercy in a tent erased crimes committed elsewhere. But it did demonstrate that brutality was not inevitable, that even in the closing weeks of a devastating war, men and women still had the capacity to act differently.

In the decades that followed, the order “Show us your feet” became a footnote in medical journals and military ethics courses. It appears in an Allied report as an example of good practice in handling large groups of malnourished prisoners. It appears again in the transcript of a war-crimes trial, when a former enemy says that the first proof she had that the world was not exactly as her leaders had described it came in the form of a basin of warm water and a hand on her ankle.

For the women in that tent, those four words marked the moment their ideas about the enemy began to unravel. For some of them, they were also the first step toward a different kind of life: one in which the hands that had helped keep a machine of conquest running were used, instead, to lift the wounded and wrap clean cloth around a stranger’s feet.

In the end, that is what the story shows. Wars are fought with tanks and bombers, but they are defined just as much by what happens afterwards, in the mud of a prisoner-of-war camp, in the corridors of a hospital, in the quiet choices to see an enemy as a human being. And sometimes, all it takes to begin that change is a sergeant standing in a doorway, saying something no one expected to hear.

News

(CH1) Admirals Called Her Chalk Trick “STUPID” – Then It Saved 48,000 Lives

At 6:43 on a raw March morning in 1943, a nineteen-year-old woman stood in a cold Liverpool basement and looked…

(CH1) How One Girl’s “SILLY” Chalk Trick Made German U-Boats Sink 3 Times Faster

At 6:43 on a cold Liverpool morning in March 1943, a nineteen-year-old woman stood in the middle of a painted…

(CH1) How One 14-Year-Old Girl’s “Crazy” Bicycle Trick Killed Nazi Officers

In the history of warfare, death usually wears a uniform. It arrives with the thunder of artillery, the scream of…

(CH1) How One US Woman’s “Shopping Trips” Saved 7,000 Allied Pilots from Nazi Prisons

March 2nd, 1943. Marseille. The coded telegram was short, cold, and devastating. “Pat has fallen.” Four hundred kilometers away, in…

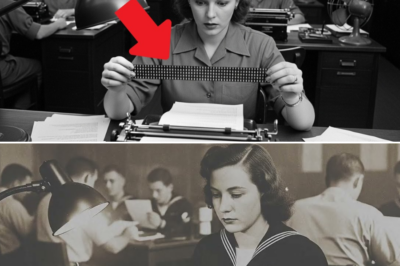

(CH1) How One American Woman’s Torn Typewriter Ribbon Saved 3,000 Lives and Sank 4 Japanese Carriers in 5 Hours

At 4:17 a.m. on May 25th, 1942, the ocean was still dark outside Honolulu, but inside the Fleet Radio Unit…

(CH1) How One Female Sniper’s “CRAZY” Trick Took Down 309 Germans in Just 11 Months

5:47 a.m. – August 8th, 1941. Belaya Tserkov, Ukraine. Twenty-four-year-old history student Lyudmila Pavlichenko crouched behind a pile of shattered…

End of content

No more pages to load