On March 15th, 1945, the war in Europe was nearly over, but inside a battered field hospital near the Bavarian town of Ammerbach, it didn’t feel that way.

The big guns along the front thumped faintly like a failing heartbeat. German units were surrendering in clusters. Towns were raising white flags or falling without firing a shot. But in this former schoolhouse turned field hospital, 177 women waited for something else.

They were nurses, clerks, and medical workers of the German Wehrmacht. They were not under orders. They were under siege—by fear.

They had heard the rumors. Everyone on the collapsing German front had. The Americans shoot women. The Americans rape nurses. The Americans don’t take prisoners. The stories traveled down retreating columns and through bunkers, whispered at night when the lights went out. None of them knew what was true. They only knew that the Reich was dying, and dying things rarely died cleanly.

So they prepared themselves the only way terrified people can.

Some of them drew lots, quietly deciding who would go first if it came to that—who would take the pills, who would use the hidden pistol, who would… spare the others. Some hid morphine or cyanide tablets in their pockets. Others wrote farewell letters no one would ever read, folded them into aprons or tucked them under mattresses.

They were not thinking about survival. They were thinking about how not to die screaming.

That morning, as the pale light crept through blown-out windows, it was not death that arrived. It was five American soldiers.

They did not come storming in with guns raised and faces twisted. They walked into the dim schoolhouse—now a hospital filled with stretcher cots and wounded men—carrying rifles at low ready, eyes scanning for threats.

Captain James Morrison was the first to step through the doorway.

He was 32 years old, a schoolteacher from Pennsylvania before the war—someone who had spent more time with chalkboards than with maps. He had seen enough combat to harden the edges of his heart, but not enough to hollow it out. He had watched good men die and bad men live. He had followed orders that haunted him. But he had held on to something stubborn and soft: an instinct to ask why before he pulled a trigger.

The orders for that day were simple: clear the field hospital, take any German personnel into custody, and move on. It was a task stamped in black ink: routine, necessary, impersonal.

The reality waiting inside was anything but.

There were no armed guards. No defensive positions. No weapons. Just rows of wounded German soldiers, their faces gray and slack on their cots. And above them, moving among them, clustered in corners and doorways, were women in bloodstained medical uniforms.

They froze when Morrison’s men entered.

One nurse’s hands shook so badly she had to clutch her apron to keep them still. Another sat on a crate whispering prayers in a monotone. A third had her fingers fisted into the stretcher rail of a boy who could not have been more than eighteen, as if holding on to him could anchor her to something solid.

Morrison had been in enough rooms like this to recognize terror. Not the adrenaline fear of battle—that sharp, bright thing soldiers carry into the first firefight—but a deeper dread, slow and dense, like water in the lungs. The kind that comes from expecting the worst and having no reason to expect anything else.

He saw it in every pair of eyes that met his.

Behind him, Sergeant Robert Hutchkins stepped in and stopped short.

He was 28, from Chicago, a medic who had spent the last three years working at the edge of life and death. He had dragged men out of shrapnel storms, held pressure on arteries, listened as lungs filled with blood. He had watched Americans die in his arms. He had watched Germans do the same.

The war had taught him one thing clearly: pain did not ask for a passport before it arrived.

When he looked at the women in the field hospital, he did not see uniforms first. He saw thin hands, red-rimmed eyes, a gait he recognized from civilian wards where mothers waited outside operating rooms. He saw his own sister in their faces.

He leaned toward Morrison, speaking just loud enough for his captain to hear.

“Sir… these are nurses. Clerks. They’re just doing the same job ours do. We can’t treat them like combatants.”

Morrison stood still for a long heartbeat, weighing more than orders in that silence.

He could have stuck to the book. The law of war required certain things and nothing more. Process prisoners, separate ranks, disarm, confine. He could have turned his back and carried out his orders with cold efficiency.

But he was a teacher before he’d ever put on a uniform, and teachers recognize what soldiers sometimes forget: some moments aren’t just tasks. They’re lessons. For everyone in the room.

He nodded once.

“Form up,” he told his men. “New plan.”

Five Men and 177 Women

That day there were five of them on the detail: Morrison, Hutchkins, Private William Chin, Corporal David Rosenstein, and Private Tommy Walker.

Chin was 23, the son of Chinese immigrants in San Francisco. He had grown up learning to live with the word enemy applied to his face by people who had never met him. He had seen the signs—NO CHINESE, NO DOGS. He understood, in his bones, what it felt like to be judged as less than human for reasons that had nothing to do with who you actually were.

When he approached a crying German nurse sitting on a crate, he did something simple and radical. He knelt.

Not above her. Not over her. Eye to eye.

In soft English and broken German, he asked, “Sind Sie verletzt? Are you hurt?”

She blinked, thrown by the gentleness. She pointed to her ankle, swollen and bound with dirty cloth. He made a mental note to let Hutchkins know.

Corporal David Rosenstein, 29, noticed something different.

Where Morrison saw fear and Hutchkins saw wounds, Rosenstein saw chaos. He had been an accountant before the war. His brain ran on columns, sequences, and systems.

What he walked into was a tangle of humanity. Nurses clinging to cots, clerks huddled in corners, wounded men moaning faintly, American rifles glinting at the door. Fear turned noise into chaos and chaos into panic. Panic, he knew, got people killed—even when no one was pulling a trigger.

So he did what he did best. He organized.

He set up stations: here, names and ages. There, medical triage. Over there, a corner for the women who could walk and work to help steady those who could not. He made sure everyone had water. He separated those who needed immediate treatment from those who just needed someone to explain what was happening.

He turned a potential stampede into something orderly, almost calm.

Private Tommy Walker—the youngest, only 19—turned it into something human.

He had grown up in a farming town in Tennessee, where neighbors brought casseroles when someone died and told stories on porches in the evening. The army had stripped some of that softness from him, but not all.

He spoke almost no German. But he had a smile that translated on its own.

As Rosenstein moved through his stations and Hutchkins assessed injuries, as Chin spoke quietly with the most frightened women, Tommy moved among the groups with canteens and awkward jokes that made no sense in translation but still made mouths curve at the corners.

He handed out water like it was hospitality, not ration. “Alles gut,” he’d say, mangling the phrase but making the intention clear. All right. You’re all right.

Those five men, in that broken schoolhouse, did something the manuals did not demand.

They chose a standard that went beyond minimum compliance and reached for something older and deeper than any regulation: the idea that how you treat the powerless reveals what you really are.

“Your War Is Over. Mine, Too.”

By midday, the women had been processed, catalogued, and assembled.

They stood in lines in the muddy yard outside, 177 uniforms in Luftwaffe and Wehrmacht gray, now stripped of insignia. Many clutched bags with their few belongings. Fear still lived in their posture, but the screaming panic of earlier had settled into something quieter.

Morrison stood in front of them. His voice, when he raised it, carried without shouting.

“You are now prisoners of war of the United States Army,” he said, through the interpreter. “You will be treated according to the Geneva Convention. You will receive food, shelter, and medical care. You will not be harmed.”

He paused, then added something more personal.

“Your war is over,” he said. “Mine, too, I hope. What happens next is up to all of us.”

The women did not cheer. They did not relax. Trust, for people who have lived on lies, does not come in a single speech.

But something shifted.

The lot-drawn pills stayed in pockets instead of mouths. The hidden pistols, in a few cases, stayed hidden and unused. Letters that had been written as farewells became something else—fragments of the past instead of the last words of a life.

Over the next five days, the journey to the prisoner-of-war camp in Utah took them across a collapsing Germany and a quiet America.

The first leg—by truck and train—carried them through their own ruined country. Past bridges lying in rivers, skeletal factories, towns with only chimneys standing where houses had been. Through each broken station, they saw civilians with hollowed faces and empty hands. It confirmed what they’d already guessed.

The Reich was not losing.

It had lost.

Then came the port, the ship, the Atlantic.

The transport to America smelled of steel, salt, and bodies. The hold was cramped, but not as they had feared. There were bunks. There were latrines. There were meals—even if they turned in some stomachs unused to eating regularly.

The five Americans stayed with them the whole way. No one ordered them to. Their official job could have ended at surrender and handover. But they kept showing up.

Hutchkins checked fevers and sores. Chin sat deck-side with women who stared too long over the railing, gently pulling them back with offers of coffee. Rosenstein kept track of who had eaten and who hadn’t, who might be slipping into despair. Walker kept talking, even when no one answered, filling the oppressive silence with someone else’s stories.

Morrison filed reports.

He did not write about heroism. He wrote about responsibilities. About 177 enemy women whose status under international law was clear and whose treatment would reflect on the country he served.

His words moved up chains of command, through quartermaster offices and medical services, through legal departments that would decide how these women would be classified and where they would go.

By the time the convoy rolled into Fort Douglas, Utah, the framework was already in place: separate barracks, clear rules, medical screenings, work assignments. No improvisation. No room for “what happens, happens.”

Morrison and his four men stayed long enough to make sure the transition held.

Only then did they let themselves be reassigned.

War Ends, Lives Continue

The story of those five men and those 177 women didn’t make headlines.

There were no photographers on hand to capture their arrival. No newsreel voiceover saying, “Today, American boys showed mercy.” The world was busy with bigger dramas: the fall of Berlin, the liberation of concentration camps, the looming war in the Pacific.

The kindness at Ammerbach and Fort Douglas went down on paper instead: reports, logs, names and numbers.

But kindness leaves traces.

Those traces showed up years later in places no one expected.

In Pennsylvania, where a high school principal named James Morrison insisted his teachers treat even the worst students as worth the effort.

In Chicago, where Dr. Robert Hutchkins quietly wrote off bills for patients who couldn’t pay and spent nights on free clinics in neighborhoods other doctors wouldn’t visit.

In San Francisco, where William Chin stood at rallies in the 1950s and 60s and said, more than once, “I fought for this country alongside men who thought I didn’t belong. I will fight now for people being told the same thing.”

In New York, where an accountant named David Rosenstein volunteered weekends preserving old wartime letters—German and American—for an oral history project, because he knew how easily stories could vanish into dust.

In Tennessee, where a minister named Tommy Walker stood in front of congregations and told them that the measure of a person wasn’t how they treated friends, but how they treated enemies when the enemy couldn’t fight back.

And in Germany, in small kitchens and rebuilt hospitals and crowded classrooms, where former prisoners of war told their children about “the five Americans” who had not done what the rumors promised.

Women like Anna, who became a nurse in a Hamburg hospital and insisted that every patient—Russian, American, German—receive the same care.

Women like Greta, who went on to teach civics and snuck in stories about Geneva and Fort Douglas when the curriculum focused mainly on dates and political speeches.

Women like Magdalena, who traveled to Utah in 1980 as an old woman to stand in a former camp turned museum and say to a crowd, “When your own side has treated you as expendable, the kindness of an enemy becomes a kind of salvation.”

She wasn’t speaking in theory. She was speaking from the day a rifle barrel didn’t point at her chest, but a hand extended a canteen instead.

The Quiet Power of a Choice

Historians love big patterns: economic data, battle plans, diplomatic treaties.

When they later studied prisoner-of-war treatment in World War II, some noticed a pattern under the surface. Where PS were treated strictly but humanely—fed, sheltered, not abused—postwar outcomes were better. Former prisoners were more likely to reintegrate peacefully. More likely to accept new political realities. More likely to become people who said, “Yes, we lost—and yes, they were right to treat us as humans anyway.”

In short, humane treatment didn’t just look good in hindsight.

It worked.

Captain Morrison and his men did not have that data.

They weren’t thinking about long-term reconciliation, geopolitical stability, or the future of German democracy. They were thinking about one ruined schoolhouse full of women who had expected to die that morning.

They could have been indifferent and still technically correct.

They chose to be more than correct.

They chose to be decent.

That decision did not change the outcome of the war. The Reich would have fallen whether those five men had shown mercy or not. But it changed the meaning of the victory for everyone in that room.

It kept the winners from becoming what they hated.

It gave the losers a reason to believe that not all power meant brutality.

It turned a line in the Geneva Convention from words on a page into experience etched into memory.

And memory travels.

From diary pages into family stories, from family stories into community myths, from myths into the quieter currents of how nations see each other.

That’s how five ordinary soldiers—Morrison, Hutchkins, Chin, Rosenstein, and Walker—ended up influencing things far beyond what they could see. Not through heroics on a hilltop, but through the simple decision to treat 177 terrified women as what they were: people who had done their jobs in a bad system and now needed someone else’s system to be better.

We talk a lot about how wars are won.

We talk less about how they are ended.

The story of those five men and those 177 women is, at its core, a story about endings. About choosing what kind of people you want to be after you’ve already proved you can win by force.

In 2001, when six of those women returned to the United States—now grandmothers, frail and careful in their movements—they stood in a museum near the old Fort Douglas site and looked at four surviving men in late old age.

They hugged.

They cried.

They told their children, “This is the man who made it possible for me to be here with you.”

And one of them said, with a voice that still remembered that March morning in 1945:

“When you have been treated as less than human by your own side, the kindness of an enemy becomes a kind of salvation.”

In that sentence lies the whole point.

War is full of things no one should have to see.

But it’s also full of tiny scenes like that field hospital in Ammerbach, where someone with power looks at someone without it and realizes: I still have a choice.

That choice—to obey the bare minimum or to lean into the spirit behind the law—that’s where the world changes. Not always in big ways. But in ways that matter to the people whose lives hang in the balance.

And if enough of those small choices accumulate, across enough camps and checkpoints and ruined schoolhouses, they become something else entirely.

They become the kind of victory that doesn’t end when the guns fall silent.

The end.

News

(CH1) Admirals Called Her Chalk Trick “STUPID” – Then It Saved 48,000 Lives

At 6:43 on a raw March morning in 1943, a nineteen-year-old woman stood in a cold Liverpool basement and looked…

(CH1) How One Girl’s “SILLY” Chalk Trick Made German U-Boats Sink 3 Times Faster

At 6:43 on a cold Liverpool morning in March 1943, a nineteen-year-old woman stood in the middle of a painted…

(CH1) How One 14-Year-Old Girl’s “Crazy” Bicycle Trick Killed Nazi Officers

In the history of warfare, death usually wears a uniform. It arrives with the thunder of artillery, the scream of…

(CH1) How One US Woman’s “Shopping Trips” Saved 7,000 Allied Pilots from Nazi Prisons

March 2nd, 1943. Marseille. The coded telegram was short, cold, and devastating. “Pat has fallen.” Four hundred kilometers away, in…

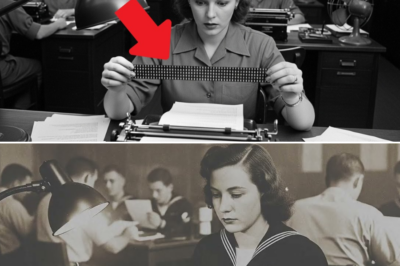

(CH1) How One American Woman’s Torn Typewriter Ribbon Saved 3,000 Lives and Sank 4 Japanese Carriers in 5 Hours

At 4:17 a.m. on May 25th, 1942, the ocean was still dark outside Honolulu, but inside the Fleet Radio Unit…

(CH1) How One Female Sniper’s “CRAZY” Trick Took Down 309 Germans in Just 11 Months

5:47 a.m. – August 8th, 1941. Belaya Tserkov, Ukraine. Twenty-four-year-old history student Lyudmila Pavlichenko crouched behind a pile of shattered…

End of content

No more pages to load