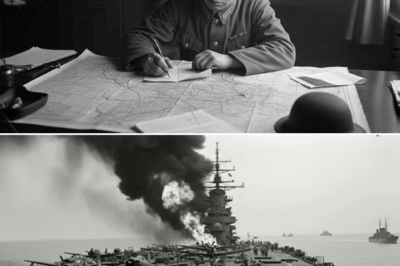

On the morning of May 24th, 1941, the North Atlantic was a steel-gray sheet under low, heavy clouds. On its surface, two great warships were trading blows—one, the pride of the Royal Navy; the other, Hitler’s newest and most terrifying weapon.

HMS Hood had been the symbol of British sea power for two decades. Long, sleek, beautiful in its way, it had toured the world as a floating declaration of empire. Its crew of 1,418 men were among the finest sailors the Royal Navy could offer.

Facing her was the German battleship Bismarck, 50,000 tons of armor and guns. She was new, her paint hardly weathered, her crew of over 2,200 brimming with confidence. Hitler had wanted a ship that would make the Royal Navy look obsolete; the result was a floating fortress with 13-inch-thick armor and eight 15-inch guns capable of killing from more than twenty miles away.

In the cold dawn, Hood and the newly commissioned battleship Prince of Wales had found Bismarck and her escort, the heavy cruiser Prinz Eugen, in the Denmark Strait. The British ships turned to attack, their main batteries opening fire across the churning water.

The crews on Hood and Bismarck watched towering plumes erupt where shells missed, counting the seconds between salvos. On the German battleship, gunnery officers calmly adjusted their aim, reading the splashes, computing corrections. On their third salvo, the German shells walked in.

One shell found its way into a vulnerable spot in Hood’s armor.

For an instant, there was nothing. Then a blinding flash ripped through the British ship, followed by a roar that seemed to split the sky. A column of flame shot up from Hood’s midsection. Her aft magazines had detonated. The ship, the pride of the Royal Navy, broke in two.

In less than three minutes, Hood was gone.

Of her crew, only three men were pulled from the freezing Atlantic.

On Bismarck, some of the sailors cheered. Others simply stood stunned. They had just killed the most famous warship in the world with almost frightening ease. Yet in the gunnery plot, where the German officers tracked hits and trajectories, a small notation was made. A British shell had struck Bismarck as well, piercing her bow and ripping open one of her fuel tanks. Oil was leaking into the sea.

It was an ominous wound in an otherwise triumphant moment.

In Berlin, the news of Hood’s destruction ran like electricity through the Nazi leadership. Hitler had his symbol. British morale took a blow. Churchill, reading the report, felt the weight of it settle onto his shoulders. A single German battleship was now loose in the Atlantic, and Britain’s survival depended on the convoys that crossed that ocean every day.

“Bismarck is out,” read the simple signal that reached him.

He responded with an order that was less command than ultimatum: “Sink the Bismarck.”

The German plan, at least on paper, was straightforward. Bismarck and Prinz Eugen would break into the Atlantic, find convoys laden with food, fuel, and equipment, and tear them apart. If they succeeded, Britain—already rationing everything from bread to petrol—could be starved out of the war.

But Kapitän Ernst Lindemann, Bismarck’s captain, understood the unspoken limit of his ship’s power. Bismarck could outgun any single British battleship, outrun most of them, and shrug off punishment that would cripple older ships. What Germany did not have was a fleet to match the Royal Navy. There would be no line of battle, no supporting squadrons. Bismarck was magnificent—but alone. If she was ever trapped by superior numbers, she would die.

After the battle with Hood, Lindemann and Fleet Commander Admiral Günther Lütjens made a crucial decision. Rather than continue the original mission alongside Prinz Eugen, they separated. Prinz Eugen would go hunting convoys alone. Bismarck—damaged, bleeding oil and burning through precious fuel—would head for the safety of occupied France and a repair dock.

British cruisers shadowed her at a distance, keeping contact by radar. For a time, it seemed the net was holding. Then, during the night of May 24–25, Bismarck turned sharply toward her pursuers and vanished into a rain squall. The British radar screens went suddenly blank.

The most dangerous ship in the world had disappeared into more than three million square miles of Atlantic.

In London, in the Admiralty’s underground war rooms, panic flickered under the professional calm. Was Bismarck heading back to Norway? Had she already turned south and begun slaughtering convoys? Every hour she remained unfound was a chasm into which shipping losses could fall.

What broke the silence was not a brilliant maneuver by the hunters, but a fatal mistake by the hunted.

Admiral Lütjens believed that Bismarck was still being trailed. Convinced the British were listening to his orders anyway, he sent a long radio message to Berlin, thirty minutes of transmission detailing intentions and course.

He did not know that the British had lost contact hours before.

Radio direction-finding stations along Britain’s coast and in Iceland listened. The transmission was so long and strong that it might as well have been a flare in the night. Operators triangulated its source and got a bearing: Bismarck was well on her way south, aiming for the French port of Saint-Nazaire.

When the plot was laid out on the chart, a new horror emerged. The British battleships still far to the north and west could not possibly intercept her before she reached Luftwaffe protection. The only ship in range was the aging aircraft carrier Ark Royal, sailing with Force H out of Gibraltar.

Ark Royal’s air group did not consist of sleek, modern monoplanes. Its primary torpedo bomber was the Fairey Swordfish: an anachronistic, canvas-covered biplane that looked as if it had wandered into the wrong war. It flew barely faster than 90 miles per hour. Its pilots sat in open cockpits, exposed to wind, spray, and every bit of flak the enemy could throw at them.

And yet, there was no other option.

On the evening of May 26th, fifteen Swordfish biplanes took off into rough weather. Somewhere in the murk ahead of them lay a battleship bristling with anti-aircraft guns, a ship that had already sent one British legend to the bottom.

As the Swordfish descended through clouds and rain, Bismarck’s lookouts spotted them. Sirens wailed. The great ship’s batteries swung up, and guns of all calibers opened fire. Tracer fire stitched the sky.

But something unexpected happened. The Swordfish were so slow and so low that the sophisticated fire control systems on Bismarck’s flak guns—designed to track and predict the movements of much faster, higher-flying targets—struggled to lock onto them properly. The biplanes came in through a storm of steel, buffeted but intact.

Fourteen torpedoes were dropped from wobbly wings.

Fourteen torpedoes missed, detonated harmlessly, or struck armor with little effect.

One did not.

It hit Bismarck near the stern, in the area of the twin rudders.

The explosion jammed both rudders hard over at 12 degrees to port.

Inside Bismarck’s hull, engineering crews fought furiously to free them. Divers went down into flooded compartments. Tools clanged. Men shouted. Water seeped through torn plates.

Nothing worked.

The most advanced battleship in the world, capable of 30 knots, could now only steam in wide, helpless circles. Every attempt to steer with propellers alone still curved her path. She was no longer a predator. She was prey.

And, cruelly, her arcs through the Atlantic were now carrying her back toward the oncoming British fleet.

Captain Lindemann understood what that meant. There would be no reaching France. No Luftwaffe umbrella. No clever slipping away this time. They would be found and forced into a battle they could not win.

He addressed the crew.

“We will fight to the last shell,” he signaled. “Long live the Führer.”

At dawn on May 27th, the British battleships Rodney and King George V caught up with Bismarck. Accompanying them were cruisers that had helped locate and harry the German ship through the night.

The engagement that followed was not an evenly matched duel like the earlier fight with Hood. It was more like an execution.

From relatively close range, the British ships opened fire with everything they had. Shell after shell smashed into Bismarck’s superstructure, blowing away rangefinders, wrecking turrets, blasting the bridge apart. Plumes of water and flame rose from each impact. The German ship’s return fire grew more sporadic, then fell silent as guns were knocked out or power lost.

For nearly two hours, British shells tore the upper works of Bismarck into twisted wreckage. Masts toppled. Fires raged. Men died in terrible numbers.

Yet, despite the devastation above the waterline, the battleship refused to sink. Her armored hull, designed to withstand enormous punishment, still kept the sea at bay.

Finally, German damage control teams, recognizing the hopelessness, opened scuttling charges and sea valves deep inside the ship to ensure she would not be captured. Torpedoes from British ships struck her sides.

Shortly after 10:30 in the morning, Bismarck rolled heavily, capsized, and slid beneath the waves, stern last, vanishing into the cold Atlantic three miles down.

She had been at sea for eight days.

Of the more than 2,200 men who had set out aboard the invincible battleship, only 114 were hauled alive from the oil-slicked water.

The Bismarck became a legend for many reasons. For some, she was a symbol of terrifying power—a single ship that, for a brief moment, frightened an empire. For others, her story was a cautionary tale about investing too much in a single weapon.

She had proved that a battleship could still kill with shocking speed in the age of air power and submarines. She had also proved a harder truth: that no weapon, however advanced, is invincible if it fights alone.

Bismarck was, in many ways, the perfect battleship.

She was also the wrong weapon for the war she was in.

And in the end, her only lasting dominion was on the ocean floor, a vast hull surrounded by silence—a monument to eight days when she ruled the Atlantic, and to the countless men on both sides who learned, at terrible cost, that even monsters of steel can bleed.

The end.

News

The Brutal Coincidence that Cost Germany 25,000 Soldiers

The Trap at Mons September 1944 Southern Belgium Two tides were flowing across the fields. One was ragged, gray, and…

The Tank American Crews Asked For – Why the M26 Pershing Missed WWII’s Big Battles

July 27, 1944 Near Saint-Lô, Normandy The Panther’s gun thundered. Inside the turret, the shockwave rolled through steel, through bone….

(CH1) The Secret Sherman: Why German Troops Couldn’t Destroy US M4 Tanks | Wet Stowage Explained

July 27, 1944Near Saint-Lô, Normandy The Panther’s gun thundered. Inside the turret, the shockwave rolled through steel, through bone. The…

(CH1) German Child Soldiers Braced for Execution — Americans Brought Them Coca-Cola Instead

Story title: The Coca-Cola in the Snow The last days of the war tasted like dirt and metal. Thirteen-year-old Oskar…

Former Goebbels Officer Expects Torture in US Prison Camp—What He Gets Instead Breaks Him Completely

Story title: From Lies to Headlines 1. Surrender with a Satchel of Lies May 8, 1945 Southern Bavaria The last…

(CH1) Japanese Admirals Thought The US Navy Was Crippled — Until 6 Months Later At Midway.

TOKYO — DECEMBER 8, 1941 The air in the Imperial Japanese Navy headquarters is thick with cigarette smoke and triumph….

End of content

No more pages to load