Story title: The Silver That Split the Atom

1. “We Need 6,000 Tons”

August 3, 1942

Washington, D.C. – U.S. Treasury Building

Lieutenant Colonel Kenneth Nichols felt sweat bead under his uniform collar as he walked past marble columns and into the cool, echoing corridors of the Treasury.

He was an engineer. A practical man. He knew the weight of steel, the stress limits of bridges, how many truckloads it took to move a battalion’s worth of supplies.

He did not normally think in precious metals.

The secretary ushered him into the office of Under Secretary of the Treasury Daniel W. Bell.

Bell was a money man. His world was numbers, ledgers, reserves—gold bars in vaults, silver in deep storage at West Point, all of it representing the wealth of a nation at war.

Nichols sat.

Bell didn’t waste time.

“What can the Treasury do for the War Department, Colonel?” he asked.

Nichols took a breath.

“I need to borrow metal,” he said. “A lot of metal.”

“For coins?” Bell asked. “Shell casings?”

“I can’t tell you exactly,” Nichols said. “Project is classified. Highest priority. But we need high-conductivity metal for large electromagnetic coils. Copper, preferably.”

“How much?” Bell asked.

Nichols swallowed.

“Five thousand short tons,” he said. “Perhaps as much as six.”

Bell’s pen stopped.

There was a long moment of silence.

“How many troy ounces is that?” he asked.

Nichols blinked.

“Troy… ounces?” he repeated.

“Yes,” Bell said, a flash of irritation in his voice. “We account for bullion in troy ounces. How many?”

Nichols spread his hands.

“I don’t know how many troy ounces,” he said, patience thinning. “But I do know I need six thousand tons. That’s a definite quantity. What difference does it make how we express it?”

Bell leaned forward, affronted in the way only a man whose entire life was denominated in precise units could be.

“Young man,” he said, “you may think of silver in tons. The Treasury will always think of it in troy ounces.”

There it was.

He’d said “silver.”

Nichols hadn’t.

Not yet.

Because the impossible conclusion was now on the table: if copper wasn’t available, they’d have to use something else.

Silver.

The metal in coins.

The metal in the people’s reserves.

The metal in the vaults at West Point.

And he was asking to melt it down and turn it into giant magnet windings for a machine he couldn’t even describe.

2. The Problem: Three Neutrons

To understand how insane that sounded, you have to understand the problem the Manhattan Project faced in 1942.

Scientists knew that uranium-235 was the key to a bomb.

Hit a U-235 nucleus with a neutron and it splits—fission—releasing a tremendous amount of energy and more neutrons. Those neutrons can hit other U-235 nuclei, and the process cascades into a chain reaction.

But natural uranium is almost all the wrong kind of uranium.

Out of every thousand atoms, a little over seven are uranium-235.

The other nine hundred ninety-three are uranium-238.

Chemically, they’re identical.

Same number of protons.

Same electrons.

Same chemical behavior.

The only difference is three neutrons in the nucleus.

U-238 has 146.

U-235 has 143.

That tiny difference in mass was the only handle engineers had to grab.

To build a weapon, they needed uranium that was over 90% U-235.

They had to separate isotopes that refused to cooperate.

Multiple methods were on the table:

Gaseous diffusion – forcing uranium hexafluoride gas through porous barriers so the slightly lighter U-235 molecules moved a bit faster.

Thermal diffusion – using temperature gradients to drive slight separations.

Centrifuges – spinning gas at high speed to push the heavier isotope outward.

All promised something.

All were technical nightmares at scale.

Then Ernest Lawrence, a physicist at Berkeley and inventor of the cyclotron, suggested something that sounded like madness.

Turn the whole process into a giant physics experiment.

Use magnetism.

3. Lawrence’s Idea: Big Physics, Bigger Machines

Lawrence’s lab had built cyclotrons—circular machines that accelerated charged particles in spirals using magnetic fields. He knew that if you pass ions through a magnetic field, their paths curve.

The heavier they are, the less they curve.

The lighter, the more.

What if, he thought, you ionize uranium atoms, send them through a strong magnetic field, and let the slightly lighter U-235 atoms veer off just a bit more than the heavier U-238?

Catch them in different collectors.

You’ve separated isotopes.

It was essentially a mass spectrometer blown up to industrial size.

In late 1941, Lawrence’s team took a 37-inch cyclotron and converted it into a prototype separation device.

They gave it a name: calutron—from “California University cyclotron.”

On December 2, 1941—five days before Pearl Harbor—the first calutron ran a test.

A faint beam of uranium ions struck the collector.

The principle worked.

By January 1942, they were producing micrograms of partially enriched uranium.

Not much.

But more than anyone had ever managed.

Turning micrograms into the kilograms needed for a bomb, however, meant building calutrons by the hundreds.

And that meant magnets.

Enormous magnets.

Each magnet would be the size of a room. The coils would carry thousands of amps. They needed to be wound with miles of conductive metal.

Copper was the obvious choice.

Copper was also on everyone else’s wish list.

Ships. Planes. Tanks. Radios. Ammunition. Every branch of the service and every war industry was screaming for it.

The Manhattan Project was important.

It was not, in mid-1942, the only thing going on.

So Nichols and his boss, Colonel James Marshall, faced a brutal reality: they couldn’t get enough copper.

They needed another conductor.

Silver is the best electrical conductor there is—better than copper by about 10%.

Eleven pounds of silver can do what ten pounds of copper can.

The War Department did the math.

If they replaced 5,000 tons of copper, they’d need roughly 5,500 tons of silver.

There was only one place to get that much in a hurry.

The Treasury’s bullion vaults.

Hence Nichols in Daniel Bell’s office, explaining that he wanted to melt down part of the nation’s silver holdings for an unspecified machine in Tennessee.

4. Borrowing the People’s Silver

Bell agreed.

Eventually.

Under strict conditions.

The silver would be loaned, not given.

It would be measured out in troy ounces—1,000-ounce bars, each about 31 kilograms—and shipped under heavy guard from West Point to industrial plants.

Every ounce would be accounted for.

Nichols would file monthly reports.

When the war ended, the silver would be returned.

Melted back into bars.

Restacked in the vaults.

Six thousand tons turned out to be an underestimate.

As designs expanded and more calutrons were ordered, the requirement grew.

In the end, the Treasury lent 14,700 short tons of silver.

That’s about 13,300 metric tons.

Roughly 430 million troy ounces.

In 1942 dollars, about $300 million worth.

In today’s money, roughly six billion.

All to build magnets.

The bars left West Point on trains, guarded like any king’s ransom.

At the Defense Plant Corporation facility in Carteret, New Jersey, the gleaming ingots were melted and cast into cylindrical billets.

Those billets went to Phelps Dodge in Bayway, where they were extruded under immense pressure into long strips—0.625 inches thick, three inches wide, forty feet long.

Two hundred fifty-eight carloads of silver strips rolled under guard to Allis-Chalmers in Milwaukee.

There, engineers wound the strips onto huge magnetic coil forms—layer upon layer of silver ribbon—then sealed them inside welded steel housings.

By the time the coils reached Oak Ridge, Tennessee—often on unguarded flatcars—they didn’t look like silver at all.

They were just big, anonymous chunks of industrial equipment.

Only paperwork and a handful of people knew what gleamed inside.

5. Y-12: Racetracks of Uranium

Bear Creek Valley, near Oak Ridge, became home to the electromagnetic separation plant.

Code name: Y-12.

From the air, the main process buildings looked like long rectangles. Inside, the calutrons were arranged in giant ovals dubbed “racetracks”.

Each racetrack consisted of U-shaped magnets arranged in a loop. Between their poles sat vacuum tanks—14-ton steel chambers—where the separation happened.

Here’s how a calutron worked, stripped to essentials:

-

Feed uranium tetrachloride into an ion source, heat it, and strip electrons to create positively charged uranium ions.

Accelerate those ions through an electric field so they form a beam inside the vacuum chamber.

Apply a strong magnetic field perpendicular to the beam. The ions curve as they move.

Because U-235 ions are slightly lighter, their path curves more than U-238.

Place catcher plates at positions where U-235 and U-238 beams diverge.

Let the ions deposit as metal on those plates. Later, chemically extract and process.

It sounds clean.

In reality, it was messy.

Vacuum tanks warped under magnetic forces and thermal expansion, drifting out of alignment.

Moisture crept into coils, causing short circuits and corrosion.

Inside the tanks, “crud” accumulated—condensed vapors, dust, flakes of metal—clogging slits and scattering beams.

Ion beams heated components over long runs, warping collectors.

Engineers added braces, upgraded pumps, redesigned cooling.

Every problem solved revealed the next.

And through it all, the silver had to be protected.

When holes were drilled in silver parts, workers laid paper underneath to catch every shaving.

At the end of shift, the paper was burned, the ashes processed to recover particles.

Later, when equipment was dismantled, even floorboards under machines were pulled up and burned for recovery.

Nichols lived with a second set of numbers in his head: not just grams of U-235 produced, but troy ounces of silver accounted for.

6. The Calutron Girls

The science and engineering were complex.

Operating the machines, however, was a different kind of challenge.

The military hired Tennessee Eastman, a subsidiary of Eastman Kodak, to run Y-12.

Tennessee Eastman hired thousands of workers from the surrounding area.

Many were young women from farms and small towns—high school graduates, some barely out of school.

They became known as the “calutron girls.”

They trained not in physics, but in procedures.

This dial: keep the needle in this band.

That meter: if it drifts, turn this knob a hair to the left.

That gauge: if it spikes, alert your supervisor.

For security, they weren’t told what the machines did.

They didn’t know what uranium was or what mass separation meant.

They were told only that the work was vital.

“Like soldiers,” Nichols later said, “they were trained not to reason why.”

When the first alpha racetracks (the initial stage of enrichment) and beta racetracks (the polishing stage) came online in 1944, the Berkeley physicists who’d designed them stayed on for a while to debug.

They ran the calutrons themselves at first.

Then, as procedures stabilized, operations were turned over to Tennessee Eastman and the young women in their white uniforms at the control panels.

Nichols, ever the engineer, compared output.

He noticed something odd.

When the scientists ran the machines, production lagged.

When the local operators ran them, production improved.

He showed Ernest Lawrence the data.

Lawrence, proud of his team, doubted it.

They staged a test.

Berkeley PhDs on one racetrack.

Calutron girls on another.

Same feed material.

Same conditions.

After a fixed period, they compared.

The women won.

The reason was simple.

Physicists couldn’t help investigating anomalies.

If a dial fluttered, they wanted to know why. They’d tweak, test, hypothesize.

The operators did exactly what they were trained to do.

If a needle drifted, they turned the knob and moved on.

The machines stayed in their sweet spot more consistently.

Understanding mattered for design.

Execution mattered for output.

Both were essential.

7. Little Boy and the Bill Comes Due

By mid-1944, Y-12’s output began feeding into weapons plans.

It wasn’t the only game in town—gaseous diffusion at the nearby K-25 plant and work at Hanford on plutonium were also crucial—but Y-12 produced essentially all of the U-235 that would wind up in the first uranium bomb.

By July 1945, they had enough.

About 64 kilograms of uranium, enriched to roughly 80% U-235, formed the core of the gun-type weapon code-named Little Boy.

On August 6, 1945, that weapon exploded over Hiroshima.

The blinding physics realized, at a human cost that is still hard to comprehend.

Three days later, a plutonium bomb—Fat Man, built from Hanford’s output—destroyed much of Nagasaki.

Japan surrendered on August 15.

The war ended.

Y-12’s calutrons had done their job.

In the new nuclear age, however, electromagnetic separation was too energy-hungry to be the long-term solution for large-scale enrichment. Gaseous diffusion proved more efficient at industrial capacities, then later gas centrifuges.

The calutrons were phased out.

The magnets fell silent.

The silver had to go home.

8. Paying Back the Silver

Dismantling Y-12’s electromagnetic machines was an exercise in industrial archaeology and forensic accounting.

Coils were unwound.

Casings opened.

Silver strips coiled back onto spools, weighed, and tallied.

Equipment was wiped down.

Burned.

Leached.

Every process aimed at retrieving atoms of silver that had crept into places no one had intended.

At the end, out of roughly 430 million troy ounces loaned, about 155,645 troy ounces were unrecoverable—lost to chemical reactions, embedded in slag, vaporized into places impossible to reclaim.

That was less than 0.04%.

Well within what the Treasury considered acceptable loss under the circumstances.

The bars went back to West Point.

The accounting balanced.

In a sense, the American people got their silver back.

They could never get back the innocence that had existed before anyone knew what U-235 could do to a city.

By 1970, the last pieces of silver still in use in electrical equipment at Y-12 were replaced with copper and returned.

The loan, on paper, was fully repaid.

9. Execution and Understanding

The calutron story is easy to file mentally next to other quirky wartime anecdotes—like the time the Navy tested magnetic torpedoes on dummy ships and sank one by accident.

But it’s more than a footnote.

It shows what desperate engineering looks like when the clock is ticking and the stakes are existential.

Take a lab technique.

Scale it up by factors of a million.

Discover every failure mode the hard way.

Patch.

Repeat.

It also highlights something about how complex systems actually work.

The brilliance of Lawrence and his colleagues was indispensable.

Without their understanding of electromagnetic separation, without their insistence that it could work if you just built it big enough, Y-12 would never have existed.

But without thousands of anonymous operators sitting at panels, eyes on dials, hands on knobs, the calutrons would have been museum pieces.

The Calutron girls didn’t know about neutrons or isotopes.

They knew that if Dial A drifted, you nudged Knob B.

They knew that if the needle flickered out of the green, you called a supervisor.

They knew that procedures, followed carefully, could move mountains of atoms.

Understanding built the machine.

Execution made it matter.

10. Silver, Needles, and Responsibility

There’s something almost mythic about the image: bars of silver, stamped with purity, pulled from vaults to become windings in magnets that would bend uranium atoms on their way to a bomb.

Nichols’ monthly reports to the Treasury, listing troy ounces consumed and returned, read like the bookkeeping of some industrial alchemist.

We took this amount from the realm of money.

We turned it into something that changed the world.

We turned most of it back.

The Calutron girls learned, years later, what their needles had really kept in the green.

Some were proud.

They’d helped end a war.

Some were horrified.

They’d helped unleash the bomb on Hiroshima without knowing it.

Most lived with the ambiguity.

They did their jobs, well, at a moment when the outcome of the war still felt uncertain.

Nichols himself, reflecting in his memoirs, recalled Bell’s line about troy ounces and thought it captured something essential.

The Treasury saw silver as value to be guarded.

He had seen it as conductivity to be used.

Both were right, in their own frames.

It took a war, a physicist’s audacity, an engineer’s stubbornness, a banker’s caution, and thousands of workers’ steady hands to turn those frames into one story.

A story where intangible things—trust in science, belief in victory, fear of the enemy getting there first—were converted into very tangible things: racetracks of magnets humming in a Tennessee valley, beams of uranium bending under invisible forces, a mushroom cloud rising over a city.

In the end, the silver went back into the vaults.

The calutrons went quiet.

Y-12 found new roles in the nuclear weapons complex.

The world moved on to new technologies, new crises, new problems to solve.

But the questions the Calutron story raises linger:

How far are we willing to bend our systems—economic, industrial, ethical—to solve a problem we believe is existential?

How do we weigh understanding versus execution?

Who gets remembered?

Ernest Lawrence has a national lab named after him.

Kenneth Nichols appears in histories as the officer who “borrowed” the silver.

Daniel Bell remains the man who insisted on troy ounces.

The Calutron girls, the machinists, the coil winders, the train crews, the nameless clerks who reconciled silver ledgers—all of them remain mostly in shadows.

Yet without them, the magnets wouldn’t have worked, the beams wouldn’t have bent, and the plutonium and uranium cores in the first bombs would have remained, stubbornly, mixed isotopes in metal ingots.

In a world still wrestling with the legacy of those bombs, it’s worth remembering that history isn’t just written in treaties and test sites.

Sometimes it’s written in the quiet confidence that you can borrow a nation’s silver—

And in the steady hand of a young woman in Tennessee keeping a needle in the green zone.

News

The Brutal Coincidence that Cost Germany 25,000 Soldiers

The Trap at Mons September 1944 Southern Belgium Two tides were flowing across the fields. One was ragged, gray, and…

The Tank American Crews Asked For – Why the M26 Pershing Missed WWII’s Big Battles

July 27, 1944 Near Saint-Lô, Normandy The Panther’s gun thundered. Inside the turret, the shockwave rolled through steel, through bone….

(CH1) The Secret Sherman: Why German Troops Couldn’t Destroy US M4 Tanks | Wet Stowage Explained

July 27, 1944Near Saint-Lô, Normandy The Panther’s gun thundered. Inside the turret, the shockwave rolled through steel, through bone. The…

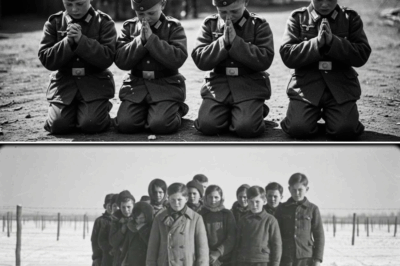

(CH1) German Child Soldiers Braced for Execution — Americans Brought Them Coca-Cola Instead

Story title: The Coca-Cola in the Snow The last days of the war tasted like dirt and metal. Thirteen-year-old Oskar…

Former Goebbels Officer Expects Torture in US Prison Camp—What He Gets Instead Breaks Him Completely

Story title: From Lies to Headlines 1. Surrender with a Satchel of Lies May 8, 1945 Southern Bavaria The last…

(CH1) Japanese Admirals Thought The US Navy Was Crippled — Until 6 Months Later At Midway.

TOKYO — DECEMBER 8, 1941 The air in the Imperial Japanese Navy headquarters is thick with cigarette smoke and triumph….

End of content

No more pages to load