In the early years of the war, most men in German uniform thought of the United States the way you think of a distant storm on the horizon. Impressive to look at, perhaps, but too far away to ruin your house.

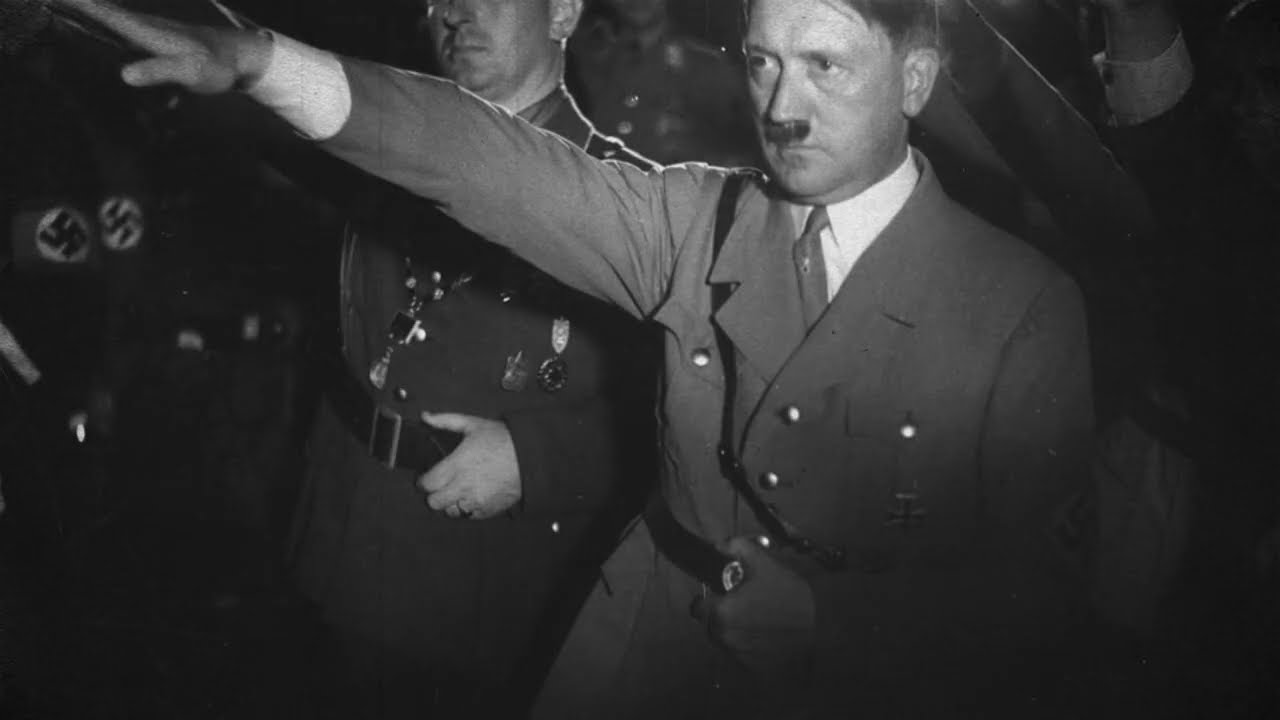

In Berlin, they talked about America with an easy contempt. Hitler called it a “country of businessmen,” a place where people argued instead of obeyed, where politics was messy and the army soft. Its diversity, he said, made it weak. Its democracy made it indecisive. In private, he was even blunter: “They cannot wage a real war.”

On maps in German headquarters, the United States was a block of color across an ocean. Imposing, yes, but slow and clumsy, too divided and too distant to seriously affect the battles being fought in Russia, North Africa, and over Europe’s skies.

For a time, it seemed he might be right.

Then 1942 happened.

Even before America was formally at war, something had begun to stir behind its borders. Factories that had once turned out cars learned to build tanks. Assembly lines that used to spit out refrigerators were retooled to produce aircraft engines. Shipyards that had launched a few ships a year began floating Liberty ships off their slips in weeks—sometimes in days. Entire industries reinvented themselves with a speed no one in Berlin could quite believe, and reports that tried to describe it were quietly edited before they landed on Hitler’s desk. The Führer wanted confirmation of his world view, and too many people obliged.

In the North Atlantic, U-boat commanders initially reveled in success. They posed in leather coats, claimed they held Britain’s throat in their periscopes, and bragged that the island would starve before American help could arrive. But slowly, almost imperceptibly at first, the arithmetic changed. For every freighter they sent to the bottom, two more seemed to appear on the horizon. Convoys they mauled one month were reconstituted the next with modern, sturdier ships. The sinking totals stayed high, but the effect they were supposed to produce—choking Britain—never came. “It is like bailing out the ocean with a bucket,” one U-boat officer sighed after the war.

When American soldiers appeared in Tunisia and Morocco, their first impressions confirmed German prejudice. The GIs were green, awkward in the field, prone to mistakes. At Kasserine Pass they broke and ran under blows the Africa Corps thought routine. “They are strong, but clumsy,” Rommel reportedly judged. “They learn slowly.”

The problem, from the German point of view, was that the Americans did learn.

By mid-1943, the same units that had fumbled in North Africa were fighting like veterans in Sicily and Italy. Their equipment was not always elegant, but it was reliable and arriving in staggering quantities. Tanks that had seemed easy prey at first came back with thicker armor, better guns, refined designs. What Germany fixed with scarcity and ingenuity, America drowned under waves of steel.

The true shock, though, did not come on the ground, but from the sky.

Germany had taken pride in its air defenses. It built flak towers like modern castles and believed its factories and rail yards could endure whatever the Allies threw at them. British bombers, flying at night, had already shown that cities could burn. But the Germans, for all the grief, could still tell themselves that their industrial heartland was essentially intact, its blows painful but survivable.

Then the Americans began their daylight raids.

They came in tight formations, in numbers that made the horizon seem metallic. B-17s and B-24s droned over in streams, blotting out patches of sky. Unlike the British, they tried to hit factories, refineries, and rail junctions with precision. The price was high. The early missions to places like Schweinfurt and Regensburg cost dozens of bombers at a time. Yet they kept coming, and their accuracy improved.

Synthetic fuel plants—Germany’s lifeline as its oil sources dwindled—were bombed again and again. Each time they were patched up, another raid followed, undoing months of repair in hours. Rail yards were cratered, locomotives turned into twisted metal, bridges blown from their supports. German officers who watched the sky began to say it felt like thunder that never stopped.

Inside his headquarters, Hitler raged. He blamed the Luftwaffe for failing, his ministers for incompetence, saboteurs for imagined treachery. He refused to accept that the scale of American production and persistence had outstripped Germany’s ability to respond. But in the Wehrmacht’s staff rooms and air defense centers, a quieter understanding settled in. This wasn’t a symbolic contribution from a distant ally. This was one of the main engines of the war, and it was running hotter every month.

D-Day—the 6th of June, 1944—turned that understanding from murmur into shock.

German commanders in Normandy awoke that morning to the sound of naval guns so heavy they seemed to punch the sea itself. Off the coast, ships of every size stretched almost to the horizon. Landing craft spilled forth men and vehicles in numbers that defied belief. This wasn’t a raid. It wasn’t a limited landing. It was an army being poured onto French beaches with orchestral coordination.

It wasn’t just the sheer volume of ships and men that stunned German observers. It was the way they moved together. Engineers came ashore almost with the first waves, clearing obstacles and laying roads with practiced speed. Medics had casualty stations functioning within hours. Tanks rolled off landing craft as if they had rehearsed it all a hundred times. Everything that an army needed to fight—food, ammunition, fuel, spare parts—flowed across improvised docks, onto trucks, and then inland.

“This is not possible,” one German officer radioed desperately as he watched the landings. “No other nation can do this.”

He was right.

By the time the Allies broke out of the Normandy bocage in late July and began racing across France, the rhythm of the war had changed entirely. American-led forces moved like a tide, bridging rivers, repairing roads, and redeploying divisions with a speed that German logistics simply couldn’t match. Behind the front, an intricate web of supply depots, fuel dumps, maintenance units, and transport columns kept the spearheads fed and fueled. German intelligence officers looking at aerial photographs whispered among themselves about “a conveyor belt of war.”

The Wehrmacht tried one last time to turn the tide in December 1944.

The Ardennes Offensive—what the Allies would call the Battle of the Bulge—was meant to be a brutal surprise that would shatter the Allied lines, capture Antwerp, and throw the Western Front into disarray. The attack, launched under cover of bad weather, hit American units in Belgium and Luxembourg hard. For a week, the front buckled. Town names like Bastogne became desperate fighting words.

Hitler had counted on the Americans being soft, unable to withstand shock. His generals hoped that, with the skies closed to Allied aircraft by snow and fog, they could bleed their way forward.

What they saw instead was resilience.

American units caught in the initial blows held on, even when surrounded. Other divisions were shifted from quiet sectors and from as far away as the Saar in a matter of days, filling holes, reinforcing threatened points. When the weather finally cleared, Allied aircraft roared back into action, pounding German columns that had burned fuel they could not replace. The offensive, meant to break the Allies, instead broke the last reserves of German strength in the west.

From that point, the end was more a question of time than of outcome.

As 1945 began, American divisions rolled into Germany itself. The bombing had already broken much of the nation’s back. Now tanks and infantry advanced through shattered towns and across ruined fields. Bridges the Germans blew up were replaced with temporary Bailey bridges in a day or two. Roads chewed apart by craters were graded and made passable in hours. Supply lines reached so deep into Europe that some GIs joked they could probably get ice cream at the front if they asked.

Captured German officers, sitting in POW cages or being interrogated in requisitioned villas, talked about the Americans in language that had nothing to do with the old propaganda. They spoke of unending artillery, of skies filled with aircraft, of fresh uniforms and vehicles and a sense among American troops that they would not run out of anything except patience.

“You do not defeat them,” one said bleakly. “You endure them. And even that now is too much.”

When American units began liberating concentration camps, another kind of realization hit.

The soldiers who walked into places like Buchenwald and Dachau weren’t prepared for what they saw—the emaciated survivors, the piles of corpses, the personal belongings stripped from millions. They brought in photographers, cameramen, and investigators. They forced local German civilians to see the camps with their own eyes.

For Germany, it was a double defeat.

Militarily, they were being crushed by a force they had laughed at only a few years earlier. Morally, the nature of their regime was being exposed to the world by that same enemy. The United States not only had the capacity to break the Luftwaffe and cross the Rhine; it had the discipline to document the crimes the Nazis had tried to bury and show them to everyone.

By the spring of 1945, as American columns linked up with Soviet forces on the Elbe, the last illusions in German headquarters withered. Hitler still talked of miracle weapons, of last-minute jet fighters and rockets, of plans that might reverse everything. Around him, officers said less and nodded more. They had seen enough.

One of them, a veteran of both Russia and France, reportedly told a colleague in a rare moment of honesty, “We thought America was a giant with soft bones. We were wrong. They are a giant with steel bones.”

When German generals looked back after the war, many admitted a brutal truth. They had underestimated American industry, thinking factories didn’t fight. They had underestimated American soldiers, assuming comfort bred weakness. They had underestimated American resolve, believing democracies could not sustain total war.

By the time they understood that America could reinvent its economy, pour out ships and planes and tanks in numbers no one had encountered before, learn from every mistake, and project power across oceans with almost mechanized reliability, it was far too late to matter.

There was no single moment when Germany woke up to what America was. No single explosion, no single battle.

But the recognition came into sharp focus in those final months: in the roar of engines over ruined cities, in the steady rumble of tanks crossing the Rhine, in the realization that the nation they once mocked as soft and unfocused had turned out to be the deciding weight on the scales.

In the end, the Third Reich did not fall to some mythical invulnerable super-soldier or secret weapon. It fell, in no small part, to a country it had laughed at—one that built, moved, adapted, and endured in ways its leaders had never imagined.

News

My Family Uninvited Me From Christmas At The $8,000 Chalet I Paid For, So I Canceled It And Watched Their Perfect Holiday Dreams Collapse.

If you’d walked past our house when I was a kid, you probably would have thought we were perfect. We…

(CH1) What General Bradley Said When Patton Freed France Faster Than Anyone Thought Possible

PART I: WHEN THE DOOR FINALLY BROKE OPEN August 1944, France For eight long, punishing weeks, we had been stuck….

(CH1) What Eisenhower Said When Patton Asked: “Do You Want Me to Give It Back?”

PART I: THE PROMISE December 19th, 1944Whitehall, London The war room beneath Whitehall did not need heating. It was already…

(CH1) “That’s Not a General” — German Officers Refused to Believe the Man in the Jeep Was Patton

PART I: THE MAN THE GERMANS COULDN’T FIND March 1945. Western Germany. The interrogation room had once been a school…

(CH1) How One Factory Girl’s Idea Tripled Ammunition Output and Saved Entire WWII Offensives

PART I: SECONDS 0710 hours. July, 1943.Lake City Ordnance Plant, outside Independence, Missouri. The building shook like a living thing….

Ana Morales, his maid, was finishing up for the day, her six-year-old daughter Lucia skipping behind her in an oversized Santa hat. They were heading home.

By the time the first snowflake drifted past his window, the city below was already wearing its winter disguise. Edinburgh,…

End of content

No more pages to load