They had laughed at America long before they ever saw it.

Around smoky campfires in Russia and under low tarpaulins in Italy, German soldiers mocked the men they had never met. American troops, they said, lived on chocolate, chewing gum, and coffee. Radio broadcasts from Berlin fed them the lines: the United States was soft, its people spoiled, its soldiers dependent on luxuries. A few propaganda cartoons showed smiling GIs with candy bars and bottles of Coca-Cola, and in the trenches those images became jokes they repeated to keep warm.

“We eat black bread and cabbage soup,” they would say, “and they need steak to fight.”

Behind the bravado, the mockery was a shield. It was easier to laugh at American abundance than to face what it really meant. An army that could feed its men that well and still build tanks, planes, and ships in endless numbers might not be weak at all. It might be something else entirely.

Karl Weber, a twenty-three-year-old infantryman from the Ruhr, had told the jokes as often as anyone. He had grown up in a country where coffee was already a memory and meat had become a Sunday rumor. By late 1944, his rations consisted mostly of gray bread cut with sawdust, ersatz coffee, and watery soup that tasted faintly of turnip and metal. When American aircraft strafed their positions, he cursed them as pampered cowards. When Allied leaflets fluttered down showing well-fed prisoners of war in clean uniforms, he called them lies.

That was before the end came.

In the winter of 1944–45, German units began to collapse. In North Africa, then Italy, then France and finally in the West itself, entire formations laid down their arms. Karl was captured near Aachen after his unit, reduced to a handful of men, ran out of ammunition. A tired American machine gunner motioned him forward with the barrel of his weapon. There was no fight left in him anyway.

In the holding pens behind the lines, the jokes returned, but now they came with an edge.

“I wonder what we’ll be eating over there,” someone said as they huddled in their greatcoats. “American luxuries, eh?”

“They’ll starve us,” another answered. “Or work us to death in mines. Either way, we’ll find out what their ‘humanity’ looks like.”

Rumors thickened as they were marched to the ports. Some insisted that prisoners shipped to America were fed only scraps, treated worse than cattle. Others swore they would be put in chains and paraded through the streets. Nobody expected kindness. Very few expected normal food.

The Atlantic crossing was cramped and foul. The converted troop ship pitched and rolled. The air in the lower decks smelled of sweat, vomit, and old diesel. When the smells from the galley drifted down—onions, coffee, something that might have been meat—Karl and the others shouted insults through the hatch to hide the way their stomachs twisted.

“Save it for your officers!” one man called.

But their voices were thin, their bravado weaker than it sounded.

When the ship finally slid into an American harbor, the prisoners crowded to the scuffed railings. What they saw was not the chaotic, starving America they had been promised. Giant cranes moved cargo in steady arcs. Long lines of boxcars waited on tracks, engines puffing. Trucks rolled back and forth like beetles, everywhere at once.

The docks buzzed with activity, not desperation. Warehouses stretched for blocks. Smokestacks from nearby factories threw blue-gray columns into the sky. To men who had watched their own cities crumble into brick dust and rubble, this intact industrial landscape was jarring.

“God,” someone whispered. “Look at it.”

They were marched down gangplanks, through processing sheds that smelled of disinfectant and machine oil, and onto trains that seemed to go on forever. Through barred windows, Karl saw fields under snow, then small towns with intact roofs and gleaming shop windows, then more factories. Where Germany looked shredded and gray, this country looked annoyingly alive.

The laughter from the propaganda days had vanished. In its place was an uneasy silence.

They tried to hold on to one certainty: the food would surely reveal the truth. A strong nation might have railroads and skylines, but prisoners always met reality in the mess hall. The camp fences and watchtowers and shouted orders were familiar enough. Behind barbed wire, all systems looked alike.

Forty-eight hours after landing, Karl and roughly eight hundred other prisoners arrived at a camp in the American interior. Barbed wire, guard towers, neat rows of wooden barracks. A sign at the gate bore English words he couldn’t read. It might as well have said “End of illusions.”

The first meal came that evening.

They were marched into a long building where the air was thick with steam and the smell of food so rich it made their heads spin. Karl stepped through the doorway, expecting watery soup and a single slice of stale bread thrown on a table.

Instead, he saw trays lined up beside kitchen windows where men in white aprons ladled generous portions of stew thick with beans and meat into bowls. Next to the stew were baskets of fresh bread, real bread, soft and white inside. There were boiled potatoes. There were bowls of something green—cabbage, maybe, but cooked with care. On some plates, there was even gravy. Steam rose from everything.

The line moved forward. A guard motioned for Karl to take a tray. He did, hands almost numb. The American cook plopped a scoop of stew onto his plate.

“Next,” the man said, not unkindly.

Karl took a slice of bread. No one slapped his hand away. No one limited him to half a ladle. At the end of the line, another man poured coffee from a metal pot. The smell hit him like a memory from childhood: real coffee, dark and sharp. He stared, stunned.

“Move along,” someone behind him said.

He sat at the table. Around him, other prisoners had the same frozen look, like men who had stepped into the wrong film. For a few seconds no one moved.

Then someone took a bite.

The spell broke. They ate. Spoons scraped bowls. Bread disappeared. Coffee was drained to the last bitter drop. The conversation that followed was scattered and uneasy. A few muttered that the Americans were trying to fatten them up for some unknown purpose. Others joked weakly that they were being fed better in captivity than their families were in Germany.

Karl said nothing. He simply stared at his empty bowl. His body was beginning to remember what it felt like to be full.

The next morning, the pattern repeated.

They woke in bunks—actual beds with mattresses—inside barracks that were cold but dry. The breakfast line brought them bread with butter, oatmeal, sometimes scrambled eggs. The coffee was there again, hot and real. Lunch was stew or beans, sometimes meat. Dinner could be roast beef, pork, or chicken with potatoes. On Sundays they might even get a slice of pie or canned fruit that tasted absurdly sweet after years of ration sugar.

It wasn’t a feast every day. Sometimes the bread was stale, sometimes the stew thin. But it was always enough. Always reliable. Always there.

The shock was not that one meal had been generous. Anyone could stage a single show of abundance. The shock was that it continued, day after day, with the same regularity as the guards’ shift changes.

Somewhere in the system, someone had calculated how many calories a prisoner needed and ensured that those calories appeared on a plate three times a day. American medical officers noted the effects in their reports: prisoners gaining weight, recovering from malnutrition, their energy returning.

Karl saw it in the mirror, such as it was, in the polished metal of a canteen. His cheeks, once hollow, filled out. His belt, tightened to its last notch in France, now sat looser. His uniform hung differently.

Back home, his sister wrote from the Ruhr to say that rations had been cut again. She stood in line for bread that ran out before her turn. Meat came once a month, if at all. Coffee, she wrote, was “just a word now, not a drink.” She tried to keep the letter light, but between the lines, Karl read the same thing all German families were living: scarcity that bordered on desperation.

He did not tell her about the food in the camp. He wrote of the fences, the boredom, the ache of not knowing when or if he would see home. He skipped the coffee. He skipped the meat and the pie. The guilt was already heavy enough.

In the barracks, conversations shifted. A hard-line sergeant who still wore his Nazi Party pin insisted that this was proof of American decadence. “They waste food even on prisoners,” he scoffed. “They think they can buy our loyalty with fat.”

But others weren’t so sure. One man pointed out that American guards ate the same food as the prisoners, sometimes even less when supplies dipped. They all stood in line from the same pots.

“This isn’t charity,” another said quietly. “It’s just how they do things.”

At first, Karl tried to keep his old beliefs intact. He reminded himself that these were still enemies, that the same country feeding him had bombed his city flat. He thought of the propaganda reels, the slogans painted on the walls back home. He tried to square those images with the cook who sometimes slipped an extra ladle of stew onto his tray when he thought no one was looking or the guard who carried an older prisoner’s tray for him when his hands shook too badly.

Food had always been more than fuel in the war. It was a symbol. The Nazis had told their people that hardship forged character. They romanticized black bread, cabbage soup, coffee made from roasted grains. They sneered at the idea of white bread and sugar, calling them corrupting luxuries. In that worldview, abundance was weakness.

Yet here Karl sat, warm for the first time in weeks, with an American wool blanket over his shoulders and a full stomach, while his country starved. The Americans’ ability to feed him was not weakness. It was power—not the brutal power of a boot, but the quiet, unshakable power of plenty.

He began to look around the camp with different eyes.

The mess hall wasn’t a one-time illusion. It was part of a system that also included medical inspections, a camp canteen where he could purchase small items with his earned script, and rows of barracks that, while hardly luxurious, met a standard that astonished him. It wasn’t kindness for kindness’s sake. It was order. The Americans acted as if there were rules that applied even here, even to enemies.

Later, he learned the word for those rules: Geneva. Articles and conventions signed in distant years that said prisoners had rights to food, shelter, and medical care. Germany had signed them, too, but in Russia, he knew, German captives often starved to death. He had seen what his own army did to Soviet prisoners. Here, the guards corrected each other if anyone used unnecessary force. If a man hit a prisoner in anger, he could be disciplined.

Once, Karl saw a guard nudge a fellow with his elbow when the man barked too harshly at an old prisoner.

“Easy,” the first guard said under his breath. “We’re not them.”

It took a moment for Karl to realize who “them” meant.

Letters home continued to arrive. They told of winter 1946–47, of still smaller rations, of old people dying quietly in cold rooms. Karl’s mother wrote that she traded family heirlooms for sacks of potatoes. The bitterness in his throat had nothing to do with coffee.

Sometimes men argued in the barracks late at night. Some insisted they would return and rebuild a stronger, more just Germany. Others muttered that they wanted nothing more to do with politics or uniforms. A few clung to Hitler and the party like a lifeline.

“You’re forgetting who you are,” one die-hard said when a fellow prisoner defended the Americans.

“I’m trying to remember that I am human,” the other replied.

The food, the order, the routines didn’t turn them into Americans overnight. But they did something more subtle and more dangerous to any rigid ideology: they showed that everything they had been told about the enemy was incomplete, if not outright false.

The U.S. could afford to feed hundreds of thousands of prisoners these meals because, back home, its farms and factories poured out abundance. In 1944, American farmers produced more than 1.8 billion bushels of grain. Oil refineries, steel mills, and slaughterhouses roared all night. Unlike Germany, where every calorie and ton of coal was a struggle, America fought its war with full cupboards.

Karl learned, slowly, to admire that. Not the bombing, not the power that destroyed his city, but the confidence that could treat captives decently not out of charity, but because it simply could.

Years later, back in a rebuilt Germany, he would sit at a kitchen table with his own children and try to explain it.

“The strangest thing,” he would say, “was not that they beat us. It was that after they beat us, they fed us.”

Some of the men he’d sat beside at those mess tables never came back. A few stayed in America, working on farms or in factories once their POW status ended. Others returned home carrying memories that didn’t fit the new narratives of Cold War and victimhood. They talked quietly about bread and coffee, about fairness and rules. Some felt guilty; others saw it as a model for how a new Germany should treat its own weak.

The story of wartime abundance wouldn’t make the front page of history books. The big dates and battles would always get more ink. But among tens of thousands of former prisoners, the first American meal remained as vivid as any artillery barrage.

They had been taught that real strength meant enduring hunger and pain, that feeding soldiers well would soften them. In the end, they discovered the opposite. Strength, they realized, was having enough to take care of your own and still feed your enemy without fear that it would make you weaker.

The propaganda had called America soft.

Behind the barbed wire, spoon in hand, Karl knew better.

What he tasted wasn’t weakness. It was confidence—prosperity turned into policy, abundance turned into routine. A nation so sure of its power that it didn’t need to starve the men it had defeated.

For thousands of German prisoners of war, the real face of America was not a smiling cartoon soldier with a candy bar, but a real cook standing behind a steam-clouded counter, filling their plates without hesitation.

It was perhaps the most quietly revolutionary thing they experienced in that war: a reminder that winning is not only about how you fight, but about how you treat those you no longer have to fear.

News

(CH1) The German POWs Mocked America at First—Then They Saw Its Factories

When the train slid to a stop in Norfolk in January 1944, the men inside braced themselves for the worst….

(CH1) When German POWs Reached America It Was The Most Unusual Sight For Them

By the time the hatch slammed shut on the Liberty ship and the Atlantic swells began to lift the hull,…

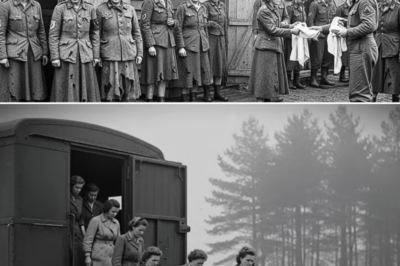

(CH1) “It Burns When You Touch It” – German Woman POW’s Hidden Injury Shocked the American Soldier

By the time the trucks pulled up to the gate at Camp Swift on May 12th, 1945, Texas heat had…

(CH1) Why Patton Was the Only General Ready for the Battle of the Bulge

On the night of December 19th, 1944, in a converted French army barracks at Verdun, the air in the conference…

(CH1) “He Gave Me His Blanket” — How a Frozen American Soldier Saved a Little Girl in the Ardennes

On the night of December 22nd, 1944, the Ardennes forest seemed to have turned entirely to ice. Snow swallowed the…

(CH1) German Women POWs Hadn’t Bathed in 6 Months — Americans Gave Them Fresh Uniforms and Hot Showers

On the morning of March 12th, 1945, the train rolled to a halt in a foggy corner of rural Georgia….

End of content

No more pages to load