By 1943, the Japanese Empire had carved its might into the black volcanic rock of New Britain and given it a name that carried the weight of a promise: Rabaul.

To Tokyo, Rabaul wasn’t just another overseas base. It was the Southern Shield, the anchor of their empire in the Southwest Pacific. The town nestled around a large, almost perfect natural harbor, ringed by smoking volcanoes and dense jungle. Japanese engineers arrived with blueprints and dynamite and began remaking the landscape.

They hollowed out the hillsides, drilling tunnels and carving bunkers deep into the volcanic rock. They poured concrete into the jungle and turned it into six airfields—wide strips of pale earth cut into the green. Zealous staff officers plotted circles of overlapping anti-aircraft fire on their maps and smiled. Heavy cruisers and destroyers packed the harbor, their hulls rocking gently in the water, smoke rising calmly from funnels as if they were at home rather than at war.

Then came the troops. Infantry. Artillery. Anti-aircraft gunners. Dock workers. Mechanics. By late 1943, over 100,000 Japanese soldiers and personnel were crammed into and around Rabaul, turning it into the most heavily fortified stronghold in the South Pacific. General Hitoshi Imamura, commanding the Eighth Area Army, called it “impregnable.” He meant it. From his headquarters, he could look at the map and see rings of defenses in every direction. Minefields. Shore batteries. Dense flak. Fighters on ready strips. Big guns on ships in the harbor.

He believed that volume alone—of concrete, of steel, of men—made Rabaul untouchable.

That belief would become his undoing.

He wasn’t content with garrisoning Rabaul; he overloaded it. At his insistence, the Imperial Navy and the Eleventh Air Fleet concentrated aircraft there: Mitsubishi A6M Zero fighters, G4M “Betty” bombers, D3A “Val” dive-bombers. They arrived faster than the ground crews could create dispersal bays. Hangars overflowed. The runways became parking lots. Wingtip nearly touched wingtip.

To Imamura and his staff, the sight was intoxicating: rows upon rows of aircraft, tail markings bright against the sky, all ready to rise as one. It was an image of overwhelming power, a steel fist drawn back to strike.

To an enemy pilot looking down from altitude, it was something else entirely.

American reconnaissance planes had been watching Rabaul for months. Flying high above the range of most anti-aircraft guns, they took photograph after photograph. Those images, when spread across light tables in Australian and American map rooms, told a clear story. The airfields were crowded to bursting, with almost no attempt at camouflage or dispersal. The harbor at Simpson and Keravia Bay was jammed with ships, anchored so close that their shadows overlapped in the aerial photos.

Rabaul, the fortress, had become Rabaul, the target.

On November 2nd, 1943, the spark arrived.

The Japanese had radar of a sort around Rabaul—equipment imported and improvised, undertrained crews huddled over glowing screens. It was crude. It worked when conditions were ideal. That day, conditions were not.

The first warning most of the pilots at Rabaul got was the sound.

A low, growing thunder of engines, dozens, then hundreds of them, rolling in from the sea.

Three hundred and forty-nine American aircraft appeared out of cloud and haze: waves of fighters and bombers from land bases in the Solomons. F4U Corsairs and F6F Hellcats swooped down, their machine guns and cannon chewing into parked aircraft. SBD Dauntlesses and TBF Avengers followed, torpedoes and bombs slung beneath their bellies.

On the airfields, pilots scrambled. Some ran toward their planes and were cut down by strafing runs before they could reach the ladders. Others managed to get into cockpits but were killed when the row of aircraft ahead of them exploded.

The Japanese planes were parked so densely that each bomb or strafing pass wasn’t just an isolated hit; it was a chain reaction. A single 500-pound bomb could shred five fighters at once. Burning fuel poured across the tarmac, licking at the next row of Zeros, turning them into torchs before anyone could drag them clear.

One pilot later remembered trying to start his engine as a wall of heat slammed into the cockpit. He looked up to see his neighbor’s aircraft erupt in flames and then his own instrument panel began to blister.

In ninety minutes, Rabaul’s vaunted air wing was gutted.

Smoldering wrecks dotted the runways. Hangars burned, collapsed, and burned some more. The air over the base was a chaos of smoke, tracer fire, and the black silhouettes of American planes arcing out to sea and back in again.

But it was only the beginning.

The American command understood that what they were seeing wasn’t just a successful raid but an opportunity. Rabaul’s defenders had concentrated their strength. Now that strength could be systematically destroyed.

On November 5th, the sky over Rabaul darkened again. This time the attacker was a task force of aircraft carriers, something the Japanese had not truly expected to see operating so close to their supposedly invincible bastion.

From the decks of USS Essex, Bunker Hill, and Independence, wave after wave of aircraft launched. More would follow on November 11th. Over 500 carrier-borne fighters, dive-bombers, and torpedo bombers took part in these raids.

For the commanders at Rabaul, it must have felt like a nightmare.

Their radar was overwhelmed, the scopes filled with blips. Sirens wailed. Anti-aircraft batteries opened up, filling the sky with black puffs and streaks of fire. Ships in the harbor lit off their own guns, gunners squinting into the smoke for any hint of silhouettes diving or gliding in.

It didn’t matter.

The sheer volume of the American assault outstripped anything the Japanese defenses could handle. Hellcats dove through flak to strafe ships at anchor, bullets tearing across decks and superstructures. Dauntlesses dropped bombs that walked down the length of a cruiser. Avengers dropped torpedoes that wove white wakes toward immobilized hulls.

The harbor became a cauldron.

Oil from ruptured tanks and bunkers spread quickly, forming slicks that caught fire and turned stretches of water into blazing carpets. Heavy cruisers—the pride of the Imperial Navy—reeled under impacts, superstructures shattered, decks afire.

A Japanese sailor who survived later wrote that the air “smelled of burning iron” and that “it felt like the island itself was screaming.”

In just over a week, Rabaul’s illusion of invincibility vanished. Hundreds of aircraft—many of them irreplaceable, along with the experienced pilots who flew them—were destroyed. Warships were sunk or so badly damaged that they had to flee, limping, to safer ports.

What was worse for Japan, perhaps, was not just what Rabaul lost but what it ceased to be. Without air cover, the harbor was a deathtrap. Without ships that could come and go freely, those 100,000 troops dug into bunkers and tunnels on the island were no longer a shield. They were a liability.

The Americans saw that too.

Given the choice between landing Marines on Rabaul’s beaches and bleeding for every cave and hill, or simply leaving the fortress alone to wither, they chose the second. They did not invade. They did not storm those volcanic ridges. They didn’t need to.

Instead, they bypassed Rabaul.

They severed shipping routes. They occupied islands north, south, and east of it. They turned the once-feared bastion into an accidental prison.

Inside the tunnels and bunkers, the Japanese soldiers waited with rifles and machine guns, expecting the thunder of landing craft and the shriek of rockets. Instead, they heard… nothing.

They became farmers instead of fighters, scratching sweet potato plots out of volcanic soil to supplement dwindling rations. Ammunition stocks sat untouched in magazines. Artillery guns rusted in place, their barrels never fired in anger again. Pilots who had survived the November raids found that there were no planes left for them to fly.

Occasionally, the quiet was shattered by the roar of engines and the whistle of bombs—because Rabaul became a convenient training ground. American and Allied air forces used it as a live-fire practice target, sending new squadrons to drop bombs on an enemy that could no longer strike back.

The fortress that had been meant to halt the Allied advance did nothing to stop it. The war moved on around Rabaul and then beyond it, leaving tens of thousands of men entombed in strategy and concrete.

When Australian troops finally entered Rabaul after Japan’s surrender in 1945, they didn’t have to fight their way in. They walked into a ghost city.

Japanese soldiers, thin but still in uniform, emerged from tunnels and bunkers and surrendered in orderly lines. Harbors were filled with rusted hulks and sunken masts. Airfields were graveyards of aircraft—Zeros and bombers left where they had burned or parked, their frames now choked with vines.

General Imamura’s proud bastion had not been conquered in a climactic battle.

It had been rendered irrelevant.

His mistake had not been in building strong defenses; it had been in assuming that massed strength in one place equaled security. By turning Rabaul into a static, heavily loaded fortress without the means to maneuver or be effectively supplied once the seas and skies were lost, he had unwittingly built a tomb.

Today, if you walk through the jungles around Rabaul, you can still find relics. A Zero’s fuselage half-swallowed by roots. A canopy frame rusting under ferns. Concrete revetments sinking into the soil. These are not the marks of a fortress that did its job, but of a place where war’s logic turned in on itself.

One hundred thousand men, trapped behind their own walls.

A fortress without freedom of movement, without sustainable support, without the ability to influence the broader war, is no fortress at all.

It is just a cage.

News

(CH1) Japanese Admirals Thought The US Navy Was Crippled — Until 6 Months Later At Midway.

TOKYO — DECEMBER 8, 1941 The air in the Imperial Japanese Navy headquarters is thick with cigarette smoke and triumph….

(Ch1) THE P-51’S SECRET: HOW PACKARD ENGINEERS AMERICANIZED BRITAIN’S MERLIN ENGINE

DETROIT, MICHIGAN — AUGUST 2, 1941 Two engines roared to life on test stands inside Packard’s East Grand Boulevard plant….

(Ch1) The Calutron Secret: How WWII Engineers Used 14,700 Tons of Treasury Silver for Uranium Separation

Story title: The Silver That Split the Atom 1. “We Need 6,000 Tons” August 3, 1942 Washington, D.C. – U.S….

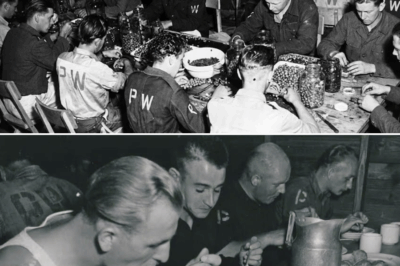

(CH1) German POW shocked: US camp guards did THIS on Christmas Eve

Story title: The Gift Beyond the Wire 1. The Scar December 24, 1943 Camp Hearne, Texas The barbed wire sang…

They Told Him American POW Camps Were Hell. When the Dining Hall Doors Opened, He Froze

Story title: The Tables Were Set 1. Tunisia, 1943 – The End of One Future On the night Joseph Huber…

Inside the N@zi Prison Where Inmates Became Democracy’s Fiercest Defenders

Story title: The Law Above Orders 1. The Last Case Bavaria, May 7th, 1945 The coffee was what unnerved him….

End of content

No more pages to load