The guard had seen men cry before—on battlefields, in hospital tents, in letters silently folded and unfolded again. But this was different.

“They’re crying over pads,” he muttered, baffled.

It was May 19th, 1945, at Camp Hearne, Texas. The war in Europe was over, but its wreckage was still arriving by the truckload.

A small convoy idled on the red gravel. The air shimmered with heat and dust. From the open backs of the trucks stepped thirty-three women in faded Luftwaffe gray. Not combat troops. Not SS. Nurses, clerks, radio operators—Helferinnen of the German armed forces, now prisoners of war, shipped across the Atlantic from a continent in ruins.

They moved slowly, boots sinking slightly into the powdery Texas dirt. Their faces looked carved out of fatigue. In Germany, they had slept in cellars, schoolhouses, and barracks that always smelled of damp wool and coal smoke. Here, the air smelled of diesel, sun-baked wood—and faintly, impossibly, of coffee.

The camp gates opened with a scrape and clank.

An American nurse, lieutenant’s bars on her shoulder, stood waiting with a clipboard. Her name was Dorothy. Her hair was pinned up neatly under her cap, and her voice, when she called them by number, was brisk but not harsh.

“You’ll be issued soap, toothpaste, and personal supplies,” she said through the interpreter.

The first German woman stepped forward. Dorothy opened a wooden crate at her feet and pulled out a neat stack of white sanitary pads. Cotton. Clean. Soft. Wrapped in tissue.

The woman stared.

“Einmalig,” the interpreter said quietly. “Single use.”

The word seemed to hang in the hot air.

Single use.

The women looked at one another, trying to process what they’d heard. For years, they had lived in a completely different reality. They had cut and re-cut old rags, boiled them in dented buckets, traded scraps of linen like currency. Cotton was rationed to the last thread, diverted to bandages and ammunition. Sanitary pads, if they existed at all, were something you heard about in half-whispered rumors from before the war.

Now an enemy nurse was handing them away.

“After you use it, you throw it out,” the interpreter explained.

A brittle, disbelieving laugh escaped one of the women. Another raised a hand to her mouth, as if to hide shock or shame. A few simply began to cry—quietly, without drama, tears slipping down cheeks already lined by fear and hunger.

The guard shifted his weight, uncomfortable. “They’re crying over pads,” he repeated, as if saying it again would make it make sense.

The interpreter watched the women’s faces and shook her head.

“No,” she said softly. “They’re realizing what they lost.”

The Myth of Plenty

Back in 1943, the posters had shown something very different.

Blonde nurses with perfect hair, crisp aprons, smiles firm and clean. Captions declared, “Die deutsche Frau – stark im Dienst!” The German woman—strong in duty. Ministry of Propaganda newsreels showed them marching in neat rows, tending to wounded soldiers with shining stainless steel instruments in spotless wards.

They had believed those images, because they had nothing else.

When shortages began, it was never a failure. It was always sacrifice. Soap disappeared from shelves? Use less. Cotton rationed? Reuse more. The state did not admit deprivation; it recast it as virtue. Hardship meant loyalty.

By 1942, the Reich’s textile reserves were gone. Cotton from Egypt and the Middle East had been cut off by the British blockade. Cellulose—the same plant material that made sanitary pads possible—was urgently needed for gunpowder, shell casings, and field dressings. Factories that once produced civilian goods now produced war.

In that economy, the female body simply slipped down the priority list.

By 1944, many German women had stopped expecting comfort of any kind. Rags served as pads. Wall insulation became toilet paper. Old uniforms were cut into pieces and re-cut until they fell apart in the wash. In field hospitals, nurses quietly treated infections they knew came from dirty improvised cloth—but there was little they could do.

And yet, the radio voice in Berlin kept repeating: “Our women want for nothing. Their needs are the Reich’s priority.” The lie held as long as there was no comparison.

Then came capture.

The Empire of Everyday Things

Across the ocean, the American home front was living through a different kind of war.

Yes, there were ration books. Yes, there were posters urging conservation. But the American industrial base was enormous, protected from bombing and supplied by vast farms and oil fields. In 1944 alone, the United States produced over 5 million tons of paper pulp—more than four times Germany’s depleted output. Companies like Kimberly-Clark developed “cellucotton,” a highly absorbent cellulose originally used for bandages, and quickly adapted for sanitary pads.

By the mid-1940s, American factories were turning out billions of disposable pads a year.

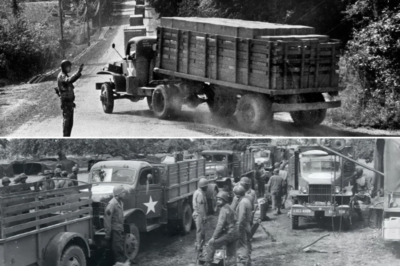

On the U.S. War Production Board’s charts, these were just units: tons, bales, cases. On Navy shipping schedules, they were just cargo—another box on another manifest bound for an overseas base, a field hospital, or a POW camp.

At Camp Hearne, they arrived in crates. The same supply system that fed American troops in Europe could feed and equip their prisoners in Texas with scarcely a strain.

To the Americans, these boxes were routine.

To women like Clara Eisen and her comrades, they felt like science fiction.

“We Thought We Were the Modern Ones”

In the barracks that evening, the white pads lay on blankets and bunks like alien artifacts.

The American nurses had already moved on to the next task—vaccinations, bed assignments, medical checks. They didn’t hover or explain further. To them, a pad was just another item on the inventory sheet. For the German women, it became a mirror held up to their own vanished world.

“We used to cut up old undershirts for this,” one woman said, fingertips barely touching the cotton.

“And now they tell us these are to be thrown away,” another muttered. The idea itself felt obscene.

Someone tried to laugh. The sound cracked and died.

In the corner, Clara turned the pad over in her hands.

“We thought we were the modern ones,” she said quietly. “They told us we were.”

They fell into silence again.

Outside the barracks, American life rolled on. Mess hall loudspeakers played swing records between announcements. Trucks backed up to storage sheds, tailgates banging open. Crates of Coca-Cola and tins of coffee clinked as they were stacked. Soap. Toothpaste. Cigarettes. Pads. All moving according to schedules, requisitions, and warehouse counts.

Inside, the German women lay awake, pads tucked under pillows or folded carefully into their kit bags like relics, staring at the dark rafters.

What they were feeling wasn’t just surprise. It was a kind of grief.

Not for the lost Reich.

For the realization that the civilization they had been taught to revere had never been capable of this simple, effortless decency.

The Arithmetic of Comfort

In the months that followed, the contrast only sharpened.

Camp records tell the story in numbers:

A German civilian in 1945 survived on roughly 1,200 calories a day—less in the worst-hit cities.

A German office worker might have had no soap at all unless she traded for it on the black market.

In Texas, a German POW—male or female—received about 3,200 calories a day. Three meals. Meat several times a week. Bread that wasn’t stretched with sawdust or potato flour.

Camp Hearne issued roughly half a ton of soap a week to about 1,200 prisoners. More in a month than some German communities saw in a year.

Those figures weren’t designed to humiliate anyone. They were simply the output of a system that worked.

American quartermasters didn’t sit around saying, “Let’s show off.” They said, “We have 1,200 PS this week. Issue standard hygiene. Check Geneva Convention compliance.” The pads and soap were not propaganda. They were policy.

And that was precisely what made them devastating.

The women of the Reich had been promised that their state was absolute, disciplined, unstoppable. That hardship was a mark of righteousness. That sacrifice was proof of superiority.

Now, defeating them was an enemy that could produce enough for everyone—including its prisoners—without ceremony.

Abundance wasn’t weakness. It was strength in its most quiet form.

“I did not change sides,” Clara would later write in her diary. “I changed understanding.”

Going Home to Ruins

By late 1945, the repatriation lists started going up.

Names. Numbers. Dates. Columns posted on bulletin boards under the Texas sun. German prisoners—men and women—gathered in front of them, scanning quickly.

Clara’s name eventually appeared.

The ship out of Galveston was clean, organized, and well-provisioned. Each bunk had a blanket and a small hygiene kit: soap, toothbrush, a few pads wrapped in thin paper. Three hot meals a day. Coffee at breakfast. It felt almost indecent.

On deck at night, she stared into the black gulf water and thought about what waited on the other side.

Germany did not meet her with warehouses and swing music.

Bremerhaven’s port smelled of damp ash and rotting timbers. Gutted buildings hunched over the quays. Lines of tired people in patched coats waited for a ladle of soup. There were no crates of soap being casually unloaded here, no Red Cross nurses handing out hygiene kits to everyone.

The care packages would come later—American, British, Swedish. For now, there was just emptiness.

She found a space in a half-collapsed schoolhouse, sharing the floor with other women who cut curtains and old bedsheets into rag bandages by candlelight. One of them, a former nurse from Essen, asked Clara what it had been like “over there.”

“They gave us too much,” Clara said at last. “I mean—not too much food, but too much proof that we had been wrong.”

The other woman laughed without humor. “Too much comfort can feel like an accusation,” she said.

She wasn’t wrong.

What the Pads Really Meant

Years later, historians would trace the shipments, compare production figures, and write articles about pulp capacity and industrial output. Economists would talk about the Marshall Plan, about GDP curves and currency reform.

But if you ask the women who saw both worlds, they almost never talk about graphs.

They talk about small things.

About soap.

About bread.

About the first time an Allied camp nurse gave them a pad and told them it was for one use only.

For Clara, that pad became a symbol she couldn’t shake.

In 1946, when CARE packages began arriving in Germany, she recognized the shape of the cardboard boxes immediately. Inside: coffee, sugar, powdered milk, canned meat—and sometimes, tucked in a corner, another stack of sanitary supplies.

The American habit of comfort had followed her home.

She kept one pad from Texas for years, folded flat between diary pages. When she later married and had daughters, she would sometimes take it out and show them.

“This,” she would say, “is a piece of the war you will never read about in schoolbooks. Your father talks about tanks. Politicians talk about treaties. But this is how I really understood that we had lost.”

Not just because the Reich fell.

But because its enemy had learned how to mass-produce dignity.

Civilizations aren’t measured only by what they can destroy. They’re measured by what they can easily spare.

For the women of Camp Hearne, that truth didn’t come from a speech or a courtroom. It came from a crate on a dusty parade ground in Texas, from the astonished tears over something as humble as a pad, from the quiet realization that there is a kind of power that doesn’t need to shout, or terrorize, or even prove itself.

It just hands you a small, soft, disposable thing and says, “Of course you need this. Everyone does.”

And in that moment, you finally understand who really won.

News

(CH1) When Luftwaffe Aces First Faced the P-51 Mustang

On the morning of January 11th, 1944, the sky over central Germany looked like it was being erased. From his…

(CH1) German Pilots Laughed at the P-51 Mustangs, Until It Shot Down 5,000 German Planes

By the time the second engine died, the sky looked like it was tearing apart. The B-17 bucked and shuddered…

(CH1) October 14, 1943: The Day German Pilots Saw 1,000 American Bombers — And Knew They’d Lost

The sky above central Germany looked like broken glass. Oberleutnant Naunt Heinz had seen plenty of contrails in three years…

(CH1) German Generals Laughed At U.S. Logistics, Until The Red Ball Express Fueled Patton’s Blitz

The first thing Generaloberst Alfred Jodl noticed was that the numbers, for once, were comforting. For weeks now, the war…

(CH1) German Teen Walks 200 Miles for Help — What He Carried Shocked the Americans

The first thing Klaus Müller remembered about that October afternoon was the sound. Not the siren—that had been screaming for…

(CH1) German Child Soldiers Couldn’t Believe Americans Spared Their Lives and Treated Them Nicely

May 12, 1945 – Kreuzberg, Berlin The panzerfaust was heavier than it looked in the training pamphlet. Fifteen-year-old Klaus Becker…

End of content

No more pages to load