WESTERN GERMANY — APRIL 1945

They told her the Americans would cut off her hand.

Not might. Not maybe. They spoke with the certainty that fear gives people when they’ve run out of anything else to hold on to.

In the back of a prisoner truck rattling along a muddy road, Helga Weiss cradled her ruined hand against her chest as if she could keep it attached by force of will alone.

The injury was three days old—crushed when a supply truck overturned during the retreat. The swelling had turned ugly. The skin was darkening. The smell of infection had begun to bloom through the torn cloth she’d wrapped around it, a sickly sweetness that made the other women shift away without meaning to.

An older prisoner leaned close, voice low, eyes hard with the wisdom of terror.

“When the Americans see that,” she whispered, “they won’t waste medicine on a German. They’ll take a saw and remove it. That’s what they do.”

Helga was twenty-three. A telegraph operator—one of thousands of young women who had served the Wehrmacht in auxiliary roles while Germany burned around them.

Now she was a prisoner. Wounded. Starving. Heading toward an enemy she had been trained to fear more than death itself.

The propaganda had always been clear:

Americans were savages.

They tortured prisoners.

They let the wounded rot.

They enjoyed cruelty.

Helga believed it—because belief was safer than uncertainty, because questioning meant loneliness, and loneliness in wartime felt like death.

But four hours after arriving at an American field hospital, Helga would lie on an operating table with tears streaming down her face… watching an enemy surgeon work with steady hands to save every single one of her fingers.

They would not share a language.

Yet what happened in that room would dismantle everything she thought she knew about the world.

CHAPTER I — THE ROAD TO CAPTIVITY

The truck stopped on a scarred stretch of countryside that no longer looked like a place people lived.

Farmhouses stood like broken teeth against a gray sky. Fields were cratered where crops should have been. Smoke hung in the air, mixed with diesel fumes from American vehicles that now owned the road.

Helga pressed her shoulder against the wooden slats of the truck bed and tried to make herself smaller than fear.

Her hand throbbed with every heartbeat. Not sharp pain anymore—deeper than that. A sick, pulsing ache that had swallowed her entire body.

She hadn’t eaten in two days. Hadn’t slept in any way that counted. The world had become a blur of engines, orders, and the grinding anticipation of whatever came next.

Around her sat thirty other German women—secretaries, telephone operators, nurses—uniforms torn, faces hollow, eyes stripped of youth.

A girl with blond braids whispered into the silence:

“Where are they taking us?”

Another woman, older, answered without looking up.

“Does it matter? We go where they tell us.”

The truck lurched forward again and Helga bit her lip hard enough to taste blood as the movement sent fresh lightning through her hand.

She thought of her mother in Hamburg—if Hamburg still existed. The last letter Helga had received spoke of infernos, neighborhoods turned to ash, tens of thousands dead in a single night.

She didn’t know if her mother was alive.

She didn’t know if she herself would be by sunset.

When the truck stopped again—this time for good—an American soldier lowered the tailgate and shouted something in English.

The prisoners didn’t understand the words, but the meaning was clear enough.

Move. Now.

They climbed down one by one.

Helga tried last.

Her legs folded beneath her the moment her boots touched the mud.

She would have fallen face-first if a strong hand hadn’t caught her arm.

She looked up into the face of a young American soldier—red hair, freckles across his nose, eyes tired but alert.

He said something she didn’t understand.

Then his gaze dropped to her bandaged hand.

His expression changed immediately.

“Medic!” he shouted over his shoulder.

Helga’s heart began to pound.

This is it, she thought.

They’ve seen it.

Now they’ll cut it off.

She tried to pull away, weak and shaking.

“No,” she whispered in German. “Please. No.”

But the soldier held her steady—not cruelly, not roughly. Just firm, as if her body was an object he refused to let fall.

The world swam.

Then the medic arrived, and Helga’s fear became a physical thing in her throat.

CHAPTER II — THE SCHOOL THAT BECAME A HOSPITAL

They carried her into a building that had once been a German school.

Now it was an American field hospital.

The hallways that once smelled of chalk and childhood now smelled of antiseptic and blood. The sounds had changed too: groans, shouted orders, metal carts clattering over cracked tiles.

Helga lay on a stretcher, staring at ceiling stains as American soldiers moved her past rows of wounded men.

Most were Americans.

But not all.

She saw a German uniform on one bed—bandaged chest rising and falling. Next to him, an American lay with his leg in a cast.

No separate ward.

No punishment corner.

No “enemy” section.

Just bodies. Just wounds. Just the same harsh truth written into skin.

They’re treating Germans, Helga realized.

The thought hit her like nausea.

That can’t be right. It must be a trick.

An American nurse appeared—hair in a tight bun, hands efficient, face calm.

She smiled and spoke in English.

Helga couldn’t answer.

The nurse didn’t care. She simply patted Helga’s shoulder and began unwrapping the cloth around her hand.

What lay beneath was worse than Helga had allowed herself to imagine.

Her fingers were swollen grotesquely, skin tight and discolored in purple-black gradients. The smell of infection rose like a wave.

The nurse’s smile faltered for half a second.

Then she called out sharply.

More voices. More footsteps. A doctor’s shadow fell across Helga.

Someone shook their head.

They’re deciding how much to remove, Helga thought.

Her tears came hot and unstoppable.

She closed her eyes and waited for the end.

But the end didn’t come.

Instead, the stretcher moved again—down another corridor, into a smaller room with brighter lights and metal trays lined with instruments.

The sight of surgical tools made her breath hitch.

“Please,” she begged in German. “Please don’t cut it off. I need my hand. I… I work with my hands…”

Her words fell into the air like stones.

Then a man appeared at her side—tall, maybe in his forties, graying at the temples, face carved with exhaustion.

A surgeon.

An enemy surgeon.

His assistant slid gloves over his hands.

He looked down at Helga—not unkind, not angry. Serious. Focused.

He spoke in English, slow and measured, and Helga—despite not understanding a word—felt something strange:

Not cruelty.

Not contempt.

Concern.

The nurse gestured at Helga’s tears.

The surgeon nodded once.

Then he called for someone else.

A moment later, another figure stepped into view.

A man in a German uniform.

Helga stared, confused.

He was young—thirty, perhaps—with wire-rim glasses and an intelligent face. His left arm rested in a sling.

“I am Corporal Werner Hoffman,” he said in German. “A prisoner like you. I translate.”

Helga grabbed onto him with her eyes, desperate.

“They’re going to cut it off,” she whispered. “Tell them no. Tell them I would rather die.”

Werner shook his head slowly.

“They are not going to cut off your hand,” he said.

Helga blinked.

“What?”

Werner glanced at the surgeon, then back to Helga.

“This is Captain James Morrison. He says he wants to try to save it.”

Helga could not process the word.

Save.

“But it’s infected,” she whispered. “It’s… it’s black.”

“Yes,” Werner said, voice careful. “The infection is severe. It may fail. There is risk. But he wants to try.”

Helga stared at the American surgeon bent over her hand as if calculating a war inside it.

“Why?” she asked. “Why would he do this? I am… the enemy.”

Werner translated.

Captain Morrison looked up and met Helga’s eyes for the first time.

He spoke slowly so Werner could keep up.

Werner’s translation landed like a blow:

“He says you are not his enemy. You are his patient.”

Helga’s throat tightened.

“He says he took an oath. To heal anyone who needs healing.”

Werner hesitated, then continued.

“He says… ‘Your hand does not know what country it belongs to. It only knows it is injured.’”

Helga had heard speeches about honor and duty for years.

She had never heard anything like this.

“Tell him…” Her voice broke. “Tell him I am grateful. I don’t understand. But I am grateful.”

Werner translated.

Morrison nodded once—almost like a soldier acknowledging another soldier.

Then he turned back to her hand.

And the work began.

CHAPTER III — FOUR HOURS

Time does strange things in an operating room.

It stops being minutes and becomes breaths.

Helga was given an injection that softened the edges of reality, but she did not sleep. She couldn’t.

She watched through heavy eyelids as Captain Morrison worked on her hand with the patience of a watchmaker.

He cut away dead tissue with small scissors.

He irrigated infected pockets until fluid ran dark.

He tested each finger for life—pressing, waiting, judging.

Twice, his assistant suggested amputation.

Twice, Morrison shook his head.

Werner stayed in the room, translating only when necessary.

Mostly there was silence—broken by the clink of instruments, the murmur of medical instructions, the steady rhythm of someone refusing to surrender.

Halfway through, Morrison paused and flexed his hands.

Helga saw the fatigue in his face.

He’d already done surgeries that day.

Twelve hours on his feet.

An assistant offered him coffee and gestured at the door—take a break.

Morrison shook his head, took one sip, and returned to the table.

Helga whispered to Werner, “What did he say?”

Werner listened, then translated with disbelief:

“He said he can’t leave now. Your hand has started to respond. If he stops, the progress will be lost.”

Helga turned her face away so no one would see her crying.

This made no sense.

She had been taught Americans were monsters.

Monsters did not do this.

Monsters did not fight for the finger of an enemy.

Then Morrison leaned over her worst finger—her index. The infection there was stubborn, aggressive, determined.

For a terrifying moment, Helga thought this was where he’d give up.

Instead, he called for more instruments. More medicine.

He fought for that finger like it was a battlefield and he was refusing to retreat.

Thirty minutes.

Then another.

Finally, at four hours and seventeen minutes, Morrison stepped back.

He spoke, voice rough with exhaustion.

Werner translated:

“He says he has done everything he can. The infection was severe. But if you follow recovery instructions, you will keep your hand. All five fingers.”

Helga broke.

Not a quiet tear. Not a dignified sob.

She cried like a child—great heaving sounds that shook her whole body.

She tried to speak, but gratitude has no language when your world has been turned upside down.

Captain Morrison watched her for a moment.

Then, with the gentleness of someone who had seen too much suffering to ever add to it, he patted her shoulder.

He murmured something soft in English.

Werner didn’t translate.

He didn’t need to.

Helga understood anyway.

Then Morrison left the room to go do it again for someone else.

CHAPTER IV — CHOCOLATE

Recovery was slow.

Helga woke in a long ward with clean sheets and a pillow that smelled faintly of soap. Luxury, after weeks of trucks and rubble.

American nurses checked her bandages. Administered medicine. Smiled.

One nurse—young, with bright red curls and freckles—began practicing German phrases.

“Guten Morgen,” she said each morning, accent terrible, smile genuine.

Helga did not know how to answer How are you today?

Her hand throbbed. The medicine made her dizzy. But something deeper ached: the collapse of certainty.

Everything she’d been taught was wrong.

The Americans weren’t devils.

They were people.

They laughed.

They complained.

They wrote letters home.

The food was better than anything Helga had eaten in years.

Soft bread. Real meat. Vegetables.

Then, one day, the nurse placed a small square in Helga’s palm.

Chocolate.

Helga stared at it as if it were gold.

She hadn’t tasted chocolate since before the war. She had almost forgotten what sweetness was.

The nurse mimed eating.

“Good,” she said.

Helga put it on her tongue and closed her eyes.

Sweetness flooded her mouth and tears came immediately—because the taste carried memory, and memory hurt.

“Why?” Helga whispered in German, though the nurse couldn’t understand.

Why do you give this to me?

Do you not know what my country did?

The nurse only patted her arm and moved on.

Helga began to understand: this wasn’t forgiveness.

This was something stranger.

It was the refusal to become what the war demanded.

CHAPTER V — THE HAND COMES BACK

Three weeks later, Captain Morrison removed her bandages for good.

Helga stared at the gauze as it fell away and braced for horror.

But what emerged was… her hand.

Scarred. Weak. Still swollen.

But whole.

All five fingers, pink and alive, moving when commanded.

“Make a fist,” Werner translated. “Slowly.”

Helga concentrated.

Her fingers curled inward—stiff, reluctant—but they curled.

A loose fist. Then open again.

Pain, yes.

But possible.

Werner translated Morrison’s words:

“It will take time. But the function is there. You will use your hand again.”

Helga stared at her fingers, then at the man who had fought for them.

The last wall inside her—built from propaganda and fear—collapsed without drama.

Just… collapsed.

That night she wrote in her diary:

They told me the Americans would cut off my hand.

Instead, a man I had never met spent four hours saving it.

If the enemy is not evil, then what was all of this for?

She had no answers.

Only the certainty that hate no longer fit in her body.

CHAPTER VI — “GOOD”

The day Germany surrendered, the hospital didn’t change much.

No more incoming wounded. No more frantic triage. Just the slow work of healing and waiting.

Someone played music on a radio that night. Nurses offered small cups of wine even to German prisoners.

“To peace,” the red-haired nurse said, smiling through exhaustion.

Later, Captain Morrison came to Helga’s bedside.

He didn’t celebrate. His face was shadowed in a way that spoke of everything he’d had to do.

He sat. Quiet.

No translator.

Finally, he took Helga’s healing hand gently in both of his, checked her fingers the way he always did, then looked up and nodded once.

“Good,” he said.

One word.

But Helga understood the full sentence beneath it:

You survived.

You kept it.

You still have a future.

“Thank you,” she said in broken English. “Thank you… for my hand.”

Morrison paused at the door when he left, speaking slowly.

Helga didn’t catch every word—but she caught enough:

Hands can destroy.

Hands can build.

You choose which kind of hands you want to have.

Then he was gone.

EPILOGUE

Helga left the hospital for a POW camp with a diary, a few letters, and a hand she could still feel.

She returned to a Germany of rubble and hunger.

But she carried something invisible too:

The knowledge that propaganda can lie about enemies—

and that mercy, when it appears, can crack a worldview wider than any bomb.

Whether she became a teacher, a translator, a mother—whatever life she built—she made herself one promise:

I will use this hand to build something.

And whatever I build, it will not be built on hate.

News

(Ch1) Japanese Women POWs Arrived On American Soil —And Were Shocked To See How Advanced The US Really Was

They Were Brought to America as Prisoners. What They Discovered There Broke an Empire Without Firing a Shot. Oakland, California…

(Ch1) Japanese POW Women Hid Their Pregnant Friend in Terror — U.S. Doctors Promised to Protect the Child

They Hid Her in the Dark. What the Americans Did Next Terrified Them More Than Any Weapon. WISCONSIN, 1945 —…

(CH1) “He Took a Bullet for Me!” — Japanese POW Woman WATCHED in Horror as Her American Guard Saved Her

THE LIE SHE CARRIED ACROSS THE OCEAN Akiko Tanaka arrived in the Arizona desert already condemned—at least in her own…

(CH1) “Don’t Touch Her, She’s Dying!” — Japanese POW Women Shielded Their Friend Until the U.S. Medics

SAN FRANCISCO HARBOR — WINTER 1945 Sachiko’s hand was on Hana’s shoulder the way it had been for weeks—steady pressure,…

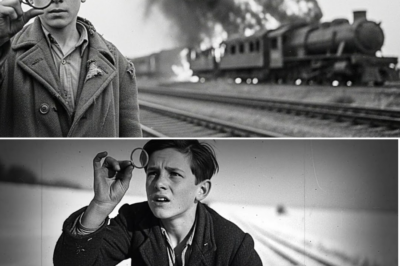

(Ch1) The 12-Year-Old Boy Who Destroyed Nazi Trains Using Only an Eyeglass Lens and the Sun

THE WINTER LENS Occupied Poland, 1943 A boy crouches behind a snow-covered embankment. He is twelve—maybe thirteen—thin the way hunger…

(Ch1) How One Commander’s “Matchstick” Trick Made 4 Wildcats Destroy Zeros They Couldn’t Outfly

This Trick Did Not Win a Dogfight; It Stopped the Funerals How one exhausted commander, two matchsticks, and a heretical…

End of content

No more pages to load